The United Postal SERVICE—The One Word that Makes all the Difference

Letter Carrier Dwight Washington was recently delivering mail in an Abington, PA, neighborhood when he spotted a house on fire. Washington leapt into action, rushing to pound on the front door and also alert neighbors, who called 911. The Postal Service employee located a fire extinguisher and a garden hose, and he battled the blaze while the home’s occupants—who had been asleep—escaped to safety. . . . Abington Fire Marshal John Rohrer later mailed a letter to the local Post Office. “Had the fire gone unchecked for a few more minutes, the outcome could have been devastating,” Rohrer wrote. “Due to Mr. Washington’s quick, responsible actions, the fire was contained, the residents were saved from harm and the home was deemed to be inhabitable, restoring some normalcy to the family’s life.”[1]

Introduction

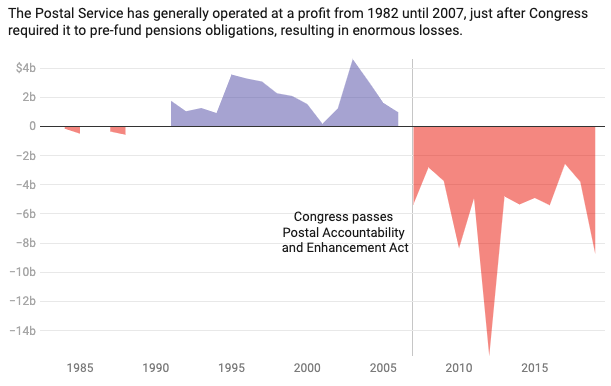

The United States Postal Service (USPS) is the most widely lauded government service, with a 91% approval rating among the general public.[2] The USPS has also been ranked as the most efficient and trusted postal service in the world.[3] It is not surprising that USPS enjoys such a high rating—Americans depend on it for a host of essential services including food, medicine, paying bills, shopping, and running small businesses.[4] The USPS is an important part of America’s health care framework, often delivering life-saving medicine to customers.[5] Rural Americans, in particular, who often lack adequate digital infrastructures, depend on the USPS as a “lifeline.”[6] However, despite its continued importance for Americans, several recent developments have created financial challenges for the USPS. Since the postal reforms of the 1970s, the USPS has depended on revenue from its own operations.[7] The rise of e-commerce and the decline of first-class mail has led to a stagnation of USPS revenues since 2000.[8] The USPS has run deficits since 2009 and is currently $160.9 billion in debt.[9] The USPS has largely weathered these challenges by cutting its workforce and moving to last-mile package delivery for large retailers as well as by making other adjustments to its model.[10] Despite hostile comments by President Trump who views the USPS as a “joke,”[11] and the view in some quarters of the business press that the USPS has a broken model, the vast majority of the problems at the USPS are wholly political, caused by privatization politics and bad Congressional legislation in 2006 that required the USPS to fully pre-fund employee benefit obligations decades into the future—an onerous obligation rarely borne by any public or private entity.[12] This manufactured budget crisis is being used as an excuse to make radical changes at the USPS that are unnecessary, deeply unpopular, antidemocratic, and harmful for Americans.

This essay makes the case that privatization is not the best solution to the problems at the USPS, which were largely created by bad legislation. The USPS’s service-oriented assignment means that the organization’s goals are very different from the typical profit-maximization model of the business corporation. Part I of this essay documents the historical mission of the USPS, showing the roots of its public service mission. In Part II, we contrast this critical, service-oriented mission of the USPS with the increasing move towards privatization and with it, the imposition of a purely business logic: to create and maximize profits for its shareholders. Finally, in Part III, we talk about the specific dangers that applying a purely business rationale on this important organization will have on Americans in general.

The debates that are currently circulating in the popular discourse regarding making the USPS more “profitable” and “efficient” typically overlook its public mandate. Privatization advocates make a fundamentally faulty assumption in attempting to model the USPS after a private corporation that must turn a profit. A business corporation’s decisions are justified on the grounds of their ultimate benefit to shareholders, even if those benefits come at a cost to other stakeholders such as employees, vendors, customers, and the surrounding community. In fact, one of the hallmarks of the “successful” publicly-traded corporation is one that consistently meets analysts’ profit-making projections, quarter after quarter.[13] In contrast, the USPS has a Universal Service Obligation (USO) which requires it to serve all Americans regardless of whether it is profitable to do so.[14] Its service-oriented mission is also specifically focused on other outside stakeholders: its workers, its customers, and the larger community. With the rise of mail-in voting, the USPS is likely to remain a crucial piece of infrastructure for American democracy for the foreseeable future.[15] Trying to have the USPS fulfill this mission while also imposing a profit-maximization strategy on the organization is folly.

I. Mission Critical: The USPS’s Roots in Public Service

The USPS is a government entity with a mandate to serve the whole public, called its Universal Service Obligation (USO). [16] As the former Postmaster General Megan J. Brennan stated: “The men and women of the United States Postal Service provide an essential public service and bind the nation together as a part of the country’s critical infrastructure.”[17] The Postal Service has a very explicit mission:

to provide the nation with reliable, affordable, universal mail service. The basic functions of the Postal Service were established in 39 U.S.C. § 101(a): “. . . to bind the Nation together through the personal, educational, literary, and business correspondence of the people. It [the Postal Service] shall provide prompt, reliable, and efficient services to patrons in all areas and shall render postal services to all communities.”[18]

In order to effectuate its mission, the USPS has undertaken many duties in a way that underscores its utility as a public good. In 2010, the Urban Institute,[19] a Washington D.C. think tank, prepared a report for the Postal Regulatory Commission entitled A Framework for Considering the Social Value of the Postal Services.[20] In it, they identified eight categories of social good that the USPS provides, in accordance with its mandate: (1) consumer benefits (by establishing baseline rates for delivery services); (2) business benefits (including providing delivery support for rural businesses); (3) safety and security benefits (including acting as a neighborhood watch for the community); (4) environmental benefits (including “providing an opportunity for first and last mile delivery on behalf of other companies, thereby reducing neighborhood traffic”); (5) supporting other federal and state services (such as mail-in voting); (6) supporting knowledge circulation (by distributing newspapers and journals); (7) relationship building (both by facilitating social connection and being a focal point in rural communities); and, (8) community and national pride and identity.[21]

Within the context of the study, much of the social value has inured for the benefit of the larger community: including small and large businesses, elder members of the community, its employees, and other community-based stakeholders.[22] Indeed, some of the benefits identified by the study are solely within the domain of a public function that cannot be mimicked by a similar for-profit business. For instance, a long-standing USPS policy is for carriers to “keep watch on elderly citizens and respond heroically in emergency situations.”[23] In addition, carriers often serve in a “neighborhood watch” capacity, reporting potential crimes or emergencies by calling 911,[24] or (as noted in the introduction) they may even help assist in exigent situations. Finally, the Post Office itself serves as a central hub for many civic activities and community life. Although the Post Office’s role with mail-in ballots is dominating the popular discourse right now, the USPS also provides other direct-service functions to the community, including: passport services; military registration; federal tax forms; and coordination with the Census Bureau.[25] In fact, for-profit businesses in the same industry such as the United Parcel Service (UPS) have deliberately contracted with the Postal Service to increase the for-profit’s revenues—specifically because these businesses are unwilling to go where the USPS is mandated to deliver. Under a program called the “last-mile” initiative, delivery services like FedEx and UPS hand off many of the packages that are scheduled to be delivered to more rural areas to the USPS for that final doorstep delivery.[26]

The roots of many of these services date back to the country’s birth. The power to establish and regulate a postal service is one of the few powers of Congress that is specified in the Constitution.[27] The framers of the U.S. Constitution considered a postal service pivotal to the nation’s democratic infrastructure.[28] As the U.S. Supreme Court has stated, USPS served “a vital yet largely unappreciated role in the development of” the United States.[29] The USPS expanded throughout the nineteenth century, adding universal delivery in American cities and for rural areas by the late nineteenth century. The USPS further expanded during the New Deal and by mid-century was handling a huge volume of deliveries.[30] The 1960s was a tumultuous decade for the USPS, whose New Deal infrastructure was badly straining under the weight of a booming postwar economy.[31] Postal workers were egregiously underpaid in an era of rising wages and were having troubles paying the bills in expensive cities.[32] A series of disruptive strikes paralyzed the postal system when workers demanded higher wages and better working conditions. The USPS was reorganized in 1970 during the Nixon Administration after a wildcat strike over wages. As a result, it became a self-funding public agency through the Postal Reorganization Act of 1970.[33] Although, beginning with the e-commerce era, USPS began to face a steep decline in first-class mail volume, it still largely operated in the black despite these challenges.[34]

