Restructuring Copyright Infringement

Copyright law employs a one-size-fits-all strict liability regime against all unauthorized users of copyrighted works. The current regime takes no account of the blameworthiness of the unauthorized user or of the information costs she faces. Nor does it consider ways in which the rightsholders may have contributed to potential infringements, or ways in which they could have cheaply avoided them. A nonconsensual use of a copyrighted work entitles copyright owners to the full panoply of remedies available under the Copyright Act, including supra-compensatory damage awards, disgorgement of profits, and injunctive relief. This liability regime is unjust, as it largely fails to differentiate among willful infringers, good-faith users who accidently infringe, and ordinary users who fail to understand the intricacies of copyright-protection infringement. No less importantly, one-size-fits-all liability sets back the goals of the copyright system by excessively deterring newly created works and encouraging copyright owners to be less than forthcoming about their expectations from users.

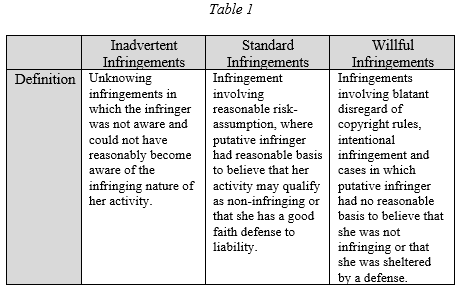

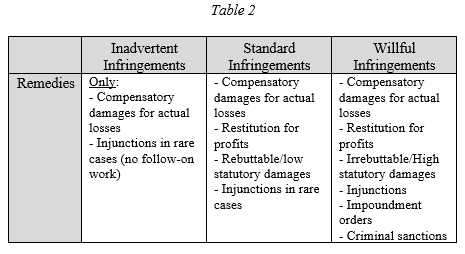

In this Article, we propose a radically different liability regime predicated on the degree of the infringer’s blameworthiness. Concretely, we call for the establishment of three distinct liability categories—inadvertent, standard, and willful infringements—and tailor a specific menu of remedies for each of the categories. Under our proposal, inadvertent infringements would be remedied by compensatory damages only. Standard infringements would entitle copyright owners to a broader variety of monetary damages, including disgorgement of profits and limited statutory damages, but typically no injunctive relief. Willful infringements would be addressed by the full variety of remedies available under the Copyright Act, including punitive statutory damages and injunctions.

We demonstrate that our proposed system of graduated liability yields a far more nuanced and just liability system, one that would also enhance use of existing works and promote future creativity. Limiting the potential liability of users and creators would facilitate the use of copyrighted content and the production of future works. It would also result in a fairer copyright system, the benefits of which would inure to society at large. At the same time, by organizing infringement into our proposed categories, our system would reform infringement law without imposing excessive new fact-finding burdens on courts and litigants.

Introduction

Earlier in 2018, the music world found itself engulfed in yet another copyright controversy, when Universal Music Studios—which owns the copyright in The White Stripes’ “Seven Nation Army”—sent a presuit letter to the creators of the song that won the 2018 Eurovision song contest. According to Universal Music Studios, the winning Eurovision song, “Toy,” performed by the singer Netta, was impermissibly substantially similar to “Seven Nation Army.” Despite the obvious differences in lyrics and melody between the two songs, Universal’s attorneys claimed that they share the same rhythm and harmony.[1]

Such controversies are all too common in the copyright world. In Williams v. Bridgeport Music, Inc.,[2] Robin Thicke acknowledged that Marvin Gaye’s music was an inspiration for the Thicke and Pharrell Williams collaboration “Blurred Lines.”[3] However, while “Blurred Lines” shared some of the “feel” of Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up,” it copied none of the melody or lyrics.[4] The actual sound recording of “Got to Give It Up,” meanwhile, was unprotected due to a copyright technicality,[5] meaning that Thicke and Pharrell could copy Gaye’s recording (but not composition) with impunity. Nevertheless, a jury decided that the appropriation of the mood and feel of Gaye’s song was enough to ground a decision of infringement.[6] From there, it was a short distance to the order of $5.6 million in damages (an amount that was subsequently reduced to about $3.5 million) to the estate of Marvin Gaye, as well as 50% of future proceeds from the song.[7] The appeals and rehearings eventually upheld the result.[8]

