State Public-Law Litigation in an Age of Polarization

Public-law litigation by state governments plays an increasingly prominent role in American governance. Although public lawsuits by state governments designed to challenge the validity or shape the content of national policy are not new, such suits have increased in number and salience over the last few decades—especially since the tobacco litigation of the late 1990s. Under the Obama and Trump Administrations, such suits have taken on a particularly partisan cast; “red” states have challenged the Affordable Care Act and President Obama’s immigration orders, for example, and “blue” states have challenged President Trump’s travel bans and attempts to roll back prior environmental policies. As a result, longstanding concerns about state litigation as a form of national policymaking that circumvents ordinary lawmaking processes have been joined by new concerns that state litigation reflects and aggravates partisan polarization.

This Article explores the relationship between state litigation and the polarization of American politics. As we explain, our federal system can mitigate the effects of partisan polarization by taking some divisive issues off the national agenda, leaving them to be solved in state jurisdictions where consensus may be more attainable—both because polarization appears to be dampened at the state level and because political preferences are unevenly distributed geographically. State litigation can both help and hinder this dynamic. The available evidence suggests that state attorneys general (who handle the lion’s share of state litigation) are themselves fairly polarized, as are certain categories of state litigation. We map out the different ways states can use litigation to shape national policy, linking each to concerns about polarization. We thus distinguish between “vertical” conflicts, in which states sue to preserve their autonomy to go their own way on divisive issues, and “horizontal” conflicts, in which different groups of states vie for control of national policy. The latter, we think, will tend to aggravate polarization. But we concede—and illustrate—that it will often be difficult to separate out the vertical and horizontal aspects of particular disputes and that in some horizontal disputes the polarization costs of state litigation may be worth paying.

We argue, moreover, that state litigation cannot be understood in a vacuum but must be assessed as part of a broader phenomenon in American law: our reliance on entrepreneurial litigation to develop and enforce public norms. In this context, state attorneys general often play roles similar to “private attorneys general,” such as class action lawyers or public interest organizations. And states, with their built-in systems of democratic accountability and internal checks and balances, compare well with other entrepreneurial enforcement vehicles in a number of respects. Nevertheless, state litigation efforts may not always account well for divergent preferences and interests within the broad publics that the states represent, and this deficiency becomes particularly important in politically polarized times. Although our account of state litigation is, on the whole, a positive one, we caution that state attorneys general face a significant risk of backlash by other political actors, and by courts, if state litigation is (or is perceived to be) a bitterly partisan affair.

Introduction

This Article explores two highly salient phenomena in American politics and seeks to better understand the relationship between them. The first is the advent, largely over the past few decades, of high profile public-law litigation by state attorneys general (AGs) acting on behalf of state governments and citizens—the sort of thing that Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott meant when he described a typical workday as, “I go into the office, I sue the federal government and I go home.”[3] Such cases include red-state challenges to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Obama Administration’s Deferred Action for Parents of Americans program (DAPA), and “blue-state” challenges to the Bush Administration’s environmental policies and the Trump Administration’s travel bans. Yet state AGs’ influence over national policy extends beyond those well-known examples. It also includes significant increases in amicus curiae filings by state governments, multistate litigation by groups of AGs working together to combat questionable business practices,[4] as well as state efforts to enforce federal law in ways that may deviate from the national Executive’s priorities.[5] State AGs are playing a pivotal role in some of the most important national political debates of the day, and they are doing so largely through entrepreneurial litigation.

The second phenomenon is political polarization. Americans are more divided today along partisan and ideological lines than they have been for some time.[6] This polarization has important consequences, rendering national politics unusually contentious and often undermining our capacity for self-governance. It may cause legislative gridlock, prompting unilateral presidential action. At other times, polarization can lead to more extreme national legislation.

State public-law litigation, especially in its most recent manifestations, seems at first glance to be a symptom of the broader polarization in national politics.[7] It is no accident that AG Abbott—a Republican—made his comment about suing the federal government during the Obama Administration. Now that the political tables have turned, the homepage for the Democratic Attorneys General Association reads, in large orange font, “Democratic Attorneys General are the first line of defense against the new administration.”[8] These partisan divides play out across the policy spectrum. For much of the last decade, for example, coalitions of blue states committed to stricter environmental safeguards have litigated to prod the federal Environmental Protection Agency to more stringently regulate emissions of greenhouse gases.[9] Over the same period, red-state coalitions have likewise litigated to prevent such regulation.[10] Similarly, red- and blue-state coalitions confronted one another over the constitutionality of the ACA’s individual mandate and Medicaid expansion.[11] And state amicus curiae filings in the same-sex marriage litigation likewise reflect a passionate red/blue divide over the pace of social change with respect to sexual orientation and family relationships.[12] In many instances, state public-law litigation is a vehicle for expressing the same divisions that convulse American politics generally.

As state litigation has grown in volume and prominence, it has drawn more attention in both the academic literature and the popular press. Much of that attention has been negative.[13] At least since the multistate tobacco litigation of the 1990s, critics have argued that state suits may effectively result in national lawmaking by settlement, coercing defendants and circumventing federal lawmaking processes.[14] But new lines of critique have emerged in more recent years, suggesting links between AG litigation and trends in partisanship and polarization. Critics contend that AGs are abandoning their traditional role “as representatives of their states,” in which the goal of litigation was to vindicate the long-term, institutional interests of states qua states.[15] Rather than focusing on threats to state autonomy, AGs today can be found pushing for more federal regulation[16] or supporting claims “of individuals as opposed to the states themselves.”[17] And, as noted, they often are doing so in partisan clusters rather than banding together as states to promote state interests in a politically neutral manner. James Tierney, a former Maine AG and leading observer on these matters, worries “that the AGs become seen as one more lawyer . . . on the make, and that undercuts the credibility of the office itself.”[18]

We have some sympathy for those critiques, but we think the picture is far more complicated than critics acknowledge—in part because the concept of “state interests” is itself complicated. To understand state litigation, it helps to situate it within broader theories of federalism. When most people think of federalism, they imagine “vertical” conflicts between the states and the federal government, conflicts in which states typically are resisting assertions of federal power so as to maximize their own regulatory autonomy. But our federal system also addresses “horizontal” conflicts in which powerful states (or groups of states) attempt to impose their will on others. Vertical conflicts are, for the most part, about who decides—the states or the federal government. Horizontal conflicts are about what policies will prevail.

From this perspective, the critiques of state litigation are easy to understand. When states challenge federal policy in vertical cases, they are performing their traditional role in a federal system—throwing off the federal yoke so that they can govern themselves. To the extent that state AGs argue in favor of federal law in such cases, they look like traitors to the cause. Horizontal cases, similarly, appear to be at odds with the states’ shared interest in autonomy. When state AGs argue in favor of individual claims of constitutional right, for example, or use federal law to reform widespread business practices, they seem to be vindicating their home states’ regulatory interests—interests that tend to track partisan divisions—at a cost to the broader institutional interests of the states as such.

This contrast between vertical and horizontal conflicts is a helpful frame for considering state public-law litigation. But the line between such conflicts—and between states’ institutional and regulatory interests—is often fuzzy and contested. As we explain, many seemingly vertical conflicts have horizontal aspects and vice versa. For regulatory challenges that cannot be solved without collective action—certain environmental issues, for example—pro-regulatory states have little choice but to push for nationwide solutions. In such circumstances, states’ institutional and regulatory interests merge, and states exercise their sovereignty by appealing to federal power. Things look different to anti-regulatory states, and those disagreements will often play out along partisan lines. It does not follow, however, that the state AGs on either side of the case are putting politics before state interests. Likewise, under our contemporary model of federalism, states have an interest not only in doing their own thing but also in participating in national politics—an interest that may aggravate horizontal conflict.

