Rethinking Judicial Review of High Volume Agency Adjudication

Article III courts annually review thousands of decisions rendered by Social Security Administrative Law Judges, Immigration Judges, and other agency adjudicators who decide large numbers of cases in short periods of time. Federal judges can provide a claim for disability benefits or for immigration relief—the sort of consideration that an agency buckling under the strain of enormous caseloads cannot. Judicial review thus seems to help legitimize systems of high volume agency adjudication. Even so, influential studies rooted in the gritty realities of this decision-making have concluded that the costs of judicial review outweigh whatever benefits the process creates.

We argue that the scholarship of high volume agency adjudication has overlooked a critical function that judicial review plays. The large numbers of cases that disability benefits claimants, immigrants, and others file in Article III courts enable federal judges to engage in what we call “problem-oriented oversight.” These judges do not just correct errors made in individual cases or forge legally binding precedent. They also can and do identify entrenched problems of policy administration that afflict agency adjudication. By pressuring agencies to address these problems, Article III courts can help agencies make across-the-board improvements in how they handle their dockets. Problem-oriented oversight significantly strengthens the case for Article III review of high volume agency adjudication.

This Article describes and defends problem-oriented oversight through judicial review. We also propose simple approaches to analyzing data from agency appeals that Article III courts can use to improve the oversight they offer. Our argument builds on a several-year study of social security disability benefits adjudication that we conducted on behalf of the Administrative Conference of the United States. The research for this study gave us rare insight into the day-to-day operations of an agency struggling to adjudicate huge numbers of cases quickly and a court system attempting to help this agency improve.

Introduction

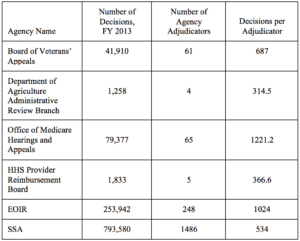

Federal administrative agencies adjudicate huge numbers of cases. Administrative law judges (ALJs) working for the Social Security Administration (SSA), “probably the largest adjudication agency in the western world,”[1] decided 629,337 claims for disability benefits in 2013.[2] That year, the country’s immigration judges (IJs) completed 253,942 “matters,”[3] and veterans’ law judges working for the Board of Veterans Appeals disposed of 41,910 veterans’ benefits cases.[4] ALJs at the Office of Medicare Hearings and Appeals issued 79,377 decisions in cases involving Medicare payments and coverage, an effort quickly swamped by the 384,151 new filings the agency received in 2013.[5] Such immense caseloads require agency adjudicators to work with astonishing speed. The average SSA ALJ decided nearly 540 cases in 2013, or more than two per workday,[6] and the average IJ that year resolved matters for more than 1,000 immigrants.[7] The quality of adjudication often buckles under this furious pace, and criticism for slipshod, inconsistent decision-making has long dogged these agencies.[8]

With their power of judicial review, the federal courts sit atop this mountain of adjudication.[9] Time-strapped agency adjudicators have to rule under conditions hardly conducive to thoughtful deliberation. The fact that a federal judge offers a backstop against arbitrary decision-making thus offers something of a psychological salve.[10] Whatever happens within the agency, so the thinking goes, the unfairly denied disability claimant or the immigrant wrongly threatened with deportation can always get justice in an Article III court. For this reason and others, judicial review is thought to “secure an imprimatur of legitimacy for administrative action.”[11]

But reality intrudes on this appealing view. The availability of judicial review for what we call “high volume agency adjudication”—adjudication by agencies whose caseloads and available personnel limit adjudicators to no more than a minimal amount of time per case—means that the federal courts feed on a sizable diet of administrative appeals. The 7,225 cases immigrants filed in 2013, for instance, accounted for 12.8% of new federal appeals that year.[12] These appeals and others from agencies are indisputably significant to the judicial business of the federal courts.

But is federal court litigation likewise important to harried adjudicators drowning in claims or the agencies that struggle to manage them? The federal courts review only a tiny fraction of the cases agency adjudicators decide—only 3% of SSA ALJ decisions, for example,[13] and only about .03% of decisions by the Office of Medicare Hearings and Appeals.[14] Whatever legitimacy the Article III courts promise must seem like a distant mirage for the vast majority of immigrants, claimants, and others as they litigate in obscure hearing rooms, far away from the grandeur of the federal courts. Doubts that judicial review helps to improve high volume agency adjudication have thus surfaced in administrative law scholarship, perhaps none more importantly than in the seminal studies of social security disability adjudication that Jerry Mashaw wrote in the 1970s and 1980s.[15]

This Article defends the federal courts’ involvement in high volume agency adjudication. It has its roots in our sense of what happens day-to-day in hearing offices, immigration courts, and federal judges’ chambers around the country. We recently completed a two-year study of social security disability benefits litigation, conducted at the behest of the Administrative Conference of the United States.[16] This study required an extensive quantitative analysis of district court decision-making, as well as scores of interviews with agency officials, ALJs and their support staff, federal judges, and private lawyers. It thus gave us a rich perspective on almost every aspect of federal court involvement with the disability benefits adjudication process. A theoretical companion to the report we produced for the Administrative Conference, this Article uses the trove of information we assembled to inform our understanding of what exactly the federal courts can be—and in some instances are—up to when they review decisions issued by overworked, under-resourced agency adjudicators.

Our main contribution is to identify a previously unappreciated function that courts perform when they review high volume agency adjudication. Judges correct adjudicators’ errors, and they forge precedent to regulate agency decision-making. These jobs are well known, although this Article provides a badly needed reassessment of how well courts tackle them. The function not evident to critics of judicial review is a task we call “problem-oriented oversight.” Courts identify and respond to entrenched problems of internal agency administration that can afflict adjudication. When bias discolors an IJ’s decision-making and the agency does not respond, for example, courts can do so effectively. When the SSA issues a guidance document that distorts ALJ orders denying disability benefits claims, the federal courts can push the agency to correct course. Problem-oriented oversight involves more than the correction of adjudicator error or the issuance of precedent-setting opinions. The federal courts use various tools at their disposal to hold agencies accountable and insist that they improve. Added to the other functions federal courts discharge, problem-oriented oversight strengthens the case for Article III review of high volume agency adjudication.

Our argument toggles between the descriptive and the normative. Courts presently engage in problem-oriented oversight. We identify the function and describe how federal judges perform it. We also explain how courts can use a straightforward data gathering and analysis method to conduct oversight more rigorously. Finally, we defend the federal courts’ oversight capacity. Institutional features of courts and agencies limit how well federal judges can correct adjudicators’ errors and regulate agencies through precedent. These impediments pose less of a problem to courts’ oversight function. By relying upon a process that requires aggrieved parties to bring problems to their attention, the federal courts can assemble information about poor agency performance efficiently. Their independence from agencies and Congress enables federal judges to address pathologies afflicting agency decision-making without politics or other agency priorities getting in the way. Finally, the federal courts’ geographic dispersion and prestige make them effective overseers of a sprawling system of agency adjudication, and the sort of data gathering and analysis problem-oriented oversight requires fit within courts’ competencies.

Understanding problem-oriented oversight is important for several reasons. First, appeals from overwhelmed agency adjudicators compose a large chunk of the federal courts’ docket. In 2013, for instance, claimants appealed 18,779 SSA ALJ decisions to federal district courts,[17] nearly equaling federal habeas corpus filings.[18] A fully informed perspective on what Article III judges do on a daily basis requires an appreciation for problem-oriented oversight.

Second, legislators, judges, agency officials, and scholars frequently call for changes to various systems of high volume agency adjudication. Proposals have included the centralization of judicial review in a single Article III court,[19] retrenchment of Article III review,[20] and the end to Article III review altogether.[21] To our minds, problem-oriented oversight, when added to the other functions judges discharge when they oversee high volume agency adjudication, tips an otherwise equivocal normative balance in favor of the current system. But the costs and benefits of judicial review are difficult to measure with precision. Reasonable people may ultimately disagree with our assessment of other functions’ efficacy and what problem-oriented oversight adds to the case they present for judicial review. At the least, however, any suggestion to replace Article III review is incomplete unless it grapples with how the change would affect the federal courts’ capacity to discharge all of the functions they perform, including problem-oriented oversight.

