The Migrant Farmworkers’ Case for Eliminating Small-Firm Exemptions in Antidiscrimination Law

Introduction

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is one of the pillars of antidiscrimination law.[1] It bans discrimination in the workplace on the basis of “race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”[2] Much litigation and scholarly analysis has centered on what constitutes discrimination on the basis of each of these categories, but almost forgotten as an access-to-justice issue is the fact that, as a threshold matter, Title VII does not apply to all employers.

Title VII defines “employer” as “a person engaged in an industry affecting commerce who has fifteen or more employees for each working day in each of twenty or more calendar weeks in the current or preceding calendar year . . . .”[3] Employers with fewer than fifteen employees (often referred to as “small firms”) are exempted from Title VII requirements. To the extent that scholars and courts have analyzed the small-firm exemption in the definition of “employer,” most discussion has to do with the procedural implications of the threshold or the hidden difficulties of calculating whether an employer does or does not have fifteen “employees.”[4]

The few authors who have addressed the injustice presented by the small-firm exemption to Title VII (also referred to in this Note as the “minimum-employee threshold”) have suggested solutions including more robust enforcement mechanisms for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), eliminating the threshold, or using federalism to incentivize state laws to cover employers exempted by Title VII.[5] This Note advocates for the expansion of Title VII at the federal level by decreasing the minimum-employee threshold provided in the definition of “employer” or eliminating it altogether. This Note focuses on the coverage gap left by state laws as a compelling justification for alteration of Title VII. In particular, I use an analysis of existing state law in the South to complicate and challenge the suggestion that state-law innovation is the best solution to the lack of protection created by the small-firm exemption. Through the example of H-2A migrant farmworkers in the South, I demonstrate that state law fails to pick up where federal law leaves off. State laws are not currently a sufficient alternative to Title VII protection, and in the South, I do not foresee state laws becoming a viable alternative. I hope to revitalize the argument for eliminating or lowering the threshold at the federal level in order to increase access to remedies for employment discrimination, particularly for migrant farmworkers.

In Part I, I examine the legislative history of the original small-firm exemption to Title VII present in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and subsequently of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 (amending Title VII) in order to discern the reasoning and salient concerns of the legislators when they set the threshold. The definition of “employer” initially had a threshold of twenty-five employees but was lowered to fifteen employees in 1972. In Part II, I synthesize contemporary defenses and criticisms of the small-firm exemption. Interestingly, the current arguments for and against the exemption mirror in important ways the concerns of the Senators who crafted the exemption. In addition to responding to the defenses of the exemption, this Part sets forth additional normative rationales for why small businesses should be bound by antidiscrimination law in the same way as big businesses.

Part III turns to the interaction between state and federal antidiscrimination law and surveys existing state antidiscrimination statutes in the South. In Part IV, I introduce information on the specific circumstances of H-2A migrant farmworkers, a particularly vulnerable group of workers who are excluded from both Title VII and state antidiscrimination law at staggering rates. I hope that this case study, along with contextual information about the difficulty of changing state antidiscrimination law in the South, serves as a compelling new argument against the small-firm exemption to Title VII. To adequately combat discrimination in the workplace and fully realize the goals of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, I advocate for full elimination of any small-firm exemption in Title VII’s definition of “employer.” However, as discussed in my concluding remarks, passing such an amendment is a daunting task before a Republican-controlled Senate; as such, a five-person threshold is an acceptable starting compromise that would extend coverage significantly while acknowledging the concerns of those who defend the small-firm exemption.

I. Legislative History

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 defines “employers” and thus, with its passage, created a small-firm exemption. The 1964 Act had a twenty-five-employee threshold, which was then lowered to a fifteen-employee threshold in the Equal Employment Act of 1972. The legislative history at each of these moments sheds light on why each threshold was implemented and how legislators thought about where to “draw the line” on Title VII coverage.

A. Pertinent Legislative History of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964[6]

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was the most sweeping collection of civil rights legislation ever passed in United States history.[7] But it did not come easily. Debate on the Civil Rights Act resulted in the longest continuous Senate debate to date, lasting over 500 hours.[8] Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (creating expansive protection against employment discrimination) was an extremely controversial section of the legislation[9] and was nearly eliminated in its entirety on several occasions as senators tried to find compromises that would salvage the Act as a whole.[10] The legislative history of the passage of Title VII, especially the congressmembers’ commentary pertaining to the small-firm exemption, provides insight into the rationale for the exemption—a rationale that, as discussed in Part II, is problematic.

While President John F. Kennedy had approved of equal-employment initiatives and supported the bill that would become the Civil Rights Act, Kennedy’s original 1963 civil rights bill did not include the provisions that we now recognize as Title VII.[11] Those portions of the legislation were built out in committee as the bill moved through the House of Representatives.[12] During consideration by a subcommittee of the Judiciary Committee, representatives removed Title VII of the original bill and replaced it with content from H.R. 405, including, for the first time, the definition of “employer.”[13] When the relevant bill, H.R. 7152, left the House of Representatives, it retained a definition of “employer” as “a person engaged in an industry affecting commerce who has twenty-five or more employees.”[14]

While most congressional debate on Title VII focused on exemptions for special interest groups and the structure of the EEOC,[15] two proposed changes to the definition of “employer” are worth examining in more detail. Between when H.R. 7152 was presented to the House and when it was finally approved by the Senate, the definition of “employer” was expanded to add the qualification that it apply only to employers that have twenty-five employees “for each working day in each of 20 or more calendar weeks.”[16] This effectively excluded seasonal workers. Before the change was made, Senator Everett Dirksen expressed some concern that the definition of “employer” was too vague and confusing.[17] Senator Joseph Clark responded that “employer” was to have the normal dictionary meaning—that is, that employers would be bound in weeks when they had over twenty-five workers and not bound in weeks when they had under twenty-five workers.[18] Dirksen’s response was to compare the bill to other legislative schemes (such as the Illinois Fair Employment Practices law) that covered employers who had the threshold number of employees for a certain number of weeks in a year.[19] Later, once the change had been made to the bill, Dirksen confirmed that the “20 or more calendar weeks” addition was intended in part to exclude seasonal workers.[20] As will be discussed in Part IV, seasonal agricultural workers have been especially under-covered by Title VII because of both the employee threshold and the twenty-weeks requirement.[21]

But perhaps the most illuminating discussion on the original definition of “employer” in Title VII occurred with the Cotton amendment. In April 1964, right as leaders of the Senate hoped to finally vote on cloture, several Republican Senators who were dissatisfied with Title VII introduced three final amendments.[22] One such amendment, offered by Senator Norris Cotton, was that the definition of “employer” be changed to only cover entities with 100 or more employees.[23] Cotton expressed concern that small family businesses would be burdened in the form of being prevented from hiring from within their community network.[24] He suggested that big businesses may be regulated because their hiring choices are “impersonal” but that the small business entity is a personal endeavor where employers should be able to choose for themselves who to hire.[25] He further suggested that Title VII as drafted served no purpose other than to burden these small businesses unnecessarily.[26] Senator Case echoed the concern that Title VII would cause “harassment of small businessmen.”[27] This concern about the burden caused to small businesses persists today.[28]

Senator Dirksen, in opposing the Cotton amendment, contended that moving the threshold to 100 would eviscerate the force of Title VII and strip it of any notion of equity.[29] Dirksen expressed a desire that the law apply to everyone.[30] He noted that when the Senate Committee workshopped the bill before H.R. 7152 arrived, the Committee members looked at state protections, some of which covered employers of five or fewer employees, and felt that the role of the federal law in the antidiscrimination sphere was to mirror state protections.[31] Moving the threshold to 100, he asserted, would “produce a gaping hole” in protections.[32] But a threshold of twenty-five employees, argued other Senators, appropriately captured the moment where a small business reliant on personal relationships in hiring became big enough to deserve regulation.[33]

Senator Hubert Humphrey also opposed the Cotton amendment. Interestingly, Humphrey partially founded his opposition in the interaction between federal and state law. He stated that moving to a 100-employee threshold would create drastic disparities in the level of coverage provided by state and federal employment-discrimination law.[34] The underlying goal of Title VII, he argued, was to give states the first opportunity to combat discrimination and to let the federal government act as a second line of defense.[35] Humphrey was not sympathetic to the argument that broader coverage would put a burden on small businesses. He compared Title VII to other federal legislative schemes and pointed out that while these other regulations placed analogous burdens, they had much narrower or nonexistent exemptions for small-firm employers.[36] For example, he pointed out that the Fair Labor Standards Act had a two-employee minimum for coverage at the time, and the National Labor Relations Act had no employee minimum.[37]

After the Cotton amendment was defeated,[38] the Senate voted to approve H.R. 7152, and it returned to the House of Representatives, where the bill was quickly adopted.[39] The public law as enacted staggered coverage: for the first year after the effective date of the law, entities with fewer than 100 employees were not covered; in the second year, entities with fewer than seventy-five employees were not bound; in the third year, coverage extended to employers of fifty to seventy-four employees; in the fourth year, coverage extended to employers of twenty-five or more people.[40] This gradual implementation of the law was justified by its supporters as further insurance that the burden of compliance would not fall too quickly or too heavily on small businesses.[41]

B. Legislative History of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972

Against the backdrop of the legislative history of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the legislative history of its 1972 amendments demonstrates that, even from the beginning, some legislators recognized that exempting entire categories of employers was inconsistent with fully realizing the goals of Title VII. The Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 amended Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[42] Among other things, it extended the definition of “employer” to those who employed fifteen or more employees for each working day of at least twenty weeks of the calendar year.[43]

Starting in 1965 with the 89th Congress, barely a year after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, members of the House and Senate began offering bills that would expand the scope of Title VII. The first such bill was H.R. 8998, which proposed more robust enforcement power for the EEOC and would have changed the original twenty-five-employee threshold to an eight-employee threshold.[44] This bill never made it to the Senate. As stated at the beginning of H.R. 8998, the goal of these bills was to make Title VII more effective.[45] H.R. 10065, a very similar bill with an eight-employee threshold, was passed by the House on April 27, 1966, but was never acted upon by the Senate.[46] During the 91st Congress (1969–1971), a number of similar bills were offered in one chamber or another but failed for various reasons.[47]

What would eventually become the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 began in the House of Representatives in the 92nd Congress as H.R. 1746, introduced on January 22, 1971.[48] This bill, among other amendments to Title VII, extended coverage to employers with eight or more employees.[49] Discussion at the subcommittee hearing for H.R. 1746 regarding the shift in coverage from twenty-five to eight employees illustrates some of the contemporaneous support and opposition to such a shift.