These and all too many other cases highlight a central flaw in the extant copyright system of enforcement. Under copyright law’s standard of uniform liability, a defendant who subconsciously or inadvertently borrows protected elements of a copyrighted work is just as liable as one who willfully pirates and distributes an entire work. A trivial infringement—such as a too-long quotation from a book[9] or the unconscious borrowing of elements of a pop tune[10]—is treated just like a willful and malicious pirating and distributing of a copyrighted work.[11] Infringers are liable for damages that bear no proportion to the moral culpability of the defendant or, for that matter, to the damages that their behavior actually causes. The compensation amount in copyright-infringement cases depends only on amounts specified by statute, the harm inflicted on the plaintiff, or the profit of the defendant.[12] Blatant infringers who profit little may end up paying modest damages, while inadvertent infringers who create popular works may end up paying enormous damages.[13] The degree of liability is completely divorced from the degree of culpability of the defendant. It is likewise divorced from the actual harm to society caused by the infringement.

Compare, for instance, the cases of Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. v. Penguin Books USA, Inc.[14] and Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc.[15] Campbell concerned a claim of infringement against 2 Live Crew. The band’s song “Pretty Woman” had copied a bass riff and several lyrics from Roy Orbison’s “Oh, Pretty Woman.”[16] The Supreme Court ruled that the copying was within the bounds of fair use and thus not actionable.[17] A short time later, Alan Katz and Chris Wrinn wrote an account of the O.J. Simpson trial in the style of a Dr. Seuss book, entitled The Cat NOT in the Hat! A Parody by Dr. Juice.[18] Katz and Wrinn clearly thought their copying of the Dr. Seuss style was permissible fair use, as in Campbell.[19] The courts disagreed. Once they determined that The Cat NOT in the Hat! used materials in a style not favored by the fair use doctrine, the courts fell back upon the ordinary doctrines of copyright infringement.[20] The trial court therefore enjoined further distribution of the book.[21] It is extremely difficult to locate copies of the Katz–Wrinn work today.

In this Article, we propose a radical reform in the way copyright law assigns liability. Extant copyright law treats virtually all copyright infringements similarly for purposes of liability.[22] As a general rule, copyright law does not distinguish among different types of infringement. Nor is it open, in its current design, to the idea that liability should be graded based on the degree of wrongdoing by the infringer.[23] Consequently, all infringers are exposed to the full cascade of monetary remedies and injunctive relief.[24] Liability is currently an objective inquiry in which courts decide whether the alleged defendant copied protected expressive elements from the plaintiff.[25] Once the basic elements of an infringement suit—copying and improper appropriation[26]—have been established, liability attaches to the defendant, and the plaintiff is entitled to a menu of potential remedies: statutory damages, recovery of her losses or the defendant’s profits, and, in addition, seizure of infringing copies and even injunctions barring the defendant from using or distributing her own work.[27]

Infringement remedies under current law can be quite harsh, even where the infringement is questionable. The celebrated cases of Bright Tunes Music Corp. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd.[28] (regarding alleged infringement by the George Harrison song “My Sweet Lord”)[29] and Williams v. Bridgeport Music, Inc. (regarding alleged infringement by the Thicke–T.I.–Pharrell song “Blurred Lines”)[30] provide a powerful illustration. In Harrisongs, George Harrison was found to have subconsciously infringed the copyright in The Chiffons’ song “He’s So Fine” by writing and releasing to the public his own hit song “My Sweet Lord.”[31] The court believed Harrison’s testimony about the creative process that yielded “My Sweet Lord,” including the key fact that Harrison composed his song without consciously copying anything from The Chiffons’ earlier song.[32] But little did it help Harrison. The court ordered the payment of $1.6 million of Harrison’s earnings from “My Sweet Lord” to the music publisher of The Chiffons.[33]

As these and many other cases illustrate, copyright law is deliberately draconian. The lines separating infringing “copying” from noninfringing inspiration can be difficult to discern. As well, the boundaries of permitted behavior—under the doctrine of fair use, or as a result of owner-granted or statutory licenses—can be fuzzy.[34] But court decisions are dichotomous. Once the line is crossed and an infringement is established, the rules of relief are uniform and harsh.

There is one outstanding exception to the rule of uniform damages: statutory damages. The statutory provision that provides for statutory damages embodies a three-part design.[35] Section 504(c) differentiates among standard infringements, willful infringements, and innocent infringements.[36] It then gives courts discretion to award damages ranging from $750 to $30,000 per infringement in cases of standard infringements, while empowering them to step up the amount to $150,000 in cases of willful infringements and reduce it to merely $200 in cases of innocent infringements.[37] We posit that the statutory-damages framework constitutes a useful blueprint for reforming infringement analysis in all cases. Yet, we also argue that the other forms of available relief, as well as the structure of statutory damages, should be altered to create a harmonious legal regime.