Starting in the early 2000s, postal privatization moved onto the political agenda. Libertarian think tanks have long promoted postal privatization on ideological grounds.[35] At the same time, logistics and delivery companies have wanted to break up the USPS to get a larger piece of the package delivery market.[36] They eventually found sympathetic ears in the first George W. Bush Administration.[37] Soon after George W. Bush took office, he created a commission to study postal reform, which issued a United States Postal Service Transformation Plan.[38] The Plan took aim at the postal unions, which it believed were driving up costs and had too much bargaining power, and called for downsizing the USPS workforce and proposed other “efficiency” measures.[39] Soon thereafter, it was revealed that USPS had been overfunding its pension payments.[40] When Congress realized that it could offload some of its own veteran benefits obligations onto the USPS it passed a law in 2003 that “shifted the costs of postal employees’ military service-related pension costs from the U.S. Treasury to the USPS—a $27 billion obligation.”[41] In other words, Congress moved billions of dollars of pension obligations that had accrued to veterans from the Department of the Treasury (where they would represent red ink on the federal budget) to the USPS (where they would not). This had several effects. As Philip Rubio points out, the law “(1) made the USPS (instead of the Treasury Department) responsible for postal military veterans benefits; (2) forced the USPS to use its pension savings to pay off a Treasury loan; and (3) required the USPS to tell Congress how it would use its future savings. In other words, Congress was using the USPS to subsidize its balanced budget.”[42]

The next major development came three years later when Congress enacted the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act[43] (PAEA), which made several important changes to the budgeting and operations of the USPS. First, it removed the $27 billion veterans’ pension obligation that it had imposed in 2003.[44] Second, in apparent furtherance of its privatization agenda, it divided USPS products into “competitive” and “market dominant” categories.[45] The reason for this was the belief that USPS was using revenue from its market dominant services (e.g., first-class mail) to subsidize its competitive services (e.g., package delivery), thus placing delivery and logistics companies at a disadvantage.[46] PAEA placed price caps on the market dominant products to prevent USPS from using that revenue to lower prices for its competitive services.[47] It is this price cap that President Trump has complained about in his war with Jeff Bezos, The Washington Post, and Amazon.[48] Obviously, if USPS raises rates on its package deliveries, consumers and large retailers will shift to other delivery services, which would further starve the USPS of revenue and help make privatization the only reasonable alternative. Third, PAEA required the USPS to shift from a pay-as-you-go model for funding pensions to a pre-funding model.[49] Under the PAEA, the USPS was required within ten years to pay billions into a fund to offset present and future pension commitments, an onerous obligation for any entity.[50] The pre-funding requirement loads the USPS with a large debt, placing it in an ongoing and wholly manufactured budget crisis. Although PAEA may not have been consciously designed to privatize the USPS in the short term, it has had the effect of accelerating an otherwise avoidable crisis: “The PAEA’s basic intent more strongly suggests a Bush administration desire to (1) relieve its financial responsibility for owing money to the USPS for pension overcharges; and (2) effectively force the downsizing of the USPS, which the presidential commission and the postmaster general were already in agreement about.”[51] As the table below[52] shows, The PAEA pre-funding mandate is responsible for an astounding 92% of the USPS losses between 2007 and 2018.[53] The pandemic has only led to a further decline in first-class business mail, the dissemination of COVID-19 in the USPS workforce, and significant turnover.[54] This has all of the hallmarks of a failing business structure, making calls for privatization sound reasonable—if the Postal Service was your typical for-profit endeavor. However, as the next section will demonstrate, the privatization/profit-maximization model cannot and should not apply to one of our oldest agencies.

Source: The Conversation, supra note 52.

II. Of Privatization and Profit-Making

The privatization framework is another step along the continuum of increased corporate influence in traditionally social spaces. Privatization is one side of that coin—with its outsourcing of public goods and utilities to a private entity. However, when a public good does transition from the public to the private sector, the other side of the coin comes into full display: the usurpation of social goods for shareholder profit. While for-profit businesses certainly have their place, as this section demonstrates, the use of this model for public utilities will prioritize different values in a way that was never intended for USPS.

A. Privatization: A Short History

Conservative think tanks had been arguing for privatization since the 1970s, but privatization became a serious policy issue in the Reagan era, when politicians were seeking to shrink the size of government.[55] Advocates of privatization tout a number of benefits of outsourcing government services to the private sector: increased competitiveness, lower costs, efficiency and a smaller government footprint.[56] Where privatization does work, the services are often targeted and relatively small in geographic scope (e.g., trash collection).[57] Advocates of democratically managed public infrastructures have pointed to the dangers of allowing for-profit firms to own or manage important public goods.[58] Critics cite potential for corruption, loss of control and increasing inequality when private companies control important public infrastructures.[59] Although advocates claim that privatization is simply a neutral way of providing goods and services, critics explain that choosing a public or private provider is not a neutral choice.[60] When private-sector firms take charge of a government service, that can lead to feedback loops where the private firm seeks to influence the shape of the policies being administered.[61] Also, outsourcing government functions may obtain cost savings by replacing good jobs with part-time or insecure employment.[62] Others have been concerned about ensuring accountability in an era of “government by contract.”[63] In the 2000s, cities and states began to experiment with privatization of large infrastructures such as roads, with mixed success.[64] Largescale privatization initiatives like those proposed for USPS remain controversial and are likely to remain so for the foreseeable future, as Americans worry that privatization of public goods may not be aligned with the interests of Americans in universal and equitable public services.

B. Profits: The True Purpose of the Corporation

One of the hallmarks of a business corporation is to secure profits for its shareholders. Indeed, this concept is embedded in both case law[65] and statute.[66] While different states have provided their own perspective on what this means—witness for instance, Delaware’s discussion of the Business Judgment Rule[67]—it remains true that a corporate board’s action is ultimately justified from the standpoint of shareholder profit.[68] Indeed, the rise of alternative models of corporate formation serve as a testament to the enduring rule. For instance, benefit corporation statutes, which permit for-profit corporations to consider additional stakeholders other than shareholders, are now present in 37 state statutes.[69] Moreover, the rise of the B-Corp labeling project,[70] which requires member corporations to report on the triple bottom line,[71] shows the enduring resistance to the traditional point at hand.

The famous (or infamous) statement by the Michigan Supreme Court in Dodge v. Ford that “[a] business corporation is organized and carried on primarily for the profit of the stockholders. The powers of the directors are to be employed for that end”[72] quickly established shareholder primacy as the dominant paradigm in corporate governance jurisprudence. This, in turn, has led to significant debates regarding whether the shareholder model should be the framework that is used for businesses.[73] However, whether we like it or not, that is the predominant model at play today. Even when scholars have pushed back against the shareholder primacy model, most have recognized that it is the governing legal framework.[74] Indeed, the reality of corporate litigation reveals that lawsuits against corporations are typically brought as either claims for state law violations of the duty of care,[75] the duty of loyalty[76] or bad faith;[77] or federal law claims regarding a corporations fraudulent reporting on their reports filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission. However, in each instance, (with the exception of the rare cases brought by the SEC) the claims are brought by shareholders, asserting—in essence— that the corporation’s actions have led to a loss of profits for the corporation and as such, a loss of benefit to the shareholder.[78]

The rise of constituency statutes in many jurisdictions is also a reflection of many states’ understandings regarding just how powerful the shareholder primacy paradigm is. As one of us has discussed in an earlier piece:

Many state codes have recognized [the shareholder should not be given exclusive consideration] in their enactment of constituency statutes that expressly allow for corporate boards to consider other interests than those of shareholders . . . . Delaware has no constituency statute. Case law in Delaware, however, has made clear that in all instances, except when the life of the corporation is ending, directors have the rights (but not the duty) to consider other interests besides the shareholders.[79]

Not only has the traditional profit-making enterprise been the dominant narrative in corporate law, it has also been presumed in popular culture. Milton Friedman, in a famous article, affirmed the jurisprudential overtones of Dodge v. Ford by declaring:

[I]n a free‐enterprise, private‐property system, a corporate executive is an employe[e] of the owners of the business. He has direct responsibility to his employers. That responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with their desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society . . . .”[80]

In previous generations, corporations defended their actions both in court and in the court of public opinion on these grounds, declaring that their duties were to their shareholders. As such, in the name of shareholder profit maximization, corporations took great leeway to make their businesses profitable.

