Sorry (Not Sorry): Decoding #MeToo Defenses

This Essay examines the text of over two hundred public statements issued by people accused of work-related sexual harassment and misconduct as part of the #MeToo movement. Using both computational and manual text analytics approaches, the project constructs a typology of the statements’ substantive content, including admissions, denials, defenses, and apologies; their emotional content, including anger, anxiety, and sadness; and their cognitive content, including authenticity and certainty. The project also tracks specific themes throughout the statements, including attacks on the accusers, references to changing workplace norms, addiction and mental health stories, and concerns about due process. Building on this descriptive picture, the Essay uses the statements to assess the #MeToo movement’s progress in holding individual perpetrators to account, and in achieving structural change.

None of them accuse me of doing anything other than, maybe, they didn’t like a joke I told.[1]

—Presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg, under questioning at a February 2020 debate about his alleged history of “crude, sexist comments” to women employees.[2]

I came of age in the 60’s and 70’s [sic], when all the rules about behavior and workplaces were different. That was the culture then.[3]

—Movie producer and convicted rapist Harvey Weinstein in a 2017 statement addressing multiple allegations of rape, sexual assault, and sexual harassment by female employees and other women.[4]

Introduction

In response to Bloomberg’s defense of humor gone wrong, audio of the debate records the audience booing and groaning loudly.[5] There was no live audience for Weinstein’s “times have changed” defense, but commentators at the time also issued a collective groan.[6] Actor Tom Hanks summarized these sentiments, saying, “You can’t buy, ‘Oh, well, I grew up in the ‘60s and ‘70s and so therefore . . . .’”[7] Yet both “times have changed” and “just joking” have become tropes in the accused’s responses to #MeToo claims.[8]

This Essay gathers over two hundred public statements like Bloomberg’s and Weinstein’s to study what the #MeToo accused say, and how they say it. Using a combination of computational text analytics and manual qualitative text analysis, the Essay constructs a typology of admissions, denials, defenses, and apologies. We also track specific themes, identifying, for example, instances of discrediting accusers, addiction and mental health stories, and concerns about due process. In addition, we examine the statements’ emotional content. Using algorithms that detect positive and negative emotions from text, and the intensity of expression, we classify statements by their emotional valence and then explore correlations between emotional and substantive content. Finally, we capture evidence of cognitive processes in the statements. We deploy tools to detect markers of authenticity/deception and certainty/tentativeness, and assess those attributes against both substance and emotion.

To preview the findings that follow, the statements were, on the whole, full of denials and defenses, including arguments about what “counts” as harassment, and references to the accused’s own career accomplishments. Apologies were relatively rare, appearing in only one-third of statements. Further, the defenses and denials were angry, certain, and intense.

Building on this descriptive picture, the Essay then moves to the normative. Here, we use the statements’ text to assess the #MeToo movement’s progress on two fronts: individual and structural. On the individual front, we ask whether the statements evince change, or a new understanding of the accuser’s perspective. Here, we omit all statements that contain a full denial—giving those accused the benefit of the doubt—and instead focus only on the statements that contain some admission or defense. These, we posit, are where the greatest possibility for individual change might lie, where the parties agree on what happened but might disagree as to its interpretation. Even with this limitation, relatively few statements contained language signaling that the individual accused was attempting to reconcile different perspectives, or to see their own behavior in a different light.

Even if all of the individual #MeToo accused adopted a new perspective on harassment and misconduct, however, this might only be weak tea. As writer Masha Gessen asks, “In the #MeToo revolution, does the focus on identifying bad actors distract us from breaking down the structures that enable them?”[9] Legal scholar Tristin Green raises a similar concern, observing, “Commentators and activists who are willing to work within the individualized frame . . . are likely to be sorely disappointed in the efficacy of their efforts.”[10] This is because the individual focus may result in reformed harassers, but does nothing to prevent the regeneration of harassment perpetuated by future harassers who emerge from the same institutional and cultural environment. As Vicki Schultz puts it, writing jointly with nine other legal scholars, #MeToo creates the chance “[t]o move beyond the status quo[,] . . . beyond individual solutions to approaches that hold institutions accountable for systemic harassment and its sources.”[11]

The Essay, then, mines the statements for evidence of structural change, of acknowledgment of power imbalances and commitment to change them. Here, too, the text offers up little hope. The statements are replete with references to the accused’s own power: their long careers, their many accomplishments. There are also repeated references to the harm to the accused and his/her family or company, and overall a relentless focus on the “I” rather than on the accuser and his/her perspective. Taken together, these textual characteristics reinforce the primacy and power of the accused, as against the inferior accuser. In this view, the statements themselves and the acts of misconduct that preceded them are both symptoms of the same underlying sexism and misogyny.

Thus, the Essay offers a somewhat dispiriting descriptive and normative analysis of #MeToo’s progress. However, these analyses perform a useful mapping function for #MeToo advocates, revealing the areas where the accused seem merely to be talking past their accusers and falling back on power-reinforcing tropes and themes.

The Essay proceeds as follows. Part I describes our data and methods and provides some initial descriptive statistics. Part II presents our analyses of the statements’ substance, while Part III discusses emotion and cognition. Part IV assesses the statements from the perspectives of #MeToo’s individual and structural goals. Supplemental materials appear in the Appendices.

I. Data, Methods, and Descriptive Statistics

The #MeToo movement began in October 2017 with a tweet by actress Alyssa Milano: “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet.”[12] As the movement gathered more tweets, and more public attention, The New York Times noted that “a great many powerful men [saw] their careers disintegrate, and with astonishing speed.”[13] By that newspaper’s math, allegations by 920 accusers “[b]rought [d]own 201 [p]owerful [m]en” over the course of 2017 and 2018.[14] The website Vox identified 262 notable people who were accused of misconduct during just seven months in 2017–2018,[15] Bloomberg News counted 429 over the full one-year period, presumably including those against the company’s owner,[16] and Time identified 414 in eighteen months.[17]

This Part describes our methods for identifying and gathering all available statements issued publicly by the #MeToo accused in response to the claims cataloged above. This Part also presents a basic descriptive picture of the industries of the accused and common language used in the statements.

A. Data and Methods

The text studied here comes from 219 public statements issued by people accused of sexual harassment or misconduct as part of the #MeToo movement, as of mid-2019. We assembled this set as follows. First, we gathered names of the accused from lists maintained by three online sources: the websites of the New York Times, Bloomberg, and Vox.[18] We cross-referenced the three lists to generate a set of 372 unique names. We then performed Google searches for any statement issued by the accused in response to the accusations. These statements included official statements labeled as such by the accused or their representative, and reported in the media; tweets; first-person posts on the accused’s own or other websites; and statements made during media interviews. This process produced a total of 273 statements issued between June 2017 and June 2019.

We then manually reviewed each statement to assess whether the underlying circumstance implicated sexual harassment law under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, i.e., where the accused was the present, past, or potential future employer of the accuser.[19] This scope is intentionally narrow: it retreats from the broader extralegal sweep of #MeToo in order to anchor the statements to the set of established employment-related sexual harassment definitions and defenses that have grown up under Title VII. Through this process, we discarded 54 statements, leaving our study set

of 219.

Notably, this process comes nowhere near to identifying the universe of all #MeToo allegations, as the lists that were our starting point comprised only people who were sufficiently notable to draw media attention when accused. Moreover, our search process likely failed to find some public statements. Nevertheless, this set of statements represents the most comprehensive compilation to date of public responses to workplace-related #MeToo accusations.[20]

To analyze these statements, we used both computational and manual methods. Here, we borrow a metaphor offered by computational political scientist Justin Grimmer. Grimmer analogizes collections of text to a haystack.[21] Humans are quite good at analyzing the characteristics and attributes of an individual straw (performing a close reading of text), but quite bad at efficiently and quickly sorting, organizing, or categorizing the entire stack of hay (grouping like statements with like statements).[22] Computers’ proficiencies are the reverse: they are excellent sorters but poor close readers.[23]

This Essay approaches the haystack of statements in both ways. We use computational methods to analyze the text as data, allowing us to find and exploit patterns in word usage to sort, organize, and classify the statements into useful analytical groupings. We also perform close readings, using our own human understanding of language and subject-matter expertise to extract meaning from the text that is relevant and useful in this particular domain. Throughout the remainder of the Essay, we identify and explain the particular methods we use in the various parts of our analysis. We turn next to some basic descriptive statistics that begin to reveal the shape and content of our statement set.

B. Descriptive Statistics

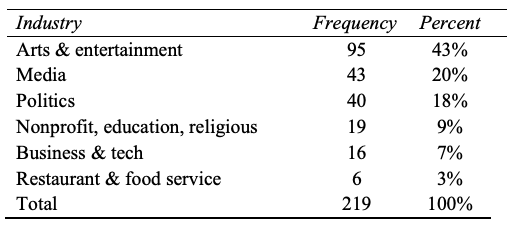

Among this set are 216 statements by men, or 99%. The remaining three accused were women. Table 1 below shows the distribution of statements by the industry of the accused. Perhaps unsurprisingly, due to the origins of the #MeToo hashtag in accusations by movie actresses, the arts and entertainment industry accounts for the largest proportion of the accused (43% of statements).