Our proposed reform, thus, consists of two changes. First, drawing inspiration from the extant rules of statutory damages, we argue that infringements should be divided into three different categories, with varying legal consequences. The first category would be called “inadvertent infringement” and would encompass two prototypical infringement cases: (a) subconscious infringements, as in the case of Bright Tunes Music v. Harrisongs Music;[38] and (b) infringements involving nothing more than appropriation of “concept and feel,” à la Williams v. Bridgeport Music[39] or other cases where the infringement is so small or questionable that a court could conclude that the infringer reasonably believed in good faith that nothing protectable was copied.

At the other end of culpability, the third category would be labelled “willful infringements.” This category would include blatant and inexcusable infringement, such as wholesale, repeated copying of works in their entirety, without plausible claims of license or statutory excuse. The actions of copyright pirates would ordinarily fall within this category.

Finally, a middle, second category would include all other infringements and be labelled “standard infringements.” This category would encompass cases where the defendant is not blameless but is clearly not as culpable as the willful infringer. This would include cases such as colorable cases of fair use in which the defendant mistakenly “went too far,” as happened in Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. v. Penguin Books USA, Inc.[40] and cases in which the infringers accidently exceeded the terms of their licenses. This last type of case is best illustrated by the litigation surrounding claims that the group The Verve infringed upon the copyright in the Rolling Stones’ song “The Last Time” when The Verve sampled too-large a portion of the Andrew Oldham Orchestra’s symphonic recording of the Rolling Stones’ song.[41] According to former Rolling Stones manager Allen Klein, who owned the copyright in the Rolling Stones composition, The Verve had negotiated a license to sample five notes from the Andrew Oldham Orchestra recording, but the portion it actually used slightly exceeded the five-note limit.[42] Rather than face costly and uncertain litigation, The Verve settled out of court and yielded all the revenues from “Bitter Sweet Symphony,” the group’s biggest hit.[43]

The second prong of our reform is to tailor the remedies for each of our proposed three categories to the degree of infringer culpability. Under our proposal, for cases of inadvertent infringements, courts would be limited to awarding purely compensatory damages and, in very rare cases, also injunctive relief to stop unauthorized distribution of unauthorized copies. For cases of standard infringements, courts would be able to expand the remedial menu and, in addition to compensatory damages, order disgorgement of profits or, in the alternative, limited statutory damages. Here, too, injunctive relief would typically be withheld. Finally, in cases of willful infringement, courts would be able to utilize the full panoply of copyright remedies, including all of the above, as well as high statutory damages, criminal sanctions, and injunctive relief. Importantly, the new liability regime would limit courts both in lawsuits for standard remedies and for statutory damages, thus bringing uniformity to copyright remedies while differentiating liability according to culpability.

Proper allocation of the burdens of proof would be necessary for our reform to be workable. In our scheme, all infringements would be presumptively standard, unless either the defendant could prove her innocence or the plaintiff could prove willfulness or malice. In other words, the burden of proving that a case should be classified as an inadvertent infringement case would rest with the user–infringer, while the burden of proof that an infringement was willful would lie with the plaintiff copyright owner. Yet, we would supplement the aforementioned rules concerning the burden of proof with one additional possibility: we would allow users to initiate suits seeking declaratory judgments that they were entitled to the status of an innocent infringer.

Calibrating liability (and remedies) to culpability holds obvious intuitive moral appeal. But it is also advantageous from a utilitarian perspective. Copyright protection imposes substantial information costs on third parties, among them, other authors. The high level of risk of legal liability when creating new works is the result of many factors in combination: the vast universe of protected works, the difficulty of distinguishing between elements that are copyrighted (that cannot be used without permission) and uncopyrighted (that can be freely used), the broad scope of liability that makes even unconscious copying actionable, and the existence of malleable defenses to liability. The problem is exacerbated by the absence of a readily available registry of all existing works. This makes it nearly impossible to know not only what works and which aspects of them are protected but also who the relevant rightsholders are. In this informationally treacherous environment, the best way to curb the risks faced by aspiring authors is to limit the liability to which they will be exposed if they unknowingly commit a copyright infringement. This not only reduces unnecessary barriers to entry by new authors, it also incentivizes authors to make their claims known as widely as possible, so as to foreclose the possibility of innocent infringements.