Third, although courts do engage in problem-oriented oversight, some do so unevenly. In certain instances, federal judges have not yet addressed problems of internal agency administration that need a response. Our description and defense of problem-oriented oversight is an attempt to spur courts to execute this function more evenly and aggressively. Finally, problem-oriented oversight is not something exclusive to high volume agency adjudication. Courts have the capacity to perform this function in any domain where they review large numbers of decisions made by other institutions.[22] An appreciation for problem-oriented oversight and how it works can improve the contributions to good government that generalist judges make in a number of fields.[23]

Part I explains why we use immigration and disability benefits adjudication as the two exemplar systems we draw upon in this Article. It also gives brief introductions to both, to provide basic background for the discussion that follows. Part II includes an extensive assessment of the previously identified functions that the federal courts play when they decide appeals from high volume agency adjudicators. Although our reasons differ, we ultimately agree with Mashaw’s influential critique; courts cannot discharge these functions successfully enough to justify the case for Article III involvement in high volume agency adjudication. In Part III, we define problem-oriented oversight and explain how courts engage in it. We also offer a method for data gathering and analysis that courts can use to perform the function more rigorously. Part IV defends problem-oriented oversight through judicial review, stressing the federal courts’ institutional advantages as reasons why the task suits them.

I. Disability Benefits and Immigration Adjudication

A. The Exemplar Agencies

Federal administrative adjudication comes in many varieties. Adjudication by the five ALJs working for the Securities and Exchange Commission represents one variant. They preside over proceedings that often last months and resemble civil litigation in Article III courts.[24] A world apart is a tribunal like the Veterans Administration’s Board of Veterans’ Appeals. Its sixty-one veterans’ law judges decided 41,910 cases in 2013, or 687 per adjudicator.[25] This sort of high volume adjudication poses a distinctive set of challenges. How can large numbers of adjudicators administering the same complex regulatory regime decide cases consistently? How can they render high-quality decisions without allowing a huge backlog of claims to grow? What ensures that adjudicators, worn down by an unending river of cases, do not burn out or become jaded? Finally, can these adjudicators make decisions that will withstand federal judicial scrutiny? Should they be forced to do so?

To assess the contributions federal courts can make to these questions’ answers, we draw on the illustrative experiences of the SSA and the Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR). A number of federal agencies engage in high volume adjudication. Table 1 lists those agencies whose hearing-level adjudicators decide more than one case per workday.[26]

Table 1. High Volume Agency Adjudication

Third, decisions go directly from the SSA and the EOIR to the Article III courts, without some other independent tribunal involved as an intermediary. Before veterans can appeal to the Federal Circuit, they first must litigate before the Court of Appeals for Veterans’ Claims (CAVC), an Article I tribunal independent of the Veterans’ Administration.[31] Adjudicators at the Internal Revenue Service’s Office of Appeals decide more than 40,000 cases each year. Appeals from their orders go almost entirely to the U.S. Tax Court, also an Article I tribunal, before appeals can proceed to a federal appellate court.[32] No such court stands between the EOIR and the courts of appeals, or between the SSA and the district courts, to provide an intermediate level of oversight.We use the EOIR and SSA for several reasons. First, for a long time these agencies have adjudicated more cases than any other.[27] A study of high volume agency adjudication that did not reflect the EOIR’s and SSA’s experiences with the federal courts would offer narrow instruction. Second, both of these agencies generate significant numbers of federal court appeals. Due to a recent spike, ALJs at the Office of Medicare Hearings and Appeals (OMHA) now decide hundreds of thousands of cases each year. Yet very few of the medical service providers contesting a reimbursement decision ultimately seek judicial review. The federal courts received only twenty-seven appeals from OMHA ALJs in 2016.[28] Likewise, veterans appealed only 109 cases to the Federal Circuit in FY 2015,[29] a year the Board of Veterans’ Appeals received 69,957 cases.[30] In contrast, social security and immigration appeals to the federal courts number in the thousands every year. For an agency like the OMHA, judicial review truly is a mirage. For the SSA and the EOIR, it is a more meaningful component in an overall system of adjudication.

Notwithstanding the agencies’ distinctive features, lessons from the EOIR’s and SSA’s interactions with the federal courts can readily inform critical evaluations of other systems of judicial review. Whether direct oversight by Article III courts succeeds should inform judgments of whether an Article I intermediary works better, for instance. Whether Congress should raise or reduce amount-in-controversy requirements for OMHA appeals, to use another example, should depend at least in part on the desirability of judicial review in Article III courts.[33] Also, much of what can be learned from the interactions between the EOIR and the federal courts, or from those between the SSA and the federal courts, does not depend on the precise configuration of judicial review that these systems’ designs involve. The CAVC, for instance, could engage in the sort of data gathering we describe in Part III and use what it assembles to identify and respond to the kind of problems we identify.

B. A Brief Primer on the SSA and the EOIR

The rest of this Article draws upon the EOIR’s and the SSA’s relationships with the federal courts to inform our claims about judicial review and the functions it plays in the context of high volume agency adjudication. Both systems have endless complexities, but a basic orientation to each should suffice for what follows.

As of June 2017, the EOIR, part of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), employed about 325 IJs who work in dozens of immigration courts scattered around the country.[34] Cases can get before IJs in several ways. An immigrant who claims to be fleeing persecution can apply for asylum with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.[35] If USCIS rejects her application, it will forward her case to an IJ for an asylum hearing.[36] Alternatively, the government might initiate removal proceedings against an undocumented immigrant picked up at a work site, or against a noncitizen arrested for a crime. These cases go directly to IJs for adjudication. The IJ holds a hearing and issues a decision on the immigrant’s asylum petition or request for cancellation of removal.[37] If the immigrant loses, she can ask the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA), a sixteen-member appellate tribunal located at EOIR’s headquarters in Falls Church, Virginia, to review the IJ’s decision.[38] The immigrant can appeal from an adverse BIA decision to “the court of appeals for the judicial circuit in which the immigration judge completed the proceedings.”[39]

The SSA’s Offices of Hearings Operations and of Analytics, Review, and Oversight encompass an enormous system of disability benefits adjudication. A person who believes that his impairments prevent him from working applies for disability benefits at one of the SSA’s 1,300 field offices.[40] If initially denied, and if denied again upon reconsideration, the claimant can request a hearing before an ALJ.[41] (From this point on, “ALJ” refers to an SSA ALJ.) The ALJ works with about 1,400 judicial colleagues in one of 160 hearing offices around the country.[42] Aided by a “decision writer,” the SSA’s version of a law clerk, the ALJ issues a written decision after considering the claimant’s medical records, his hearing testimony, and other evidence.[43] If the decision goes against the claimant, he can appeal to the SSA’s Appeals Council, located in the same nondescript Falls Church office building. After a workup by an “analyst,” who also functions as a law clerk, the case goes to one of dozens of appellate adjudicators for a decision.[44] If the claimant loses again, he can appeal to a federal district court, typically the one in the district where he resides.[45]

II. The Justifications for Judicial Review

Disability benefits adjudication belongs as an exemplar in a study of judicial review in part because it has attracted the most exhaustive attention. No treatment of SSA decision-making is more important than the landmark report Mashaw and his colleagues compiled in 1978. They identified several possible functions that judicial review performs, including the following:

- A “corrective function”: courts can correct erroneous agency decisions.

- A “regulative function”: courts can induce agency adjudicators to decide cases more accurately, either through fear of judicial reversal (“the in terrorem effect”) or by forcing them to abide by court-fashioned rules (“the precedential effect”).

- A “legitimizing function”: review of an agency’s decision by an independent judiciary can increase public confidence in the legitimacy of outcomes.

- A “critical function”: courts offer agencies a “steady stream” of feedback that they can use to improve, and that is valuable for its own sake.