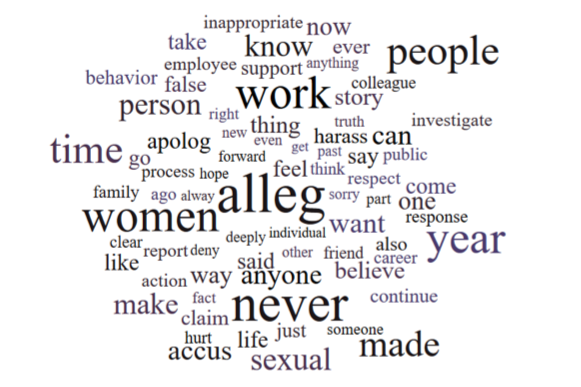

Figure 1: Top Seventy-Five Words by Frequency, Stemmed and Stopwords Removed

Nineteen percent of the statements appear to have been issued by third parties, including lawyers and agents speaking about the accused in the third person, and the remaining 81% use the first person. Those first-person statements are heavily subjective: in almost three-quarters of those statements, “I,” “me,” and other pronouns referring to the first person accounted for 10% or more of the words in a statement. We return to the topic of subjectivity—examining whose subjectivity is relevant in a sexual harassment analysis—later in the Essay.

Expanding beyond pronouns to all parts of speech, the average word count across statements is 1,148, though statement length varies considerably, from a minimum of one (“Lies.”), to a maximum of about 15,000 (an essay published on an accused’s website).

The word cloud in Figure 1 below illustrates the top seventy-five words by frequency across the whole statement set, where larger font size indicates heavier usage. The word cloud omits commonly used, low-value terms known as “stopwords” such as “the” and “and.” It also displays the words in stemmed format, meaning that “allegation,” “allegations,” and “allege,” for example, are combined in the word cloud as “alleg.”[24]

Table 1: Statements by Industry of Accused

The dominance of the “alleg” stem is also significant, along with “claim,” with both words appearing among the top seventy-five. As sexual harassment scholar Catharine MacKinnon points out, assumptions about truth and credibility are embedded in this terminology. She notes, “It is still generally said that women ‘allege’ or ‘claim’ they were sexually assaulted; those accused then ‘say’ or ‘assert’ it did not happen or ‘deny’ what was alleged.”[26] She proposes an alternative linguistic world, in which “[s]urvivors could ‘report’ sexual violation, or ‘say’ they were sexually violated. The accused could then ‘allege’ or ‘claim’ it did not occur, or did not occur as reported.”[27] The heavy use of “alleg” combined with “claim” in the text here suggests that we are far from MacKinnon’s proposed understanding.While word clouds do not provide sufficient information to support a detailed analysis, they nevertheless provide some access to the text’s main themes.[25] Here, the top two words are the adverb “never” and the stem “alleg.” The predominance of “never” aligns with the predominance of denials and defenses in the statements, discussed further in the following Part. Indeed, in some statements, over 20% of the words were negations, including not only “never,” but also “not,” “cannot,” “can’t,” and similar contractions.

The relatively smaller size of “sorry” and the stem “apolog” in the word cloud is also revealing, aligning with the scarcity of apologies in the statement set, discussed further below. Notably, if we sum the frequencies of “sorry” and “apology” on the one hand, and “false” and “deny” on the other, the two are almost equal: 118 versus 114. These totals draw only from the top seventy-five terms, but expanding the scope would likely reveal a further bias in favor of denial- and defense-related language over apology- and responsibility-related language. The manual review process described below delves further into this subject.

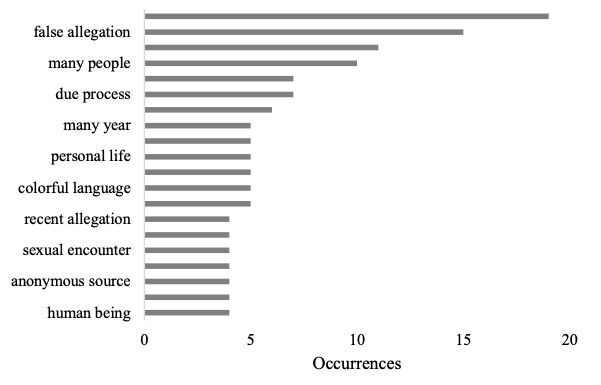

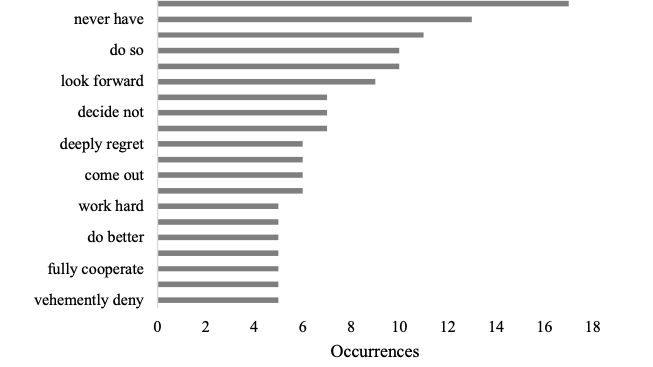

Moving beyond the word cloud, for a more granular look at the statements’ language, we used natural language processing tools to annotate each word by its part of speech.[28] This enriches the raw text by adding more information to our data about the types of words that are present and the linkages among them. For further detail, the figures in Appendix A list the top twenty nouns, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs by frequency across the statement set. With parts of speech identified, we are then able to examine multi-word phrases. Figure 2 below uses an algorithm called RAKE, or Rapid Automatic Keyword Extraction, to automatically identify the top twenty commonly co-occurring adjective–noun sequences across all statements.[29] Figure 10 in Appendix A presents RAKE-generated adverb–verb phrases

as well.

Figure 2: Top Twenty Adjective–Noun Phrases

Some of the top adjective–noun phrases in Figure 2 are notable because they square with the denial- and defense-heavy picture of the statements that has developed thus far, in particular “false allegation” and “false accusation.” Other phrases introduce themes that will develop further below: the “just joking” defense that minimizes the subjective and objective severity of the conduct (“colorful language”), referring to consent and/or welcomeness (“mutual flirtation”), and discrediting the accuser (“anonymous source”). The phrase “many year[s]” is also relevant to a common theme throughout the statements: the accused’s attempts at bolstering their own credibility by referring to their “many years” of professional or personal accomplishments. As explored further below, this type of language connects with an observation by Catharine MacKinnon about the centrality of the accused in sexual harassment narratives: “His career, his reputation, his mental and emotional serenity, his family—all his assets counted. Hers did not.”[30]

The next Parts turn from these preliminary descriptive statistics to our deeper examination of the statements’ substantive, emotional, and cognitive content. We use both manual review and computational tools—close investigations of single straws and automated sorting of the larger haystack. With these analyses, we then build toward a normative assessment of #MeToo’s progress in holding individual perpetrators to account, and in achieving structural change.

II. Substance

We begin with a typology of the statements’ substantive content. The results presented in this Part were produced via an iterative, inductive qualitative text analytic process, influenced by methods employed in psychology research.[31] Qualitative text analysis is appropriate where, as here, the researchers did not influence the process that generated the text, and did not interact with the speakers.[32] The approach draws on the related methodologies of phenomenological and discursive analysis, which focus, respectively, on understanding the speaker’s experience and the speaker’s communication of that experience.[33] Here, we are interested not only in the accused’s view of what happened, but also “what the [accused] were trying to accomplish through communicating their stories.”[34]

In constructing our substantive typology, we employed an inductive process where “themes and codes were not determined a priori, but rather were derived from the text itself.”[35] We first read the entire set of statements with an eye toward developing a set of consistently applicable, replicable codes that would capture the statements’ content.[36] We then made multiple coding passes through the statement set to refine the coding protocol and ensure consistent application across speakers and coders.[37]

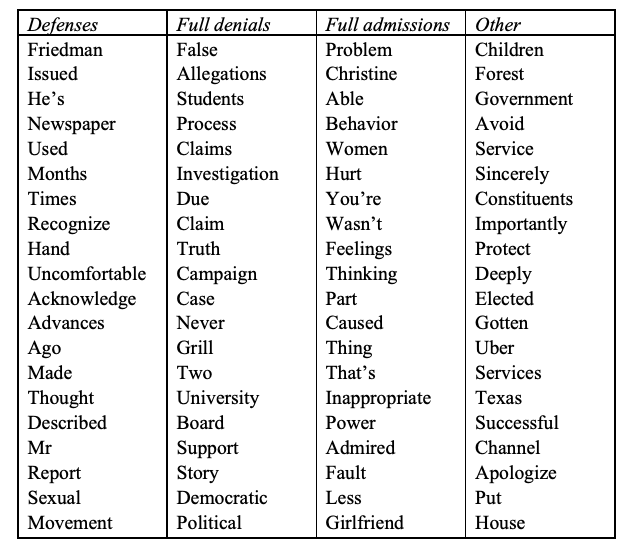

This process allowed us to classify the accused’s main response: defense, full denial, full admission, or other. As a robustness check, we used a computational “keyness” measure to identify the top twenty terms that best distinguished each category of response from the others.[38] The table in Appendix B lists the most “key” words, and reveals substantial differences in word usage across response categories.[39] This offers confirmation that our manual process identified distinct classifications of response. In addition to the accused’s main response, our manual process also extracted the types of defenses raised per statement, both legally cognizable and extralegal; the presence of apologies, both full and conditional; and a handful of other commonly occurring topics. Finally, we developed a rough measure of the accused’s legal risk and examined main responses, defenses, and apologies in that light.