State litigation must also be viewed in the evolving context of public-law litigation generally in American law. Our legal system is exceptional in its reliance on litigation and courts to resolve conflicts and articulate policies that, in other systems, would fall into political or bureaucratic channels.[19] And rather than rely exclusively on enforcement by the national Executive, federal law frequently authorizes entrepreneurial litigation by private attorneys general. When state AGs enforce federal law, they play a similar entrepreneurial role to class action attorneys or public interest organizations. The same thing is true when state AGs rely on their own state laws but cooperate to secure nationwide judgments or settlements that impose a de facto national regulatory solution on a particular industry.

An important response to criticisms of state litigation, then, is to ask “compared to what?” When states sue to enforce the Clean Air Act or the securities laws, or to challenge the ACA or the Trump travel bans, they are playing a similar role to the Sierra Club, the ACLU, or class action plaintiffs’ lawyers. If states were precluded from bringing such suits, their private analogs would remain. Yet, as we explain, there are good reasons—grounded in democratic accountability and in state governments’ unique institutional perspectives—to prefer state litigation to purely private mechanisms for aggregating diffuse interests.

Part I of this Article offers a sketch of polarization in the federal and state governments, tracing the relationship between polarization, national policymaking, and policy autonomy at the state level. We suggest that state autonomy can sometimes be a “safety valve” for polarized conflict at the national level. Part II then turns to state litigation. It charts the institutional development of state AGs’ offices and the expansion of doctrinal and statutory rights to sue, which have helped state AGs emerge as a particularly powerful group of lawyers. We then map the different sorts of claims that states use to shape national policy.

Part III turns to the relationship between state litigation and polarization. Few scholars have sought to study polarization in the work of state AGs, but the available evidence suggests that state litigation is indeed becoming more “political” in the sense that Democratic and Republican AGs increasingly are pursuing different causes or are lining up on opposite sides of the same cases. The impact on our broader politics, however, will often turn on the nature of a given lawsuit. We use the distinction between vertical and horizontal conflicts as a framework for normative assessment of state public-law litigation in an era of intense political polarization. Finally, we take up the comparative question in Part IV, situating state litigation within the broader phenomenon of public-law litigation as a mode of American governance. Although we think suits by state AGs compare favorably to other mechanisms of aggregate litigation, we warn that overly aggressive state public-law litigation may result in a judicial or political backlash that might undermine the benefits of this valuable institutional mechanism.

I. Polarization and Federalism

Contemporary American politics displays a level of political polarization that, while hardly unprecedented, is significantly greater than anything in recent memory.[20] For decades, American political scientists lamented the lack of clear programmatic differences between the major political parties; that state of affairs, they complained, deprived American voters of a meaningful choice at election time.[21] The present era thus plays out the old adage, “Be careful what you wish for.” (Alternatively, it embodies the Chinese curse: “May you live in interesting times.”) American politics—and the underlying society—finds itself divided between quite different conceptions of the good life, with strong and contrary implications for government regulation, fiscal policy, and individual rights.[22] The temperature of political debate has called into question whether our national political institutions can mediate and resolve these conflicts. And these changes in political climate have affected the weather at the U.S. Supreme Court, influencing both the sorts of cases brought before the Justices and the types of parties that bring them.

For students of American federalism, there is a certain irony to all this. A decade ago, prominent voices in the federalism literature took the position that American federalism is meaningless and unnecessary because American society lacks the kind of basic divisions that make federalism necessary in, say, Canada or Iraq.[23] This line of thought surely represented the conventional wisdom in terms of its basic assumptions, even if not everyone accepted the conclusion that America’s federal structure could safely be junked.[24] Scholars looking to defend federal structures were left searching for glimmers and vestiges of state identity that might sustain autonomous subnational institutions.[25] The question now, by contrast, sometimes seems to be whether Americans can find sufficient common ground to move forward together on common problems.[26] Federalism, we suggest, can help.

A. Polarization in National Politics

The Democratic and Republican Parties are more polarized today than they have been in decades—maybe more than a century, according to some measures.[27] What that means, in part, is that the contemporary Congress is marked by high levels of partisan sorting: Members are more easily sorted by party today than they were in the past.[28] There are fewer conservative Democrats and fewer liberal Republicans.[29] As a result, there is little or no overlap between members of the different parties.[30] Second, and closely related, is the notion of ideological divergence, which refers to the distance between the party medians.[31] That distance today is greater than at any time since the end of Reconstruction.[32]

A vigorous debate exists as to whether this polarization of politicians reflects a broader polarization of the public at large. One group views the public as basically moderate in its views but sees a fundamental disconnect between those views and a highly polarized political class.[33] Another group holds that polarization reaches much further down into the electorate.[34] But even if the public’s policy views remain moderate, surveys reveal high degrees of “affective” polarization.[35] Simply put, Democrats and Republicans don’t like each other very much—much less, it seems, than in the 1980s and 1990s.[36] And this partisan dislike has translated into a polarization of political trust, so that partisans report radically low levels of trust in government when the other party dominates the national government.[37]

Such polarization translates into sharp and sustained disagreement and a refusal to compromise across party lines. Evidence suggests that this effect is most severe when institutions are closely divided, as either party can realistically hope to gain control and neither can afford to give the other a victory.[38] When different parties control the House and Senate, the probable effect is gridlock—an inability to get things done because there’s no common ground for consensus.[39] The same is often true when one party controls both houses of Congress and the other party controls the White House. Unless the dominant party in Congress has a veto-proof majority, the President can block major legislation.

These obstacles can sometimes be overcome by appeals to the public at large. But low levels of political trust make it difficult for a president to go over the heads of partisan opponents in the Congress and appeal to moderates in the other party, as President Reagan was able to do in the 1980s.[40] The consequences are well known: gridlock means that Congress is likely to produce less federal legislation, and the bills that do emerge are likely to be less consequential.[41] Rather than addressing big, contentious questions, a gridlocked Congress will tend to enact symbolic legislation or to leave the critical choices to agencies.[42]

Things look different under unified government, of course. When the same party controls both houses of Congress and the Presidency, it can—in theory at least—accomplish quite a lot.[43] In times of unified government, the consequence of polarization should be more extreme legislation.[44] In that sense, polarization raises the stakes of control of the national government: if one party can win control of both Congress and the Presidency, it can dictate policy on virtually every issue people might care about and need not compromise with the minority party.

It is not obvious that the polarization we have described is a bad thing. After all, as we have already noted, American political scientists at the middle of the twentieth century longed for ideologically pure parties that would offer voters a clear choice; this, they thought, was the key to truly responsible government.[45] To assess whether political polarization is good or bad for the Republic would require its own article (or book), and we cannot offer a rigorous analysis here. Briefly, we would emphasize several specific concerns developed elsewhere in the literature. Some political scientists argue that unified government can produce legislation that is more extreme than many of the majority party’s own constituents would want—and thus inconsistent with the preferences of the majority of voters.[46] Moreover, our separation of powers effectively imposes supermajority requirements on most legislative action; as a result, polarization combined with a close division of the electorate results either in gridlock or diversion of government action into constitutionally dubious channels.[47] Finally, recent literature suggests that contemporary polarization is more “affective” than policy-driven; in other words, Americans have developed a strong dislike for persons on the other political “team” even though the actual policy differences between the parties are often minor.[48] It is hard to see any upside to polarization once it reaches that point. In any event, we sketch these reasons simply to give a sense of our priors. Our argument here must largely presuppose, rather than defend, the proposition that polarization is worrisome and in need of mitigation. Our question is whether federalism—and, in particular, state litigation—is likely to mitigate or exacerbate the polarization that worries us.