For example, Robert Nystrom of Motorola, Inc., testified against the expansion, arguing that the greatly increased number of cases would burden the EEOC.[50] He also insisted that small employers did not need to be covered by Title VII because once small employers heard about the work of the EEOC against discrimination at larger employers, compliance would “filter down” to small employers, and they would become compliant of their own accord.[51] In support of the expansion, the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) testified that “some of the worst discrimination in employment occurs in small establishments.”[52] The House of Representatives Committee on Education and Labor, in their committee report of H.R. 1746, noted that:

[D]iscrimination in employment is contrary to the national policy and equally invidious whether practiced by small or large employers. Because of the existing limitation in the bill proscribing the coverage of Title VII to 25 or more employees or members, a large segment of the Nation’s work force is excluded from an effective Federal remedy to redress employment discrimination. For the reasons already stated in earlier sections of this report, the committee feels that the Commission’s remedial power should also be available to all segments of the work force. With the amendment proposed by the bill, Federal equal employment protection will be assured to virtually every segment of the Nation’s work force.[53]

On January 19, 1972, the Senate began debate on S. 2515, the companion bill to H.R. 1746.[54] This bill retained the eight-employee threshold, until Senator Samuel Ervin offered an amendment to revert to the twenty-five-employee threshold.[55] Then, Senator Harrison Williams offered to amend the Ervin amendment from twenty-five to fifteen employees.[56] Senator Ervin opposed the Williams amendment, commenting that reducing the employee threshold would deeply burden small employers, who tend to have personal relationships with their employees and should be allowed freedom in the hiring process.[57] He went on to say, “The businessman wants members of his own church. He wants members of his own race. He wants people of the same national origin.”[58] The Williams amendment to the Ervin amendment passed in the Senate 56–26, and the fifteen-person threshold became part of S. 2515.[59] The Conference Committee adopted the fifteen-person threshold into H.R. 1746, which was enacted into law as Public Law Number 92-261 on March 24, 1972.[60]

From the legislative history of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, we see the competing arguments for and against expansion of protection to employees of smaller entities. Those favoring expanded protection tended to be concerned with the number of workers without protection and the belief that the law should protect workers from discrimination irrespective of the size of the business. Opponents of such an expansion prioritized the burden that would fall on the EEOC and on the small businesses themselves or suggested that the liberty of small employers in choosing who to hire outweighed the value of protective laws. Many of these same arguments for and against the small-firm exemption persist today.

II. Defenses and Criticisms of the Small-Firm Exemption to Title VII

While the pros and cons of small-firm exemptions to statutory and regulatory schemes such as Title VII are not discussed very widely,[61] common defenses of the small-firm exemption to Title VII and similar statutory or regulatory schemes tend to fall into several categories. In this Part, I discuss each of these defenses in turn, along with the corresponding responses and rebuttals. While very few authors have critiqued the small-firm exemption for the way that it creates barriers to justice, Pam Jenoff’s and Richard Pierce’s deft responses to defenders of the small-firm exemption lend strength to the argument for expanded coverage of Title VII.[62]

A. Burdensome Costs to Small Firms as Employers

The most prevalent defense of exempting small firms from Title VII is that small firms cannot bear the burdens of compliance.[63] The concerned point both to the preventative costs of complying with antidiscrimination law and implementing it in the workplace, and to the costs of defending litigation for violations of antidiscrimination law.[64] These scenarios are further affected by the idea that, aside from the flat costs of implementation and defending against litigation, small employers cannot take advantage of economies of scale.[65] Costs of compliance do not always change based on how many employees the firm has—for example, the cost of having a training on sexual harassment costs about the same amount whether you are presenting to five employees or twenty—but the small firm cannot bear these costs as easily.[66] Additionally, it has been argued that the costs of compliance hinder the ability of the small firm to be competitive in the market.[67]

Among the concerns for the costs placed on small businesses by making them comply with antidiscrimination law is the suggestion that it is more efficient not to regulate small businesses—i.e., that the cost of regulation is so high that it outweighs any positive effects towards eliminating discrimination. In a strictly mathematical sense using limited variables, it may be true that exempting small businesses from Title VII is economically efficient.[68] However, once transaction costs (such as the burdens of policing the line of who is covered and who is not) are considered, it is less clear that the exemption is efficient, even in a strictly financial sense.[69] A related idea is that, because big business is such a powerful political interest (the assumption that “big business is bad” is so central to the U.S. psyche that it is barely worth stating), and because big-business interests dominate politics, big businesses deserve regulation but small businesses do not.[70] However, despite the deep pedigree of our sympathy for small businesses, they are an extremely powerful special interest group that is systematically privileged in regulatory schemes.[71]

Given the salience of the concern for the burden of antidiscrimination law on small business, it is important to acknowledge the weight of this concern. Having a lawsuit filed against an employer causes great inconvenience to the employer—even if the lawsuit is dismissed swiftly. A defendant will likely incur costs of consulting with an attorney, filing a motion to dismiss, beginning discovery, or filing for summary judgment. However, though we imagine a paradigm mom-and-pop shop slammed with a huge lawsuit and trying to defend itself at trial, the reality is that most antidiscrimination cases never get to trial, and settlement amounts tend to be modest.[72]

Additionally, there is a normative argument that combatting widespread discrimination in the workplace is so important that it is worth imposing the costs on small businesses, even if they are somewhat burdensome. At the time of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, the House Committee affirmed that “discrimination in employment is . . . equally invidious whether practiced by small or large employers.”[73] Senate reports contemporaneous to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 stated that the purpose of Congress was to secure rights for all persons and to remove all discriminatory restrictions in employment opportunity.[74] With such a sweeping and inclusive stated purpose, demonstrating an intent to reform employment settings completely, it is evident that the focus was creating change, even if burdens were imposed on employers (though, as discussed above, compromises were made so as not to make the burdens too great). To continue excluding so many workers from Title VII just because of the potential burden to some employers is an insult to the stated purposes of Title VII.[75]

Furthermore, keeping the threshold at fifteen employees is a poor fit if the concern is for the smallest of the small mom-and-pop shops. Other statutory and regulatory schemes, such as the Occupational Safety and Health Act, have no minimum-employee threshold because the safety interest is considered so important.[76] Others, such as the Fair Labor Standards Act, have a threshold based on revenue rather than employees.[77] Still yet, laws such as the Immigration Reform and Control Act prohibit certain types of discrimination for employers of four or more employees.[78] All of these laws create implementation costs for the employer, but the varying size thresholds seem to bear no correlation to the implementation costs; the more expensive schemes do not systematically exclude small employers, or vice versa.[79] If cost to small employers remains a driving concern, other measures, such as revenue of the business, may be better proxies for how the employer will be burdened by compliance than the number of employees.[80] Or perhaps the better compromise is to set the threshold much lower (e.g., at five employees) so that the very smallest employers, arguably those least prepared for the costs of implementation and litigation, are still exempted, but the coverage gap is not as shocking as it is now.[81]

B. Small Firms Depend on Personal Relationships Between Employer and Employee

The second broad category of concern stems from the idea that small businesses rely on personal relationships in their hiring.[82] Debate in the Senate at the time of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and again leading up to the 1972 amendments when members of Congress proposed changes to the employee threshold, reflects that the Senators in favor of small-firm exemptions were also concerned with the personal relationships relied upon by small businesses, or at least named this as a concern.[83] From this reasoning, it would follow that, because the small firm does not have access to large hiring pools and the employer presumably works closely with each employee, the employer should be able to choose employees that they get along with, i.e., that have similar characteristics to the employer.[84] Another argument offered is that the employer–employee relationship in small businesses is the type of private relationship that the government should not be able to regulate.[85] When the exemption was debated in the Senate, Senators even made the comparison between choosing employees and choosing a wife, suggesting that the two were analogous and neither should be regulated by the government.[86]

However, Jenoff points out that medium and large businesses also have personal relationships with their employees and would probably prefer to be able to choose employees that are friends or family.[87] In the context of the smallest businesses, it is tempting to allude to government interference with “personal” decisions.[88] At a normative level, however, the type of discrimination prohibited in Title VII (e.g., sexual harassment) is unacceptable in any workplace, regardless of how many employees there are or whether the employers prefer to hire friends and family to staff their small firm.[89]