A. The Accused’s Main Response: Full Admission, Full Denial, Defense, Other

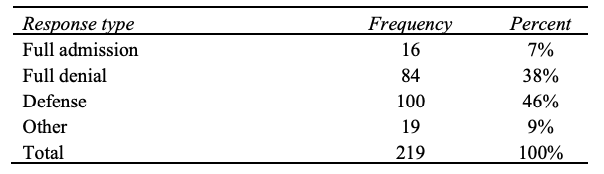

When faced with an accusation of sexual misconduct, the accused has a menu of response options. Here, we classify each statement into four mutually exclusive categories: full admission, full denial, defense, and other. Apologies, addressed separately below, might also accompany any of these responses. Table 2 reports the distribution of these responses across the 219 statements, where each statement is assigned a single classification.

Table 2: Main Response (One Classification per Statement)

Full denials (38% of statements), on the other hand, can take two forms. The accused might deny that he or she committed any act at all, full stop. An example, issued by tabloid gossip editor Dylan Howard, is, “Let me be crystal clear and very direct: The statement . . . attributed to me never came out my mouth. . . . There is nothing here that has any truth to it.”[42] Full denials also include statements that are unclear as to what the speaker is denying: the facts, their interpretation by the accuser, or both. An example comes from a statement by fashion photographer Bruce Weber: “I’m completely shocked and saddened by the outrageous claims being made against me, which I absolutely deny.”[43] It is unclear from Mr. Weber’s statement whether he is denying the facts, or denying that they rose to the level of harassment or misconduct. Nevertheless, his statement is clearly a denial of the allegations against him.As we conceive of it, a full admission (7% of statements) requires admitting that the accused committed the act(s) in question, and that the act(s) were wrong, constituted sexual harassment or misconduct, or otherwise violated some rule of conduct or behavior. In other words, a full admission engages with both the factual question of whether an event actually took place, and the question of how to interpret it.[40] An example of a full admission, by circus performer Barry Lubin, is, “The allegations are true. What I did was wrong, and I take responsibility for my actions.”[41]

A statement with a defense (46% of statements, a plurality) tends not to deny the facts, but instead argues about definitions and interpretation, or raises another type of defense that could justify or excuse the conduct. Here, we consider both legally cognizable defenses and other types of justifications and explanations that the speakers raise. All types of defenses are discussed further in the section that follows. Examples include Bloomberg’s “just joking” from the outset of this Essay, as well as Weinstein’s “times have changed.” Another comes from actor and producer Michael Douglas, arguing over the subjective and objective severity of the conduct in a variation on the “just joking” trope: “Coarse language or overheard private conversations with my friends that may have troubled her are a far cry from harassment.”[44]

Finally, in the “other” category (9% of statements), the accused does not admit, deny, or raise a defense, but instead only apologizes, or discusses other topics such as harm suffered by his or her family. An example, by union organizer Caleb Jennings, is, “I support the ongoing investigations, and I’m against any workplace sexual misconduct and abuse.”[45]

As Table 2 above shows, defenses and denials together account for 84% of statements. Even if we were to assume the truth of the full denials and omit those statements from the analysis, of the 135 statements that remain, almost three-quarters contain a defense. As later sections discuss, this distribution

is relevant to #MeToo’s individual frame: as a whole, the statements do not read as a set of individual reckonings, but rather the site of substantial disagreement about basic definitions and boundaries.

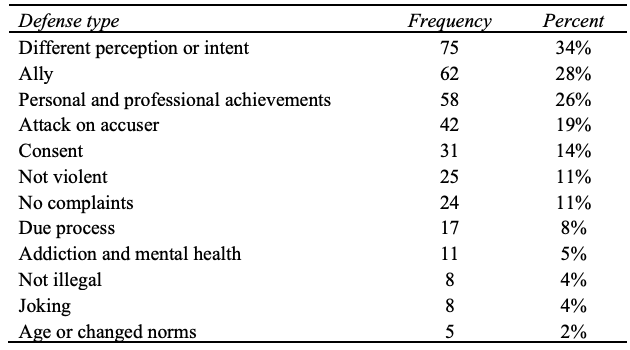

B. Defense Types

We now turn to the defenses that the statements deploy, which together make up the largest response type. Our qualitative text analysis identified twelve categories of defense, some of which would be cognizable as

defenses in a sexual harassment lawsuit under Title VII, and some of which are not formal defenses, but might nevertheless be raised in a defendant’s support.[46] Table 3 below reports their frequency, where multiple defenses

can be present per statement. The sections that follow group the twelve defenses into six categories: subjective–objective, consent/welcomeness, accused credibility, accuser credibility, due process, and other mitigating circumstances. The first two categories implicate Title VII; the remainder do not.[47]

Table 3: Defenses (Multiple Possible per Statement)

The common thread among these separate defenses is an argument that the allegedly harassing conduct was not serious enough to warrant censure, or was so excusable and understandable as to avoid sanction. Recall both Bloomberg and Weinstein, claiming, in so many words, “Surely you can’t blame me for a harmless little joke, or actions that were just out of step with the times.”

1. Subjective–Objective

The subjective–objective category is the largest of the six, comprising arguments about differences of perception or intent; claims that the accused’s actions were not violent, not illegal, and did not result in any previous complaints;[48] and the familiar “just joking” and “times have changed” defenses. One or more of these defenses were present in two-thirds of all statements.

In fact, questions of subjectivity and objectivity are central to sexual harassment law. Though Title VII was passed in 1964, harassment was not considered to be a covered form of discrimination until a 1986 U.S. Supreme Court case, Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson.[49] In Meritor, the Supreme Court recognized as actionable harassment conduct that is “sufficiently severe or pervasive ‘to alter the conditions of [the victim’s] employment and create an abusive working environment.’”[50]

The Court elaborated on the standard by which to judge severity and pervasiveness in Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc.,[51] decided in 1993. There, the Court found:

Conduct that is not severe or pervasive enough to create an objectively hostile or abusive work environment—an environment that a reasonable person would find hostile or abusive—is beyond Title VII’s purview. Likewise, if the victim does not subjectively perceive the environment to be abusive, the conduct has not actually altered the conditions of the victim’s employment, and there is no Title VII violation.[52]

The Harris Court listed a number of factors relevant to this inquiry, including “the frequency of the discriminatory conduct; its severity; whether it is physically threatening or humiliating, or a mere offensive utterance; and whether it unreasonably interferes with an employee’s work performance.”[53]

In the statements, arguments about objectivity and subjectivity are not explicitly labeled as such, but these definitional disputes are not far from the surface. The accused claim, variously, that their conduct was acceptable because it involved no violence or aggression,[54] or explain it away as a joke,[55] or excuse their actions as a product of their age or outdated social norms.[56] Each of these rhetorical moves makes an implicit argument that the conduct was not objectively severe or pervasive, or that no person—including the accuser—should subjectively perceive it as such.

A statement issued by former Ninth Circuit Judge Alex Kozinski provides an example of this tactic. Kozinski was accused by at least fifteen former employees of “inappropriate conduct and sexualized comments,” with one former clerk describing his chambers as “a hostile, demeaning and persistently sexualized environment.”[57] In response, he stated in part,

I’ve always had a broad sense of humor and a candid way of speaking to both male and female law clerks alike. In doing so, I may not have been mindful enough of the special challenges and pressures that women face in the workplace. It grieves me to learn that I caused any of my clerks to feel uncomfortable; this was never my intent.[58]

Kozinski makes several moves here, all of which seem designed to minimize the subjectively and objectively harmful impact of his actions and paint his accusers as especially sensitive. He refers to his sense of humor; his misunderstanding about workplace norms; and women’s “special challenges and pressures,” causing them to react negatively to his “jokes” while their male colleagues did not.

In addition, statements in this category often refer to the accused’s own benign intent or perception of the situation.[59] However, this is the wrong subjective point of view: the accused’s intent does not govern the subjectivity portion of the Title VII harassment analysis; it is the victim’s and survivor’s perception on the receiving end that matters.[60]

2. Consent/Welcomeness

The other legally cognizable defense under Title VII—consent/welcomeness—was present in 14% of statements. This defense makes reference to a group of related concepts: consent, voluntariness, welcomeness, mutuality, invitation, and encouragement. Consent defenses are positively correlated with third-party speakers, meaning that statements that make a consent/welcomeness argument tend to be issued by the accused’s lawyer, agent, or other representative. Consent, too, is faintly positively correlated with the presence of an addiction or mental health story—discussed further below—in the accused’s statement. This could suggest that the accused’s inability to assess consent, or welcomeness, was due to his or her own compromised judgment and perception—or at least that the accused is presenting his or her story in this way.