B. Polarization and the States

Federalism can operate as an important safety valve in polarized times, lowering the temperature on contentious national policy debates and creating opportunities for policymaking that may be impossible at the national level.[49] In evaluating this claim, it will help to distinguish between polarization within states and polarization among states. Some states, at least, seem to have less polarized politics than we see at the national level. In these states, bipartisan resolutions to divisive issues may well be possible. But even if states have similar political cultures to that at the national level, the distribution of political preferences is geographically uneven. This polarization among states—the now familiar divide between red and blue states—makes it possible to act on divisive issues in ways that avoid the all-or-nothing nature of national solutions.

1. Polarization Within States.—The patterns of polarization that define national politics today are not replicated in all of the states. In Massachusetts, for example, Democrats and Republicans can agree on a generous level of social provision and broadly libertarian social policies,[50] while Texas Republicans and Democrats tend to share a general commitment to a low-tax, small-government model.[51]

Precisely why this is so is difficult to pin down, but the available evidence suggests two (complementary) answers. First, state politicians may themselves be less polarized—in the sense of ideological distance—than their federal counterparts. Second, even if Democrats and Republicans are miles apart ideologically, the unique features of state government may dampen the effects of that distance.

To begin with, it appears that party identity varies across states: it means something different to be a Republican in Massachusetts than it does to be a Republican in Texas. In other words, partisan sorting is not as clear-cut at the state level as it is in Washington, D.C. Whereas there is vanishingly little overlap between the national representatives of the two parties, the picture looks different if one focuses on state legislators. Democrats elected to state office in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas, for example, are in some cases more conservative than Republicans in Delaware, Illinois, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Hawaii, Connecticut, New York, and Massachusetts.[52]

Ideological divergence is also muted—or at least more mixed—at the state level. A leading 2011 study of polarization in state legislatures found that the distance between party medians varied significantly from one state to the next.[53] California boasted the most polarized state legislature, leading a group of fifteen states in which ideological divergence was more pronounced than in Congress. The majority of state legislatures, however, were less polarized than Congress.[54] Similarly, five of the last six governors of Massachusetts—one of the bluest states there is—have been Republicans.[55] Last year, the current governor of the Bay State enjoyed the highest approval ratings in the nation, and several other Republican governors in blue states are similarly popular.[56] One recent analyst concluded that “Republican gubernatorial candidates are . . . able to be more moderate than Republican presidential candidates, and therefore tend to be more ideologically compatible with the Democrat-dominated electorates of blue states.”[57] Republican governors in Democratic states thus seem to do best when they take a moderate line on social issues and maintain significant separation from the national party.[58]

As this last point suggests, an inquiry into polarization in state government should heed, not only the ideological preferences of state officials, but also how those preferences translate into political behavior. Several characteristics of state government suggest that we might expect state politics to reflect less partisan conflict even if state officials are themselves fairly polarized.[59] For example, surveys indicate that state and local governments enjoy considerably higher levels of trust than the federal government. Researchers have been asking survey questions about trust in government for many decades, and trust has recently become central to some scholars of polarization.[60] Those scholars have generally focused on national-level measures of trust. But the survey questions have often included a comparative component that inquires whether citizens repose more trust in state or national institutions. This research concludes that “[c]itizens on average evaluate the performance of the federal government as significantly lower than that of the state and local governments, report less faith in the federal government to ‘do the right thing,’ have significantly lower confidence in the ability of the federal government to solve problems effectively, see the federal government as significantly less responsive than lower levels of government, and nearly 60% see the federal government as the most corrupt level of government.”[61] If polarization scholars are right that higher levels of trust make it more likely that partisans will make “ideological sacrifices” to create bipartisan solutions,[62] then that ought to be more likely at the state level.

Culture may also play a role in mitigating ideological polarization’s effects on state officials. State political cultures may be sufficiently distinctive that the range of partisan disagreement is narrower within them.[63] Daniel Elazar, for example, argued that certain states share a broader commitment to regulation and social provision based on having been originally settled by New England Puritans committed to those values.[64] Consistent with this view, Republican governors in New England have tended to support the more generous social welfare arrangements in those states while pushing fiscal conservatism around the edges.[65] We might further speculate that state political cultures include shared norms of political practice that inhibit the nastier forms of partisanship that entrench polarization.[66]

Or perhaps state and local governments deal with a large number of bread-and-butter issues—e.g., road maintenance, education, and crime control—on which the public may have limited tolerance for partisan posturing that prevents basic needs from being met.[67] We come from North Carolina—deep purple and closely divided. We just had a particularly nasty gubernatorial election and a fractious legislative session. But even in states like ours, pragmatic concerns like fixing potholes and reducing crime may moderate polarization’s effects. Unlike their federal counterparts, state politicians can’t spend all their time grandstanding; state governments have to get certain things done, and a lot of those things aren’t particularly ideological. Balanced budget requirements may further constrain them from the worst kinds of obstruction and kicking the can down the road. Successful Republican blue-state governors, after all, are frequently characterized as “pragmatic,” “non-ideological” managers who tend to decouple their own political fortunes from the national party.[68] Democratic governors in red states are, for now at least, fewer and further between. But the ones we have seem to have pursued a similar approach.[69]

Another important factor may be that (unlike North Carolina) many states are not as closely divided as the national government—they are not purple but consistently red or blue. As we’ve already noted, some research suggests that close divisions increase the incentives for political opportunism, as the minority party may hope to regain the majority if it can prevent the opposition from being successful.[70] In states where the minority is likely to remain in that position, by contrast, minority party-members may seek to have at least some voice through bipartisan cooperation. We might even be seeing some vindication of the Antifederalist notion that republican government—predicated on statesmanlike transcendence of narrow factional interest—is more likely to succeed in smaller communities. It’s hard to know for sure, and the question is ultimately an empirical one on which we presently lack much good evidence. We do have evidence, however, that polarization and its effects are less extreme at the state level.

One significant caveat is in order. A variety of research suggests that levels of polarization and mistrust are in part a function of the issue set that is salient to voters.[71] The comparatively sunny cast of some states’ politics may thus arise from the issues laid before state governments. If we were to devolve certain contentious issues from the national scene to state governments, that might well change the character of state politics. Perhaps habits of cooperation forged in filling potholes might bleed over into debates about transgender rights. But they also might not.

In sum, there are reasons to think that federalism can mitigate the effects of political polarization by offering alternative policymaking venues in which the hope of consensus politics is more plausible. As the next section details, taking divisive questions off the national agenda may moderate the overall polarization problem even if that is not true.

2. Polarization Among States.—The notion of an equally divided nation goes back all the way to the 2000 election.[72] But very few places in America are fifty-fifty in this way: “Geography matters.”[73] Within the states, relatively small differences in the correlation of partisan forces[74] significantly affect political outcomes, painting some state governments completely red and others blue.[75] In those states, even if state-level bipartisanship fails to generate effective policy on divisive issues, unified government might step in to fill the breach.