- A “public information function”: court decisions “serve as a window on an agency whose operations would otherwise be largely invisible.”[46]

Primarily assessing the corrective and regulative functions, the Mashaw group concluded that judicial review’s benefits for the adjudication of social security disability claims did not justify its costs.[47] Decades later, this claim continues to reverberate in discussions of whether the federal courts should review agency adjudication.[48]

The Mashaw group’s discussion remains the most comprehensive and trenchant analysis of judicial review of high volume agency adjudication. It thus offers a good template for an inquiry into what functions judicial review can serve and how well it can perform them. Revisited four decades later, much of the Mashaw group’s skepticism remains warranted, and not just for disability benefits adjudication. What follows updates and elaborates on the Mashaw group’s analysis, with a focus on judicial review’s error correction, regulative, and critical functions.[49] In any odd instance, the federal courts can discharge one or more of these functions well. But institutional features of courts and agencies prompt doubts that the former can do so reliably enough to place judicial review of high volume agency adjudication on stable normative footing.

A. The Corrective Function

Plenty of appeals filed in the federal courts involve mistakes made by agency adjudicators. To think otherwise requires unwarranted confidence in the internal agency appellate tribunals that stand between first-line adjudicators and the federal courts. Year after year, the SSA requests a voluntary remand in about 15% of cases appealed to the federal courts.[50] These “RVRs” happen only when an SSA lawyer and the Appeals Council conclude that the lawyer cannot defend the ALJ’s decision as compliant with the agency’s own view of social security law and policy.[51] Disability appeals go to the federal courts only after Appeals Council review, so RVRs amount to a concession that internal appellate review sometimes fails.

Errors surely remain for the federal courts to correct, and federal courts surely correct errors. But the Mashaw group doubted that courts can do so reliably. We disagree. Nonetheless, the opportunity cost of court-based error correction unsettles its contribution to the case for judicial review.

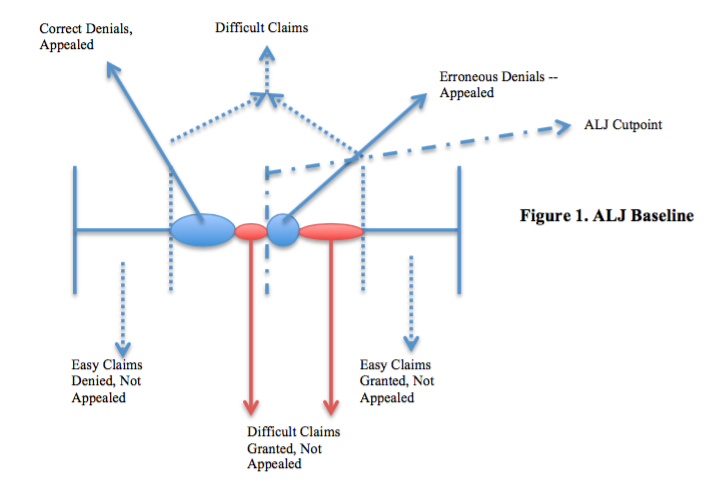

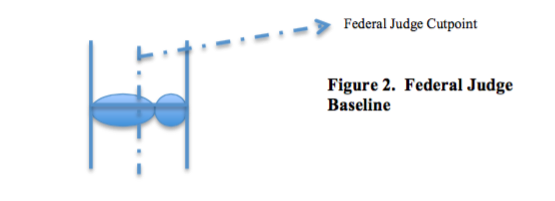

1. The Baseline Problem.—The Mashaw group questioned the capacity of courts to correct errors because of doubts that judges could evaluate disability claims as accurately as ALJs.[52] The problem involves a contrast between courts’ and ALJs’ baselines. ALJs handle a much larger caseload than federal judges, and ALJs get their cases earlier in the adjudication process. ALJs thus see a wider array of types of claims than federal judges do. Moreover, the government cannot appeal, so claimants pick all of the cases that go to federal court.[53] An ALJ may therefore have a different “cutpoint”[54]—roughly, the line the ALJ would draw along a given dimension between disability and no disability—than a federal court for a decision in favor of the claimant. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate.

Figure 1. ALJ Baseline

Figure 2. Federal Judge Baseline

Most appeals presumably come from the groups of correct and erroneous denials of what we call “difficult claims.” Bereft of a more diverse baseline, a federal judge might view what to the ALJ was a relatively weak claim for benefits as an above-average one.[55] “If federal judges saw more of what ALJs grant,” this ALJ told us, “they would appreciate why a case seems more borderline to an ALJ.”[56]

The baseline problem can manifest itself in more granular ways. A federal judge might react differently than an agency adjudicator to particular evidence, for instance. With their immense caseloads, ALJs and decision writers can see letters from the same physicians that use the same phrases to describe patients with strikingly similar problems.[57] “We know which doctors are trustworthy and which ones aren’t,” one ALJ told us, “but we can’t put this in a decision.”[58] Likewise, another ALJ said, “claimants can testify in an obviously coached manner, taught to say just the right thing to buttress a claim for benefits.”[59] IJs may experience the same phenomenon.[60] An ALJ or IJ might correctly discount such evidence, but a federal judge with a narrower evidentiary baseline might fault the ALJ for doing so.

Federal judges have countervailing institutional advantages, however, that may exceed whatever edge a richer baseline gives ALJs. Perhaps most importantly, courts can invest more time and resources in decision-making than agency adjudicators can. To keep backlogs at bay, the SSA asks its ALJs to decide between 500–700 cases per year,[61] with each involving hundreds of pages of medical records and a complex regulatory regime. This caseload is “preposterous,” as one district judge described it.[62] ALJs spend about two-and-a-half hours total on all aspects of a case, and decision writers an additional eight hours when drafting a decision denying a claim.[63] A case gets about four hours of analyst time at the SSA’s Appeals Council, and appellate adjudicators decide five to twelve cases per day.[64]

With 1,000 cases to decide each year, IJs face an even more herculean task.[65] BIA review practices have changed considerably over the last fifteen years, but at their nadir, caseloads gave board members only 7–10 minutes for the average case.[66] Federal judges have more time to deliberate.[67] In FY 2014, when on average a single IJ had more than 1,400 matters on his docket,[68] the entire federal appellate bench received 54,988 filings.[69] Given the governing law’s endless details and the often sizable case files assembled before agency adjudicators, the sheer amount of time a federal judge might spend compared to an ALJ or IJ can compensate for the narrower baseline.

Another institutional advantage adds to the courts’ side of the ledger. The decision-writer-to-ALJ ratio is 1:1,[70] for instance, and the law-clerk-to-IJ ratio is 1:4.[71] District judges have at least two clerks, and court of appeals judges typically have four.

Agency adjudicators’ baselines may give them a better sense of the overall disability landscape than what federal judges enjoy. But the time and resource shortfalls that afflict agency decision-making may make its adjudicators more error-prone, while federal judges’ comparative surfeit of both improves their relative capacity to decide cases accurately. How these advantages and disadvantages balance out is not obvious in the abstract. Not long ago, however, the SSA’s Chief ALJ conceded that it favors the federal courts, observing that “most of our decisions that are remanded or reversed by the federal judges are remanded or reversed simply because our decision did not comply with our own policy.”[72] Although the SSA has embarked upon an extensive program of quality improvement since these comments, the composition of the pool of federal court appeals probably has not changed all that much since that time, as we argue at length in our report.[73] Federal judges can probably identify flawed decisions fairly accurately. The same is likely true of immigration appeals, at least for the cases that the federal courts remand to the agency.[74]

2. The Costs of Mistakes.—Whatever the frequency, surely federal judges err and incorrectly remand cases from time to time. The error-correction function cannot justify judicial review if judges make costly mistakes. Suppose a judge is right eight times out of ten when she remands a case to the agency. Judicial review would prove harmful on balance if the costs of the false positives (the two erroneous remands) exceed the benefits of the true positives (the eight correct ones).

The cost–benefit balance resists an easy assessment in part because the social value and harms of wrongfully made disability payments and of payments wrongfully withheld cannot really be measured.[75] One estimate holds that the wrongful allowance of benefits from 2005–2014 will ultimately cost the federal treasury $72 billion.[76] On the other side of the ledger is an actually disabled claimant whose impairments make a correct decision on her claim “a matter of life and death.”[77] How does the social value of a true positive compare to the costs of false positives?