Three examples of this defense are as follows, by broadcast journalist Charlie Rose, college professor Avital Ronnell, and actor Richard Dreyfuss, respectively:

“I always felt that I was pursuing shared feelings, even though I now realize I was mistaken.”[61]

“[My] communications were repeatedly invited, responded to and encouraged by him over a period of three years.”[62]

“During those years I was swept up in a world of celebrity and drugs—which are not excuses, just truths. . . . I did flirt with her, and I remember trying to kiss Jessica as part of what I thought was a consensual seduction ritual that went on and on for many years. I am horrified and bewildered to discover that it wasn’t consensual. I didn’t get it. . . . It makes me reassess every relationship I have ever thought was playful and mutual.”[63]

Here, the specific definitions and concepts used within sexual harassment law are important.

As the Meritor Court explained, prior to any severity or pervasiveness inquiry, “[t]he gravamen of any sexual harassment claim is that the alleged sexual advances were ‘unwelcome.’”[64] According to the Court, the relevant question is not whether the accuser voluntarily engaged with the accused “in the sense of consent” but rather “whether [he or she] by [his or] her conduct indicated that the alleged sexual advances were unwelcome.”[65] Lower courts soon filled out this definition, identifying unwelcome conduct as that which the victim or survivor did not “solicit or invite” and which he or she personally found to be unwelcome.[66]

Thus, in sexual harassment law, the concepts of consent and voluntariness, on the one hand, are distinct from the concepts of welcomeness, mutuality, invitation, and encouragement, on the other.[67] Some of the statements tend to blur these lines, referring only to consent as a defense. It may be that the speakers’ use of this language was intended as a catchall to include welcomeness and related concepts and that it asks too much of the statements to expect perfect fidelity to sexual harassment law. However, the use of consent versus welcomeness language also may indicate something important about culture and structure—some of the bigger game that #MeToo is hunting. As explored further below, understanding welcomeness requires a measure of empathy from the accused, forcing them to move out of their own subjective perspective and attempt to occupy the accuser’s point of view. This is a different understanding from the one presented in many of the statements, which are fully and exclusively engaged with the accused’s own thoughts, perceptions, feelings, and beliefs.

Other statements do engage directly with concepts of welcomeness and mutuality, but claim to have misperceived the circumstances, as in Charlie Rose’s and Richard Dreyfuss’s statements quoted above. Comedian Louis C.K. provides another example. In a newspaper article, comedian, actress, and producer Rebecca Corry recounts that, when they both appeared on a television show, he approached her while she was walking to the set and asked to go to her dressing room and masturbate in front of her.[68] He later acknowledged that he had done this, saying, “I used to misread people back then.”[69] This, like similar statements, neatly echoes Catharine MacKinnon’s description of a typical defense to reports of sexual harassment: “She wanted it.”[70] As before, we return to these themes below.

3. Accused Credibility

In addition to the two legally cognizable defenses discussed above, the first extralegal defense that appears in the statements is attempts to bolster the accused’s credibility by reference to personal or professional accomplishments or using “ally” language that aligns the speaker with women, the women’s movement, feminism, or #MeToo generally. More than half of the statements—55%—contain this defense type.

Harvey Weinstein’s statement is relevant here too. After referring to changed workplace norms, he purported to quote a Jay-Z lyric,[71] pledged to take down the National Rifle Association, and described establishing a $5 million foundation in his mother’s name to fund scholarships for women directors at the University of Southern California.[72] This is a combination of ally language (the women’s scholarship) and bolstering (name-checking another prominent figure in the entertainment industry and displaying political clout). Vincent Cirrincione, a talent manager, similarly portrayed himself as an ally, while also referring to his career accomplishments:

We live in a time where men are being confronted with a very real opportunity to take responsibility for their actions. I support this movement wholeheartedly. I have had female clients and employees my entire career in this industry. I have built a reputation for advancing the careers of women of color.[73]

This bolstering brings to mind, yet again, Catharine MacKinnon’s observations about typical responses to sexual harassment claims. She writes:

[N]othing he did to her mattered so much as what would be done to him if his actions were taken seriously. His value, personal and political, outweighed hers. His career, his reputation, his mental and emotional serenity, his family—all his assets counted. Hers did not. . . . His value outweighed her violation.[74]

The 55% of statements identified in this section do not stray far from MacKinnon’s script, emphasizing the accused’s accomplishments and commitments, and therefore their credibility and value, over the accuser’s. We return to this theme below in our assessment of #MeToo’s progress as a movement for structural change.

4. Accuser Credibility

The flip side of bolstering the accused’s credibility is tearing down the accuser’s. Nineteen percent of the statements contained a specific attack on the accuser’s reputation by reference to a history of monetary demands and/or malicious targeting of the accused.[75] Television host Bill O’Reilly, for example, labeled his accusers “politically and financially motivated.”[76] Professor Alec Klein characterized his accuser as “a disgruntled former employee who had been on a corrective-action plan for poor work performance several years ago.”[77] Texas Senator Borris Miles’s statement refers to “powerful enemies.”[78]

While not a distinct, legal cognizable defense in a Title VII lawsuit, a defendant might attack a user’s credibility in order to undermine her testimony in the eyes of the factfinder. Accuser credibility is also relevant to the welcomeness analysis under Title VII, discussed further in the following section, where courts determine whether an alleged harasser’s conduct was invited by the victim or survivor.[79]

These sorts of credibility attacks are familiar in discussions of sexual misconduct, where, as MacKinnon explains, “She isn’t credible” has long been a common refrain.[80] Feminist philosopher Kate Manne observes similarly that such “testimonial injustice” occurs when “subordinate group members [are] . . . denied the epistemic status of knowers, in a way that is explained by their subordinate group membership.”[81] MacKinnon holds out hope, however, that the #MeToo movement is bringing about a credibility revolution, “eroding the . . . barriers” of “disbelief and trivializing dehumanization of [sexual harassment] victims.”[82] From the perspective of the statements studied here, however, credibility attacks remain a relatively common theme.

5. Due Process

The fifth set of defenses raised by the accused (8% of statements) are claims about fairness and due process. Examples include statements by two different California state legislators accused of sexual harassment: Tony Mendoza, who requested, “Fairness and due process is all that I ask,”[83] and Raul Bocanegra, who stated, “[T]he principle of ‘innocent until proven guilty’ has been temporarily lost in a hurricane of political opportunism among the self-righteous in my case—to the detriment of both the accuser and the accused.”[84]

Interestingly, due process defenses are positively correlated with references to God and religion, an additional topic discussed below. The two involve similar rhetorical moves: the speaker refers to some concept (fairness or faith) that is bigger than the particular accused and accuser, perhaps in an attempt to shift the focus away from the micro-level details of the accusations at hand.

Legal scholar Jessica Clarke has written about these sorts of arguments, pointing out that, as a technical matter, the Constitution’s due process protections do not apply to the vast majority of people who experience employment consequences as a result of #MeToo allegations.[85] This is because employees of private companies have no employment protections under the Constitution, and may be fired by their employers at will.[86] Nor do concepts of guilt and presumption of innocence, imported from criminal law, apply under Title VII.[87]

Clarke connects these types of due process arguments with the power structures that enable sexual harassment and misconduct in the first place. She notes that claims by the accused to “exceptional procedural protections,” i.e., due process when process is not due, may be “rooted in a sexist view of gender roles that presupposes that accused men have special entitlements to their careers, professional reputations, and future prospects because they are men, while women whose careers are derailed by harassment have not lost anything of value because they are women.”[88] This, of course, echoes Catharine MacKinnon’s observation about the relative relevance in #MeToo narratives of the accused’s careers and professional accomplishments—what they have to lose—compared with what the accusers have already lost.[89] This is the same message embedded in the accused’s bolstering language, discussed above, as well as in references to family, friends, and colleagues, discussed below.

6. Other Mitigating Circumstances

The final category of defense, present in about 5% of statements, cites other mitigating circumstances offered to excuse or explain the accused’s conduct. Primary here are addiction and mental health narratives. Writer and documentarian Morgan Spurlock, for example, cites both in his statement:

I have helped create a world of disrespect through my own actions. And I am part of the problem. But why? What caused me to act this way? Is it all ego? Or was it the sexual abuse I suffered as a boy and as a young man in my teens? Abuse that I only ever told to my first wife, for fear of being seen as weak or less than a man? Is it because my father left my mother when I was [a] child? Or that she believed he never respected her, so that disrespect carried over into their son? Or is it because I’ve consistently been drinking since the age of 13? I haven’t been sober for more than a week in 30 years, something our society doesn’t shun or condemn but which only served to fill the emotional hole inside me and the daily depression I coped with.[90]

As with the bolstering references to the accused’s accomplishments, these narratives are primarily self-centered, and would therefore be vulnerable to MacKinnon’s accusation that they are asserting the primacy of “[h]is value” over “her violation.”[91] Yet perhaps these statements should be read more charitably, as attempts at empathy, exposing the accused’s own pain as a way to identify with the accused. This theme of empathy is central to the normative discussion below.