C. Judicial Efficiency and Burdening the EEOC

Third, defenders of the small-firm exemption express concern that, should the scope of Title VII be expanded, litigation would flood the courts.[90] The concern is rooted in the “tension between providing widespread access to the claiming system and managing the workload of the system so that it can effectively . . . resolve disputes.”[91] This is an understandable concern, as providing more employees with the opportunity to file a lawsuit in federal court would most likely lead to considerably more litigation in federal court.[92] Relatedly, if many more people are able to file claims, it may slow down the process for those who are already covered by Title VII.[93] Admittedly, the EEOC has limited resources to follow up on filed complaints.[94] If the EEOC cannot follow up on each claim, then there is limited value in being able to file it; what good is universal coverage to the employee of a small firm if their claim is stuck in a years-long backlog and never resolved?[95]

In response to the “floodgates of litigation” concern, Jenoff points out that this tension is not unique to antidiscrimination law.[96] However, if the goal of Title VII is to challenge the status quo of employment law and catalyze systemic change, arbitrarily excluding a large portion of the workforce for efficiency’s sake is no way to send a message that discrimination everywhere is unacceptable.[97]

D. Small Firms Create Social Good

Another category of support for the small-firm exemption is that small firms create social good and should receive preference as a result. Carlson acknowledges that this rationale leaves small firms with a “license to discriminate” of sorts.[98] However, he counters by suggesting that many employers that we are inclined to tag as “discriminators” are self-employed or have only one or two employees.[99] To the extent that we see employment of all as a good thing, Carlson suggests that perhaps self-employment or running a very small firm is the “most productive” spot in the economy for folks who have trouble finding work elsewhere (because they are discriminatory).[100]

Another argument suggests that exempting small firms actually allows them to discriminate in favor of minorities—that is, that minority small business owners are allowed by this exemption to hire only minority workers.[101]

For those seeking justification of the exemption, it is tempting to believe that it indeed helps minority business owners and is consistent with the purpose of Title VII. Carlson offers examples of immigrant communities where minority-owned small businesses hire only other immigrants.[102] But without those same minority communities stating themselves that widespread exemption from antidiscrimination law is preferable to expansive protection, I do not find the individual anecdotal evidence to be a strong indication that the policy is beneficial across the board. On the contrary, if regulatory exemptions for small businesses are used as a proxy for facilitating minority-owned businesses and the hiring of minorities (because explicit preference of minority hiring would run afoul of current anticlassification structures), it is unclear how providing exemptions to small businesses would actually lead to more opportunity for minority-owned business, in light of the fact that small firms hire fewer minority employees.[103]

There is also an assumption that small businesses are good for the economy. As the syllogism goes, small businesses create the most jobs, and job creation is the best indicator for economic health, so small businesses create economic health.[104] The American mainstream often equates small businesses with the creation of new innovations.[105] Although these statements are so commonly heard that we don’t often challenge them, and we are predisposed to think small business is good, each of these premises can and has been challenged, bringing the entire logic into question.[106] For example, GDP is arguably a better indicator of economic health than is the number of new jobs.[107] Because all firms contribute to GDP, not just big businesses, all businesses should be subject to compliance with Title VII if economic growth is the primary concern.

E. Political Pressure

Carlson explains that perhaps one reason for the continued existence of the small-firm exemption to Title VII is raw politics.[108] At the time of its passage, Title VII was in danger of being eliminated from the Civil Rights Act entirely.[109] Carlson hypothesizes that, of the battles to choose, fighting over the exact number for the small-firm exemption was too risky for pro-Civil Rights Act Senators who didn’t want to lose Title VII altogether.[110] In order to get the votes to pass the Civil Rights Act, this was the compromise that stuck.[111] Or perhaps the Senators who argued for this limited coverage didn’t care about small businesses at all—they just opposed the Act and wanted to trim it in whatever ways they could, and limiting coverage through the definition of “employer” was one way to do so.[112]

This logic may be extended to infer that, in a world of tensely balanced political pressure, proponents of more robust antidiscrimination law choose not to fight this particular point because they don’t want to reopen debate that would make vulnerable the more central aspects of Title VII. And those who oppose more expansive antidiscrimination law cling to the exemption, not to protect small businesses, but to curtail the possible expansion of antidiscrimination law.

This argument is not very compelling for either side. While it may partially explain the genesis of the exemption, it does little to explain the continued existence of the exemption, especially through the 1972 amendment, when eliminating Title VII in its entirety was not a real concern. Additionally, while strategy and compromise are admittedly central to the legislative process, concerns about contemporary political support for Title VII are not a strong enough reason to continue leaving so many workers without protection.

F. Further Negative Externalities of Small-Firm Exemptions

In addition to rebutting the defenses of the small-firm exemptions to Title VII and similar schemes, Pierce and Jenoff identify further negative consequences of exempting small-firm employers from antidiscrimination law. That is, beyond countering the reasons why such an exemption is good, they argue that it is actively bad. The argument is two-fold: Small businesses create social ills and are encouraged to keep doing so because they receive preferential regulatory treatment.[113]

One often-cited example is the work of Harry Holzer, showing through statistical analysis that small firms hire significantly fewer black workers than large firms.[114] Even accounting for the size of the city and other factors that might lead fewer people of color to apply for jobs, the trend holds.[115] Fewer black applicants apply to small firms, and small firms also select a smaller percentage of black applicants than do big firms.[116] This is partly because the small firms do not feel the compliance pressure of the EEOC.[117]

Smaller firms tend to have less formalized human resources departments and may not have any written procedures or safeguards against discrimination in the workplace.[118] Moreover, if the employees of a small firm truly operate like a small family, as some Senators during the debate on Title VII wanted us to believe, discriminatory acts by one may be overlooked by the others more so than in a larger, more formalized workplace.[119]

Small firms have been shown to expose their workers to risks of on-the-job injury at a higher rate, cause proportionally higher levels of air and water pollution, and provide less health care coverage to their workers than big firms.[120] These negative externalities in particular can be tied to the fact that small firms are not subject to the respective federal regulatory schemes.[121] I have described these negative externalities and social ills caused by small businesses, not to defend big business in comparison, but rather to challenge the deference and leeway given to small businesses in the setting of antidiscrimination law. While the concern for burdening small business and regulatory bodies is well taken, I maintain that the normative goal of eliminating workplace discrimination makes expanding coverage of Title VII imperative nonetheless.

III. The Gap Between Federal and State Antidiscrimination Law

With appreciation for the abovementioned defenses and critiques of the small-firm exemption to Title VII, I will now focus on what I believe to be an additional underlying justification for the minimum-employee threshold to Title VII, but one that I find deeply troubling—the notion that, if employees find no remedy in Title VII, state law provides another access point to justice. In this Note, I seek to challenge the idea that, whereas Title VII can only do so much, state law is there to make up the gap.[122] While some states do have state antidiscrimination laws that are more expansive than federal Title VII, it is not true across the board that state law is an available option for those who are left uncovered by Title VII, especially employees of small firms. This compelling but underexamined facet of antidiscrimination law informs my renewed call for elimination of the small-firm exemption of Title VII.

A. Difficulties of Winning Title VII Claims

Plaintiffs have an extremely difficult time winning Title VII lawsuits. Empirical research has consistently shown that Title VII plaintiffs have lower chances of winning pretrial and at trial than do other civil plaintiffs.[123] Only about 15% of complaints filed with the EEOC result in some form of relief for the plaintiff.[124] And only 3.4% of employment-discrimination cases go to trial.[125] Within those cases that do go to trial, women and minorities have the lowest rates of success.[126] The burden shifting baked into the structure of a disparate-impact Title VII claim only makes it harder for plaintiffs to win. After the plaintiff shows disparate impact, if the defendant can justify its practice, the plaintiff must show discriminatory motive or that the proffered justification is pretextual.[127]

One potential difficulty for the plaintiff who alleges disparate-treatment discrimination at a small firm is the necessity of finding a comparator—that is, someone who is similarly situated to the plaintiff and who has been treated more favorably than the plaintiff.[128] By comparing this similarly situated person to the plaintiff, the thought is, the discrimination against the plaintiff is made more clear.[129] The presence or absence of a comparator may be determinative of whether the court finds that the plaintiff has met the prima facie case or established pretext on rebuttal.[130] When a plaintiff seeks to show discrimination by a small firm, there will be a smaller pool of comparable applicants—and if the court de facto requires this proof in order to find the plaintiff’s case meritorious, the lack of a comparator may be fatal to the plaintiff’s Title VII lawsuit.

Despite the fears that employers will be unfairly targeted and that plaintiffs are winning windfall settlements based on frivolous Title VII claims, the data show that plaintiffs, even when they rarely do win, receive modest settlements or judgments. This counters the notion that Title VII claims are so burdensome to employers that they have the potential to ruin the economy.[131] And employment-discrimination plaintiffs’ claims are overwhelmingly nonfrivolous.[132]

While it is difficult to win a Title VII lawsuit at trial, it is not worthless for the plaintiff to be given the opportunity to file. Discrimination in the workplace is still pervasive, and about one-third of plaintiffs are able to recover a moderately favorable amount through settlement.[133] Furthermore, when the employee threshold was lowered from twenty-five to fifteen, there was a quick and significant improvement in the employment prospects of black workers.[134] Thus, employment prospects of minorities and protected classes will likely benefit from expanded coverage, irrespective of whether their likelihood of winning litigation improves simultaneously. And given the difficulties that face plaintiffs on the merits, the fact that so many workers are precluded from even filing their claim simply by virtue of the number of coworkers that they have compounds the practical unavailability of remedy.