As of 2015, only nineteen states had divided government.[76] That number declined to eighteen after the 2016 elections, then slipped to seventeen after West Virginia Governor Jim Justice switched to the Republican party.[77] Thus, even those state legislatures with relatively high levels of polarization may be capable of avoiding gridlock and getting things done. In New Jersey, for example, Democrat Phil Murphy’s election as governor has made the Garden State one of eight states under unified Democratic control. “If Murphy has his way,” the Washington Post predicted, “New Jersey will become a proving ground for every liberal policy idea coming into fashion, from legalized marijuana to a $15 minimum wage, from a ‘millionaire’s tax’ to a virtual bill of rights for undocumented immigrants.”[78] Meanwhile, Republican-controlled states have “pursued economic and fiscal strategies built around lower taxes, deeper spending cuts and less regulation” and have adopted policies with respect to labor, education, and social issues that diverge sharply from blue-state strategies.[79]

To be sure, the combination of polarization and unified government can produce less compromise and more extreme policy in state governments, too.[80] But the stakes are lower for statewide, as compared to nationwide, solutions. At the very least, devolving decision-making authority to the states opens up opportunities for policy variation—not only among states, but also between the states and Congress. A flourishing federal system means that Democrats currently out of power in Washington, D.C. don’t just have to give up or focus on rearguard actions at the federal level; they can govern at the state level.[81] Especially when state government is unified, those Democrats can pursue a very different set of policies than those originating on Capitol Hill. The consequence may not be compromise, exactly, but it does offer a way to serve the preferences of people who identify with the minority party in Congress.[82]

A federalism-based modus vivendi is unlikely to satisfy devoted partisans on one side or another of any divisive issue. But as Michael McConnell has explained, “So long as preferences for government policies are unevenly distributed among the various localities, more people can be satisfied by decentralized decision making than by a single national authority.”[83] Moreover, when different jurisdictions can implement (and not simply advocate) their preferences, they can have significant and unexpected effects on the national debate. When the same-sex marriage issue became salient in the mid-1990s, for example, most states used the autonomy that the federal system afforded them to explicitly outlaw the practice. But some states permitted same-sex marriages to go forward, and over time the example of those new families helped bring about one of the most remarkable shifts in public opinion in American history.[84] State-by-state diversity may thus break up rigidly polarized political patterns over time, even if state political cultures are not significantly more warm and fuzzy than the national one.

C. How Federal Polarization Affects Federalism—And How State Litigation Can Help

We’ve argued that states can serve as safety valves for polarized national politics. In order for states to play those roles, however, the federal government must leave them room to maneuver. And there’s the rub: while polarization highlights the benefits of federalism, it also poses a distinct threat to state autonomy.

This point is most obvious under conditions of unified national government. As we explained above, polarization plus unified government is likely to produce more extreme policy. That means more federal overreaching—statutes that trench on state interests or that are more broadly preemptive in scope. Where that is true, states may find they have less space to act, and the benefits outlined above will be lost.

Divided government at the federal level can also hold threats to state autonomy, though the reason is less intuitive. At first blush, polarization plus divided government may seem like a boon for federalism: the less Congress is able to do, the more that’s left for the states.[85] But congressional gridlock may also produce more unilateral action by the federal Executive, in the form of executive orders and guidance, gentle and not-so-gentle nudges directed at agencies, and so on. This dynamic was reflected in President Obama’s “We Can’t Wait” campaign, for example. The campaign started with a speech in which the President said, “[W]e can’t wait for an increasingly dysfunctional Congress to do its job. Where they won’t act, I will.”[86] And it became a yearlong theme in the lead-up to the 2012 election cycle. In one year alone, the President announced more than forty executive actions packaged under the “We Can’t Wait” brand.[87] President Trump has shown few signs of retreating from executive-branch unilateralism, notwithstanding unified Republican control of government; he has used executive orders for (among other things) his controversial travel bans and efforts to strip “sanctuary cities” of federal funding.[88]

From a federalism perspective, there’s a lot not to like about unilateral executive action. Most obviously, it’s easier to do than running formal legislation through two chambers of Congress and the President. Many people believe that state interests are protected in the national political process through the close ties between national and state parties and politicians and the representation of states through their congressional delegations.[89] Others emphasize the many “veto-gates” in Congress that stand in the way of legislation.[90] These are the so-called political and procedural safeguards of federalism. And to the extent that states get protection in the legislative process, one might worry about federal policy being made in a far more streamlined fashion and centered in the executive branch, where states have no special voice.[91] Granted, states may find considerable freedom to shape federal policy in its bureaucratic interstices by proposing innovative ways to implement federal mandates or by dragging their feet on locally unpopular requirements.[92] But despite the practical importance of implementation authority, the leeway afforded is unlikely to be broad enough to accommodate the basic ideological conflicts that often characterize our polarized national debates.

This brings us to an additional way in which states can mitigate the effects of polarization—not through legislation and regulation, but through litigation: states can challenge federal action that arguably goes too far.[93] Anthony Johnstone has observed that “[i]f the primary virtue of federalism in these politically polarized times is the accommodation of diverse policy preferences . . . then attorneys general are uniquely qualified to give voice to those preferences in federalism litigation.”[94] This role is not unique to states, of course—private litigants can bring federalism-based legal challenges as well.[95] As we explain below, however, considerations of expertise, institutional capacity, and democratic accountability suggest that states may be particularly well-situated to spearhead such litigation. Indeed, states have been at the forefront of some of the most consequential challenges to federal policy in recent years, including not only the constitutional challenge to the ACA but also more recent challenges to the Trump Administration’s travel bans.

Those examples are merely the tip of the state-litigation iceberg, but they capture a feature that has drawn significant attention in popular commentary: the states’ challenges to the ACA and the travel bans have been decidedly partisan affairs. The ACA litigation was led by red states; the ongoing travel-ban litigation is dominated by blue states.[96] One might well wonder, therefore, whether in practice state litigation mitigates polarization or instead exacerbates it. The remainder of this Article is devoted to that question. We begin by surveying the landscape of state litigation, mapping the many different ways that state AGs can shape national policy, and describing some of the institutional and doctrinal changes that have caused such litigation to flourish. We then examine how the various categories of state litigation relate to polarization at both the federal and state levels.

II. The Flowering of State Public-Law Litigation

In recent decades, state AGs have emerged as a uniquely powerful cadre of lawyers. As the chief legal officers for their respective states, AGs are responsible for enforcing state law and defending the state against legal challenges; in many areas, they also share responsibility with federal agencies for enforcing federal law.[97] Independently elected in forty-three states, AGs stand at the top of organizational hierarchies that operate alongside—and sometimes in opposition to—other institutions for state policymaking.[98]

Although state public litigation goes back considerably further, state AGs’ work first grabbed the national spotlight in the 1990s, when AGs from different states banded together to take on Big Tobacco. Although AGs were by no means the first lawyers to sue the tobacco companies, they succeeded where others had failed, securing a settlement that required substantial changes in tobacco marketing and payments to the states totaling more than $206 billion.[99] In more recent years, AGs have targeted, and ultimately disrupted, settled industry practices by paint producers, toy manufacturers, pharmaceutical companies, and auto companies—among others. As one corporate lobbyist put it, “In some ways, [AGs are] more powerful than governors . . . . They don’t need a legislature to approve what they do. Their legislature is a jury. That’s what makes them frightening[.]”[100]

State litigation is not just practically significant; it is also politically salient. And as AGs have become increasingly active and entrepreneurial, they have also attracted criticism from various quarters—including from other AGs.[101] Critics claim that state litigation is driven by partisan ambitions rather than a desire to vindicate the interests of the states qua states. We take up those critiques in Part III. Our goal here is to provide a positive account of what state public-law litigation is, and what makes it possible.