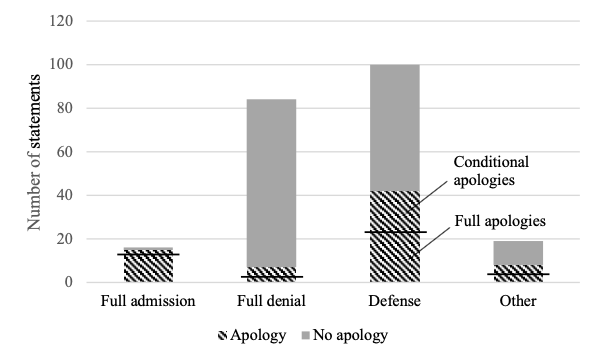

C. Full and Conditional Apologies

This section now turns from defense language to apologies. Here, we distinguish between two types of apology, which we label full and conditional. As legal, psychology, and philosophy scholars Lesley Wexler, Jennifer Robbennolt, and Colleen Murphy explain in their work on #MeToo and restorative and transitional justice, “apologies that are conditional . . . or refer only generally to ‘actions’ or ‘behavior’ do not acknowledge the harmful behavior or demonstrate an understanding of its wrongfulness or its effects.”[92] Further, a conditional apology “appears to place fault on the victim for misinterpreting or being overly sensitive.”[93] In contrast, full apologies take complete responsibility for the speaker’s conduct, and its impact, without condition.

Figure 3 below shows all apologies per each response type, with the proportion of all apologies indicated by the darker bar overlay and the proportions of full and conditional apologies indicated by the line segmenting each bar.

Figure 3: Apologies per Response Type

In total, only one-third of the statements included an apology of any kind. Fifty-six percent of those apologies were full apologies; 44% were conditional. Full apologies occurred most frequently as a proportion of full admissions, as shown in Figure 3 above. Conditional apologies co-occurred most frequently as a proportion of the “other” category of response, likely because those responses often only contained apologies rather than an admission, denial, or defense. These correlations make sense: speakers who are taking full responsibility for their actions are the most likely to admit fully to those actions and to their interpretation by the accuser.[94]

Among the full apologies were statements made by chef Charlie Hallowell:

I can see very clearly that I have participated in and allowed an uncomfortable workplace for women. For this I am deeply ashamed and so very sorry. We have come to a reckoning point in the history of male bosses behaving badly, and I believe in this reckoning and I stand behind it. I understand that I cannot right the past wrongs, and at the same time, I take full responsibility for all of my actions.[95]

Other full apologies came from statements by entrepreneur Dave McClure and showrunner Chris Savino, who stated, respectively:

“My behavior was inexcusable and wrong. . . . I’d like to sincerely apologize for making inappropriate advances towards her several years ago over drinks, late one night in a small group, where she mentioned she was interested in a job . . . .”[96]

“I am deeply sorry and I am ashamed.”[97]

In contrast, examples of conditional apologies appeared in statements by radio and television personality Ryan Seacrest (“If I made her feel anything but respected, I am truly sorry.”)[98] and Alaska state legislator Dean Westlake (“I sincerely apologize if an encounter with me has made anyone uncomfortable.”).[99]

As discussed further below, the fact that full apologies outnumber conditional ones can be read as promising for both #MeToo’s individual and structural goals. However, conditional apologies—with their implicit responsibility-shirking and victim-blaming—still represent nearly half (44%) of all apologies in the statement set, somewhat tarnishing this silver lining.

In addition to apologies, our study also identified statements in which the accused express a new understanding of their own conduct and its impact or other evidence of self-growth. Fifteen percent of statements included such expressions of growth. For example, television producer Dan Harmon accompanied his apology with the following:

The last and most important thing I can say is just think about it. No matter who you are at work, no matter where you work, in what field you’re in, no matter what position you have over, under, or side by side with somebody, just think about it. Because if you don’t think about it, you’re going to get away with not thinking about it and you can cause a lot of damage that is technically legal and hurts everybody. And I think we’re living in a good time right now because we’re not gonna to [sic] get away with it anymore. If we can make it part of our culture that we think about it and possibly talk about it, then maybe we can get to a better place where that stuff doesn’t happen.[100]

Comedian Louis C.K., too, expressed introspection and revelation in his official statement, released after the newspaper article that included Rebecca Corry’s account, quoted above. The relevant passage reads:

These stories are true. At the time, I said to myself that what I did was O.K. because I never showed a woman my dick without asking first, which is also true. But what I learned later in life, too late, is that when you have power over another person, asking them to look at your dick isn’t a question. It’s a predicament for them. The power I had over these women is that they admired me. And I wielded that power irresponsibly. I have been remorseful of my actions. And I’ve tried to learn from them. And run from them. Now I’m aware of the extent of the impact of my actions.[101]

Of course, we have no way to assess whether these expressions of self-growth are genuine. In addition, learning not to propose taking out one’s penis at work is not the most profound example of personal progress. Nevertheless, if we read these statements charitably, then they contain a glimmer of hope for #MeToo’s progress, at least on the individual level.

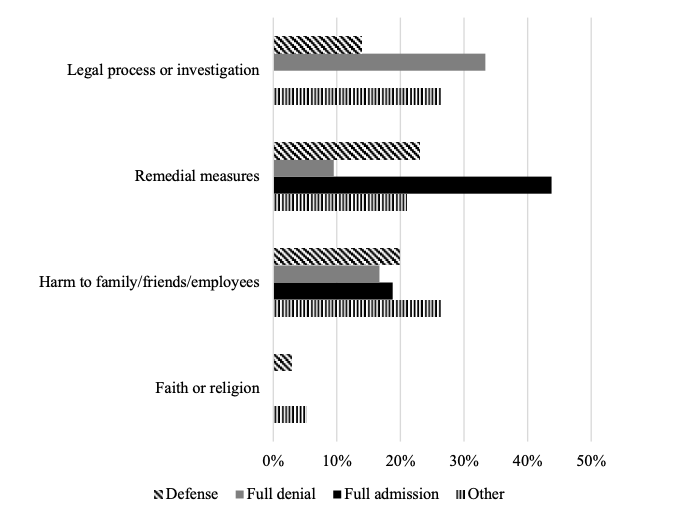

D. Other Common Topics

Finally, a set of substantive topics emerged from our inductive review of the statements’ content. These do not fit neatly into any of the categories discussed above. They are references to an ongoing legal process or investigation (21% of statements); descriptions of remedial measures that the accused or the accused’s company have taken (19%); harm to the accused’s family, friends, or employees caused by the #MeToo allegation (19%); and references to God, faith, or religion (2%). Figure 4 shows their distribution across response types.

Figure 4: Other Common Topics per Responses Type

As Figure 4 shows, references to legal processes are most common in the full denial category. This stands to reason: an accused might be especially careful to issue a public denial of #MeToo claims if there is an ongoing lawsuit or criminal prosecution against him or her. References to remedial measures, in turn, appear most frequently in full admissions. This, too, makes sense, as the accused who “come clean” in their statements might also make forward-looking pronouncements about the changes that they themselves and their companies are making to avoid future sexual harassment and misconduct. This topic is quite relevant to the discussion, below, of structural change.

Finally, the last two topics—harm to family/friends/employees and references to faith and religion—appear most frequently alongside defenses and in the “other” response category. In MacKinnon’s view, these references merely serve to reinforce notions of hierarchy and power. Why, one can imagine her asking, would an accused’s belief in God or love for their family be relevant in a sexual harassment inquiry? The presence of these topics, she would suggest, functions to assert the accused’s worth and, implicitly, values it above the accuser’s.

E. Legal Risk

This Essay does not engage with the question of why any particular statement contains an admission, denial, defense, apology, or other topic, largely because we lack full information about the circumstances that gave rise to each #MeToo allegation and the accused’s statement in response. However, an accused’s own legal exposure, and/or the vicarious liability of his or her company, is most likely a powerful driver of the accused’s strategy in responding.[102] To explore this possibility, we constructed a rough proxy for legal risk: whether a statement mentioned ongoing legal proceedings of any kind, and whether it was written in the third person, referring to the accused as “he” or “she.” If a statement fell into either of these categories, we gave it a “legal risk” flag. We then explored correlations between legal risk and main responses, defenses, and apologies.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, 81% of statements with an indicator of legal risk contained either a full denial or defense as the main response. The defenses that appeared most frequently among the legal risk statements were those that would be cognizable in a Title VII lawsuit (subjective–objective and consent/welcomeness). Finally, and again unsurprisingly, apologies were almost four times more likely to appear in statements with no suggestion of legal exposure than in legal risk statements.[103]

These preliminary observations raise many interesting philosophical and practical questions that are beyond the scope of this Essay: whether apology is a social good and the threat of litigation improperly discourages beneficial expressions of remorse; whether the public articulation of a legal or quasi-legal defense in the face of legal risk narrows the scope of triable issues to the accused’s detriment; and on a more basic level, why any accused with any level of legal exposure would make any statement at all. Future iterations of this work will engage with these and other questions in an attempt to understand the forces that shape each statement’s form and content.[104]

III. Emotion and Cognition

In addition to substantive content, we logged the statements’ emotional content, as revealed through the language the accused used, as well as linguistic markers of the accused’s cognitive processes, including authenticity/deception and certainty/tentativeness. Here, we moved from the manual qualitative text analysis process described above—examining each straw in the haystack—to an automated process involving natural language processing tools. We also moved from the phenomenological analysis described above, analyzing what the accused said, to a discursive one, analyzing how they said it.[105]

Our primary tool is a text analysis application called Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC), developed by a team of social psychology researchers at the University of Texas at Austin.[106] LIWC operates by comparing all words in a text—here, each of our #MeToo statements—to a set of dictionaries, or lists of words and phrases.[107] Each dictionary corresponds with a particular emotion, cognitive process, or other topic, and the tool generates a measure of the number of words in each text that are captured by that particular dictionary.[108] In this project, the tool’s dictionaries captured 88% of all words used in the statement set.