B. Historical Interaction Between State and Federal Antidiscrimination Law

When Title VII was drafted in 1964, it was modeled after existing state employment antidiscrimination law; several of these states already carved out exceptions for small firms.[135] Since then, federal and state antidiscrimination laws have taken cues from one another, evolving in tandem as social pressures increased for different legislators at different times.[136]

Prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, when federal antidiscrimination legislation seemed like a pipe dream, some state legislatures took matters into their own hands and created antidiscrimination laws at the state level.[137] Early state antidiscrimination laws prohibited discrimination on the basis of various classes but many precluded private enforcement.[138] The first attempt to create a fully enforceable antidiscrimination statute at the state level was in Michigan in 1943, though this bill ultimately failed.[139] New York and New Jersey were the first states to pass fair-employment-practices legislation with enforcement powers in 1945, and Massachusetts followed in 1946.[140] After World War II, in response to the need for a more diverse work force during the war, other states began enacting fair employment laws.[141] None of the states that passed antidiscrimination laws prior to 1960 were in the South.[142]

With the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, states faced renewed pressure to adopt employment antidiscrimination statutes, and many did, even in the South.[143] There is not a definitive consensus on what drives the spread (or “diffusion”) of new laws at the state level, but scholars have identified state wealth, political-party demographics, and diversity of residents as factors that may have affected whether a state adopted civil rights laws earlier or later in the bell curve.[144] However, even from the start, the South was an obvious outlier in the diffusion of antidiscrimination law.[145]

C. Coverage of State Laws in the South

In this subpart, I will examine how state antidiscrimination law does not adequately cover the gap left by Title VII’s small-firm exemption and why the availability of state-law remedies should not be used as a justification for failing to extend coverage of Title VII. For the purposes of this Note, I have limited my analysis to the states in the southern United States. As a practical matter, a comprehensive analysis of all fifty states is beyond the scope of this Note. I have identified H-2A migrant farmworkers as a group of low-wage workers who are particularly vulnerable to discrimination and often work for Title VII-exempt firms.[146] Given the overlap of numerous seasonal workers and less-robust antidiscrimination law in the South, the South is a particularly salient region in which to study the gap in federal and state employment antidiscrimination law.

For purposes of this Note, I define “the South” to comprise the same sixteen states identified by the U.S. Census Bureau as belonging to the South.[147] All but three states in the U.S. have a generally applicable employment antidiscrimination statute. All three of the states without a generally applicable statute—Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi—are in the South.[148] Across the U.S., thirty-three states have fair-employment statutes that cover employers with fewer than fifteen employees.[149] Of the seventeen states that do not cover employers of fewer than fifteen employees, ten are in the South (including the three states that have no generally applicable statute at all).

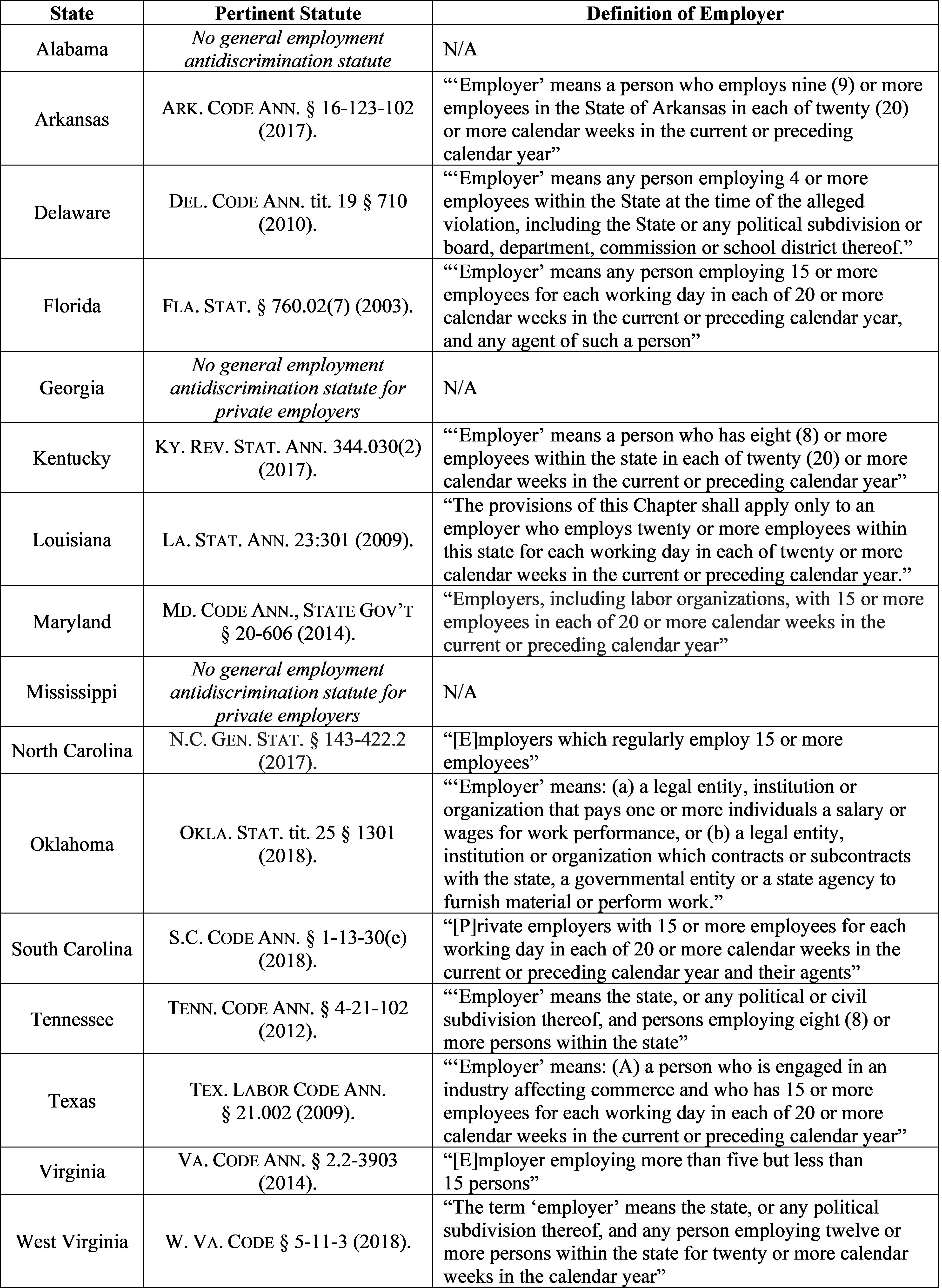

What follows is a chart of the applicable definitions of “employer” in state antidiscrimination statutes in the South.[150] I have isolated this portion of state statutes because the definition of “employer” is often the site of any small-firm exemption, as this tells who is covered by the law and who is not. Of interest is that, while the South as a region tends to have less coverage than Title VII, some states do cover employers with significantly fewer than fifteen employees.[151] Nonetheless, in ten of the sixteen surveyed states, employers exempt from Title VII are also exempt from state law.[152] In the South especially, state law cannot be counted on to provide a remedy to plaintiffs not eligible for relief under Title VII.[153]

Table 1: State Antidiscrimination Law Employee Thresholds

IV. Farmworkers in the South: A Case Study

Specifically, I now look at the example of H-2A migrant farmworkers in the South, and present the special vulnerabilities and lack of remedies available to migrant farmworkers facing discrimination. These factors provide another reason why current state laws in the South are not sufficient to make up the gap left by Title VII and why the small-firm exemption to Title VII is unacceptable.

A. Many Vulnerable Workers Are Left Without Remedy

The H-2A temporary-agricultural-worker program allows farm owners (growers) to hire foreign agricultural workers on temporary seasonal visas upon a showing that no U.S. workers are available to fill the job.[154] While temporary visas to work in the U.S. are an appealing form of entry into the U.S. job market for many workers,[155] the structure of the program leaves workers isolated and vulnerable to abuses such as dilapidated housing, illegally low wages, and even forced labor.[156] Because of the structure in which the visa is sponsored by the grower, H-2A workers (except in rare circumstances) cannot leave their jobs without also having to leave the U.S., forcing many workers to withstand horrible conditions for the sake of economic need.[157]

Relevant to this Note is the way in which H-2A migrant farmworkers are especially vulnerable to discrimination in the workplace, including racial and sex-based discrimination.[158] However, farmworkers at smaller farms may not bring a claim under Title VII. The South African worker who is fired following a string of pointed xenophobic comments does not have a Title VII claim if there are only five people on the farm. The Guatemalan woman who is not hired to pick blueberries this year because the grower hires only men has no Title VII claim if only ten workers are on the farm. The gay tomato packer from Mexico who is sexually assaulted by the foreman at work has no Title VII claim if there are only fourteen workers this year.

This is particularly troublesome when we remember that on the Senate floor, excluding seasonal workers (many of whom work in agriculture) was one of the reasons discussed for adding a minimum-employee threshold.[159] I posit that the intentional exclusion of seasonal agricultural workers from Title VII, as well as the exclusion of agricultural workers from other employment-law protections (e.g., NLRA collective bargaining, FLSA overtime provision)[160] emboldened states with agriculture-driven economies to carve out employment-discrimination exemptions to benefit small growers in state law as well.