Before proceeding, a few words on terminology and scope: we use the term “state public-law litigation” because we want to address a particular subset of litigation by state AGs. We do not focus on government-contracts litigation involving the state, ordinary civil enforcement of state regulatory laws, or most individual criminal prosecutions. Rather, our subject is more like the category of impact litigation undertaken by public-interest lawyers. Just as public-rights cases brought by nongovernmental organizations seeking broad reforms became a critical category of litigation in the late twentieth century, requiring courts and scholars to rethink a litigation model predicated on the enforcement of private rights,[102] so too litigation by state governments has increasingly taken on a public-law cast.

That said, the category remains fuzzy. Although one can easily identify examples of state public-law litigation, such as the state lawsuits challenging the ACA or the Trump travel bans, delimiting principles are harder to come by.[103] Because our interest is in the practical impact of state litigation on American politics and the federal system, we want to define the relevant category fairly loosely. What we have in mind is (1) litigation activity (not only filing lawsuits but also defending them and participating as amici) (2) by states[104] that is (3) intended to have a legal and/or political impact that transcends the individual case and the jurisdiction where the action takes place.

A. The Engines of Expanding State Litigation

Prior to the 1980s, most state AG offices could be described as “[p]lacid and reactive.”[105] Things changed dramatically over the next few decades. The “New Federalism” of the Reagan Administration devolved countless regulatory and administrative responsibilities from the federal government to the states.[106] As the workload of state agencies increased, so too did their litigation exposure—with the burden of defense falling on state AGs.

Recognizing their AGs’ significant new responsibilities, states allocated more resources to them.[107] Higher budgets and greater responsibilities, in turn, drew a new breed of attorney to the AG’s office. Increasingly, the “state’s law firm” was staffed with “a younger, better educated, and more ambitious caliber of attorney.”[108]

As institutional capacity expanded, so too did the opportunities to use it. When federal agencies decreased their enforcement activities in the 1980s, state-level enforcers rushed in to fill the void.[109] Areas like antitrust and consumer protection, once dominated by the federal government, became enclaves of aggressive state enforcement.[110] Many AGs established specialized units and task forces to handle their new responsibilities, thereby “enhanc[ing] the role of the attorney general as a ‘public interest lawyer’ and offer[ing] many opportunities to improve the quality of life for citizens of the states and jurisdictions.”[111]

Meanwhile, new provisions of federal law facilitated state litigation by authorizing state AGs to enforce federal statutes, often by suing as parens patriae to protect the rights of state citizens.[112] The common law doctrine of parens patriae dates back to early English practice, in which the King exercised certain royal prerogatives as “parent of the country.”[113] In its more modern form, the doctrine allows states to vindicate sovereign or quasi-sovereign interests, including an “interest in the health and well-being . . . of [their] residents in general.”[114] Today, many state and federal statutes explicitly authorize states to sue as parens patriae.[115] Others can be read to authorize state suits implicitly by creating broad rights of action for citizens whom the states represent.[116] And even absent specific statutory authorization, state AGs may (depending on state law) have common law or constitutional authority to litigate as parens patriae on behalf of citizens.[117]

The 1990s tobacco litigation built on, and spurred, expansions in AG authority. Prior to the states’ assault on Big Tobacco, countless private plaintiffs had sued under a variety of tort and warranty theories—all seeking to hold the industry accountable for peddling an unreasonably dangerous product. None succeeded.[118] Many plaintiffs were simply outspent by the defendants; others were turned away on the ground that they had assumed the risk of smoking; and still others were thwarted by courts’ refusal to permit large numbers of smokers to sue together as class actions.[119]

Then came the states, which were able to avoid the pitfalls of earlier litigation and bring the tobacco companies to the bargaining table. Most states pursued restitution actions, seeking reimbursement for Medicaid expenses incurred in the treatment of smoking-related illnesses.[120] By shifting the focus from individual smokers to the states’ own losses, the state suits were able to cut off the tobacco companies’ prime defense strategy: blaming individual smokers. As Mississippi AG Mike Moore put it, “This time, the industry cannot claim that a smoker knew full well what risks he took each time he lit up. The state of Mississippi never smoked a cigarette. Yet it has paid the medical expenses of thousands of indigent smokers who did.”[121] Similarly, the states’ strategy allowed them to avoid the challenges of class certification: “[I]nstead of millions of plaintiffs, there would only be one. Concerns over common issues of fact, which doomed earlier class actions to fail the predominance and superiority tests of federal and state class action statutes, would be finessed.”[122] Ultimately, forty-six states joined the Master Settlement Agreement, which required the tobacco companies to pay the states more than $200 billion over twenty-five years and to agree to an array of regulatory constraints.[123]

Although the tobacco litigation is in some ways sui generis, it highlights several features that have helped fuel state litigation more broadly. First, the tobacco suits entailed an “unprecedented” degree of interstate cooperation among AGs, and their success made clear—to AGs as well as to potential defendants—the power of concerted multistate action.[124] Second, the litigation demonstrated the value of cooperation between AGs and private attorneys. The states’ suits benefited from substantial assistance and financing from private lawyers—a pattern that has been repeated in many subsequent actions. By teaming up with private counsel (particularly those willing to work for a contingent fee), state AGs can expand their reach into litigation that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive or resource-intensive, or would require specialized expertise.[125] Third, the staggering size of the settlement—“the largest transfer of wealth as a result of litigation in the history of the human race”[126]—revealed just how lucrative state litigation could be. In the years since the tobacco litigation, state AGs have become adept at using large monetary recoveries to publicize the financial contributions they make to the state and its citizens.[127] In many states, moreover, AG offices can retain certain types of financial recoveries, making litigation a self-sustaining endeavor.[128]

Finally, the states’ legal theories in the tobacco cases created a template for future actions against industries that cause widespread harm to state citizens.[129] The recoupment strategy alone is a powerful tool for recovering the states’ own expenses[130] and becomes more powerful still when combined with the states’ authority to sue as parens patriae to address harms to their citizens.[131] In the ongoing state efforts against opioid manufacturers, for example, the states have asserted various common law tort claims and are seeking recovery for harms to citizens and to their own proprietary interests, including “billions of dollars in damages to the State related to the excessive costs of healthcare, criminal justice, education, social services, lost productivity; and other economic losses as a direct result of the illicit use of these dangerous drugs caused by opioid diversion.”[132]

Courts—state and federal—have also played a role in the growth of state AG litigation. Perhaps most importantly, they have taken an expansive view of state standing. In Massachusetts v. EPA, the Supreme Court cited Massachusetts’s “stake in protecting its quasi-sovereign interests” as a reason for “special solicitude” in the standing analysis.[133] Long before those words were penned, lower federal courts had held that states can sue as parens patriae to vindicate their citizens’ rights under the federal constitution, even in circumstances in which the citizens themselves would lack standing. For instance, whereas the rule of City of Los Angeles v. Lyons makes it difficult for private parties to seek injunctive relief from sporadic instances of official misconduct,[134] courts have permitted states to sue in equivalent cases.[135] Similarly, as noted above, courts recognized states’ standing to sue the tobacco companies to recoup the expenses they had incurred as a result of smoking-related illnesses suffered by their citizens. When unions and other private organizations asserted similar claims, however, courts ruled that their injuries were too remote to establish standing.[136]