LIWC’s dictionary-based labeling of text has been extensively validated.[109] The tool is widely used across a diverse set of disciplines beyond psychology, and is viewed as “the gold standard for many computerized text analysis tasks . . . .”[110] Versions of the tool have been developed to process text written in, inter alia, Dutch, Chinese, Malay, and German.[111]

Using LIWC, we identified each statement’s polarity, meaning the extent to which it expresses positive and negative emotions, including the particular negative emotions of anger, anxiety, and sadness, and the intensity of expression.[112] We also explored the statements’ authenticity (or deception) and certainty (or tentativeness). We then mapped these measures of emotion and cognition onto the substantive content identified above.

A. Emotion: Anger, Sadness, and Anxiety

The statements are, on the whole, negative, angry, and intense. The number of angry statements was double the number of sad ones, and triple the number of statements that expressed anxiety.

Typical high-anger statements include the following three, excerpted in relevant part:

“All I did was annoy liberals. . . . Guilty! . . . I never was accused of anything unethical or illegal, ever. . . . I told a joke to somebody, they overheard it. ‘Oh, I’m offended. I’m offended.’ . . . So in America, the reason you ruin somebody’s livelihood and reputation and everything is, you’re offended?”[113]

“That is an ugly lie I vehemently deny to my core. There is a mountain of proof that also proves it[‘]s a lie. I will fight this like a lion armed with truth. Thanks so much to all those that have reached out in support. #FightingBack. Not surprising media outlets that hate President Trump most put out most twisted stories on me.”[114]

“It’s too stupid to dignify. It’s pathetic lies. It’s just too fucking embarrassing and idiotic.”[115]

Sad statements, in turn, read considerably differently: “To hear that I have caused pain is profoundly upsetting, as is the idea that I might have crossed a line with anyone who considered me a mentor.”[116] “There are no words to express my sorrow and regret for the pain I have caused others by words and actions.”[117] So, too, do high-anxiety statements, which tend to emphasize concepts of guilt and shame.[118]

Statements that LIWC identified as containing positive emotions are relatively rare, but contained forward-looking statements and affirmations about the speaker’s commitment to equality and safety on the job.[119]

Mapping emotional valence onto substantive content, statements with full denials were three times as angry as those without, on average, whereas sadness and anxiety occurred more frequently in non-denial statements. Similarly, statements that contained apologies were an average of one-seventh as angry as those with no apology.

Statements that raised a defense tended to be approximately equally sad and angry. Those that referred to harm to family, friends, and colleagues expressed sadness over the other emotions; statements that contained addiction or mental health narratives tended to be angry as opposed to sad or anxious. Finally, positive emotions appeared most frequently alongside full denials, perhaps because some accused paired denials with ally language and other affirmations.

Measures of intensity followed similar patterns. Here, we constructed an intensity index by tallying adjective and adverb usage, exclamation points, and interjections per statement.[120] Though the statements were all, on the whole, relatively intense regardless of emotional content, the greatest intensity co-occurred with anger, followed by sadness, then anxiety.

These findings parallel the conclusions drawn by another research team in a somewhat similar project: studies of the substantive and emotional content of posts in the online forum Reddit, where anonymous users responded to the prompt, “Reddit’s had a few threads about sexual assault victims, but are there any redditors from the other side of the story? What were your motivations? Do you regret it?”[121]

There, a team of psychology researchers mined the responses for both content and emotion, much as here. Identifying shame, guilt, anger, and depression, that team found strong correlations between anger and denial of responsibility for the assault;[122] co-occurrence of shame and references to “consent confusion and perpetrator alcohol abuse”;[123] and a relationship between guilt and reports of self-growth.[124]

As those researchers note in a pair of articles, the particular cocktail of denial, defense, and anger likely “reduces the likelihood of [the perpetrators] modifying their behavior,”[125] whereas the perpetrators’ “reports of self-growth” combined with markers of guilt may be “a more adaptive response to perpetration,”[126] and may open the door to change. We return to these themes further below.

B. Cognition: Authenticity and Certainty

In addition to emotional expression, we observed markers of two different cognitive processes in the statements. We first address authenticity and deception, and then certainty and tentativeness.

To measure authenticity, and its opposite, deception, we used a dictionary developed by the LIWC research team. As that team explains, authentic and deceptive speech have different linguistic and stylistic attributes. In general, deceptive language contains “(a) fewer self-references, (b) more negative emotion words, and (c) fewer markers of cognitive complexity.”[127] Self-references, through the use of first-person pronouns, signal that the speaker is taking ownership over the speech, an attribute of truth telling, as distinguished from liars’ tendency to dissociate from their fabrications.[128] A greater prevalence of negative emotion words, in turn, may reveal the speakers’ underlying discomfort in lying.[129] Finally, greater cognitive complexity indicates that the speaker is drawing from a well of authentic, real-life detail, rather than having to invent a narrative. For instance, truth tellers are “likely to tell about what they did and what they did not do,” as opposed to delivering a less complex falsehood.[130]

Here, an average of 60% of the statements’ language was marked as authentic. Consistent with the LIWC authors’ explanation of the mechanics of their tool, authenticity scores were highly correlated with a statement’s use of first-person pronouns. Of course, the context in which these statements were generated may pollute these results: public statements by an accused person in response to accusations, by definition, likely contain many “I” pronouns.

However, the distribution of authenticity scores across full admissions, full denials, defenses, and apologies is interesting. The statements that contain admissions register as slightly more authentic than those that do not; statements with defenses score slightly lower than those without. Statements with conditional apologies also score lower than statements with full apologies. The largest difference is between statements with and without denials: the authenticity scores of denial statements are almost 1.5 times lower than those without denials.

Here again, it may be the inherent structure of denials that are generating these results, rather than some extra level of deception practiced by deniers. As shown above, denials co-occurred most frequently with anger, a negative emotion word, and the LIWC tool tracks negative emotion word usage as one component of its authenticity measure. For these reasons, authenticity measures should be taken with a proverbial grain of salt.

A final cognitive process that we measured in the statements is the level of certainty, versus tentativeness, that the accused expressed. As above, certainty aligns more with denials than with admissions, and with statements that contain no apology. This is consistent with intuition: deniers likely want to broadcast as much certainty as possible, and so use declarative, definitive language to eliminate any room for question or doubt. Statements with defenses, in turn, score as more tentative than those without, likely because defense language contains hedge words and modifiers of the type that appear in LIWC’s tentativeness dictionary.[131]

Thus, in sum, the statements were heavily populated by denial and defenses. These responses by the accused were, in turn, angry, certain, and intense. The next Part now turns from mining the statements’ language to reckoning with their meaning. We investigate what the statements tell us about the success of the #MeToo movement in holding individuals to account and making broader structural change.

IV. The Individual and Structural Frames

This Essay uses two frames to assess the #MeToo movement’s success as evidenced by the statements’ text: individual and structural. As described above, the movement began as a series of public accusations of sexual harassment, abuse, and misconduct against individual prominent people.[132] As it has matured, the movement has also begun to take on the project of structural change. As Masha Gessen describes it, #MeToo is shifting from “being a movement aimed primarily at punishing individuals and start[ing] to do its work on the institutions that have enabled them.”[133] Further, to borrow an observation by Kate Manne, #MeToo scholars and advocates “need to try to do justice in our theorizing to both agents and social structures, and also to the complex ways in which they are intimately related.”[134]

What, then, do the statements tell us about both individual and institutional change?

A. Individual

On the individual front, one might measure success in multiple ways. Success might mean a head count of the number of prominent people who have been fired, sued, prosecuted, or forced to resign as a result of #MeToo claims. By that measure, the movement is certainly a failure, as the several hundred people counted by various news outlets comes nowhere near accounting for the 25 to 60% of women who report sexual harassment or unwelcome sexual behavior at work, not to mention the higher rates of harassment experienced by people of color and LGBT and gender nonconforming workers.[135]

Success on the individual front, then, might look less like a tally of punishments meted out and more like a measure of individual growth. Of the people who have been accused, has that experience changed their behavior? Yet on the basis of the statements alone, we have no way of knowing whether the accused are being honest in their denials, admissions, expressions of outrage, and expressions of growth and change. We do not have access to any ground truth (and we cannot rely fully on linguistic measures of authenticity).

However, even if we were to believe the full denials, and focus only on the full admissions and defenses, it is notable that the most common defense—subjectivity–objectivity—takes issue with the basic definition of what counts as sexual harassment.

If growth requires, as Wexler, Robbennolt, and Murphy explain, first acknowledgement and then responsibility-taking, then the statements do not supply much evidence of individual-level progress.[136] Instead, the accused and their accusers are still fighting about what sexual harassment means, operating with divergent sets of legal and factual understandings. These subjective–objective defenses, along with credibility accusations and consent/welcomeness arguments, echo MacKinnon’s observation all too neatly that, before #MeToo, “[c]omplaints were routinely passed off with some version of ‘She isn’t credible’ or ‘She wanted it’ or ‘It was trivial.’”[137]

Turning to the full denials, we assumed above for the sake of argument that all were truthful. Yet we might also assume that at least some denials were false, and that the accused did, in fact, do everything that the accuser alleged, with no room for differing interpretations. Under this assumption, the tenor of the full denials leaves little room for hope.