That may very well be changing.

In January 2019, Larry Fink (the CEO of BlackRock, one of the largest institutional investors in the world holding almost $7 trillion in assets[81]) declared that corporations should perhaps exist for reasons other than pure profit-making.[82] He decried the single-minded pursuit of this traditional corporate agenda and discussed ways in which corporate CEOs could also benefit society.[83] His take was viewed by some as another gambit of increasing the profits of his own corporation;[84] it could also be seen as the latest step in the current trend of corporations (assisted by civil society and international organizations) examining their increasing societal impact.[85]

But, in the end, BlackRock is still a business and is governed by its own corporate jurisprudence, which, at best, typically ranks stakeholders other than shareholders as a distant second. Indeed, even the business judgment rule, which provides substantial leeway to corporate officers and directors in how they manage the affairs of the company, still starts from the presumption that a business makes decisions for the end of benefiting the corporation’s bottom line. Whether the corporation frames that as a long-term benefit or a short-term gain, most corporations do frame it from that standpoint (in fact, most commentators would argue that the reason why Henry Ford got into trouble with the courts in the infamous Dodge v. Ford case is because he explicitly rebuked the shareholder-centered rhetoric). Which means that if Larry Fink, tomorrow, decides that in a post-pandemic world he needs to make the “hard choices” and lay off workers or cut their salaries or invest in companies that are more profitable—if less socially conscious—he can do so without legal ramifications. A shareholder cannot bring suit to say that Fink breached his duty of care, duty of loyalty, or obligation of good faith by focusing solely on profit maximization.

The profit-maximization effect is profound. When one is working under a model that must support the best interests of investors’ money, many of the decisions that are made by the corporation will be done from this perspective. Even more exacerbating is when a corporation initiates an initial public offering and becomes a publicly traded corporation; whether governed by case law or short-termism,[86] corporate executives begin to think of their decisions primarily from the vantage point of how this will affect the daily price of a stock when it is received in the market (whether or not the market will really be impacted by these decisions is another question entirely).[87] Many a corporate fraud began because an executive felt pressure to meet analysts’ expectations regarding its value—which then led that executive to engage in accounting or other shenanigans to make sure those numbers fit.[88] This could happen less so in non-publicly traded corporations because, in theory, they could frame this within the longer-term profit goals of their shareholders,[89] but it is still done from the standpoint of corporate shareholders.

To wit: here are some of the things that businesses have done in the name of shareholder profit: cut workers’ salary; laid off workers;[90] reduced fixed costs;[91] moved its business out of a community, devastating that community;[92] engaged in corporate fraud;[93] and engaged in harmful environmental impacts.[94]

Now, imagine for a moment if USPS was under an obligation to undertake these initiatives in the same way as for-profit corporations would do it. Many of the services that we now take for granted would likely be eradicated. And, as the next section demonstrates, this move towards privatization may finally be taking hold.

III. The War to Privatize USPS

To compound the problems created by PAEA, the USPS has again been targeted by politicians with a larger agenda to radically scale back the USPS and put it on a path to privatization—a campaign that was renewed when Donald Trump took office. President Trump has made no secret of his disdain for the USPS, which he has called “a joke” among other hostile public statements.[95] He has claimed many times his belief that USPS is offering Amazon a sweetheart deal and that Americans are getting “scam[med].”[96] He has stated that he would hold up any COVID-19 relief package that included a bailout for the USPS.[97] Earlier this year, Trump appointed Louis DeJoy, a former logistics executive (who had not previously worked for the Postal Service in his career), to Postmaster General.[98] In addition, DeJoy is now under investigation by Congress for possible fraud and conflicts of interest.[99] DeJoy immediately began what many believe to be a major overhaul and scaling back of USPS, dismantling hundreds of processing machines and instituting a policy designed to speed up deliveries at the cost of leaving packages behind in processing centers.[100] Worse still, recent operational changes at the USPS made by Postmaster General Louis DeJoy called into question the viability of mail-in voting this November, which President Trump has made no secret he opposes on partisan grounds. USPS is also being sued by a number of states who seek to undo the changes already made and prevent further changes to USPS before the November election.[101] A federal judge recently issued a nationwide injunction against DeJoy’s restructuring efforts, which he called “an intentional effort on the part of the current Administration to disrupt and challenge the legitimacy of upcoming local, state, and federal elections . . . .”[102] This is precisely the sort of corruption that critics of privatization are worried about.

President Trump’s Task Force on the United States Postal System issued a report in 2018 arguing that USPS is on an “unsustainable path” and floating the idea, among other measures, of a full or partial privatization of the USPS.[103] When President Trump reiterated the postal privatization plan in 2018, he misleadingly stated that “many European nations” have switched to private postal services, when in reality only a handful have.[104] Given its larger privatization agenda, unsurprisingly the Task Force Report does not mention the congressional pre-funding mandate as the source of the current troubles. The report, full of business jargon like “value proposition” and “business objective,” states that the USPS is “less relevant to citizens and businesses due to the emergence of virtually free digital alternatives that deliver information instantly and more directly to the recipient,”[105] proposes to significantly privatize the USPS, and speaks favorably of other countries’ privatized postal services in comparison with the USPS’s public monopoly. The Report also claims that mail delivery to “sparsely populated areas” have caused “the USPS’s financial instability,” which suggests that privatizers view the universal public nature of mail service as a problem in need of correction.[106] The report proposes a scaling back of USPS package deliveries to allow private providers to move into that market while leaving the difficult and unprofitable services to the USPS.[107]

The Report further argues that the USPS service model has become irrelevant and that it should no longer be granted monopoly status. This is so, the report argues, because of new communication technologies that have reduced the demand for USPS first-class mail delivery.[108] Instead, the USPS should “correct market failures,” that is, it should deliver to difficult and unprofitable locations that private companies will not want to handle. As the Report explains:

[D]ue to the rise in e-commerce, the USPS’s package business increasingly competes with a robust and growing network of national, regional, and local delivery companies. To respond to these changes and return the USPS to financial stability, the USPS must adopt a new, more targeted business model that is based on providing essential mail and package services for which there is no cost effective, nationwide, private sector substitute.[109]

In other words, the USPS should continue to provide “essential services” but otherwise mail and package delivery should be left to private logistics companies.[110] This fits in with the general strategy of privatization to disaggregate and monetize public infrastructures, choosing which parts of it are easier to manage and thus more profitable while leaving the difficult cases (like rural delivery) to be handled by government.[111] The Report is essentially making the case that the days when mail delivery can be considered a public good are behind us.