Representative suits by states also enjoy a host of other procedural advantages over their closest private analogues, class actions. Whereas class actions are governed by a complex set of procedural requirements designed to promote judicial economy and protect the interests of absent class members, courts have declined to apply those rules to similar suits by states—even as they have tightened up the requirements for private suits.[137] Courts have likewise refused to subject parens patriae suits to the jurisdictional requirements of the Class Action Fairness Act[138] or to mandatory arbitration clauses.[139] And when faced with simultaneous suits by states and by private class counsel, courts have often denied certification to the private class action on the ground that the state suit is the “superior” method of adjudication.[140] As one court put it, “[T]he State should be the preferred representative” of its citizens.[141]

It is not surprising, then, that state litigation activity has increased markedly in both volume and visibility in recent decades. For example, the number of Supreme Court cases in which states are parties has shot up since the 1980s—spurred in part by the creation in 1982 of the National Association of Attorneys General (NAAG) Supreme Court Project.[142] Even more notable is the increase in states’ filings as amici. Such filings are not command performances but represent AGs’ discretionary decisions to devote limited resources to Supreme Court advocacy.[143] The most comprehensive study of state litigation in the Supreme Court reports that since 1989 states have “become exceptionally active amicus curiae participants. They account for 20% of all certiorari petitions accompanied by an amicus brief and 18% of the amicus briefs on the merits.”[144] Today, states’ participation in the Supreme Court—both as direct parties and as amici—is second only to that of the federal government.[145]

The Supreme Court may be the most prominent venue for state litigation, but it is hardly the only one. States also have become more frequent litigants in the state and lower federal courts. Texas’s Greg Abbott sued the Obama Administration “at least 44 times”;[146] AG Maura Healy of Massachusetts reportedly “led or joined dozens of lawsuits and legal briefs” challenging the Trump Administration in 2017 alone.[147]

And states are now far more likely to band together in litigation in order to maximize their impact. For example, Paul Nolette found a marked increase in “coordinated AG litigation”—defined as filed lawsuits as well as preliminary investigations involving coordinated activity by at least two AGs—from 1980 to 2013. Professor Nolette reports: “From a consistently low number of one to four cases a year throughout the 1980s, the quantity of multistate cases . . . gradually increased, reaching twenty for the first time in 1996, thirty in 2002, and forty in 2008.”[148] The number of AGs participating in such cases also has grown, with a greater proportion of multistate cases involving sixteen or more states in recent years.[149] As Nolette explains, “Litigation involving over half of the nation’s AGs, once an unusual event, represents over 40% of all the multistate cases conducted since 2000.”[150] For many observers, AG activism amounts to “a major shift in how political fights are waged.”[151]

B. Mapping State Litigation

We know states are doing more litigation, but the aggregate numbers can only tell us so much. Although discussion of high-profile state litigation sometimes treats it as a unitary category, that perspective obscures important variation within the genre. This section maps state litigation into several discrete types, based on the nature of the claims asserted. We begin with the kinds of cases observers typically associate with state public-law litigation—cases in which states are pitted against the federal government. These include (1) claims that federal government action exceeds the limits of national regulatory authority, as in the state challenges to the ACA; (2) claims that federal government action violates aspects of the national separation of powers, as in state challenges to President Obama’s immigration policies; and (3) claims that federal government action violates individual federal rights, as in the state lawsuits against President Trump’s travel bans. It bears emphasis, however, that states can also shape policy outside their borders by targeting primary behavior directly, in suits against private actors alleging violations of either (4) state or (5) federal law.

To be sure, many prominent lawsuits will fall within more than one of these categories. For example, challenges to President Trump’s travel bans have sometimes included both claims that the bans violate individual rights and claims that the President has exceeded the scope of his lawful executive authority.[152] And state amicus briefs concerning the validity of the federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) raised both federalism and individual rights arguments.[153]

Each category also includes legal claims and arguments asserted by states in a variety of settings—including, for example, not only lawsuits but also amicus filings by state AGs. We define our categories by the legal claim asserted, not the form in which that claim is advanced. And, while we have framed our categories as challenges to the legality of either federal governmental or private action, we also include states’ assertion of arguments—often in opposition to other states—affirming the legality of those actions.[154]

1. Federal Power Claims.—This category contains claims that federal action exceeds the legal limits of national authority. The paradigmatic claims are those about the reach of Congress’s enumerated powers.[155] For example, minutes after President Obama signed the ACA, thirteen states filed suit arguing that Congress lacked power under the Commerce Clause to require individuals to buy health insurance.[156] Sometimes states raise these sorts of claims as a preemptive strike on federal legislation, as in the ACA case. Perhaps more often, these issues are raised by private parties as defenses to the imposition of federal requirements or penalties,[157] or in suits for a declaratory judgment or an injunction seeking to bar enforcement of federal law.[158] States then come in as amici—sometimes on both sides of the case.[159]

These cases are high visibility but, we want to suggest, of limited practical importance. They’re just not very promising, given the Court’s capacious understanding of national enumerated powers.[160] The Commerce Clause is very, very broad—and even where it’s not broad enough, there is the Necessary and Proper Clause to fill most gaps.[161] (In the healthcare case, the Taxing Clause saved the day for the ACA.)[162] We may see occasional wins for states here, but they’re likely—as in Lopez—to be mostly symbolic in their importance.[163]

The more significant cases are those in which Congress seeks to enlist state officials to implement federal law but arguably lacks power to do so. Most federal programs rely on state and local officials for enforcement and implementation. Polarization makes states governed by the party that is out of power in Washington particularly likely to want to opt out of such programs. Under the Anti-Commandeering Doctrine, Congress can’t require state officials to implement federal policy.[164] Instead, Congress typically conditions federal benefits (usually money) on state cooperation.[165] Challengers therefore argue that federal spending conditions are insufficiently clear or amount to federal coercion, as in the Medicaid Expansion portion of the healthcare case[166] or in the current challenges to the Trump order on sanctuary cities.[167] Alternatively, states’ claims may focus on whether certain federal requirements really amount to commandeering.[168]

This latter class of cases operates within a cooperative federalism context rather than a model of federalism where states have their own exclusive sphere of regulatory jurisdiction outside of federal authority.[169] But rather than seeking to control the content of federal policy, these cases generally try to preserve states’ ability to opt out. The Printz litigation that established the anti-commandeering principle for state executive officers did not try to strike down the federal Brady Act; it simply protected the right of state and local officials not to participate in its enforcement.[170] Likewise, the Medicaid expansion decision established an opt-out right for states.[171]

Finally, an important class of federal-power claims involves state immunities from federal regulation. These claims arise defensively, typically in response to claims by private litigants.[172] For a brief period during the late 1970s and early 1980s, state and local governments asserted immunities from federal regulation itself under the now-defunct National League of Cities doctrine.[173] More enduring principles shield state governments from certain judicial remedies when they violate federal requirements. A line of cases stretching back over a century—but intensifying under the Rehnquist Court—recognized a broad principle of state sovereign immunity shielding states from damages claims brought by individuals for violations of federal law.[174] More recent cases have constricted federal civil rights claims against state and local officers for violations of federal statutory requirements.[175] States have participated in these cases as both party defendants and extensively as amici (again, often on both sides).[176]

These immunity cases differ from most of our examples of state public-law litigation in that they arise defensively—they are not, as it were, examples of AGs like Texas’s Greg Abbott going into work and suing the federal government. Nonetheless, they do seem part of a systematic effort to expand protections for state and local governments under federal law. It seems fair to view Jeffrey Sutton’s successful advocacy of an expansive view of state sovereign immunity in cases like University of Alabama v. Garrett[177] and Kimel v. Florida Board of Regents,[178] for example, as an extension of his entrepreneurial tenure as State Solicitor of Ohio.[179]

2. Federal Separation of Powers Claims.—It’s less intuitive to think of States making separation of powers arguments, but one can find examples reaching way back: in 1970, for example, Massachusetts filed an unsuccessful original action in the Supreme Court challenging the constitutionality of the Vietnam War.[180] Separation of powers claims have become far more prevalent over the past decade or so. As we’ve noted, polarization tends to cause gridlock, even with a nominally unified government in Washington. And gridlock encourages the President to reach for his pen and phone to get things done.[181] Resulting challenges sound in separation of powers, not federalism. But the litigation is motivated by states that are either seeking to protect their own autonomy or to find a way to participate in a national lawmaking process that has shifted from Congress to the Executive Branch.