Any estimate of this balance must necessarily be crude. But one guess suggests that the benefits of true positives basically equal the costs of false positives in the aggregate, at least for social security adjudication, where the likelihood and costs of false positives relative to other categories of high volume agency adjudication are highest.[78] A claimant who successfully obtains benefits can expect to receive about $1,500 in cash per month.[79] In 2007, the Government Accountability Office determined that SSA ALJs eventually grant benefits to 66% of claimants who secure a court remand.[80] We used these numbers together with a range of assumptions about benefits wrongly provided, the costs associated with ALJ time spent on court remands,[81] the social value of dollars received by disability beneficiaries, and the social costs of raising the tax revenue needed to pay for benefits and the operation of the judicial review system, to conduct a back-of-the-envelope cost–benefit analysis. Our calculations yield two key conclusions. First, using what we regard as reasonable values of the key normative and positive parameters, we find that the net social value of judicial review of disability appeals is likely within $10–15 million of zero. Second, even with extreme assumptions in either direction, the net social value or cost of judicial review seems very unlikely to be more than a drop in the bucket when measured relative to the overall magnitude of disability (and federal court) expenditures—almost surely less than roughly a tenth of a penny for every dollar spent on these programs.[82]

3. The Opportunity Cost.—Another way to look at error correction is to consider whether the resources it consumes could be spent in alternative ways. On this view, the limitations of the error correction function lie not only with the difficulties judges have identifying errors, nor only with the harms that false positives cause, but rather with judicial review’s opportunity cost. If invested in agency adjudication, the resources that judicial review requires might lead to fewer errors made in the first instance.

Any adjudication system should prefer error avoidance to error correction, all else equal. An acquittal or dismissal obviously compares favorably to a conviction that later gets vacated on appeal. If the system’s designer has $100 to spend, and if that sum can either avoid one error or correct one error, the designer should invest in error avoidance rather than error correction. Judicial review makes sense from this perspective only if the $100 can buy more error correction than error avoidance.

For social security claims, the return on investment probably comes out in favor of error avoidance rather than error correction. At a minimum, resources expended on judicial review include salaries for the SSA litigators who brief and argue cases, Equal Access to Justice Act (EAJA) fees paid to claimants’ lawyers when their clients prevail,[83] and the cost of federal judge time. In FY 2015, these resources funded a system of judicial review that corrected a maximum of about six-and-a-half errors per ALJ.[84] The SSA paid $38,132,381.48 in EAJA fees in FY 2015.[85] This amount equals the salaries of about 240 ALJs, or 18% of their total number.[86] If spent on ALJs instead, this money alone could increase the ALJ corps by 18% and thereby enable the SSA to lower per capita case completion goals without increasing the backlog of undecided cases. If a lightened load led to even a modest improvement in decisional accuracy, i.e., seven fewer errors per ALJ,[87] then the resources spent on judicial review would yield fewer errors if redirected to error avoidance.[88]

This case for error avoidance rests on the assumption that the federal courts currently correct only a modest number of errors. If the number rises, the argument for an investment in error correction strengthens. In theory, Congress can control this number by resetting jurisdictional requirements and the federal courts’ standard of review. It thereby could adjust the flow of cases to the federal courts. An endogeneity problem seems to exist. Whether Congress should increase the flow of cases to the federal courts depends on the value of the courts’ error correction function. But the value of error correction depends on where Congress sets the dial to control the flow of cases to the federal courts. Also, very importantly, claimants’ behavior might be different earlier in the process if there were no judicial review. For example, some claimants might not pursue appeals at earlier stages if they knew there was no possible appeal to the federal courts, and they might have greater difficulty obtaining legal representation.

Other determinants of the bang for each buck invested in error correction, however, are exogenous. They depend on immutable institutional factors that constrain the federal courts’ overall capacity to review agency decisions. Even under conditions that should prompt the most appeals, the federal courts receive few relative to the agency’s caseload. In 2002, for example, the U.S. Attorney General announced changes to BIA processes to expedite agency review of IJ decisions.[89] Many believe that these “streamlining” changes degraded the BIA’s review considerably by reducing the scrutiny it afforded IJ decisions.[90] BIA remands plummeted,[91] even as IJ decisional quality earned scathing criticism.[92] Cases flooded the courts of appeals,[93] rising from 1,760 in 2001 to 12,349 in 2005.[94] But even at the surge’s peak, only about 5% of IJ decisions produced a federal court appeal.[95]

Attorney incentives are one such institutional factor that limits the federal courts’ docket, regardless of where Congress sets the dial. Immigration and social security lawyers prefer to litigate before agency adjudicators rather than the federal courts. Disability and immigration cases generate only modest fees, so social security and immigration specialists often must have high volume practices.[96] For most lawyers, a federal court appeal takes much more time than an appearance before an IJ or ALJ.[97] Immigration lawyers typically represent clients for a flat fee,[98] an arrangement that should steer them toward less time intensive work (i.e., litigating in immigration court) than more (writing an appellate brief). Lawyers who represent social security claimants likewise have a strong economic incentive to prefer agency work.[99] True, poor quality agency adjudication in some hearing offices may deepen the pool of potentially good appeals and make court work more attractive to lawyers.[100] But as long as lawyers can earn more litigating before IJs or ALJs, the supply of lawyers available to litigate federal court appeals in the areas where agency decision-making suffers may be insufficiently elastic to pick up the slack.

Attrition is perhaps an even more powerful institutional barrier to federal court. The extended process of adjudication and review within the agency can cause even those with meritorious appeals to give up before they reach the federal courts. By the time she can file an appeal in federal court, a disability benefits claimant may well have already spent more than 1,000 days pursuing her claim.[101] Although the time can vary considerably, an immigrant’s case can easily languish for more than 1,000 days before an IJ and the BIA complete their review.[102] Beyond the time involved, carrots or sticks available to the agency can incentivize claimants or immigrants to forego an appeal. Prolonged detention encourages immigrants to eschew appeals and accept removal, presumably to end the misery of incarceration.[103] The SSA allows a previously denied claimant to file a new disability claim based upon a worsening of her condition, but she must abandon any pending appeal to do so.[104]

Finally, the federal courts’ limited capacity to decide appeals in a manner consistent with deliberative judicial practice may ultimately impose an upper limit on how many cases they attract. As filings increase, judicial processes may change to such an extent that they increasingly resemble the fast, truncated adjudication that ALJs and IJs provide.[105] The Second and Ninth Circuits bore the brunt of the surge in immigration appeals after the BIA streamlining changes.[106] Starting in 2002, the Ninth Circuit made aggressive use of a case screening process that ultimately routed sixty percent of immigration cases to staff attorneys for a quick workup, followed by a brief oral presentation of each case to a screening panel of judges.[107] These judges, who typically did not review any materials in advance, decided 100–150 cases based on these presentations over a 2–3 day period.[108] The rate at which immigrants prevailed appears to have fallen sharply between 2002 and 2006.[109] Perhaps this assembly-line character dissuaded some appeals, as lawyers came to identify less of a difference between agency and court adjudication and perceived that increasing caseloads prompt courts to defer more to the agency’s decisions.[110]

B. The Regulatory and Critical Functions

The opportunity cost problem weakens the contribution that the error correction function can make to the case for judicial review. But if courts not only correct errors but also induce agency adjudicators to avoid more in the first place, then its claim to cost effectiveness strengthens. The Mashaw group suggested several ways by which court remands might play such a regulative or critical function. Judicial review might have an in terrorem effect on agency adjudication;[111] adjudicators might follow rules courts fashion, or an agency might use information gleaned from court remands to improve. As before, however, institutional determinants interfere with each of these possibilities.