The Report makes a faulty and misleading assumption when it claims that the primary source of the budgetary issues currently facing the USPS is the result of the decline in first-class mail. This is simply not the case: while the USPS has faced a steep decline in first-class mail, it has largely made up for that decline with last-mile package delivery.[112] Moreover, the Report cites the USPS balance sheet, which shows $89 billion in liabilities versus $27 billion in assets, to create the impression that the USPS is on an “unsustainable path.”[113] However, the Report neglects to mention that the largest single item on the liability side—$42B—represents the pre-funding mandate that Congress imposed in 2006.[114] When read in light of the pre-funding requirement, which Congress has proposed to rescind, the current financial situation at the USPS is not as dire as the Report makes out.[115] Moreover, even with the pre-funding mandate, 87% of USPS pension obligations are funded.[116] The PAEA hobbled the USPS’s finances and reduced its ability to invest in capital upgrades (e.g., new, larger delivery vehicles designed for packages rather than letters) and otherwise make the changes that it needs to make to adapt to the e-commerce era.[117] Thus, it is not surprising that the finances of the USPS look a lot worse than they would otherwise look without the pre-funding obligation. The answer for some, including Donald Trump, is privatization.[118] However, it is privatization politics that have wreaked havoc on the USPS in the first place.[119]

It is simply not feasible for a private company to recreate the extensive delivery and service infrastructure of USPS.[120] Selling off USPS to a private company would mean cuts to services and deliveries, especially in rural regions, as the private company focused on smaller and more targeted service areas. Moreover, privatization of the USPS would be deeply anti-democratic in both form and substance. Now that postal privatization is squarely before the public, it is turning out to be thoroughly unpopular. Like other largescale privatization plans in recent years (for example, Social Security), there has been little support for privatization of this popular public agency.[121] Polls early in the COVID-19 pandemic showed that large majorities of Americans favored Congressional action to repair the problems at the USPS.[122] Media coverage of Trump’s war against the USPS has been overwhelmingly negative.[123] Moreover, many see the slowdowns and cutbacks that Postmaster General Louis DeJoy imposed on USPS as part of an attempt to undermine vote-by-mail this November, a strategy that President Trump believed would help his re-election chances.[124] Calls to privatize the USPS are based more on partisanship, ideology, and the interests of the private logistics industry than they are on sound public-facing policy. Privatization would likely lead to closures and cost-cutting that would erode the quality and increase the price of these essential services for rural Americans.[125] President Trump’s Task Force Report underscores this fact. As Misdiagnosis: A Review of the Report of the White House Task Force on the Postal Service notes:

The [Report’s] principle recommendations would dramatically raise mailing costs for “commercial mailers” and shippers, slash the frequency and quality of delivery, and gut the standard of living of postal employees by outsourcing their jobs, stripping them of collective bargaining rights and reducing their retirement and workers’ compensation benefits. These recommendations would weaken, not strengthen the Postal Service—and threaten the most efficient and affordable universal postal system in the world.[126]

Moreover, it is unclear what benefit Americans would gain through privatization that doesn’t already exist with UPS, FedEx, and other private logistics companies that deliver documents and packages. Although some smaller countries have moved to private models for mail delivery, the sheer geographical size of the United States makes such a model untenable here.[127] Large retailers have come to rely on the USPS’s “last-mile” infrastructure which deliver packages from sorting centers to residences. Since the Report’s privatization plan would raise the prices on package delivery, it is no surprise that Amazon and other large retailers oppose the plan.[128]

Now, imagine for a moment, if USPS was under an obligation to undertake these initiatives in the same way as for-profit corporations would do it. Among the things that would probably be changed are:

- Cuts in worker’s salaries (result of the strike and union efforts)

- Massive layoffs

- Deleting all of the purely service-oriented services (like checking in on the elderly or calling in emergencies).

The USO would need to be seriously scaled back, as is already happening, because the truth of the matter is that universal delivery is not profitable. Yet, it’s essential—especially for people living in rural communities. We would suddenly have to justify all of the services that the USPS does as part of its job within the context of shareholder engagement. So, universal service? How profitable is that? Get rid of it! That program that allows carriers to check on people who are home alone? What does that have to do with the bottom line? It’s gone! Suddenly, any community-initiated activity that USPS will have done must be viewed exclusively or primarily from the standpoint of making a profit. Is that really what we want for our Postal Service?

Conclusion

One of the ironies of this targeting of the USPS to become more business-like is that it is coming at a time when many CEOs of for-profit businesses are explicitly trying to move away from a framework that focuses on a corporation’s shareholders. As such, the Postmaster General is showing just how out of step he is with the prevailing winds of change. Indeed, rather than privatizing the USPS, we should be re-investing in the venerable service’s public mandate. Rural Americans in particular rely on USPS for a variety of critical services.[129] The USPS is a key piece of public infrastructure for commerce and public health.[130] 40 million people don’t have access to broadband internet[131] and rely on USPS to pay bills and participate in commerce. Why should we start from austerity and belt-tightening? Why not expand the USPS and shift its model to broaden its public service mandate? For example, why not allow the USPS to expand into postal banking (which it used to do),[132] broadband, and other services that Americans need?[133] This would help poor Americans particularly (the unbanked, living paycheck to paycheck) who rely on payday lenders for short-term liquidity.[134] Also, the USPS currently employs nearly 500,000 Americans in good-paying jobs with pensions and health care.[135] Given that economists are forecasting a long-term economic downturn due to COVID-19, it makes little sense to gut an agency with one of the largest number of employees of any government agency. Do we want government to shed employees or turn more jobs into part-time or even gig economy positions?[136] Instead of privatizing, we should be thinking about how to make the USPS stronger, more stable, and more durable for the long term. The real question is: how can our critical public infrastructure, built up over a century, better serve the American people?

- .Rick Owen, Postal Employee Saves Sleeping Customers’ Lives, Postal Emp. Network (May 10, 2019), https://postalemployeenetwork.com/news/2019/05/postal-employee-saves-sleeping-customers-lives/ [https://perma.cc/V4DN-3KFU]. ↑

- .Public Holds Broadly Favorable Views of Many Federal Agencies, Including CDC and HHS, Pew Res. Ctr. (Apr. 9, 2020), https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/04/09/public-holds-broadly-favorable-views-of-many-federal-agencies-including-cdc-and-hhs/ [https://perma.cc/Y3XL-8NTP]. ↑

- .Press Release, U.S. Postal Serv., United States Postal Service Ranked No. 1 in the World (Feb. 6, 2012) (available at https://about.usps.com/news/national-releases/2012/pr12_023.htm) (“USPS earned the premier ranking due to its high operating efficiency and public trust in its performance.”). ↑

- .Jim McKean, U.S. Postal Service: An Essential Service, USPS Blog: Postal Posts (May 1, 2020), https://uspsblog.com/essential-postal-workers/ [https://perma.cc/AQK5-RJEL]. ↑

- .Susan Cantrell, The USPS Is a Vital Part of Our Health Care System, The Hill (Aug. 24, 2020, 12:30 PM), https://thehill.com/opinion/healthcare/513360-the-usps-is-a-vital-part-of-our-health-care-system [https://perma.cc/7VT9-A25J] (“The postal service has become a vital part of the U.S. health care system. Disruptions to the U.S. Mail will create barriers to health care access for those who depend on the Postal Service for their medications.”); Phil McCausland & Geoff Bennett, Postal Service Delays of Prescription Drugs Put Thousands of American Lives at Risk, NBC News (Aug. 23, 2020, 5:00 AM), https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2020-election/postal-service-delays-prescription-drugs-put-thousands-american-lives-risk-n1237756 [https://perma.cc/UY8E-S9ZL]. ↑

- .Catherine Kim, If the U.S. Postal Service Fails, Rural America Will Suffer the Most, Vox (Apr. 16, 2020, 8:20 AM), https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/4/16/21219067/us-postal-service-shutting-down-rural-america-native-communities [https://perma.cc/MB8H-9DBU]; Sheridan Hendrix, He Delivers Where Amazon and FedEx Won’t: USPS Worker Covers ‘The Last Mile’ to Rural America, USA Today (Aug. 18, 2020, 10:37 AM), https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2020/08/18/usps-rural-americans-depend-mail-carriers-medical-items/3382677001/ [https://perma.cc/5ZEL-Z6ZY]. ↑

- .Tyler Powell & David Wessell, How is the U.S. Postal Service Governed and Funded?, Brookings Inst.: Up Front (August 26, 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/08/26/how-is-the-u-s-postal-service-governed-and-funded/ [https://perma.cc/8R85-GKQQ]. ↑

- .See Drew DeSilver & Katherine Schaeffer, The State of the U.S. Postal Service in 8 Charts, Pew Res. Ctr. (May 14, 2020), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/14/the-state-of-the-u-s-postal-service-in-8-charts/ [https://perma.cc/2D6D-6H5A]. ↑

- .Id.; Jacob Bogage, The Postal Service Needs a Bailout. Congress is Partly to Blame, Wash. Post (Apr. 15, 2020, 5:00 AM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/15/postal-service-bailout-congress/ [https://perma.cc/82NR-E3EL]. ↑