United States v. Texas—the immigration case—is a good example.[182] When President Obama extended lawful presence to millions of additional undocumented aliens, it was hard to argue that the deferred-action programs (Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA) and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)) fell outside the authority of the national government as a whole. Instead, state challengers contended that the President lacked the authority to—as Obama himself put it—“change the law” without going to Congress.[183] As was clear to all involved, Congress’s general intransigence on the immigration issue meant that a decision against executive authority would be—for all intents and purposes—a decision against federal authority more generally.

A separate set of process arguments are statutory but serve a constitutional purpose. Again, the immigration case is a good example. Texas’s successful argument in the district court was simply that Obama’s policy change had failed to comply with the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) because it had not gone through notice and comment. Notice and comment isn’t an insurmountable hurdle for agency lawmaking, but it does delay implementation of national policy. More importantly, it allows states—like anybody else—to insist on direct input into the federal lawmaking process. It allows states to be heard at the agency just as they are supposedly heard in Congress, although without any special status vis-à-vis other participants. Provisions in the APA for notice and comment, as well as for judicial review of process failures at the agency, effectively operate as separation of powers-type constraints on the administrative state.[184]

The separation of powers principle that Congress—not the President—makes the law also generates a second kind of challenge to federal action. That challenge argues that executive action—like the immigration order or the travel ban or the EPA’s clean power plan—is substantively inconsistent with the underlying statute.[185] Polarization can cause such claims to multiply. The longer gridlock persists, the more likely that new executive initiatives will stray from the obvious purview of the original legislation. So, for example, states challenged the Obama Administration’s transgender bathroom guidance on the ground that its definition of gender discrimination differs from that of the Congress that enacted Title IX of the Civil Rights Act.[186] Likewise, when federal agencies promulgated broad “preemption preambles” during the George W. Bush Administration, a coalition of states, as well as a state governmental association, filed amicus briefs arguing that these preambles exceeded the agencies’ statutory mandate.[187]

A more difficult class of cases involves litigation challenging federal government inaction. Federal administrative law generally presumes that agency inaction—at least in the form of agency refusals to initiate enforcement proceedings—are not subject to judicial review.[188] But this presumption can sometimes be overcome, as it was by Massachusetts v. EPA’s holding that states could challenge the agency’s denial of rulemaking petitions authorized by statute.[189] Given Congress’s continued failure to act on climate change, “EPA regulation pursuant to [Massachusetts v. EPA] . . . has served as the core of the US federal efforts on climate change.”[190] And where an incoming administration seeks to overturn previous executive action—thus arguably returning to the status quo ante of inaction—states may find greater leverage to challenge this departure from the prior baseline. Recent litigation over the Trump Administration’s “repeal” of President Obama’s DACA policy, for example, has gotten significant traction by arguing that the repeal rested on improper reasons.[191] State litigation to enforce the Executive’s statutory obligations can thus force adoption and continuation of executive policies even where national-level gridlock would otherwise foreclose them.

3. Federal Rights Cases.—Some state challenges to federal action rely not just on structural principles but also on individual rights arguments. In the travel ban cases, for instance, state governments assert parens patriae standing to raise the rights of their citizens. Sometimes states assert proprietary interests as well; some of the state plaintiffs in the travel ban cases argued that their state universities had been deprived of faculty and students from abroad.[192] And sometimes the states participate as amici to express a view on the scope of federal individual rights, as in the same-sex marriage cases.[193]

This category also includes state litigation activity contesting federal rights. For example, numerous states have participated as amici opposing Equal Protection challenges to affirmative action in state universities.[194] It is even more common to see states opposing rights claims by criminal defendants.[195] Similarly, states often play defense against federal civil rights claims brought by private litigants. (These two categories are often related, as many federal civil rights claims involve allegations of improper actions by state or local law enforcement.) In this latter set of cases, state governments are often the defendants; even where they are not (in the many cases against municipalities and their officers, for instance), they may well play a prominent role as amici.[196] And in all such cases, other states may support the party asserting federal rights as amici. When he was AG of Minnesota in the early 1960s, for example, Vice President Walter Mondale filed a brief on behalf of twenty-two states urging the Supreme Court to expand the right to counsel in Gideon v. Wainwright.[197]

As we discuss in more detail in the following Part, these rights cases create the potential for conflicts among states. Whenever state AGs support claims of constitutional rights, they are—in a very real sense—arguing against their own state’s power. More than that, they are seeking to impose a particular rule on all states. Like the statutory challenges described above, then, individual rights cases often involve interstate conflicts over control of federal policy. Those conflicts, moreover, can often be coded as red versus blue. And because they frequently involve “hot button” issues, these cases raise particular risks of politicizing the AG’s office.

4. State Enforcement of State Law that Creates National Regulation.—As we have already noted, the tobacco litigation of the 1990s was a critical watershed for state public-law litigation. To be sure, states have sought to enforce their own laws in ways that affect conditions outside their jurisdictions for a very long time.[198] And local governments have also been active in this sort of litigation—for example, in suits against the firearms industry during the 1990s.[199] But the most successful efforts have been undertaken by states. Most observers seem to agree that the tobacco litigation ushered in a new era of state activism that then spread to other regulatory areas and types of litigation.[200]

The tobacco litigation and its contemporary analogs share two related features that differentiate them from ordinary state enforcement of state law against private parties. The first is that rather than a single state suing a defendant within its jurisdiction for torts that harmed its citizens, the tobacco litigation featured a broad coalition of states—ultimately including all of them.[201] And the Master Settlement Agreement that ended the litigation eventually came to include nearly all manufacturers of tobacco in the American market. The litigation thus aimed at global peace—that is, a comprehensive settlement among all the relevant players.

The second point is that the tobacco settlement essentially created a nationwide regulatory regime governing cigarettes.[202] It includes, for example, not only payments by the defendants for past harms but also agreements to strengthen warning labels and restrictions on advertising. Because it applies throughout the United States and governs the activities of virtually all tobacco companies doing business here, one could fairly say that it might as well be a federal law.

Similar multistate litigation efforts have imposed quasi-regulatory regimes via comprehensive settlements with major industry players in the pharmaceutical and other industries.[203] We expect this phenomenon will continue. In the fall of 2017, for example, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts sued the credit-reporting company Equifax following announcement of a data breach that allegedly affected over 140 million consumers.[204] Massachusetts brought the suit under its own data privacy statute, as well as a more general consumer protection statute. If other states and credit reporting firms are drawn into this litigation, one might well see another comprehensive settlement with terms that would effectively act as, and possibly obviate, national regulation.