1. The In Terrorem Effect.—An ALJ or an IJ focused on numbers alone has almost no reason to change her approach to decision-making just because a federal judge might reverse her. Only 2%–3% of ALJ decisions denying benefits produce a federal court remand.[112] The rate for IJs is even lower.[113] Another way to put it is to recall that federal courts remand roughly six cases per ALJ per year, whereas ALJs adjudicate about 540 claims per year.[114] Of course, agency adjudicators may vest outsized stock in the federal courts’ opinions of their work. When ALJs sued to challenge the expectation that each decide 500–700 cases per year as a threat to their decisional independence, for example, their complaint alleged that the slipshod work this case completion goal required “injured” them because it “demeaned” them “in the eyes of the federal judiciary.”[115] To be taken seriously by Article III judges as black-robed colleagues might matter more to agency adjudicators than the odd remand here and there. Thus the threat of federal court review might alter their decision-making.[116]

But federal judge criticism may just as plausibly encourage indifference or hostility among agency adjudicators. For our report, we interviewed ALJs who work in a hearing office that generates few remands and ALJs from a hearing office that generates a lot of remands. The former reported much more positive views of federal court decision-making and commented on the instructional value of court remands; indeed, these ALJs prepare and circulate semi-annual memoranda summarizing all decisions from the district court to which most of their cases go.[117] In contrast, ALJs in the high-remand district complained that district judges have little understanding of or regard for agency processes and expressed no appreciation for district court feedback.[118] The hearing offices there lack any sort of structured process that would internalize learning from district court opinions.[119]

2. The Precedential Effect.—Any in terrorem effect or lack thereof is less significant if a court can impose precedent on the agency that forces it to improve. This “precedential effect” has long attracted criticism on grounds that generalist courts lack the requisite expertise and perspective to forge useful legal changes to a complex regulatory regime.[120] We take as a given the proposition that judges can craft wise opinions for these areas of law, a proposition that is necessary but not sufficient for the precedential effect to function. Regardless of this proposition, however, institutional features and incentives can render the actual effect of precedent on agency decision-making questionable for high volume adjudication.

First, reviewing courts might not have a lot of precedent-setting authority. This is clearly true when appeals first go to the federal district courts, whose decisions agencies can ignore as nonprecedential. It can also be true when courts of appeals review agency decisions, because an agency can narrow the range of issues for which the court can issue binding precedent. If an internal appellate tribunal issues an opinion that resolves an unsettled interpretive issue, as the full BIA does routinely,[121] courts must extend the decision deference if it meets certain criteria of authoritativeness.[122] An agency can control the lawmaking terrain even more completely by issuing legislative rules.[123]

Second, agencies can resist control by judicial precedent when it does issue. Whether an agency can formally do so poses a complicated question, although the answer is probably no. To a greater or lesser degree, a number of agencies at one time or another have asserted a policy of “nonacquiescence,” whereby they reserve the right to treat appellate case law as nonbinding.[124] “Intercircuit nonacquiescence,” by which precedent binds adjudicators only within a circuit’s boundaries, is routine.[125] This practice necessarily weakens the power of judicial review to regulate agency behavior,[126] but no more than how circuit boundaries limit the force of any precedent. The Fourth Circuit cannot compel ALJs in Pasadena to follow its interpretation of the Social Security Act, but neither can the Fourth Circuit demand that police officers in Pasadena honor its understanding of the Fourth Amendment. The Supreme Court has never ruled on “intracircuit nonacquiescence,” the more problematic variant, whereby an agency denies that appellate precedent binds its decision-making even within that circuit’s boundaries. The lower federal courts have uniformly condemned the practice,[127] and neither the EOIR nor the SSA currently practices intracircuit nonacquiescence, at least formally.[128]

But acquiescence in judicial precedent does not necessarily happen automatically within an agency. The agency typically has a process to digest case law that, whether intentionally or unintentionally, can blunt the precedent’s force. When a court of appeals issues a published opinion that goes against the government in an immigration case, the EOIR’s Office of General Counsel must coordinate the agency’s response with the DOJ’s Office of Immigration Litigation and its own Office of the Chief Immigration Judge.[129] This “difficult” process[130] presumably can delay the opinion’s effect on IJ adjudication.

Something more than the unavoidable difficulty of bureaucratic coordination seems afoot in the SSA. Since 1985, the agency has required all ALJs within a circuit to follow that circuit’s precedent.[131] But ALJs do not simply read opinions on their own and decide whether and how a court has tweaked agency policy. The SSA instructs ALJs to ignore circuit decisions until the agency has determined that the decision conflicts with agency policy. Only then does the SSA issue an “acquiescence ruling” that directs ALJs to comply.[132] This threshold can cloak a de facto policy of intracircuit nonacquiescence. The agency can soft-pedal differences between precedent and its own policy, insisting that no conflict exists, and thereby instruct ALJs to ignore court decisions. In 2013, for example, the Fourth Circuit held that ALJs must give “substantial weight” to the Veterans Administration’s disability determination when a claimant with prior military service seeks social security benefits.[133] The social security ruling on the subject at the time was that the VA’s determination “cannot be ignored and must be considered,” an obligation that on its face seems weaker.[134] But the SSA never issued an acquiescence ruling for the Fourth Circuit’s opinion.[135] In fact, the agency has issued just over eighty acquiescence rulings during the acquiescence policy’s thirty-year history.[136] After an initial flurry of acquiescence rulings in the 1980s, when the policy began, the SSA’s pace has slowed markedly. Since 1990, the SSA has issued only three acquiescence rulings for the Second Circuit, for example,[137] and only three for the Seventh Circuit—a court that generated at least ten published opinions adverse to the agency in 2015 alone.[138]

The tactics agencies can use to limit case law’s significance matter less if agencies have no reason to resist regulation by precedent. But they do, for several reasons. First, agencies may believe that generalist courts inexpertly craft doctrine. Second, circuit-specific precedent can interfere with an agency’s effort to administer a single national policy uniformly across the country.[139] An agency may believe that justice lies in the consistent treatment of regulated entities or beneficiaries, regardless of what courts say in different parts of the country.[140] Also, the administration of a policy that splinters into dozens of geographically determined variants, to be applied by hundreds of different adjudicators, could prove impossibly difficult to administer. ALJs and IJs have earned harsh criticism for decisional inconsistencies.[141] While IJ disparities remain stubborn and notorious,[142] the SSA has undertaken significant efforts to identify reasons for ALJ idiosyncrasy and to counteract them.[143] If the SSA instructed ALJs to abide by circuit and district precedent, the agency would invite ALJs to draw their own judgment about governing policy and complicate its efforts to get more than 1,000 adjudicators on roughly the same policy-compliant page. For this reason,[144] the SSA has instructed ALJs and decision writers “not to consider any district court decisions.”[145]

If an agency is recalcitrant, Congress can structure judicial review to maximize courts’ power to create a precedential effect. As some have proposed for social security disability claims litigation, Congress can require that appeals go directly to circuit courts, not district courts, and it can steer all appeals to a single circuit.[146] Doing so would undermine a key argument for nonacquiescence: that different instructions from geographically dispersed courts would flummox an agency’s effort to administer a single national policy. But this arrangement would require either significantly less litigation, a dramatic change to judicial standards for acceptable decision-making, or a huge increase in the size of the designated appellate court. When Congress contemplated legislation to send all immigration appeals to the Federal Circuit, the Federal Circuit’s chief judge estimated that judicial time for decision-making would plummet to an hour-and-a-half per case as a result.[147] Were Congress to centralize all of the disability appeals currently pending before the regional circuits in the Federal Circuit, its caseload would spike by 25%, assuming no changes in claimant behavior; if all disability cases pending before the district courts went to the Federal Circuit, the latter would have to grow by dozens of judges to keep its caseload at manageable levels.[148]

3. Feedback.—Whether binding or not, court decisions can serve as a valuable source of feedback and thereby discharge a critical function. An agency can always examine its wins and losses in court to look for ways to improve. But several institutional contrasts between courts and agencies may reduce agency incentives to do so.