Efficiency supports bringing copyright punishments closer to existing moral intuitions for another reason as well. Extant literature points to a significant gap between popular understandings of social norms of copyright and the law of copyright, as well as between the demands of the law and popular understanding of those demands.[44] These gaps increase the costs of enforcing copyright. Potential defendants will not conform their behavior to a law of which they are unaware, and given both the difficulty of detecting infringement and the difficulty of understanding the law, it may be rational to remain ignorant. At the same time, these gaps may lead judges and courts to depart unilaterally from the legal norms when they believe the law is unnecessarily harsh. By reducing these gaps, lawmakers can help copyright enforcement become cheaper and more uniform. Even if penalties are reduced in some cases, improvements in the rate and accuracy of enforcement can lead to a better incentive structure of the law.[45]

Concerns for efficiency also lay behind the scope of our potential reform. Given the wide variety of potential types of infringements, one might imagine an infinite range of remedies, each tailored to the precise degree of culpability. However, administering such infinitely tailored remedies would prove enormously costly for two reasons: learning and administering a new (and unbounded) legal system would place a heavy burden on courts and litigants, as would gathering and exposing evidence relevant to the infinitely tailored system.[46] By building on the existing categories of statutory damages, and by limiting the potential classes of liability to three, we minimize the potential administrative and litigation costs associated with our proposed overhaul of the law of liability. In particular, given the fact that most copyright-infringement cases already involve claims for statutory damages,[47] our proposal will not add substantially to the existing evidentiary burden.

We lay out our argument in three parts. In Part I, we review the extant law of infringements, demonstrating the vast array of circumstances and harms encompassed by the term “copyright infringement.” In Part II, we examine the remedies available under copyright law, while emphasizing, in particular, their Procrustean nature. Additionally, we demonstrate why the narrow range of available remedies is socially undesirable. In Part III, we offer our proposed reform of copyright remedies. Finally, in Part IV, we explain why, despite the advantage of staggered remedies, we offer only three categories based on culpability.

I. The Wide World of Infringements

In this Part, we highlight just some of the many ways in which copyright law might be infringed. The categories of infringement we offer here are not those of the law. In fact, the law conceives of all infringements as identical. As we will show in the next Part, no matter what kind of infringement, copyright law offers the same remedy.

We begin with some general observations about infringements, before offering a tentative classification of different kinds of infringements based on culpability. As we show in the conclusion of this Part, mistakes are the source of many—and probably most—infringements.

A. The Vagueness of Infringement Law

As a preliminary matter, it is important to observe that the variability of infringements is deeply rooted in copyright law. Copyright law is, of necessity, vague and often maddeningly so. Copyright law grants authors[48] monopoly rights in their expressions, but defining the nature or even the protected expressions of that monopoly is no easy matter. Perhaps the most famous expression of this vagueness is Justice Story’s observation that “copyrights approach, nearer than any other class of cases . . . to what may be called the metaphysics of the law, where the distinctions are, or at least may be, very subtle and refined, and, sometimes, almost evanescent.”[49] No less famous is Judge Learned Hand’s explanation of copyright law’s idea–expression dichotomy:

The test for infringement of a copyright is of necessity vague. In the case of verbal “works” it is well settled that although the “proprietor’s” monopoly extends beyond an exact reproduction of the words, there can be no copyright in the “ideas” disclosed but only in their “expression.” Obviously, no principle can be stated as to when an imitator has gone beyond copying the “idea,” and has borrowed its “expression.” Decisions must therefore inevitably be ad hoc.[50]

Copyright law protects all original works of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression for more than a fleeting moment.[51] Works do not need to be published to be protected.[52] While there is a copyright registry, works need not be marked or registered to qualify for protection.[53] It is difficult to know what qualifies as a work of authorship; in recent decades, protection has been claimed for works as diverse as computer operating systems,[54] tattoos,[55] and a wildflower garden.[56]

The uncertain legal standards combine with the law’s formalities to create yet more doubt. For instance, while copyright protection is extremely long-lasting (generally lasting for more than a century),[57] the terms of protection have changed over time, along with the formal requirements for protection,[58] and even the definitions of protected elements of a work.[59] Thus, it is that as recently as 2013, the courts found themselves ruling on an ownership dispute over the copyright in different elements of the Superman character,[60] who first appeared in comic books in 1938.[61] In some cases, courts have split up the rights in works in ways that would strike a layperson as bizarre, such as by distinguishing ownership of a character’s catchphrases from the character’s characteristic wardrobe.[62] The result is that users of expressive works can never be sure which works are under legal protection and which have fallen into the public domain and at what point the legal protection, if it exists, expires. The informational haze shrouding the copyright terrain has even spawned the odd legal phenomenon of “orphan works”—works that are subject to copyright protection but whose rightsholders are unknown.[63]

Together, legal vagueness, unclear information in rights, and a number of market practices combine to create an atmosphere in which copyright rights can be infringed in numerous ways that are not willful and perhaps not even readily detectable.