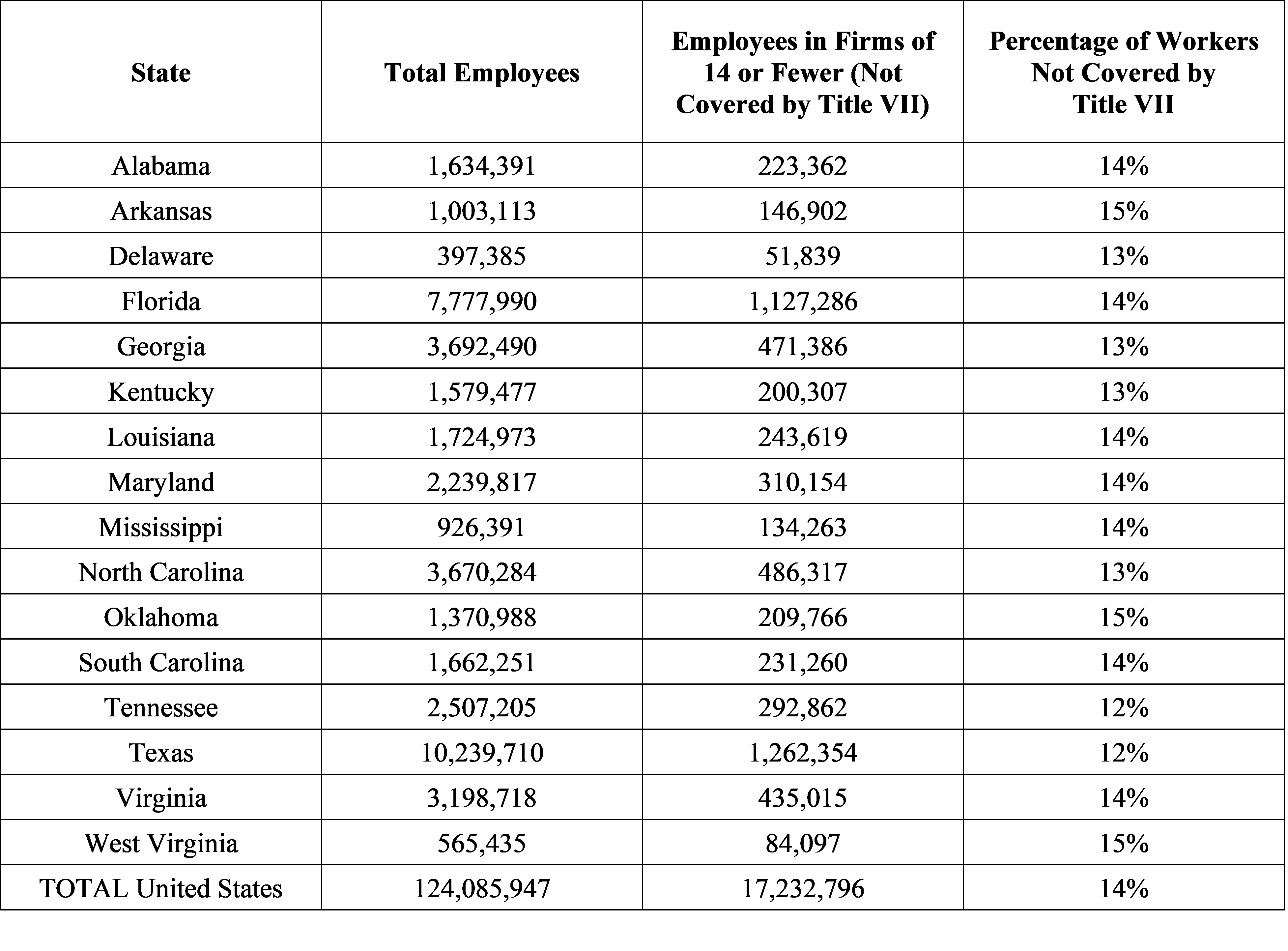

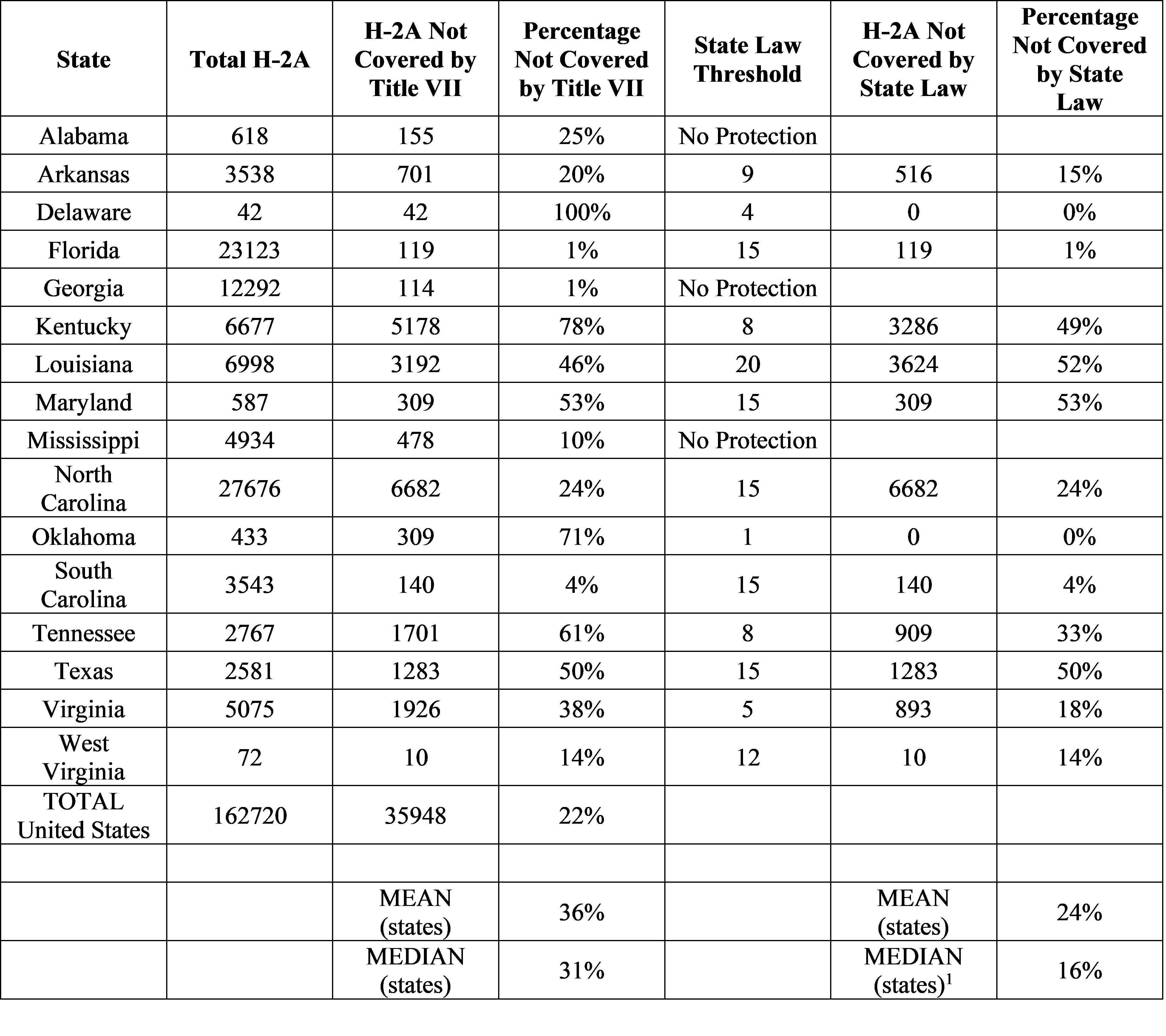

As shown in the tables below, farmworkers are left uncovered by antidiscrimination law at a higher rate than the total U.S. workforce at both the state and national levels. This demonstrates that, in at least one setting, the already-unsettling statistic of workers who are unable to file Title VII complaints nationwide is misleadingly low.

Across all industries in the U.S., Title VII pretty consistently excludes about 14% of the workforce from its protections, and this is no different within the states in the South.[161] But when “H-2A migrant farmworkers” as a group are isolated, the numbers shift. At the national level, 22% of H-2A farmworkers are left uncovered by Title VII.[162] In the South, the median percentage of H-2A workers not covered by Title VII is much higher, at 31%.[163] Even though some states in the South have lower minimum-employee thresholds, a median 16% of H-2A farmworkers are not covered by state law either, which is still higher than the national all-industry Title VII noncoverage rate of 14%.[164]

Earlier in this Note, I reviewed the literature critiquing the small-firm exemption to Title VII and the way that many important workers are left uncovered. The data I have collected provides a compelling example of a particularly vulnerable group of workers harmed by the gap between federal and state antidiscrimination-law thresholds. At least in the South, and at least concerning H-2A farmworkers, even more expansive state-law thresholds are not adequately covering workers who are left uncovered by Title VII. While state law does cover greater numbers of farmworkers in the South than does Title VII, it is clear that this vulnerable group of workers continues to be left more vulnerable to employment discrimination than workers in other industries simply by virtue of the size of the farm they work on.

Table 2: Entire U.S. Workforce by Firm Size, Across All Industries, 2015[165]

Table 3: H-2A Farmworkers by Farm Size, 2015[166]

1This median eliminates Louisiana, whose pertinent statute is less expansive than Title VII and creates a misleading percentage of workers who are not covered by state law, given that some of those workers are still covered by Title VII. When Louisiana is added to this median, the figure becomes 18%.

B. State-Law Solutions Are Insufficient

Upon concluding that the small-firm exemption to Title VII is problematic and creates an unjustifiable gap in coverage, it is tempting to turn to state laws—either as an existing secondary source of remedies or as a solution for closing the gap. In this subpart, I seek to demonstrate that reliance on state law and initiatives to change state law in the South are not realistic or fully desirable alternatives to eliminating the small-firm exemption at the federal level. While pressuring state lawmakers to change policy at a state level may be one part of the strategic puzzle, advocates should continue to seek elimination of the small-firm exemption to Title VII.