- .See Jacob Bogage & Josh Dawsey, Postal Service to Review Package Delivery Fees as Trump Influence Grows, Wash. Post (May 14, 2020, 12:35 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/05/14/trump-postal-service-package-rates/ [https://perma.cc/G56W-EUT7]. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Sarah Anderson, Scott Klinger & Brian Wakamo, How Congress Manufactured a Postal Crisis—And How to Fix It, Inst. Pol’y Stud. (July 15, 2019), https://ips-dc.org/how-congress-manufactured-a-postal-crisis-and-how-to-fix-it/ [https://perma.cc/WKY4-Z4FM]. ↑

- .This general sense of the corporation as a profit-only machine is slowly changing. See, e.g., CVS Caremark to Stop Selling Tobacco at all CVS/pharmacy Locations, CVS Health (Feb. 5, 2014), https://cvshealth.com/newsroom/press-releases/cvs-caremark-stop-selling-tobacco-all-cvspharmacy-locations [https://perma.cc/5SME-QAEL] (discussing the pharmacy chain’s decision to stop selling tobacco, despite a projected $2 billion loss in revenue). However, it is still, by far, the predominant narrative used by corporations to justify their actions. ↑

- .U.S. Postal Serv., Report on Universal Postal Service and the Postal Monopoly 2 (2008). ↑

- .Sam Berger & Stephanie Wylie, Trump’s War on the Postal Service Hurts All Americans, Ctr. for Am. Progress (Aug. 19, 2020, 9:02 AM), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/democracy/news/2020/08/19/489664/trumps-war-postal-service-hurts-americans/ [https://perma.cc/GL2J-D8H4]; Ray Brescia, The USPS Is a Crucial Tool for Democracy—Helping the Left and the Right Organize, Wash. Post (Aug. 17, 2020, 5:00 AM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/08/17/usps-is-crucial-tool-democracy-helping-left-right-organize/ [https://perma.cc/2FMT-KMYT] (“Attacking the Postal Service is an attack on democracy itself—something the Founders understood. They recognized the significance of the Postal Service, understanding a functioning and safe means of communication was central to democracy, and as we are learning in a pandemic, it remains just as essential now.”). ↑

- .See generally Off. Inspector Gen., U.S. Postal Serv., No. RARC-WP-15-001, Guiding Principles for a New Universal Service Obligation (2014). ↑

- .Megan J. Brennan, Postmaster General Statement on U.S. Postal Service Stimulus Needs, USPS: About (Apr. 10, 2020), https://about.usps.com/newsroom/statements/041020-pmg-statement-on-usps-stimulus-needs.htm [https://perma.cc/4R4M-2PC5]. ↑

- .Chapter 1: Our Mission, USPS: About, https://about.usps.com/strategic-planning/cs09/CSPO_09_002.htm#:~:text=The%20Postal%20Service’s%20mission%20is,business%20correspondence%20of%20the%20people [https://perma.cc/Q8GP-MYRG]. ↑

- .The Urban Institute describes itself as a “nonpartisan [think tank that] publishes studies, reports, and books on timely topics worthy of public consideration.” Nancy Pindus, Rachel Brash, Kaitlin Franks, & Elaine Morley, A Framework for Considering the Social Value of Postal Services, Urban Inst., i (2010), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/28656/412097-a-framework-for-considering-the-social-value-of-postal-services.pdf [hereinafter Urban Inst.]. ↑

- .See generally id. ↑

- .Id. at iii–iv. ↑

- .See Barnali Choudhury, Aligning Corporate and Community Interests: From Abominable to Symbiotic, 2014 BYU L. Rev. 257, 264–65 (2014) (discussing the importance of corporate-community relationships and the differences between it and other corporate-stakeholder relationships). ↑

- .U.S. Postal Serv., 2009 Annual Report: The Challenge to Deliver 11 (2009); see Urban Inst., supra note 19, at 13. ↑

- .Urban Inst., supra note 19, at 13. ↑

- .Id. at 17. ↑

- .Id. at 9. ↑

- .U.S. Const. art. 1, § 8, cl. 7. See generally Richard R. John, Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (1995) (providing general historical background on the USPS). ↑

- .For an account of the early history of the postal service and its importance to democracy and development, see Casey Cep, We Can’t Afford to Lose the Postal Service, New Yorker (May 2, 2020), https://www.newyorker.com/news/annals-of-communications/we-cant-afford-to-lose-the-postal-service [https://perma.cc/AFT6-NWX4]. ↑

- .U.S. Postal Serv. v. Council of Greenburgh Civic Ass’ns, 453 U.S. 114, 121 (1981). ↑

- .U.S. Postal Serv., The United States Postal Service: An American History 38 (2020). ↑

- .Id. at 60–63. ↑

- .APWU History, Am. Postal Workers Union, https://apwu.org/apwu-history [https://perma.cc/EEK4-2W52]. ↑

- .Philip F. Rubio, Undelivered: From the Great Postal Strike of 1970 to the Manufactured Crisis of the U.S. Postal Service 119–46 (2020). ↑

- .Pieces of Mail Handled, Number of Post Offices, Income, and Expenses Since 1789, USPS: About (Feb. 2020), https://about.usps.com/who-we-are/postal-history/pieces-of-mail-since-1789.htm [https://perma.cc/JJZ7-CYS9]. ↑

- .See, e.g., James Bernard, Cato Inst., Policy Analysis No. 47, The Last Dinosaur: The U.S. Postal Service (1985); Chris Edwards, Privatizing the U.S. Postal Service, Cato Inst. (Apr. 1, 2016), https://www.cato.org/publications/tax-budget-bulletin/privatizing-us-postal-service [https://perma.cc/T7YP-CTKD]; Lisa Rein, Think Tank to Study Privatizing Most Postal Service Operations, Wash. Post (Jan. 3, 2013), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/think-tank-to-study-privatizing-most-postal-service-operations/2013/01/03/2adc0b08-55ed-11e2-8b9e-dd8773594efc_story.html?hpid=z5 [https://perma.cc/3L2Z-SD6A]. ↑

- .See Rubio, supra note 33, at 185; Joseph Piette, Who’s Pushing Post Office Privatization?, Workers World (Aug. 11, 2013), https://www.workers.org/2013/08/10387/ [https://perma.cc/3GEL-CD2L]. ↑

- .Rubio, supra note 33, at 185. ↑

- .U.S. Postal Serv., Transformation Plan (2002). ↑

- .Rubio, supra note 33, at 186 (“The attitude of the Bush administration and the USPS toward downsizing postal services largely paved the way for the 2009 postal financial crisis.”). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Kevin R. Kosar, Cong. Research Serv., The Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act: Overview and Issues for Congress 1 (2009). ↑

- .Rubio, supra note 33, at 187. ↑

- .Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act of 2006, Pub. L. No. 109-435, 120 Stat. 3198. ↑

- .Kosar, supra note 41, at 2. ↑

- .Id. at 3. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 3 (“Under PAEA, the USPS may raise the rates (prices) of products in the market-dominant class by no more than the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). Prices of products in the competitive class must be based on market-type factors, such as ‘costs attributable,’ which Section 202 of the statute defines as ‘the direct and indirect postal costs attributable to such products through reliably identified causal relationships.’”). ↑

- .Bethany Biron, Trump Reignites Feud with Amazon over USPS Financial Woes—But the Relationship Between the Ecommerce Giant and Government Agency is Far More Complicated, Business Insider (Aug. 17, 2020, 3:37 PM), https://www.businessinsider.com/trump-reignites-campaign-against-the-us-postal-service-and-amazon-2020-8 [https://perma.cc/W27K-SFWK]; Damian Paletta & Josh Dawsey, Trump Personally Pushed Postmaster General to Double Rates on Amazon, Other Firms, Wash. Post (May 18, 2018, 12:32 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/trump-personally-pushed-postmaster-general-to-double-rates-on-amazon-other-firms/2018/05/18/2b6438d2-5931-11e8-858f-12becb4d6067_story.html [https://perma.cc/3A4Y-WCAT]; Jim Tankersley, Trump Said Amazon Was Scamming the Post Office. His Administration Disagrees, N.Y. Times (Dec. 4, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/04/us/politics/trump-amazon-post-office.html [https://perma.cc/86WX-6CHT]. ↑