One involves institutional goals. On a superficial level, agencies and courts share the same goal: the accurate and efficient implementation of the relevant regulatory regime. On another, however, these goals diverge. Agencies attempt to meet standards for decisional quality, but quantity—case completion goals, production quotas, and so forth—matter just as much, if not more, in measures of agency performance.[149] Quality conflicts with quantity, for obvious reasons.[150] ALJs surely could generate better decisions with half as many claims to adjudicate, but claimants would then wait twice as long for a hearing. The SSA is legitimately concerned with the injustice of a claim’s being unreasonably delayed.[151] It faces constant and enduring scrutiny for its claims backlog,[152] as does the EOIR.[153]

Agencies have the complex task of successfully managing the tradeoff between quantity and quality. Typically, the federal courts do not shoulder the same obligation to generate large numbers of decisions quickly.[154] Agencies constantly monitor adjudicator productivity and evaluate performance in terms of it.[155] The institutional culture of the federal judiciary would not permit the same sort of pressure on individual judges.[156] Moreover, the federal courts do not endure the same legislative and public scrutiny for their pace of decision-making that agencies routinely confront. Federal judges can therefore render particularized justice tailored to the circumstances of an individual case without significant regard for production quotas. Differences in resources available to decide cases exacerbate the significance of these contrasting goals. An ALJ deciding up to fifty cases per month has a fundamentally different job than a federal judge and her clerk, who can deliberate on a case for a week.[157]

An agency adjudicator might treat judicial feedback as unhelpful if it does not account for her need to produce decisions quickly under severe resource constraints. An example involves the enforcement of subpoenas ALJs issue to medical providers for relevant records.[158] To some federal courts, especially in pro se cases, the mere issuance of a subpoena does not discharge the ALJ’s obligation to “develop” the record[159] when the person or entity being subpoenaed does not respond.[160] An ALJ who seeks a subpoena’s enforcement, however, must trigger a cumbersome, time-intensive process.[161] The SSA may follow through on a particular court remand requiring a subpoena’s enforcement. But the agency is not likely to act on this feedback more generally and institutionalize a subpoena enforcement policy, given the demands of its caseload.[162]

A second institutional difference might affect the filter through which adjudicators view court feedback, countering its potency. Agency adjudicators might feel obliged to honor aggregate-level, agency-wide policy goals that courts do not countenance.[163] A need to “protect the fund” and the overall health of the social security program might influence ALJ decision-making in individual cases.[164] Observers have long commented on the uncomfortable placement of IJs within the DOJ, suggesting that this institutional arrangement may skew decision-making in favor of strict enforcement.[165] Federal judges face no such aggregate-level pressure for the successful administration of a complex regulatory regime.

Two other institutional differences can also undermine guidance derived from judicial opinions. The first is the baseline problem described above. A nitpicky remand of a clearly meritless claim might lead the ALJ to discount the district court’s order, and perhaps future ones, as uninformed. Second, the agency might explicitly discourage its adjudicators from considering court remands as a source of feedback, concerned that doing so might create discrepancies in adjudicators’ understandings of policy-compliant decision-making.

Whatever the reason, the SSA presently does little as an agency[166] to mine district court remand decisions for instruction. An ALJ who gets remanded will see the decision, but the decision writer who drafted it will not.[167] Neither does the Appeals Council analyst nor the appellate adjudicator. The EOIR has no mechanism in place to ensure that staff attorneys involved in a decision that gets remanded see the court opinion and learn from it.[168]

* * *

The foregoing dwells on the many institutional impediments that interfere with judicial review’s corrective, regulative, and critical functions. The story may not be quite so bleak. In particular instances courts may discharge one or more of the functions more successfully. The body of immigration law that IJs administer, for instance, owes a good deal to federal circuit precedent. Also, the case for judicial review should not depend upon the justificatory force of any single function in isolation but rather the cumulative contributions that courts can make. Courts may not correct errors more efficiently than adjudicators can avoid them, but if they can rectify some mistakes and exert some regulative influence, however limited, then perhaps the case for judicial review of high volume agency adjudication strengthens.

Those who have studied high volume agency adjudication most closely remain unconvinced. The Mashaw group favored the replacement of Article III review of ALJ decision-making with a specialized social security court,[169] a recommendation seconded by distinguished commentators.[170] When Congress caved to judicial pressure and created judicial review for veterans benefits adjudication in 1988, it opted for a specialized Article I court.[171] A proposal to jettison review of IJ decisions by the regional courts of appeals gained traction in Congress in the mid-2000s.[172] Many clearly continue to believe that whatever benefits Article III review brings to high volume agency adjudication, they fall short of justifying it.

III. Problem-Oriented Oversight

Judgments about judicial review’s wisdom are incomplete because existing accounts of its role supervising high volume agency adjudication have overlooked a key function courts can perform. This function has something important to do with an interesting dynamic apparent in the case law this litigation generates. Often boring and repetitive, appeals typically yield cookie-cutter opinions of little significance.[173] Not infrequently, however, judges break this tedium with extraordinary commentary on patterns or trends they have observed. Identifying a set of ALJ decisions he found troubling, for example, a magistrate judge recently described some social security proceedings as “border[ing] on madness.”[174] In a separate opinion released the same day, he denounced ALJ decisions as “littered with recurring issues” and lampooned social security appeals as “Groundhog Day.”[175] Perhaps such statements, which are legion in immigration opinions[176] and not uncommon in social security cases,[177] are little more than outbursts of judicial frustration. But Article III judges tend to keep their powder pretty dry, so we interpret this sort of commentary as purposeful.

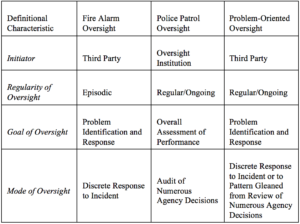

From time to time, judges try to influence agency decision-making through means beyond the correction of discrete errors in individual cases or the issuance of binding precedent. A comparison provides some insight into what courts might be up to. Congress has a lot of tools at its disposal to influence agency behavior.[178] One important one is a form of oversight, by which legislators assemble information on an agency, then comment publicly and critically on its performance.[179] Although in theory backed by the threat of a budget cut or some other legislative sanction, these congressional interventions can derive force simply from the informal pressure they generate.[180] We argue that courts attempt something similar, what we call “problem-oriented oversight,” when they decide certain appeals.

Courts engage in problem-oriented oversight when they identify and respond to “problems,” defined either as flawed administrations of policy by the agency, or as the agency’s nonresponse to an entrenched decision-making pathology. This Part distinguishes problem-oriented oversight from existing models of agency oversight and explains how courts engage in the task. Part IV examines the institutional factors that determine whether this function can succeed.

A. Models of Agency Oversight

The notion that judicial review functions as a type of agency oversight is hardly novel.[181] What exactly this oversight is and how courts conduct it in the context of high volume agency adjudication, however, have attracted little examination.

We begin with what Mariano-Florentino Cuellar aptly calls an “incredibly durable framework for thinking about legislative oversight of the bureaucracy,”[182] a subject that has garnered more study than court-based oversight. This canonical framework describes oversight in terms of two models.[183] When Congress engages in “police patrol oversight,” it surveys a large number of agency decisions or actions, selected at random, to determine if the agency is functioning properly.[184] Like a police officer cruising a neighborhood, this oversight happens when, “at its own initiative, Congress examines a sample of executive-agency activities, with the aim of detecting and remedying any violations of legislative goals and, by its surveillance, discouraging such violations.”[185] Police patrol oversight is proactive and often regular and ongoing.[186] Examples include making an agency submit annual reports to Congress, obliging agency officials to appear at committee hearings in connection with an annual budget request, and submitting an agency to examination by the Government Accountability Office.[187]

“Fire alarm oversight,” the second model, responds to institutional constraints, including high costs and inconstant legislator attention, that in theory limit the efficacy of police patrols.[188] Rather than itself gather and sift through large amounts of information about agency performance to find possible problems, “Congress establishes a system of rules, procedures, and informal practices that enable individual citizens and organized interest groups to examine administrative decisions . . . , to charge executive agencies with violating congressional goals, and to seek remedies from agencies, courts, and Congress itself.”[189] Such mechanisms are “fire alarms” that third parties can ring and thereby direct oversight attention to agency misconduct. Thus, this oversight is episodic and reactive.