1. Current State Laws Are Inadequate.—The existence of antidiscrimination law at the state level is theoretically better than its nonexistence. But state enforcement agencies may face long backlogs,[167] have limited jurisdiction or budgets,[168] or have less expansive remedies available.[169] To be sure, the creative advocate may find a cause of action at the state level that provides the client with a remedy. And in some cases, due to the ideological makeup of the pertinent federal district court or the applicable procedural rules, state court may be a preferable forum even when state antidiscrimination law provides the same or less coverage as Title VII. In other instances, a well-structured state common law contract or tort claim may suffice.[170] A common law contract or tort claim may have added benefits, such as opening the door for punitive or emotional distress damages, the option of a jury trial, or not having to prove discriminatory intent, only intentional action.[171]

However, the existence of these fallback causes of action should not be used as a justification of the small-firm exemption to Title VII, for these causes of action are less desirable than antidiscrimination law in important ways. For example, if attorneys’ fees are not available under the common law claim, aggrieved plaintiffs may struggle to find representation.[172] There is also a dignity (and perhaps retributive) interest in being able to label the wrong that one has experienced as “discrimination” recognized under law rather than as just a contract violation.

Concerningly, the existence of a small-firm exemption in the federal statute sometimes gets used as a policy argument against tort liability for small firms in the employment-law setting.[173] Some contract claims are considered “waivable” and may have been inadvertently waived before the plaintiff talked to an attorney.[174] Finally, common law claims may vary by state and cannot be counted on uniformly. For example, in Arkansas, if a farmworker works on a farm of eight employees, the grower is exempt from Title VII as well as state antidiscrimination law—and further, there are some torts that Arkansas doesn’t recognize, like negligent infliction of emotional distress.[175]

2. Expanding State Law Is an Unrealistic Solution in the South.—Neither should advocates wait for states to eliminate these employee-threshold requirements without also targeting federal law. Because it is unlikely that southern states will adopt laws that are more expansive than federal law, farmworkers in the South may continue to be without remedy until federal law changes. Daniel Lewallen, in his 2014 piece, acknowledges many of the same shortcomings of Title VII that I have mentioned above, focusing especially on the lack of remedy available to employees of small firms and underlining the reasons why these employees are especially vulnerable to discrimination in the workplace.[176] Lewallen then argues that the federal government should economically incentivize states to eliminate their minimum-employee thresholds because states have historically adopted earlier and more-expansive antidiscrimination laws than the federal government, states are not bound by Commerce Clause concerns, and state remedies would avoid burdening the EEOC.[177]

Given my above analysis of state antidiscrimination law in the South, however, this approach is unrealistic as applied to the South. Historically, the states in the South have not passed revolutionary or expansive civil rights laws until they were all but forced to do so.[178] The South is home to some of the most conservative states, where conservatism is defined to signify less government regulation “to promote equality and protect collective goods.”[179] And while the entirety of the United States has shifted to be slightly more liberal over time, most states have remained stable in relative terms.[180] A trend of political conservatism in the South means, for example, that southern states have had fewer civil rights and welfare laws.[181] With the exception of Delaware and Maryland, all of the states in the South are currently controlled by the Republican Party[182] and, if diffusion studies hold true, are less likely to pass innovative (i.e., more-expansive) antidiscrimination law.

Today, the South provides drastically less coverage as a region than the nation does as a whole.[183] Because of the persistent lack of remedies at a statutory and common law level for workers such as migrant farmworkers, and the extent to which independent state legislation has led to a regional trend of drastically less coverage in the South, continuing to rely on federalism in the way that Lewallen suggests will not likely lead to any significant changes to state antidiscrimination law in the South.[184]

Since January of 2019, the House of Representatives is now controlled by Democrats, but the Senate still has a Republican majority.[185] Polarization between the major political parties is strong, and it seems difficult to imagine that, even if the Democrats in Congress approved an amendment to Title VII that would lower or eliminate the small-firm exemption, the Republican-controlled Senate would even consider the measure. However, certain modes of framing such a change could make it more palatable to conservative lawmakers.

For example, advocates of lowering the threshold could remind lawmakers that other employment-related legislative schemes (such as OSHA) have no threshold, while IRCA has a four-person threshold and FLSA has a revenue threshold.[186] Neither does Section 1981 exempt small firms.[187] Advocates could then argue that there is an interest in having various schemes be consistent and transparent so that workers and employers know whether they are covered or not. Or perhaps advocates could remind lawmakers that the success rate of Title VII claims is very low, and the burdens placed upon small employers and the EEOC will probably not be realized as often as feared.[188] Another option is to advocate for a reduction of the threshold from fifteen to five rather than a full elimination. A bill reducing the threshold to employers of one or more employees was introduced into the House of Representatives on April 9, 2019,[189] but I am doubtful the 116th Congress will adopt such a measure; for this reason, Lewallen’s suggestion for expanded antidiscrimination protections may be strategic. But there is a certain dignity interest in being able to file a Title VII claim, so even if state-level advocacy is the most realistic short-term strategy in certain left-leaning states, perhaps the Democratic-controlled 116th House of Representatives might lay the groundwork with bills that a future Senate will pass.

Conclusion

This Note has explored a compelling new argument for eliminating or reducing the small-firm exemption to Title VII. The origins of the exemption, along with contemporary arguments for its continued effect, reveal rationales whose logic breaks down upon deeper review. Given that the stated goal of Title VII is to eliminate widespread discrimination in the workplace, and that small-firm employers are equally guilty of, if not more culpable for, social ills including workplace discrimination, they should not be exempted from antidiscrimination law.

Current state laws do not adequately cover those employees who do not have protection under Title VII, and an isolated look at the population of H-2A migrant farmworkers in the South reveals that this group is especially vulnerable to abuses but covered at a distressingly low rate. The particular vulnerabilities of H-2A migrant farmworkers demonstrate why they need an antidiscrimination remedy. While targeting state lawmakers to change state laws is one idea for how to address the coverage gap left by Title VII, history suggests that this approach alone will not lead to coverage for vulnerable workers in the South, and continued pressure must be placed on legislators at the national level as well.

- .Richard Carlson, The Small Firm Exemption and the Single Employer Doctrine in Employment Discrimination Law, 80 St. John’s L. Rev. 1197, 1197 (2006). ↑

- .42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a)(1) (2012). ↑

- .42 U.S.C. 2000e(b) (2012). In April 2019, a bill was introduced into the House of Representatives, H.R. 2148, that would change the word “fifteen” to “one.” H.R. 2148, 116th Cong. (2019). ↑

- .See, e.g., Arbaugh v. Y & H Corp., 546 U.S. 500, 504 (2006) (holding that the fifteen-employee threshold is an element of a Title VII claim, not a question of federal subject-matter jurisdiction); Carlson, supra note 1, at 1209 (explaining the effect that this exemption has on business entities that cannot easily be classified by size); Jacqueline Louise Williams, Note, The Flimsy Yardstick: How Many Employees Does It Take to Defeat a Title VII Discrimination Claim?, 18 Cardozo L. Rev. 221, 240, 249 (1996) (comparing different methods for “counting” employees and the inequities in each method). ↑

- .See, e.g., Pam Jenoff, As Equal as Others? Rethinking Access to Antidiscrimination Law, 81 U. Cin. L. Rev. 85, 120 (2012) (arguing that “the EEOC should be reconceived as a tool to broaden access to anti-discrimination law”); Daniel Lewallen, Follow the Leader: Why All States Should Remove Minimum Employee Thresholds in Antidiscrimination Statutes, 47 Ind. L. Rev. 817, 837 (2014) (proposing that the federal government incentivize state-level employment protections); Williams, supra note 4, at 261 (supporting an outright elimination of the fifteen-employee threshold). ↑

- .For an excellent and succinct recap on the history of the small-firm exemption to Title VII, see David C. Butow, Counting Your Employees for Purposes of Title VII: It’s Not as Easy as One, Two, Three, 53 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 1103, 1109–17 (1996). ↑

- .Landmark Legislation: The Civil Rights Act of 1964, U.S. Senate, https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/CivilRightsAct1964.htm [https://perma.cc/ZES4-7L43]. ↑

- .Id.; Herbert Hill, The Equal Employment Opportunity Acts of 1964 and 1972: A Critical Analysis of the Legislative History and Administration of the Law, 2 Indus. Rel. L.J. 1, 2 (1977). ↑

- .Charles Whalen & Barbara Whalen, The Longest Debate 95 (1985). ↑

- .Id. at 95, 130, 142; Robert Mann, The Walls of Jericho: Lyndon Johnson, Hubert Humphrey, Richard Russell, and the Struggle for Civil Rights 411 (1996). ↑

- .Mann, supra note10, at 410. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .H.R. 405, 88th Cong., at 3 (1963); Cong. Research Serv., Equal Employment Opportunity: Legislative History and Analysis of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, at 4 (1965); cf. 109 Cong. Rec. 11252 (1963) (statement of Mr. Celler) (containing no definition of “employer”). ↑

- .Compare 109 Cong. Rec. 11252 (1963) with H.R. 7152, 88th Cong. (as reported in House, Nov. 21, 1963) (including a definition of “employer” in the later bill). See also 110 Cong. Rec. 7198, 7208, 7212 (1964) (describing H.R. 7152 as it was first read in the Senate). ↑