- .Kosar, supra note 41, at 2–3. ↑

- .Jeff Spross, How George Bush Broke the Post Office, The Week (Apr. 16, 2018), https://theweek.com/articles/767184/how-george-bush-broke-post-office [https://perma.cc/H3Q3-29LZ]. ↑

- .Rubio, supra note 33, at 190. ↑

- .Jena Martin & Matthew Titolo, Mail Delays, the Election and the Future of the US Postal Service: 5 Questions Answered, Conversation (Oct. 22, 2020, 8:26 AM), https://theconversation.com/mail-delays-the-election-and-the-future-of-the-us-postal-service-5-questions-answered-148214 [https://perma.cc/YS6H-2J74] [hereinafter The Conversation]. Table data from USPS: About, supra note 34. ↑

- .Nat’l Ass’n Letter Carriers, Misdiagnosis: A Review of the Report of the White House Task Force on the Postal Service 2 (2019). ↑

- .Jacob Bogage, Postal Service Memos Detail ‘Difficult’ Changes, Including Slower Mail Delivery, Wash. Post (July 14, 2020, 12:47 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/07/14/postal-service-trump-dejoy-delay-mail/ [https://perma.cc/36H9-3KA5] (discussing how the pandemic has led to a decline in first-class mail); Maryam Jameel & Ryan McCarthy, Poorly Protected Postal Workers Are Catching COVID-19 by the Thousands. It’s One More Threat to Voting by Mail., ProPublica (Sept. 18, 2020, 5:00 AM), https://www.propublica.org/article/poorly-protected-postal-workers-are-catching-covid-19-by-the-thousands-its-one-more-threat-to-voting-by-mail#:~:text=The%20total%20number%20of%20postal,%2D19%2C%20according%20to%20USPS. [https://perma.cc/5KWR-DRVM]. ↑

- .See generally Jeffrey R. Henig, Privatization in the United States: Theory and Practice, 104 Pol. Sci. Q. 649 (1989); Michal Laurie Tingle, Privatization and the Reagan Administration: Ideology and Application, 6 Yale L. & Pol’y Rev. 229 (1988); John B. Goodman & Gary W. Loveman, Does Privatization Serve the Public Interest?, Harv. Bus. Rev., Nov.–Dec. 1991, https://hbr.org/1991/11/does-privatization-serve-the-public-interest.). [https://perma.cc/YJ9D-J6EQ]. ↑

- .Goodman & Loveman, supra note 55. ↑

- .See id. ↑

- .See, e.g., Mark Paul and Johanna Bozuwa, Can Public Ownership of Utilities Be Part of the Climate Solution?, Forbes (Sept. 13, 2019, 1:36 PM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/washingtonbytes/2019/09/13/can-public-ownership-of-utilities-be-part-of-the-climate-solution/#6f4614e02296 [https://perma.cc/PA2N-QHCA]. ↑

- .See, e.g., Matthew Titolo, Privatization and the Market Frame, 60 Buff. L. Rev. 493, 539–55 (2012). ↑

- .Jon D. Michaels, Privatization’s Pretensions, 77 U. Chi. L. Rev. 717, 778–80 (2010); see Edward Rubin, The Possibilities and Limits of Privatization, 123 Harv. L. Rev. 890, 895–96 (2010). ↑

- .Titolo, supra note 59, at 547. ↑

- .See Andy Kim, The Pros and Cons of Privatizing Government Functions, Governing (Dec. 2010), https://www.governing.com/topics/mgmt/pros-cons-privatizing-government-functions.html [https://perma.cc/BZE6-P6W7] (“If [a private company] can cut corners in any way, they often do.”); Laura Padin, Report: Outsourcing of Federal Jobs to Temp Agencies has Doubled Under Trump Administration, Nat’t Emp’t Law Project (June 19, 2019), https://www.nelp.org/news-releases/report-outsourcing-federal-jobs-temporary-staffing-agencies-doubled-trump-administration/ [https://perma.cc/9KT5-PD5G] (“Outsourcing work to temporary help service agencies degrades the qualities of these jobs.”). ↑

- .Government by Contract: Outsourcing and American Democracy (Jody Freeman & Martha Minow eds., 2009). ↑

- .Molly Ball, The Privatization Backlash, Atlantic (Apr. 23, 2014), https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/04/city-state-governments-privatization-contracting-backlash/361016/?gclid=Cj0KCQjwnqH7BRDdARIsACTSAdsc1WnACxyxYISAXp40-JNTUEYCdlXG0Qu8NQb9Fwfb-gru6kKXsfAaAplOEALw_wcB [https://perma.cc/2PXH-D8YA]. ↑

- .See, e.g., In re Marvel Entertainment Grp., Inc., 273 B.R. 58, 78–80 (D. Del. 2002); In re Walt Disney Co. Derivative Litigation, 906 A.2d 27, 52 (Del. 2006); eBay Domestic Holdings, Inc. v. Newmark, 16 A.3d 1, 40–41 (Del. Ch. 2010); Dodge v. Ford Motor Co., 170 N.W. 668, 684 (Mich. 1919). ↑

- .See, e.g., Model Bus. Corp. Act § 1.40 (2016) (Am. Bar. Ass’n) (defining “corporation” as “a corporation for profit, which is not a foreign corporation, incorporated under or subject to the provisions of this Act”). ↑

- .Delaware has used the Business Judgment Rule to provide significant leeway to its corporate officers and directors to make decisions, just so long as the decisions ultimately benefit the corporation (and are done through well-reasoned processes). See In re Marvel Entertainment Grp., Inc., 273 B.R. at 78–79; In re Walt Disney Co. Derivative Litigation, 906 A.2d at 52, 61–62; eBay Domestic Holdings, Inc., 16 A.3d at 40–41. ↑

- .See Lenore Palladino & Kristina Karlson, Towards Accountable Capitalism: Remaking Corporate Law Through Stakeholder Governance, Harv. L. Sch. F. on Corp. Governance (Feb. 11, 2019), https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2019/02/11/towards-accountable-capitalism-remaking-corporate-law-through-stakeholder-governance/ [https://perma.cc/CDA9-6X4F]. ↑

- .State by State Status of Legislation, Benefit Corp., https://benefitcorp.net/policymakers/state-by-state-status [https://perma.cc/VUD2-WU5E]. ↑

- .Certification, Certified B Corp., https://bcorporation.net/certification [https://perma.cc/R593-ZC2T]. ↑

- .The triple bottom line is a phrase to connote a corporation’s willingness to report on issues outside of its typical financial structure. Wayne Norman & Chris MacDonald, Getting to the Bottom of “Triple Bottom Line”, 14 Bus. Ethics Q. 243, 243 (2004). Typically, reporting includes “People, Planet, [and] Profit,” or environmental, social, and governance issues, leading to the alternative label of ESG reporting. See Certified B Corp, https://bcorporation.net/ [https://perma.cc/ZUZ8-Y8D6]; Hank Boerner, Sustainability and ESG Reporting Frameworks: Issuers Have GAAP and IFRS for Reporting Financials—What About Reporting for Intangibles and Non-Financials?, Corp. Fin. Rev., Mar.–Apr. 2011, at 34, 35–36. ↑

- .170 N.W. 668, 684 (Mich. 1919). ↑

- .Lynn A. Stout, The Shareholder Value Myth, Cornell L. Fac. Publications, Apr. 2013; Stephen M. Bainbridge, Director Primacy: The Means and Ends of Corporate Governance, 97 Nw. U. L. Rev. 547, 605–06 (2003). ↑

- .Id. at 563; Margaret M. Blair & Lynn A. Stout, A Team Production Theory of Corporate Law, 85 Va. L. Rev. 247, 248–49 (1999). ↑

- .See, e.g., In re Walt Disney Co. Deriv. Litig., 906 A.2d 27, 52 (Del. 2006). ↑

- .See, e.g., In re USDigital, Inc., 443 B.R. 22, 44 (Bankr. D. Del. 2011). ↑

- .See In re Walt Disney Co. Deriv. Litig., 906 A.2d at 62. ↑

- .See Basic, Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224, 228 (1988). ↑

- .Jena Martin, Business and Human Rights: What’s the Board Got To Do With It?, 2013 U. Ill. L. Rev. 959, 968 n.45 (2013). ↑

- .Milton Friedman, The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits, N.Y. Times, Sept. 13, 1970, at SM17 (emphasis added). ↑