A recent disability benefits scandal nicely illustrates fire alarm oversight. David Daugherty, an ALJ in Huntington, West Virginia, granted benefits in 1,280 of the 1,284 cases he decided in FY 2010.[190] This was the sixth year in a row in which Daugherty had decided more than 1,000 cases;[191] it came amidst a stunning growth in the nation’s disability rolls, and in a year when ALJs granted benefits in more than 70% of cases they decided on the merits.[192] Protected by a statutory safe harbor,[193] a prototypical fire alarm,[194] a whistleblower contacted the Wall Street Journal to bring Daugherty’s practice of rubber-stamping disability benefits claims to light.[195] The article prompted several congressional hearings[196] and at least two committee reports.[197] What emerged was criticism that the SSA, focused on case-completion goals above all else, turned a blind eye to ALJs “paying down” a huge backlog of claims.[198] Daugherty eventually pleaded guilty to felony charges, admitting that he took kickbacks from a local social security lawyer who received fees when Daugherty granted his clients’ claims.[199] Although the SSA denied the blind-eye charge, it made significant changes, at least partially in response to congressional scrutiny.[200] The ALJ claim allowance rate declined sharply, to 48%, by 2013.[201]

Although developed to describe versions of Congressional oversight, the police patrol and fire alarm models have come to serve as descriptions of how a range of overseers, including courts, can supervise agencies.[202] Judicial review has traditionally been treated as a component in a fire alarm system, with courts either as the oversight institution itself, or with courts serving as a forum where aggrieved third parties can ring a fire alarm and thereby trigger oversight.[203]

B. The Limits of the Fire Alarm Model

When Richard Posner castigated the “Immigration Court” as “the least competent federal agency” in a 2016 opinion,[204] perhaps he meant his harsh words as an attempt at fire alarm oversight. A third party, the immigrant facing removal, brought an alleged agency problem to a court and got Judge Posner to respond vociferously. But for several reasons the fire alarm model imperfectly describes what courts do. First, courts review large numbers of cases, most of which were either acceptably decided or at worst marred by random error. Fire alarm oversight is premised on the notion that third parties screen agency decisions for the overseer, finding agency flaws for a court, or a legislature motivated by a court, to fix. If this is so, the mechanism would seem to fit high volume agency adjudication poorly. Indeed, judicial oversight has some of the markings of a police patrol. It is regular and ongoing, and it involves large numbers of unremarkable agency decisions.

The ordinariness of judicial review relates to a second reason why it does not really serve as a form of fire alarm oversight in the context of high volume agency adjudication. To the extent that fire alarm oversight depends upon attracting the attention of Congress or the public at large, the regularity of court involvement interferes with the objective. We are unaware of any congressional hearings held during the past decade that court decisions in social security cases prompted, even as federal judges have fulminated about poor quality SSA decision-making.[205] If fire alarms ring all the time, then they seem less like alarms and more like background noise.

Finally, especially for the sorts of problems that courts are uniquely well-positioned to identify and to try to correct, effective judicial oversight of high volume agency adjudication is often not reactive and incident-driven, but requires judicial proactivity and extended engagement over time. Sometimes an appeal from a random ALJ or IJ order sounds the alarm over a large-scale matter whose significance a court immediately appreciates. When the BIA determined that someone seeking asylum based on her experience with female genital mutilation did not establish a risk of future persecution because the mutilation happened in the past,[206] the Second Circuit swiftly rebuked the agency for a “significant error[] in the application of its own regulatory framework.”[207] But an array of smaller bore but nonetheless important pathologies, such as problematic behavior by a single adjudicator or flaws in an agency’s internal manual, can plague agency decision-making. Judicial awareness of these problems might sharpen only over time, and only as courts engage repeatedly with them.

C. Problem-Oriented Oversight Through Judicial Review

Judicial review of high volume agency adjudication does not fit the police patrol model either. The process relies upon third parties to identify and complain about flawed agency decision-making, which is a defining feature of fire alarm oversight. Courts do not proactively seek out adjudicator orders to review, as an auditor randomly sampling decisions to get an overall sense of the agency’s performance might.[208] But an adjusted version of the police patrol metaphor works pretty well to describe the oversight role that courts can assume. “Problem-oriented policing”

posits that police should focus more attention on problems, as opposed to incidents . . . . Problems are defined either as collections of incidents related in some way (if they occur at the same location, for example) or as underlying conditions that give rise to incidents, crimes, disorder, and other substantive community issues . . . .[209]

Whereas “incident-driven,” reactive policing focuses on the resolution of discrete incidents,[210] problem-oriented policing treats each incident as a datum for the identification of underlying factors that create crime and for the best possible responses.[211] Identifying underlying causes, not clearing arrests, is the goal.[212]

Table 2 describes definitional characteristics of fire alarm, police patrol, and problem-oriented oversight.

Table 2. Models of Oversight Compared

When courts engage in problem-oriented oversight, they treat appeals as indicators of potential problems. Of course, many appeals simply result from adjudicator “error,” a word we use as a term of art. But “problems,” defined as systematic underlying pathologies in internal agency administration that afflict adjudication, can lurk among these flaws. The claimant or immigrant bringing the problem to a court’s attention may not know whether his case presents an error or a problem. Precisely the ordinariness of judicial review, or the continuing, routine engagement of courts with the agency’s decision-making, enables courts to distinguish problems from errors and respond appropriately.

1. Errors.—Agency adjudicators can produce flawed decisions for several reasons. Sometimes they simply err. The agency has adopted an acceptable interpretation of governing law. An acceptably competent adjudicator understands and applies this interpretation. But in the odd case, the adjudicator, as a mere mortal, happens to make an error. Perhaps amidst the six hundred pages of medical records in the claimant’s file, an ALJ overlooks the physician’s note that confirms a claimant’s alleged symptoms.[213] Perhaps the IJ wrongly but not unreasonably treats a particular conviction as a “crime involving moral turpitude,” which requires the immigrant’s deportation.[214]

When an agency adjudicator errs, a reviewing court can correct the error but accomplish little more. By our definition of error, no underlying problem exists to address. Presumably, the ALJ would have decided the case better had she caught the physician’s note, and the case proceeded to federal court only because her mistake slipped past personnel at the Appeals Council. As we have already argued, this error correction offers a marginal justification for judicial review of high volume agency adjudication. To return to the metaphor, the error-correction function is like arresting a random lawbreaker, not ferreting out what underlying factors foster criminal activity.

2. Problems.—Flawed decisions result from problems, not mere error, in one of two situations. First, the agency may have adopted a bad policy. Second, the agency cannot or will not fix an entrenched decision-making pathology.

a. Bad Policy.—Agencies can adopt bad policies. The BIA’s erstwhile stance on female genital mutilation is an example. An instruction in a guidance document or manual that conflicts with governing precedent is another, albeit one more likely to fly under the radar and less likely to trigger a loud fire alarm.[215] However fine the mesh in its net, an internal appeals tribunal would never catch flawed adjudicator decisions when the shortcomings result from a bad policy because the tribunal has to abide by the policy as well. Thus, it would uphold an adjudicator’s decision following the policy as correct.

b. Entrenched Pathology.—A second type of problem results when the agency is unwilling or unable to correct an entrenched pathology that afflicts adjudicator decision-making. The threat of deliberate indifference to certain strains of adjudicator dysfunction lurks in the institutional DNA of agencies tasked with large numbers of claims or decisions to make. The number of cases decided is an easily administrable performance metric, but one that can reward decision-making that fares poorly by the harder-to-use measure of decisional quality.[216] If an agency sets production targets or quotas, as the EOIR and SSA do, it may find the temptation to ignore warning signs of serious adjudicator dysfunction overwhelming.[217] Judge Daugherty, the Huntington ALJ, had a shockingly high allowance rate and decided astonishing numbers of cases. Together with the $600 million in lifetime benefits he awarded,[218] these dubious achievements should have raised red flags in SSA headquarters.[219] Instead, notwithstanding a well-documented morale and management problem in the Huntington hearing office, the SSA, under pressure to keep a growing backlog at bay,[220] transferred 1,186 aged cases there between 2006 and 2011.[221] During this time, the SSA based its evaluations of ALJ performance solely on number of cases decided, with no adjustment for decisional quality.[222]