On the whole, the denials are angry, certain, and intense. As noted above, this profile likely “reduces the likelihood of [the accused] modifying their behavior,”[138] or—more modestly—of moving out of a position of denial and into a position of recognition and understanding.

In sum, then, as Tristin Green points out, the individual frame may be a source of disappointment for #MeToo activists, as the statements reveal a discourse bogged down in divergent understandings, definitional arguments, denial, and anger.[139]

B. Structural

The picture is also relatively bleak on the structural front. Here, rather than individual accountings and punishment, the goal is to change the culture of “open secrets, toxic masculinity, and powerful people getting the benefit of the doubt,” as one commentator describes it.[140] The problem, as Catharine MacKinnon identifies, is that “the more power a man has, the more sexual access he can get away with compelling.”[141] As Kate Manne elaborates, “[s]ome men, especially those with a high degree of privilege, seem to have a sense of being owed by women in the coin of . . . personal goods and services,” including the sexual.[142]

But the structural problem is not just with egregious sexual acts by powerful people. It is also, as Nevada state legislator Lucy Flores and columnist Emma Gray write, in the “subtl[y] undermining” assumption that people’s, especially women’s, bodies are available for seemingly harmless hugging and cheek-kissing, comments and assessments.[143] As Gray summarizes:

When you move through the world with the knowledge that you’ll have to contend with even well-intentioned men violating your boundaries, and you’ll have little recourse when they do, it’s exhausting. These small indignities are difficult to talk about, so for the most part, they go unnamed.[144]

The challenge is thus to “deal[] with wrongdoing that has become normalized.”[145]

Further, the structural problem is not just about sex, but about sexism.[146] Vicki Schultz proposes that we think about sex-based harassment, rather than sexual harassment, to capture experiences like Ellen Pao’s, the Silicon Valley venture capitalist who experienced harassment in the form of a “thousand paper cuts.”[147] As Schultz recounts, quoting Pao:

[Women] were often talked over and interrupted. When we were able to get a word in, we were ignored. If someone liked our ideas, they would repeat them and get credit . . . . Our annual performance reviews cast us as poor team players when we tried to claim credit for our work, and our reviewer lists were often stacked with people who were biased against us. We weren’t invited to meetings, included on emails, asked to interview candidates, selected for hiring committees. We had the seats in the back of the room, the offices in the outer reaches, the non-speaking roles at offsites and conferences.[148]

As noted above, the 219 statements contain hints that some of the accused may be reckoning with their role in perpetuating this set of broader structural and cultural problems. Some statements even contain pledges of remedial and forward-looking action, to reform workplace culture. New Orleans chef and restauranteur John Besh, for example, states:

We have learned recently that a number of women in our company feel that we have not had a clear mechanism in place to allow them to voice concerns about receiving the respect they deserve on the job. I want to assure all of our employees that if even a single person feels this way, it is one person too many and that ends now. . . . [W]e now recognize that, as a practical matter, we needed to do more than what the law requires and we have revamped our training, education and procedures accordingly.[149]

However, many statements, whether they contain admissions, denials, defenses, or apologies, reinforce the accused’s power in ways both obvious and subtle. This reinforcement includes the bolstering moves cataloged above, in which the accused narrate their professional accomplishments, and the attacks on accuser credibility. It also includes Jessica Clarke’s observations about the accused’s claims to extraordinary procedural protections,[150] and Catharine MacKinnon’s analysis of the accused’s references to family as reinforcing their own value.[151]

The statements’ relentless first-person focus, too, subtly emphasizes the centrality of the accused. As described above, the accused often refer to their own subjective perception of their conduct as benign or harmless, without acknowledging the possibility of another interpretation.[152] This elevation of the accused’s perspective is also evident in the statements that touch on consent and welcomeness, where the accused fail to consider, or present a misunderstanding of, the accuser’s position. When accused of making lewd phone calls, groping, and exposing himself to eight female job applicants or subordinates, for instance, Charlie Rose stated, in part, “I always felt that I was pursuing shared feelings.”[153] Rose here substitutes his own unilateral judgment (“I always felt”) for any inquiry into the women’s actual receptivity to his behavior.

The statements’ language also reinforces the primacy of the accused. The descriptive statistics in Part I(B) noted the heavy use of first-person pronouns across the statements. Indeed, 42% of the statements begin with “I” or “My” sentences, many of which describe the accused’s own feelings or reactions to the allegations: “I am devastated . . .”;[154] “I am profoundly disappointed . . .”;[155] “I am deeply saddened . . .”;[156] “I am dismayed . . . .”[157]

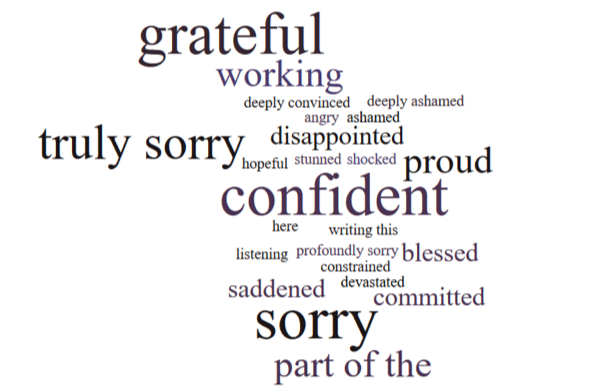

Further, Figure 5 below shows the words and phrases that follow “I am.” While apology words figure prominently, so do expressions of anger, conviction, pride, self-satisfaction, and—tied for first—confidence. These “I am” statements not only place the accused at the center of the #MeToo narrative, but also underline the accused’s power and strength.

Figure 5: Words and Phrases Appearing After “I am” at Least Twice

Thus, while the #MeToo movement may be shifting away from the individual and toward the structural, the accused’s statements reveal the tenacity of the power structures that the movement is attempting to topple, embedded within the accused’s word choices, rhetorical moves, and discursive choices.

Conclusion

This Essay uses both computational and manual qualitative text analytics tools to study 219 public statements issued by people accused of workplace sexual harassment as a result of the #MeToo movement. We find that the statements contain more defenses and denials than admissions and other responses, and that apologies appear in only one-third of statements. We also find the denials and defenses to be angry, certain, and intense.

We then assess the #MeToo movement’s progress toward holding individual perpetrators to account and bringing about larger structural change. We find textual evidence in the statements of challenges on both fronts: the accused and their accusers lack a shared understanding of what counts as sexual harassment law, and the language and structure of the statements tends to reinforce the accused’s own centrality and power.

Though this picture may be bleak, it might also be viewed—more positively—as a road map. The 219 statements provide a window into the accused’s #MeToo understandings, and show the #MeToo movement where work remains to be done.

Modestly, this work might be informative, designed to spread accurate legal knowledge about concepts of consent and welcomeness, as well as due process, where the accused seem to get it wrong. More ambitiously, this work might also be definitional, moving toward a communal understanding of acceptable workplace conduct informed by, but not limited to, sexual harassment law’s definitions.

Finally, and most ambitiously of all, as Wexler, Robbennolt, and Murphy suggest, this work could be transformative, where we overcome our collective denial and normalization of sex-based and sexual harassment as a feature of the workplace, and of society at large.[158] Legal scholar Joan Williams and her co-authors see hints of this already, in what they label a “norm cascade” as super-majorities of Americans now believe that sexual harassment and assault are “important,” and “mainly reflect widespread problems in society.”[159] The 219 statements both show us how far we still have to go, and begin to show us some paths forward.

Appendix A

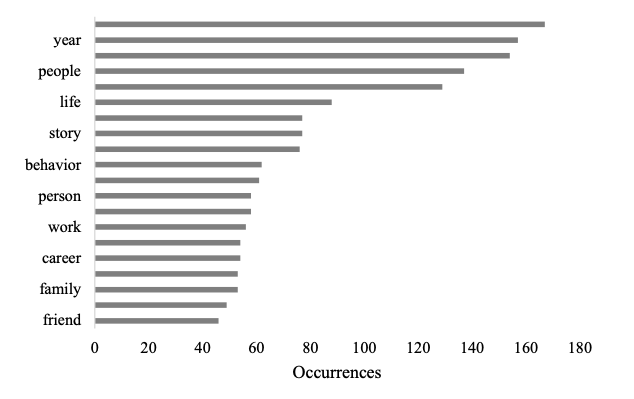

Figure 6: Top Twenty Nouns by Number of Occurrences

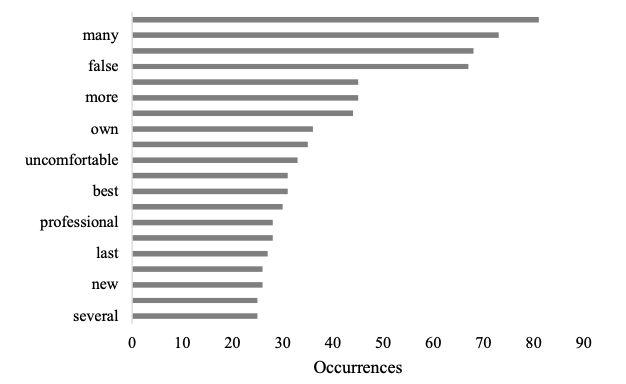

Figure 7: Top Twenty Adjectives by Number of Occurrences

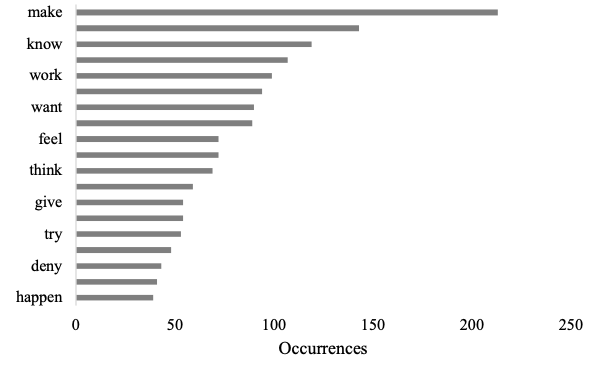

Figure 8: Top Twenty Verbs by Number of Occurrences, Excluding Auxiliary Verbs[160]