- .Introduction to BlackRock, BlackRock, https://www.blackrock.com/sg/en/introduction-to-blackrock [https://perma.cc/6TQB-C6RE]. ↑

- .Larry Fink, Larry Fink’s 2019 Letter to CEOS: Purpose & Profit, BlackRock (2019), https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/2019-larry-fink-ceo-letter [https://perma.cc/5WBA-RSQZ] (calling on CEOs to emphasize “purpose” as a way of simultaneously increasing profit while also creating a sustainable and ethical business model). ↑

- .Id.; see also Andrew Ross Sorkin, World’s Biggest Investor Tells C.E.O.s Purpose Is the ‘Animating Force’ for Profits, NY Times (Jan. 17, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/17/business/dealbook/blackrock-larry-fink-letter.html [tk perma] (discussing Mr. Fink’s letter and its call to businesses to make a “positive contribution to society”). ↑

- .The single greatest investor group to come of age in the United States within the next ten years is also the group of investors who believe that businesses should care more about societal impacts then they currently do. Robert G. Eccles & Svetlana Klimenko, The Investor Revolution, Harv. Bus. Rev., May–June 2019, https://hbr.org/2019/05/the-investor-revolution [https://perma.cc/9ZQD-SG8W]. In that sense, Fink’s declaration could be seen as heralding a call to those investors to deposit their money in the BlackRock fund with their forward-looking ways. ↑

- .Indeed, a whole field has developed within the last ten years to mark this growing awareness: the business and human rights field. For an overview of the history of this discussion, particularly at the UN level, see generally Jena Martin Amerson,“The End of the Beginning?”: A Comprehensive Look at the U.N.’s Business and Human Rights Agenda from a Bystander Perspective, 17 Fordham J. Corp. & Fin. L. 871 (2012). ↑

- .Dominic Barton & Mark Wiseman, Focusing Capital on the Long Term, Harv. Bus. Rev., Jan.–Feb. 2014, https://hbr.org/2014/01/focusing-capital-on-the-long-term [https://perma.cc/YG3Y-5YYG]. ↑

- .Karen Kunz & Jena Martin, Into the Breech: The Increasing Gap between Algorithmic Trading and Securities Regulation, 47 J. Fin. Serv. Res. 135, 136, 150 (2015). ↑

- .See Press Release, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, SEC Sues Former Top Officers of Sunbeam Corporation and Arthur Andersen Auditor in Connection with Massive Financial Fraud (May 15, 2001) (available at https://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/lr17001.htm). ↑

- .Albert O. Trostel & Mary Lippitt Nichols, Privately-Held and Publicly-Held Companies: A Comparison of Strategic Choices and Management Processes, 25 Academy of Mgm’t J. 47, 49 (1982). Trostel and Nichols observe:[O]wners of the privately-held company often consist of a small group of entrepreneurially oriented or at least entrepreneurially socialized people. . . . Because their investment is not readily marketable, they are required to take a relatively long-term view. With the steadying influence of the longer view replaced in the publicly-held firm by the impersonal information of the movement of the stock price, one could expect the management of the public firm to focus greater attention on the next quarter’s earnings. . . .

Id. ↑

- .Joseph DeBenedetti, Examples of Profit Maximization, Chron, https://smallbusiness.chron.com/examples-profit-maximization-81432.html [https://perma.cc/A6MB-WGZJ]. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .E.g., Daniel Rowe, Lessons from the Steel Crisis of the 1980s, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/lessons-from-the-steel-crisis-of-the-1980s-57751 [https://perma.cc/TK7R-D5KG] (discussing the “devastation” to surrounding communities when steel producers left). ↑

- .E.g., Press Release, supra note 88. ↑

- .See, e.g., Andrew C. Revkin, Retro Report: Love Canal and its Mixed Legacy, N.Y. Times (Nov. 25, 2013), https://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/25/booming/love-canal-and-its-mixed-legacy.html [https://perma.cc/LWE3-Q3L4] (discussing the negative environmental impact of Hooker Chemical (now Occidental Petroleum) dumping hazardous chemicals into a local New York community in the 1970s); Spectacular Failures: The Toxic Tale of the Love Canal Fail, American Public Media (Aug. 24, 2020), https://www.spectacularfailures.org/story/2020/08/24/spectacular-failures-the-toxic-tale-of-the-love-canal-fail-transcript [https://perma.cc/HW9V-DNSH] (interviewing Andy Hoffman, a professor of sustainable enterprise at the University of Michigan, who states: “Why did [the company] do this? Because it was really cheap. And it’s a lot more expensive to deal with [the waste] by burning it or any of the other technologies that were available. So let’s not take the profit motive out of this.”) ↑

- .Bogage, supra note 54. ↑

- .Max Greenwood, Trump: Amazon ‘Scam’ Costing Postal Service ‘Billions’, The Hill (Mar. 31, 2018, 9:23 AM), https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/381092-trump-amazon-scam-costing-postal-service-billions [https://perma.cc/B9M6-AHU2]. ↑

- .Lisa Rein & Jacob Bogage, Trump Says He Will Block Coronavirus Aid for U.S. Postal Service If It Doesn’t Hike Prices Immediately, Wash. Post (Apr. 24, 2020, 6:22 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/us-policy/2020/04/24/trump-postal-service-loan-treasury/ [https://perma.cc/WAL6-9Q3Q]. ↑

- .Tim Mak, Tom Dreisbach & Dina Temple-Raston, Who Is Louis DeJoy? U.S. Postmaster General in Spotlight ahead of 2020 Election, NPR (Aug. 21, 2020, 6:58 AM), https://www.npr.org/2020/08/21/904346060/postmaster-general-faces-intense-scrutiny-amid-allegations-of-political-motives [https://perma.cc/STH4-E5KY]. Unlike DeJoy, the previous Postmaster General, Megan Brennan, came up through the ranks of USPS. See Josh Dawsey, Lisa Rein & Jacob Bogage, Top Republican Fundraiser and Trump Ally Named Postmaster General, Giving President New Influence over Postal Service, Wash. Post (May 6, 2020, 9:05 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/top-republican-fundraiser-and-trump-ally-to-be-named-postmaster-general-giving-president-new-influence-over-postal-service-officials-say/2020/05/06/25cde93c-8fd4-11ea-8df0-ee33c3f5b0d6_story.html [https://perma.cc/LXB5-C6KB]. ↑

- .Amy Gardner & Paul Kane, House Oversight Committee Will Investigate Louis DeJoy Following Claims He Pressured Employees to Make Campaign Donations, Wash. Post (Sept. 8, 2020, 5:45 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/louis-dejoy-house-investigation/2020/09/07/d13be1ae-f175-11ea-bc45-e5d48ab44b9f_story.html [https://perma.cc/76DF-SCQB]. ↑

- .See Jacob Bogage, Postal Service Overhauls Leadership as Democrats Press for Investigation of Mail Delays, Wash. Post (Aug. 7, 2020, 6:10 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/08/07/postal-service-investigation-dejoy/ [https://perma.cc/Y4N3-CF9E]; Kevin Breuninger, USPS Chief Louis Dejoy Says There’s ‘No Intention to’ Bring Back Removed Mail-Sorting Machines, CNBC (Aug. 21, 2020, 10:35 AM), https://www.cnbc.com/2020/08/21/usps-chief-dejoy-no-intention-to-bring-back-removed-mail-sorting-machines.html [https://perma.cc/W2XV-XHH6]. ↑

- .See Alison Durkee, New York AG Files Multistate Lawsuit, Joins More than 20 States Suing Postal Service over DeJoy’s Changes, Forbes (Aug. 25, 2020, 3:09 PM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/alisondurkee/2020/08/25/more-than-20-states-attorneys-general-suing-postal-service-usps-changes-despite-dejoy-reversal/#3feac4ff4533 [https://perma.cc/7HCJ-7WBC]. ↑

- .Washington v. Trump, No. 1:20-CV-03127-SAB, 2020 WL 5568557, at *4 (E.D. Wash. Sept. 17, 2020) (order granting plaintiffs’ motion for preliminary injunction) (emphasis added). The Trump administration has continued this strategy in the wake of his election loss to President-elect Biden. Specifically, in a statement released after the election Trump stated: “Our campaign will start prosecuting our case in court to ensure election laws are fully upheld and the rightful winner is seated . . . The American People are entitled to an honest election: that means counting all legal ballots, and not counting any illegal ballots.” Miles Park, Trump Election Lawsuits Have Mostly Failed. Here’s What They Tried, NPR (Nov. 10, 2020, 8:00 AM), https://www.npr.org/2020/11/10/933112418/the-trump-campaign-has-had-almost-no-legal-success-this-month-heres-what-they-ve [https://perma.cc/WX9R-J94F]. ↑

- .See Task Force on the U.S. Postal Sys., Dep’t of the Treasury, United States Postal Service: A Sustainable Path Forward (2018); Task Force on the United States Postal System, 83 Fed. Reg. 17,281 (Apr. 18, 2018). ↑

- .Off. Mgmt. & Budget, Delivering Government Solutions in the 21st Century 68 (2018). This report states:Like many European nations, the United States could privatize its postal operator while maintaining strong regulatory oversight to ensure fair competition and reasonable prices for customers. A private Postal Service with independence from congressional mandates could more flexibly manage the decline of First-Class mail while continuing to provide needed services to American communities.