- .See generally Cong. Research Serv., supra note 13 (focusing on the structure and formation of the EEOC in the second half of the report). ↑

- .110 Cong. Rec. 16001 (1964). ↑

- .110 Cong. Rec. 7216 (1964) (“Who is an employer within the meaning of Title VII? . . . Can an employer readily ascertain from the language of the bill whether or not he is included? Employers with a large number of employees will have no difficulty, but what about a small businessman?”). ↑

- .Id. at 7216–17. ↑

- .Id. at 7216. ↑

- .Id. at 13087; see also Hill, supra note 8, at 4 (quoting a report by conservative congressmen that said, “If this bill is enacted the farmer (regardless of the number of his employees) would be required to hire people of all races, without preference for any race”). ↑

- .While I focus this Note on the minimum-employee threshold and the ways in which it excludes large groups of workers, further research on which workers are excluded by the twenty-week condition would provide interesting insight as to whether changing that portion of the law would address some of the problems I describe below. ↑

- .Whalen & Whalen, supra note 9, at 191. ↑

- .110 Cong. Rec. 13085 (1964). ↑

- .Id. at 13086. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .See id. at 13087 (“[I]f the proposed legislation would not necessitate going into small business establishments and putting the heavy hand of the Federal Government on the employers, why is such power desired?”). ↑

- .Id. at 13090. ↑

- .See infra Part II. ↑

- .110 Cong. Rec. 13087 (1964). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 13088–89 (including statements by Senators Humphrey and Clark arguing that a 100-employee threshold would cause the bill to lose effectiveness and lead to only 2% of employers being bound). ↑

- .Id. at 13090. ↑

- .Id. at 13091. ↑

- .Id. at 13088. ↑

- .Id. at 13088, 13091. ↑

- .Id. at 13093. ↑

- .Cong. Research Serv., supra note 13, at 7–8. ↑

- .Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. No. 88-352 § 701(b), 78 Stat. 241, 253–54. ↑

- .110 Cong. Rec. 13090 (1964). ↑

- .Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L. No. 92-261 § 2(b), 86 Stat. 103, 103. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .H.R. 8998, 89th Cong. (1965). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .H.R. 10065, 89th Cong. (1965); Paul Downing, Cong. Research Serv., The Equal Employment Act of 1972: Legislative History 2 (1972). ↑

- .E.g., H.R. 17555, 91st Cong. (1970); H.R. 13517, 91st Cong. (1969); H.R. 6228, 91st Cong. (1969); S. 2806, 91st Cong. (1969); S. 2453, 91st Cong. (1969). ↑

- .See Downing, supra note 46, at 25 (describing the introduction of the bill). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Equal Employment Opportunity Enforcement Procedures: Hearings on H.R. 1746 Before the Gen. Subcomm. on Labor of the Comm. on Educ. and Labor, 92d Cong. 422 (1971) (statement of Robert Nystrom, representing Motorola, Inc.). ↑

- .Id. At this hearing, other supporters of the bill included the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Representative Shirley Chisolm, the League of Women Voters (noting that the expansion would cover 9.5 million more workers than the present version), and the National Federation of Business and Professional Women. Id. at 104, 293, 302, 469. ↑

- .Id. at 179. ↑

- .H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, at 20 (1971). ↑

- .Note that a similar bill, S. 2617, was introduced but ultimately overshadowed by the earlier S. 2515. See Downing, supra note 46, at 62, 77 (noting some of the differences between the two bills and describing S. 2515’s eventual passage). Some amendments were made to S. 2515 that were influenced by S. 2617. Id. at 62. ↑

- .Id. at 69–70. ↑

- .Id. at 70. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 71. ↑

- .Id. at 84. ↑

- .C. Steven Bradford, Does Size Matter? An Economic Analysis of Small Business Exemptions from Regulation, 8 J. Small Emerging Bus. L. 1, 4 (2004). ↑

- .See Jenoff, supra note 5, at 95–105 (countering common justifications made in favor of the small-firm exemption); Richard J. Pierce, Jr., Small Is Not Beautiful: The Case Against Special Regulatory Treatment of Small Firms, 50 Admin. L. Rev. 537, 557 (1998) (positing that small firms are responsible for a disproportionate quantity of “social bads that we attempt to reduce through regulation”). ↑

- .Several circuit court cases also discuss this rationale favorably. See Papa v. Katy Indus., 166 F.3d 937, 940 (7th Cir. 1999) (stating that the purpose of small-firm exemptions is to “spare very small firms from the potentially crushing expense of mastering the intricacies of the antidiscrimination laws, establishing procedures to assure compliance, and defending against suits when efforts at compliance fail”); Tomka v. Seiler Corp., 66 F.3d 1295, 1314 (2d Cir. 1995) (“[T]he costs associated with defending against discrimination claims was a factor in the decision to implement a minimum employee requirement.”); Miller v. Maxwell’s Int’l, Inc., 991 F.2d 583, 587 (9th Cir. 1993) (observing that the minimum-employee threshold exists “in part because Congress did not want to burden small entities with the costs associated with litigating discrimination claims”). ↑

- .Jenoff, supra note 5, at 96–97. ↑

- .Id. at 98. ↑

- .Carlson, supra note 1, at 1247. ↑

- .Id. at 1249. ↑

- .Bradford, supra note 61, at 23. ↑

- .Id. at 25. ↑

- .Pierce, supra note 62, at 549. ↑

- .Id. at 546. ↑

- .Jenoff, supra note 5, at 97 (“[J]udgments in employment discrimination lawsuits are relatively modest compared to other areas of litigation.”). See also infra subpart III(A) for a discussion of how difficult it is for plaintiffs to win Title VII suits. ↑

- .H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, at 20 (1971). ↑

- .S. Rep. No. 88-867, at 1 (1964). ↑

- .See 110 Cong. Rec. 13087 (1964) (including remarks by Senator Dirksen that moving the threshold to cover only 100-employee firms would eviscerate its purpose). ↑

- .Jenoff, supra note 5, at 101. Recall that Senator Humphrey made this same argument in debate about Title VII. 110 Cong. Rec. 13090–91 (1964). But see Carlson, supra note 1, at 1250 (arguing that the schemes are different because the effects of violating OSHA or environmental regulations could have wide-ranging consequences, while the effects of violating Title VII are “contained” to the individuals being discriminated against). ↑

- .Carlson, supra note 1, at 1204. ↑

- .8 U.S.C. § 1324b (2012). ↑

- .Jenoff, supra note 5, at 100. ↑

- .But see Carlson, supra note 1, at 1204–05 (arguing that counting heads is more predictable than counting revenue and consistency may be desirable). ↑

- .See also 110 Cong. Rec. 13089 (1964) (including comments by Senator Clark that he might agree to a five-person threshold because he recognizes that there are costs for employers involved in having a complaint filed against them). ↑

- .Jenoff, supra note 5, at 101–02. ↑

- .See 110 Cong. Rec. 13086 (1964) (expressing concern for mom-and-pop stores and arguing that they should be able to choose for themselves whom they hire); Jenoff, supra note 5, at 102 n.71 (“[I]n debating whether the minimum employees threshold should have lowered from twenty-five to eight in the context of the proposed 1971 amendments to Title VII, some legislators argued that these businesses, often family-run, would likely hire the friends and relatives or those of the same ethnicity of the owner.”). ↑

- .See Jenoff, supra note 5, at 101 (“[A] second justification often articulated in favor of the small business exemption is that small employers need to rely on personal relationships in hiring and other employment decisions . . . .”). ↑

- .Carlson, supra note 1, at 1261. ↑

- .Id. at 1262. Particularly ironic about this point is that the government in 1964 did restrict whom you could choose as your wife—Loving v. Virginia, 338 U.S. 1 (1967), was not decided until 1967 and Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584 (2015), was not until 2015. An analogous argument arose in the realm of housing discrimination as the “Mrs. Murphy debate”—if an individual woman (Mrs. Murphy) wants to let out a room in her house, can the government regulate whom she lets it to? Carlson, supra note 1, at 1261. ↑

- .Jenoff, supra note 5, at 102. ↑

- .Id. at 102–03. ↑

- .See id. at 103 (“Small business is not sacrosanct and should not enjoy unfettered latitude to discriminate in its personnel decisions. Rather, it should be subject to the anti-discrimination mandate in a manner that takes into account the unique concerns of the small firm.”). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. The concern for the “flood of litigation” at the federal level is central, too, to Lewallen’s proposal for incentivized changes to state laws. Lewallen, supra note 5, at 832. ↑

- .Jenoff, supra note 5, at 103. ↑

- .Id. at 103–04. ↑

- .See Carlson, supra note 1, at 1268 (describing the EEOC as “an agency of limited size” meant to “target cases yielding the greatest impact”). ↑

- .See id. (describing the impracticality of an EEOC capable of effectively handling every claim). ↑

- .Jenoff, supra note 5, at 104. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Carlson, supra note 1, at 1264. ↑

- .See id. (“Self-employment and ownership of small business provides employment and opportunity for many persons who find it difficult . . . to conform to rules established by others.”). ↑

- .Id. Note that inherent to this claim is the assumption that small employers are still subject to tort liability. ↑

- .Id. at 1266–67. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .See id., at 1266 (noting that although minority entrepreneurship was one rationale behind the small-firm exemption, African-American small business ownership trails that of white Americans); see also Pierce, supra note 62, at 545 (“Thus, it is safe to predict that special preferences for disadvantaged individuals and firms will increase significantly as special preferences for racial minorities and minority-owned firms disappear. Indeed, this process of displacement is already underway.”). ↑