The Huntington episode did not trigger judicial review because the SSA generally cannot appeal when an ALJ grants benefits. But an agency focused on numbers might just as well turn a blind eye to poor-quality decision-making that harms claimants or immigrants if the adjudicator decides a lot of cases.[223] The Atlanta immigration court decides cases in immigrants’ favor at astonishingly low rates.[224] Persistent criticism for perceived bias against immigrants hounds Atlanta IJs,[225] and at least one Atlanta IJ has attracted a disproportionate number of formal complaints.[226] But, as an observer speculates, the EOIR has not taken significant steps at reform, perhaps because the Atlanta immigration court decides large numbers of cases.[227]

Entrenched pathologies might persist for reasons other than deliberate indifference, but ones equally baked into the institutional structure of agency adjudication. Agency adjudicators often enjoy employment protections that amount to a minor league version of life tenure.[228] The SSA cannot take disciplinary action against an ALJ based solely on how the ALJ decides cases,[229] and its power to force ALJs to manage their cases in particular ways is tightly constrained.[230] An ALJ bears almost no risk of termination.[231] Indeed, the SSA believes that it cannot suspend an ALJ without pay, much less terminate him, until that ALJ has exhausted his appeals before the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB).[232] This extended process can create considerable delay.[233] After pleading guilty to a felony charge, for example, an ALJ who had sexually assaulted an employee in a hearing room during work hours while intoxicated received his salary for three more years until the MSPB had finally finished its review.[234]

Such protections, a (lesser) version of which IJs also enjoy,[235] give agency adjudicators a plausible claim to independence.[236] But they can lead to inertia or conflict avoidance within the agency and slow down or arrest efforts to respond to decision-making pathologies. Notwithstanding repeated federal judicial criticism of his performance,[237] for instance, one ALJ remained a hearing office chief administrative law judge until a class of 4,000 denied claimants filed a lawsuit against the SSA, alleging that due process violations systemically plagued his and several colleagues’ case management.[238] Only upon the lawsuit’s filing did the SSA relieve the ALJ of his management role.[239]

3. Distinguishing Errors from Problems.—To succeed as overseers, courts have to be able to distinguish problems from errors. Sometimes the former are obvious. A sharp uptick in court remands suggests something more systematic afoot than idiosyncratic adjudicator error. When the SSA terminated disability benefits for hundreds of thousands of claimants in the early 1980s,[240] appeals flooded the courts, and the court remand rate jumped from 19% in 1980 to nearly 60% in 1984.[241] The SSA’s problematic policies with regard to mental impairments and continuing-disability review quickly became obvious.[242] Likewise, if sufficiently awry, even a single flawed decision can suggest an entrenched pathology. The Ninth Circuit described an IJ’s decision denying asylum in a 2005 case as “a literally incomprehensible opinion,” “indecipherable,” and “extreme in its lack of a coherent explanation,”[243] flaws that loudly signaled a troubled adjudicator.[244]

In many instances, however, problems manifest themselves less clearly. These are ones where the bad policy or the entrenched pathology is subtler, and thus demonstrates its faults only over time. The SSA provides ALJs with a digital template that generates boilerplate for decisions. Before 2012, this text included a poorly written paragraph that presented an ALJ’s findings in a manner that suggested that the ALJ had improperly assessed the claimant’s credibility.[245] This flawed boilerplate is an example of a bad policy. But it is one whose demerits as such—that is, as a policy and not a random error—would likely become evident only as courts saw the same boilerplate over and over again.

Courts catch problems of this scale by reviewing large numbers of cases, identifying patterns of flaws, and determining that something more than random error creates them. What follows is a highly stylized description of this process, one that no court of which we are aware actually uses. It owes a debt to a method the SSA has pioneered, using Appeals Council data to find problems in ALJ decision-making.[246] We believe it illuminates the mental steps courts proceed through as they identify problems. We present the method here to argue how courts should oversee high volume agency adjudication, and then defend their capacity to use it in Part IV.

The first step involves devising the proper classifications of potential problems. As with problem-oriented policing, broad classifications are “too heterogeneous” to yield much information about agency adjudication,[247] a claim we elaborate upon at length in our report.[248] Problem-oriented policing uses “highly nuanced and precise problem definitions.”[249] To understand what factors generate burglaries in Tucson, Arizona, for example, the police should not just keep track of “burglaries.” Instead they should also gather data on “burglaries in college dormitories,” “burglaries in neighborhoods with alleyways,” and so forth.

Problem-oriented oversight through judicial review should do the same. In the social security context, for example, courts should identify potential problems not as “remands,” or even “remands to the Brooklyn Hearing Office.” Rather, courts should develop categories that can identify flawed policies at the level of detail at which the agency crafts it, and they should use categories that can identify entrenched pathologies at the level at which they fester. The problems might be “treating source – opinion rejected without adequate articulation,” or “inadequate rationale for credibility finding.”[250] The entrenched pathology category might track decisions at the individual ALJ level, and certainly at the hearing office level.

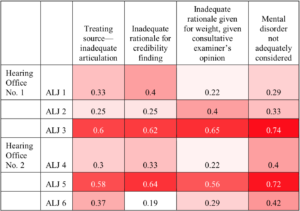

To identify patterns and thus potential problems, courts could then use problem definitions to map data gathered from decisions. For any particular judicial review context the map would differ and depend on courts’ sense of where problems likely will come from and how they might materialize. Table 3 tracks reasons for remands from judges in the hypothetical District of East Dakota over a three-year period. It offers a simple illustration of how a federal district might organize data capturing arguments made and reasons given in social security cases.

Table 3. D.E.D. Remands as a Percentage of Appeals,

by Reason Given, FY2014–2016

The district would then organize data on its judges’ decisions, to see if they suggest any particular problems. The number in each of Table 3’s cells is a fraction, indicating how often a court concludes that a particular ALJ’s decisions contain particular flaws. The numerator represents the number of cases in which the court agrees that the ALJ’s decision contains the flaw, and the denominator is the number of cases in which the claimant argues that the ALJ’s decision contains the flaw. Organized thusly, the data yield a heat map that highlights potential problems. Table 3, for instance, indicates that ALJs 3 and 5 produce unusually high numbers of remands, regardless of the alleged flaw, and have done so consistently. Their decisions’ high rate of failure across the board may suggest adjudicator dysfunction, and its persistence over multiple years may indicate an entrenched pathology that the agency cannot or will not correct.Table 3 breaks down reasons for remands into more precise categories that may correspond to detailed policy decisions the agency might make. The SSA, for instance, might urge its ALJs to assess credibility in a particular manner, or to use a particular approach to considering mental impairments. These policy determinations should show up in arguments claimants make for remands and reasons courts give for ruling in their favor. Table 3 also recognizes the possibility that a particular ALJ might be deciding cases in a pathological way, or that a particular hearing office suffers from pathological management.

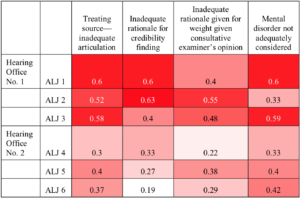

Table 4 gives an example of a heat map that indicates an entrenched pathology at the hearing office level.

Table 4. Hearing Office Pathology

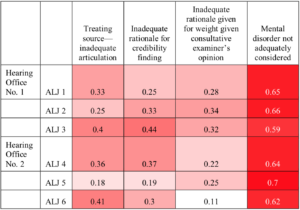

The consistency with which the District of East Dakota finds fault with ALJ decisions from Hearing Office 1 suggests that the problem lies not with a single idiosyncratic ALJ but with some office-wide phenomenon. But the office-wide phenomenon is likely office-specific, because the ALJs from Hearing Office 2 enjoy markedly better success across the board. A bad policy should produce a heat map along the lines of what Table 5 illustrates.

Table 5. Bad Policy