5. State Enforcement of Federal Law.—State AGs also can, and do, enforce many aspects of federal law. State enforcement of federal law is pervasive, from antitrust to consumer protection to environmental law.[205] As we explained above, this can happen either through explicit statutory authorization or through states relying on more general private rights of action, often asserting parens patriae standing to sue on behalf of their citizens.[206]

On its face, this category of cases may not seem particularly empowering for states, given that AGs are merely enforcing policies that already have been written into federal statutes and regulations. Yet the level of enforcement can have profound consequences for what the law means in practice, and for how regulated entities view their options. That is true even when the law’s substantive requirements are perfectly clear: higher levels of enforcement are likely to increase deterrence by raising the expected sanction for violations.[207] And when the relevant statutory or regulatory commands are somewhat less than pellucid—as is often the case—state AGs can shape policy on a national scale by pushing particular interpretations of vague or ambiguous federal laws.[208]

Thus, the most interesting instances for our purposes are those where state enforcement reflects a disagreement with national enforcement policy. The most salient recent example was Arizona’s effort to ramp up enforcement of federal immigration laws in response to what it saw as an abdication by federal authorities.[209] Another example, with a different political valence, would be Eliot Spitzer’s effort in New York to enforce federal environmental laws more aggressively than the federal EPA had previously been willing to do.[210]

Like the multistate cases described above, state enforcement of federal law can create the equivalent of regulatory policy nationwide. Given the interconnectedness of the national market, it’s hard to confine the effects of state enforcement within a particular state’s borders. If New York aggressively pursues Microsoft, Washington may feel aggrieved. And if pro-environment states undermine the fortunes of big oil companies, the oil-producing states may share in the consequences.

III. State Litigation, Politics, and Polarization

As state AGs have gained prominence, they have also attracted critics. A prominent theme in the critiques is that state litigation has moved away from its traditional core of defending “state interests” and into an uncertain new realm dominated by politics, partisanship, and policy debates.[211] Indeed, such critiques sparked the creation of a dissident AG organization, the Republican Attorneys General Association (RAGA), in 1999 as a way to “stop what they called ‘government lawsuit abuse’ and redirect state legal efforts away from national tort cases and back to traditional crime fighting.”[212] The creation of RAGA didn’t do much to stem state litigation, but it did help balance the political membership of AGs’ offices. AGs used to be overwhelmingly Democratic; there is now a much closer mix of Democrats and Republicans—due in part to aggressive campaign contributions and ads by the Chamber of Commerce and similar groups.[213] Many of those newly elected Republican AGs have themselves become active litigants, particularly during the Obama Administration.

The consequence is that it’s easy to paint state litigation as a partisan affair, with blue-state AGs challenging national policies or business practices that are defended by their red-state counterparts—or vice versa. Viewed from that perspective, the work of AGs seems destined to exacerbate, rather than ameliorate, the trends toward polarization that define our national politics.

We think the picture is considerably more complicated, as this Part explains. We begin by surveying what we know about partisanship and polarization among state AGs themselves, and then address the question that animates this Article: to the extent that state litigation is “political,” what should we make of that fact?

A. Polarization, State AGs, and State Litigation

When RAGA was founded in 1999, there were only twelve Republican AGs.[214] Today there are twenty-seven.[215] In the intervening years, AG elections have not only gotten more competitive,[216] they have also become more high-profile and more expensive. Drawing on data from the Database on Ideology, Money in Politics, and Elections (DIME), Figures 1 and 2 show the median and mean total campaign contributions reported by AG candidates in races from 1990 to 2012.[217] As the difference between the medians and means suggests, there are outliers in both directions—but particularly at the high end. Not all AG elections are expensive today, but some are very expensive. In 2012, for example, seven AG candidates reported fundraising totaling more than $1 million; Greg Abbott topped that list at $13.9 million.

Source: Adam Bonica, Database on Ideology, Money in Politics, and Elections: Public Version 2.0 (2016). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Libraries. https://data.stanford.edu/dime.

Note: In Figure 1, the top line is referencing “Median Dem” and the middle line is referencing “Median.”

Source: Adam Bonica, Database on Ideology, Money in Politics, and Elections: Public Version 2.0 (2016). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Libraries. https://data.stanford.edu/dime.

Note: In Figure 2, the top line is referencing “Mean Dem” and the middle line is referencing “Mean.”

These numbers must be taken with a grain of salt, particularly prior to 2000, when the data were spotty. But they are consistent with reports that more money is flowing into AG races, much of it from out of state.[218] And there is good reason to believe that the numbers have gone up (perhaps sharply) since 2012. RAGA, for example, raised $16 million in 2014—up from $470,000 in 2002.[219] Both RAGA and DAGA reported raising record sums during the first half of 2017 (up 45% and 73%, respectively, from the same point in the prior election cycle).[220] Both groups are also deploying their money more aggressively, after announcing in 2017 that they would end their longstanding “handshake agreement that they wouldn’t target seats held by incumbents of the other party.”[221] The effects were immediate: in one 2017 race alone, RAGA and DAGA collectively spent about $10 million.[222]

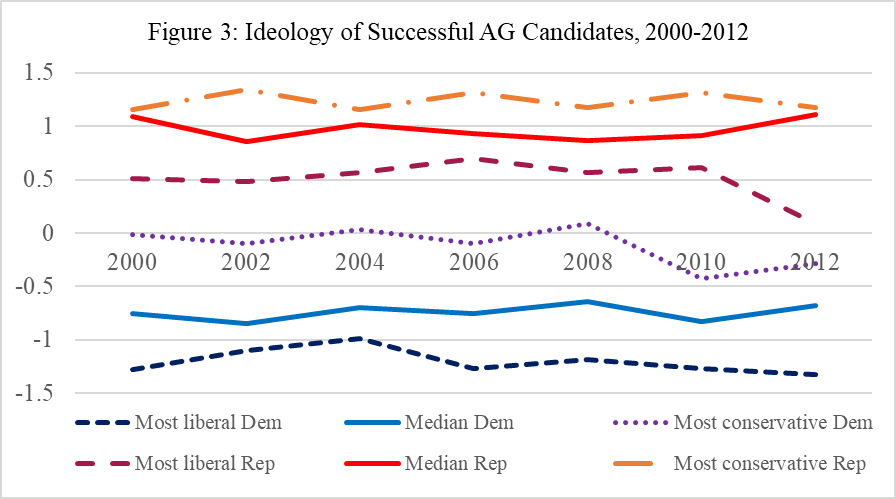

If AG races are more contentious than they once were, and if partisan associations like RAGA and DAGA are playing a more significant role in those elections, what are the consequences for AGs themselves? Do AGs reflect the same kind of partisan sorting and ideological divergence that characterize polarization at the federal level? Measuring polarization in AGs is no easy task, given the absence of conventional measurement tools—such as roll-call votes, which are the dominant tool for measuring ideology (and, thus, polarization) in Congress. But the available evidence suggests that the more general trends toward political polarization have not passed AGs by. To the best of our knowledge, the only current measure of AG ideology is from the DIME project, from which we drew the data on campaign contributions above. DIME is the brainchild of Stanford political scientist Adam Bonica, and it is more than a repository of information on campaign finance. Professor Bonica uses the contribution data to estimate the ideology of candidates based on the contributions they receive—“[t]he pattern of who gives to whom.”[223] Because many donors give to candidates at all levels of government, the ideology measures—known as CFscores—can compare the ideology of politicians in different types of offices (e.g., legislators vs. governors) as well as comparing different inhabitants of the same office (e.g., AGs from different states or AGs from the same state in different years).[224]