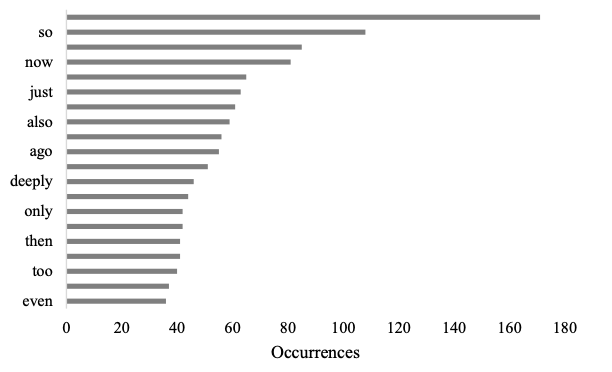

Figure 9: Top Twenty Adverbs by Number of Occurrences

Figure 10: Top Twenty Adverb–Verb Phrases

Appendix B

Table 4: Top Twenty Key Words

- .Sasha Pezenik, In #MeToo Era, Bloomberg’s Comment ‘They Didn’t Like a Joke I Told’ Could Strike a Nerve: Experts, ABC News (Feb. 20, 2020, 7:28 PM), https://abcnews.go.com/

Politics/metoo-era-bloombergs-comment-joke-told-strike-nerve/story?id=69096737 [https://perma

.cc/3D7Q-44CS]. ↑ - .Id. ↑

- .Harvey Weinstein, Statement from Harvey Weinstein, N.Y. Times (Oct. 5, 2017), https://

www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/10/05/us/statement-from-harvey-weinstein.html [https://

perma.cc/MM4P-EK9K]. The accusations against Weinstein launched the #MeToo movement. Jessica Bennett, The ‘Click’ Moment: How the Weinstein Scandal Unleashed a Tsunami, N.Y. Times (Nov. 5, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/05/us/sexual-harrasment-weinstein-trump.html [https://perma.cc/F7E2-5Q2P]. ↑ - .Weinstein was convicted in February 2020 for rape and criminal sexual acts. His lawyer plans an appeal after sentencing in March 2020. Full Coverage: Harvey Weinstein Is Found Guilty of Rape, N.Y. Times (Feb. 24, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/24/nyregion/harvey-weinstein-verdict.html [https://perma.cc/KZ8T-GA42]. ↑

- .Pezenik, supra note 1. ↑

- .See Caroline Framke, Deciphering Harvey Weinstein’s Bizarre Defense Against Sexual Harassment Claims, Vox (Oct. 5, 2017, 4:34 PM), https://www.vox.com/culture/2017/10/5/

16432006/harvey-weinstein-statement-sexual-harassment (analyzing the “series of bizarre defenses” in Weinstein’s statement); Megan Garber, What Harvey Weinstein’s Apology Reveals, Atlantic (Oct. 5, 2017), https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/10/harvey-weinstein-apology/542193/ [https://perma.cc/QC33-KXDT] (calling the apology “a sad—and supremely strange—reminder of how distant true ‘progress’ really is, at this moment in American cultural life, as (some) women advance and as (some) men grapple with that shift”); Janet Eve Josselyn, The Sixties Made Me Do It! Harvey Weinstein’s Excuse, HuffPost (Oct. 5, 2017, 5:40 PM), https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-sixties-made-me-do-it-harvey-weinsteins-excuse_b_59d6a427e4b08ce873a8cc77 [https://perma.cc/32VF-934B] (“It has nothing to do with the ‘60s or ‘70s. It has everything to do with assholes who treat people badly . . . .”). ↑ - .Maureen Dowd, Hollywood’s Most Decent Fella on Weinstein, Trump and History, N.Y. Times (Oct. 11, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/11/style/tom-hanks-uncommon-type-harvey-weinstein-donald-trump.html [https://perma.cc/66ZF-8BWW]. ↑

- .See, e.g., Anne Midgette & Peggy McGlone, In Wake of Post Story About Allegations, an Opera Director Leaves the Field, Wash. Post (Aug. 1, 2018, 2:14 PM), https://www

.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/music/in-wake-of-post-allegations-a-music-director-leaves-the-field/2018/08/01/1fa4477a-95b9-11e8-80e1-00e80e1fdf43_story.html [https://perma.cc/YZA2

-E957] (quoting opera director Bernard Uzan as stating, “I come from a very different culture, I am of the sixties generation, which is not an excuse, but simply a fact . . . .”); Jackie Wattles, Chloe Melas & An Phung, Morgan Freeman: ‘I Did Not Assault Women,’ CNN (May 27, 2018, 1:15 PM), https://www.cnn.com/2018/05/26/entertainment/morgan-freeman-harassment-statement/index.html [https://perma.cc/Q4AG-DR6X] (“I would often try to joke with and compliment women, in what I thought was a light-hearted and humorous way.”); Emily Yoffe, Democrats Need to Learn from Their Al Franken Mistake, Atlantic (Mar. 26, 2019), https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/03/democrats-shouldnt-have-pressured-al-franken-resign/585739/ [https://perma.cc/EJB8-SKT7] (quoting Al Franken as saying about a photo of him pretending to grab the breasts of a sleeping colleague, “[a]s to the photo, it was clearly intended to be funny but wasn’t. I shouldn’t have done it”). ↑ - .Masha Gessen, An N.Y.U. Sexual-Harassment Case Has Spurred a Necessary Conversation About #MeToo, New Yorker (Aug. 25, 2018), https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/an-nyu-sexual-harassment-case-has-spurred-a-necessary-conversation-about-metoo [https://perma

.cc/8746-WD9A]. ↑ - .Tristin K. Green, Was Sexual Harassment Law a Mistake? The Stories We Tell, 128 Yale L.J.F. 152, 167 (2018), https://www.yalelawjournal.org/forum/was-sexual-harassment-law-mistake [https://perma.cc/M9J8-6Y7U]. ↑

- .Vicki Schultz, Open Statement on Sexual Harassment from Employment Discrimination Law Scholars, 71 Stan. L. Rev. Online (2018), https://www.stanfordlawreview.org/online/open-statement-on-sexual-harassment-from-employment-discrimination-law-scholars/ [https://perma.cc/

N945-NKCF] (describing the need to consider harassment and misconduct beyond the man–woman dichotomy). ↑ - .Alyssa Milano (@Alyssa_Milano), Twitter (Oct. 15, 2017, 3:21 PM), https://twitter.com/

alyssa_milano/status/919659438700670976 [https://perma.cc/73DT-6XNX]. This Essay refers to the #MeToo movement, with a hashtag, to identify the series of public accusations made against high-profile figures, often on social media, which launched in October 2017 with a tweet by actress Alyssa Milano. See Sandra E. Garcia, The Woman Who Created #MeToo Long Before Hashtags, N.Y. Times (Oct. 20, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/20/us/me-too-movement-tarana-burke.html [https://perma.cc/T4E3-STKM] (“On Sunday, those two words burst into the spotlight of social media with #metoo, a hashtag promoted by the actress Alyssa Milano.”). We study the public statements that the accused issued in response to #MeToo accusations. However, we also acknowledge the prior, and continuing, work of activist Tarana Burke, who in 2007 established a campaign called Me Too, and a separate nonprofit organization, with a focus on the wellbeing of survivors of sexual abuse, assault, and exploitation, particularly that of young women of color. Id.; see also Tarana Burke, The Inception, Just Be Inc., https://justbeinc.wixsite.com/justbeinc/the-me-too-movement-cmml [https://perma.cc/V2TV-JW2R] (describing the origins of Ms. Burke’s Me Too campaign). Our use of the hashtag is not meant to ignore the contributions of Ms. Burke’s campaign, but rather to focus attention on the particular discourse that has arisen around and in response to public allegations of workplace sexual harassment. ↑ - .Bennett, supra note 3. ↑

- .Audrey Carlsen, Maya Salam, Claire Cain Miller, Denise Lu, Ash Ngu, Jugal K. Patel & Zach Wichter, #MeToo Brought Down 201 Powerful Men. Nearly Half of Their Replacements Are Women, N.Y. Times (Oct. 29, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/10/23/us/metoo-replacements.html [https://perma.cc/49EY-UW4K]. ↑