- .Pierce, supra note 62, at 553. ↑

- .Id. at 551. ↑

- .Id. at 553, 556. ↑

- .Id. at 554. ↑

- .Carlson, supra note 1, at 1269–70. ↑

- .See supra note 10 and accompanying text. ↑

- .Carlson, supra note 1, at 1269–70. ↑

- .Id. at 1270. ↑

- .Id. at 1269. ↑

- .Pierce, supra note 62, at 561. ↑

- .Harry T. Holzer, Why Do Small Establishments Hire Fewer Blacks Than Large Ones?, 33 J. Hum. Resources 896, 900–01 (1998). Consistent results have been found in other studies. See Pierce, supra note 62, at 558 n.99 (listing numerous studies and articles discussing the low number of black workers being hired by small firms compared to large firms). ↑

- .Holzer, supra note 114, at 901, 903. ↑

- .Id. at 901, 903, 907. ↑

- .Id. at 907. ↑

- .Lewallen, supra note 5, at 827. The inability to seek support and remedy in jobs where there is no human resources department has been especially illuminated by the #MeToo movement of the past year. See Andrea Johnson et al., Nat’l Women’s Law Ctr., #MeToo One Year Later: Progress in Catalyzing Change to End Workplace Harassment 1–2, 5 (2018), https://nwlc-ciw49tixgw5lbab.stackpathdns.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/MeToo-Factsheet-2.pdf [https://perma.cc/26KK-YJUD] (explaining some state-level wins since the beginning of the movement and explaining the need for further expansion and strengthening of antidiscrimination laws at all levels of government so that technicalities in the definitions of “employee” and “employer” do not leave people unprotected). ↑

- .Lewallen, supra note 5, at 828. ↑

- .Pierce, supra note 62, at 557–60. ↑

- .See id. at 561 (“Obviously, formal special regulatory treatment of small firms helps to explain why small firms account for a massively disproportionate quantity of the social bads that regulation attempts to reduce.”). ↑

- .See, e.g., Lewallen, supra note 5, at 834 (identifying many of the abovementioned problems with the small-firm exemption but suggesting that change at the state level is the best solution); Sarah E. Wald, Alternatives to Title VII: State Statutory and Common-Law Remedies for Employment Discrimination, 5 Harv. Women’s L.J. 35, 38, 72 (1982) (arguing that state law may provide a more adequate or preferable remedy than Title VII). ↑

- .Minna J. Kotkin, Outing Outcomes: An Empirical Study of Confidential Employment Discrimination Settlements, 64 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 111, 115 n.14 (2007). ↑

- .Michael Selmi, Why Are Employment Discrimination Cases So Hard to Win?, 61 La. L. Rev. 555, 558 (2001). ↑

- .Kotkin, supra note 123, at 112. ↑

- .David Benjamin Oppenheimer, Verdicts Matter: An Empirical Study of California Employment Discrimination and Wrongful Discharge Jury Verdicts Reveals Low Success Rates for Women and Minorities, 37 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 511, 516 (2003); see also Wendy Parker, Lessons in Losing: Race Discrimination in Employment, 81 Notre Dame L. Rev. 889, 894 (2006) (“[Employment discrimination] plaintiffs almost always lose when courts resolve their claims.”). ↑

- .St. Mary’s Honor Ctr. v. Hicks, 509 U.S. 502, 506–08 (1993); Barbara J. Fick, Pretext or Pretext-Plus: What Must a Plaintiff Prove to Win a Title VII Lawsuit?, 1992–93 Term Preview U.S. Sup. Ct. Cas. 356, 357 (2013). ↑

- .Charles A. Sullivan, The Phoenix from the Ash: Proving Discrimination by Comparators, 60 Ala. L. Rev. 191, 193 (2009). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 194. ↑

- .Kotkin, supra note 123, at 144. ↑

- .Id. at 115, 117. ↑

- .Id. at 157. ↑

- .Kenneth Y. Chay, The Impact of Federal Civil Rights Policy on Black Economic Progress: Evidence from the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, 51 Indus. & Lab. Rel. Rev. 608, 631 (1998). ↑

- .Carlson, supra note 1, at 1204–05; see also 110 Cong. Rec. 13087–88 (1964) (including statements by Senator Humphrey demonstrating concern about leaving a gap between state and federal law). ↑

- .Duane Lockard, Toward Equal Opportunity 13 (Paul Y. Hammond & Nelson W. Polsby eds., 1968); see also David Freeman Engstrom, The Lost Origins of American Fair Employment Law: Regulatory Choice and the Making of Modern Civil Rights, 1943-1972, 63 Stan. L. Rev. 1071, 1073–74 (2011) (describing how Title VII was drafted to mirror some features of existing state legislation, and states followed the lead when the federal government created a Fair Employment Practices Commission). ↑

- .Engstrom, supra note 136, at 1079. However, not all state courts were favorable to this new legislation, and even in states with antidiscrimination laws, courts did not always enforce the laws robustly. Id. at 1095; see also Ronald A. Krauss, Am. Jewish Cong., State Civil Rights Agencies: The Unfulfilled Promise 2 (1986) (describing how state antidiscrimination agencies had huge administrative backlogs, even in the 1960s). ↑

- .Engstrom, supra note 136, at 1080–81. ↑

- .Id. at 1072–73. ↑

- .Lockard, supra note 136, at 24 tbl.II. ↑

- .Krauss, supra note 137, at 5. ↑

- .See Lockard, supra note 136, at 24 tbl.II (including a chart of state laws by year). ↑

- .Krauss, supra note 137, at 18 (“[I]t created a societal pressure for action which overcame many states’ prior reluctance to enact, or vigorously enforce, state anti-discrimination laws.”). ↑

- .E.g., Virginia Gray, Innovation in the States: A Diffusion Study, 67 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 1174, 1184 (1973); Anthony S. Chen, The Passage of State Fair Employment Legislation, 1945-1964: An Event-History Analysis with Time-Varying and Time-Constraint Covariates 8–13 (Inst. of Indus. Relations, Working Paper No. 79, 2001). ↑

- .William J. Collins, The Political Economy of Race, 1940-1964: The Adoption of State-Level Fair Employment Legislation 4 (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Research, Historical Paper 128, 2000). ↑

- .See supra subpart III(A). ↑

- .Census Bureau Regions and Divisions of the United States, U.S. Census Bureau (2010), https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf [https://perma.cc/L33V-S5CL]. Many different people have many different understandings of what defines the South and which states are part of the South. With recognition that defining the South could be an article of its own, I will defer to the designations of the U.S. Census Bureau for this Note. I have eliminated the District of Columbia from my analysis, given that it does not have state law and is not identified as a category in either Census Bureau or Department of Labor statistics regarding employment. ↑

- .See generally Nat’l Conference of State Legislatures, State Employment-Related Discrimination Statutes 1, 4, 9 (2015), http://www.ncsl.org/documents/employ/Discrimination-Chart-2015.pdf [https://perma.cc/W7CJ-F222] (surveying all fifty states’ laws in this area). ↑

- .Wald, supra note 122, at 42. ↑

- .Some states have other laws against sex, age, or disability discrimination, but in states with more than one statute in the spirit of antidiscrimination, I have selected the one that most closely resembles Title VII; usually this is the statute that names classes such as race, ethnicity, and sex. ↑

- .See infra Table 1. ↑

- .See infra Table 1. ↑

- .For further discussion on this point, see supra subpart II(B). ↑

- .H-2A Temporary Agricultural Program, U.S. Dep’t of Lab. (Oct. 22, 2009), https://www.foreignlaborcert.doleta.gov/h-2a.cfm [https://perma.cc/CQ5P-3JUS]. ↑

- .See Farmworker Justice, No Way to Treat a Guest: Why the H-2A Agricultural Visa Program Fails U.S. and Foreign Workers 10, https://www.farmworkerjustice.org/sites/default/files/documents/7.2.a.6%20fwj.pdf [https://perma.cc/2ELQ-VNXK] (arguing that workers expect to work at jobs for which American workers are unavailable, in addition to livable housing, safe working conditions, and wages that allow them to feed themselves and their families). ↑

- .Id. at 13–16. ↑

- .See Dan Charles, Government Confirms a Surge in Foreign Guest Workers on U.S. Farms, NPR: The Salt (May 18, 2017, 2:59 PM), https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/05/18/528948143/government-confirms-a-surge-in-foreign-guest-workers-on-u-s-farms [https://perma.cc/Z67K-Z356] (“Temporary workers also have limited rights; they cannot leave their jobs or switch employers, and critics say it leaves them vulnerable to abuse or mistreatment.”). ↑

- .Farmworker Justice, supra note 155, at 26–27; see Press Release, U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, Koch Foods Settles EEOC Harassment, National Origin and Race Bias Suit (Aug. 1, 2018), https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/newsroom/release/8-1-18b.cfm [https://perma.cc/FH49-8GBS] (describing a lawsuit settlement in a case regarding farmworkers against Koch Foods, alleging, inter alia, sexual harassment). ↑

- .110 Cong. Rec. 13087 (1964). ↑

- .See 29 U.S.C. § 152(3) (2012) (defining “employee” to exclude agricultural workers); 29 U.S.C. § 213 (2012) (stating that overtime pay does not apply to agricultural workers). ↑

- .See infra Table 2. ↑

- .See infra Table 3. ↑

- .See infra Table 3. ↑

- .See infra Table 3. ↑