Id.; see also Task Force on the U.S. Postal Sys., supra note 103, at 29–31 (naming five countries with privatized postal systems); Rick Newman, Why the U.K. Can Privatize Its Postal Service, but the U.S. Can’t, Yahoo! Fin. (Oct. 11, 2013), https://finance.yahoo.com/blogs/the-exchange/why-u-k-privatize-postal-u-t-195031232.html [https://perma.cc/J6JB-WVF7] (noting that only five European countries have privatized their postal systems). ↑

- .Task Force on the U.S. Postal Sys., supra note 103, at 34. ↑

- .Id. at 35. ↑

- .Id. at 33–38. ↑

- .Id. at 33. However, this overlooks the fact that many rural Americans don’t have access to the internet, making online communications problematic. See John Busby & Julia Tanberk, FCC Reports Broadband Unavailable to 21.3 Million Americans, BroadbandNow Study Indicates 42 Million Do Not Have Access, BroadbandNow Research (Feb. 3, 2020) https://broadbandnow.com/research/fcc-underestimates-unserved-by-50-percent [https://perma.cc/MA93-HDAA]. ↑

- .Task Force on the U.S. Postal Sys., supra note 103, at 33. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .See Jenny Anderson, Cities Debate Privatizing Public Infrastructure, N.Y. Times (Aug. 26, 2008), https://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/27/business/27fund.html [https://perma.cc/GL3F-SV4T]. ↑

- .See Nat’l Ass’n Letter Carriers, supra note 53, at 3–4. ↑

- .Task Force on the U.S. Postal Sys., supra note 103, at 2. ↑

- .Nat’l Ass’n Letter Carriers, supra note 53, at 4–5. ↑

- .Id.; see also USPS Fairness Act, H.R. 2382, 116th Cong. (as received in Senate, Feb. 10, 2020); Lydia DePillis, White House Backs Off Privatizing the Postal Service, CNN (Dec. 4, 2018, 5:27 PM), https://www.cnn.com/2018/12/04/politics/treasury-usps-report/index.html [https://perma.cc/XE2J-RESR]. ↑

- .Nat’l Ass’n Letter Carriers, supra note 53, at 6. ↑

- .Spross, supra note 50. ↑

- .Jennifer Smith, Trump’s Fix for Postal Service: Privatize It, Wall St. J. (June 22, 2018, 5:30 AM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/trumps-fix-for-postal-service-privatize-it-1529659801 [https://perma.cc/BZH5-WR5Z]. ↑

- .See Cep, supra note 28. Cep states:But if the coronavirus kills the Postal Service, its death will have been hastened, as so many deaths are right now, by an underlying condition: for the past forty years, Republicans have been seeking to starve, strangle, and sabotage it, hoping to privatize one of the oldest and most important public goods in American history.

Id. ↑

- .Erik Sherman, 7 Reasons Why Privatizing the Postal System Is Ridiculous and Foolish, Forbes (Aug. 17, 2020, 2:51 PM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/eriksherman/2020/08/17/7-reasons-privatizing-postal-system-usps/ [https://perma.cc/ZFN3-Z4GY] (“There is no private company even slightly prepared to take on the workload the federal postal system requires.”); Jake Bittle, Bernie Sanders Is to Deliver a Commonsense Plan to Save the Postal Service, Nation (June 7, 2018), https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/bernie-sanders-commonsense-plan-save-postal-service/ [https://perma.cc/E94S-DAKZ]. ↑

- .See DePillis, supra note 115; About, Coal. for 21st Century Postal Serv., https://21stcenturypostal.org/about/ [https://perma.cc/TE6S-2ME4] (raising awareness “of the indispensable role USPS continues to play in the nation’s commerce and communications, and the jobs and business it supports”). ↑

- .Eric Katz, Americans Support Postal Service Bailout, Polls Show, Gov’t Exec. (May 1, 2020), https://www.govexec.com/management/2020/05/americans-support-postal-service-bailout-polls-show/165088/ [https://perma.cc/A7MJ-AS5P]. ↑

- .E.g., Michael Hiltzik, Column: The Postal Service Is America’s Most Popular Government Agency. Why Does Trump Hate It?, L.A. Times (Jan. 9, 2020, 11:17 AM), https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2020-01-09/postal-service-trump [https://perma.cc/H2YT-N4GV]. ↑

- .See Jen Kirby, Postmaster General Hits Pause on USPS Changes until after Election Amid Public Outcry, Vox (Aug. 18, 2020, 5:20 PM), https://www.vox.com/2020/8/18/21374014/post-office-usps-louis-dejoy-statement-trump-mail-in-voting [https://perma.cc/6FMU-U534]. ↑

- .Smith, supra note 118. ↑

- .Nat’l Ass’n Letter Carriers, supra note 53, at 1. ↑

- . A Look at Other Countries’ Postal Reform Efforts: Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Post Office and Civil Service, Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs; and the Subcommittee on the Postal Service, House Committee on Government Reform and Oversight, 104th Cong. 3 (1996) (statement of Michael E. Motley, Associate Director, Government Business Operations Issues) (acknowledging that, compared to other countries with privatized postal services, the U.S. Postal Service handles “at least seven times the mail volume”); Jake Bittle, In Rural America, the Postal Service Is Already Collapsing, Nation (May 3, 2018), https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/in-rural-america-the-postal-service-is-already-collapsing/ [https://perma.cc/66Q5-K2ZW]. Bittle found that:[R]ural carriers deliver letters and packages in areas where private companies like FedEx and UPS can’t make a profit, and in small towns where brick-and-mortar stores have been vanishing. This means that Amazon, which ships an estimated 40[%] of its packages through the USPS, relies on the agency even more in rural areas, where no one else will fulfill its orders.

Id. ↑

- .Nat’l Ass’n Letter Carriers, supra note 45, at 11; Fredric V. Rolando, The White House Postal Task Force Report: Fundamentally Flawed, Postal Rec., Apr. 2019, at 1, 1. ↑

- .See supra note 6 and accompanying text. ↑

- .Cantrell, supra note 5. ↑

- .Busby & Tanberk, supra note 108 (estimating this number could be as high as 42 million). ↑

- .Joe Davidson, Should the post office also be a bank?, Wash. Post (Oct. 30, 2015 10:40 AM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/federal-eye/wp/2015/10/29/should-the-post-office-also-be-a-bank/ [https://perma.cc/G8YF-QBBU] (describing the history of the Post Office as a bank: “Postal banking, known as the Postal Savings System, began operation in 1911 and officially ended in 1967”). ↑

- .See Victor Pickard, Instead of Killing the US Postal System, Let’s Expand It, Nation (May 7, 2020), https://www.thenation.com/article/society/usps-funding-local-media/ [https://perma.cc/62K4-8SX2] (proposing that the U.S. Postal System infrastructure should be expanded to offer public services, including postal banking and community news services). ↑

- .Davidson, supra note 132. ↑

- .U.S. Postal Serv., FY2019 Annual Report to Congress 1 (2019). ↑

- .See Rubio, supra note 33, at 193–99. ↑