It is against this background that we turn to a description of several different kinds of infringement, with a focus on the ways rights may be infringed without willfulness. We will argue infra that these several kinds of infringements can be roughly grouped into three categories—willful infringements, inadvertent infringements, and “standard” infringements.[64]

B. The Different Types of Infringements

1. Willful and Blatant Infringements.—We begin with the infringements that the law must combat most strongly: willful and blatant infringements of copyrights. Notwithstanding all the ambiguity surrounding copyright law, there are many cases that are easy. Counterfeit DVDs, for instance, are produced wholesale by pirates who know that they are copying a copyrighted work (a motion picture) and then distributing it to the public without any authorization.[65] The counterfeiters are not confused about the illegality of their actions. They are simply relying on not getting caught.

Every year there are numerous enforcement actions against such willful and blatant infringements.[66] Consider the enforcement action that was brought against Danny Ferrer.[67] Ferrer, together with others, operated the piracy website www.buyusa.com, where he sold illicit copies of copyrighted software products, such as Adobe and Autodesk (among others).[68] Ferrer’s infringing activities lasted several years, causing the rightsholders harm that totaled nearly $20 million.[69] Ultimately, Ferrer was sentenced to a prison term of six years and was ordered to pay $4.1 million in restitution.[70] In addition, he was forced to forfeit a whole variety of luxury goods he had acquired from the proceeds of his illegal activities.[71]

Although Ferrer’s case is extreme in terms of the punishment meted out to him, it is highly representative of infringing activities concerning copyrighted software, movies, and music files on the Internet. Infringements of copyrights in such works often consist of a knowing and willful mass production of illegal copies of protected works, and, thereafter, the knowing and willful offering of those copies to the public at a heavily discounted price.

As we explicate further in Part III, we classify these kinds of infringements “willful infringements.”[72]

2. Unknowing Infringements.—At the other end of the spectrum are inadvertent infringements: instances where the infringement is due to a reasonable and good-faith interpretation of the law and facts that leads the infringer to believe she is doing nothing wrong. As we will see, there are many different instances where someone may use a copyrighted work in a forbidden manner, yet lack culpability. Roughly speaking, the innocence of the infringer may stem from two different kinds of mistakes. The infringer may make a mistake of law, or incorrect predictions about the way courts are likely to interpret the law that lead her to believe that the law permits her activity. Alternatively, the infringer may make a mistake of fact or believe certain things about the quality of a work or the available licenses that lead her to believe that her activity is not infringing.

The most extreme type of inadvertent infringement is one where even after committing an act that the court will eventually find to have been infringing, the infringer is unlikely to know that she did anything wrong.

In theory, such unknowing infringements should not be possible. Although the Copyright Act does not explicitly require it, case law is quite clear in demanding that any case of infringement be supported by a finding of “copying in fact.”[73] That is, according to the courts, an infringement does not take place unless “the defendant, in creating its own rival work, used the plaintiff’s material as a model, template, or even inspiration.”[74] Yet, despite this clear element of the case law, courts have signaled their willingness to find an infringement where the defendant was not aware of the plaintiff’s work, and did not consciously use it even as inspiration.

The extreme example of this kind of infringement is provided by the famous case of Bright Tunes Music v. Harrisongs. Bright Tunes involved a suit brought against George Harrison, the former Beatle, alleging that his hit song “My Sweet Lord” infringed Bright Tunes’ copyright in The Chiffons’ “He’s So Fine.”[75] In response to the suit, Harrison attested that he did not copy The Chiffons’ song or borrow from it.[76] The court explained that while it believed Harrison, he had nevertheless infringed Bright Tunes’ copyright:

Seeking the wellsprings of musical composition—why a composer chooses the succession of notes and the harmonies he does—whether it be George Harrison or Richard Wagner—is a fascinating inquiry. It is apparent from the extensive colloquy between the court and Harrison covering forty pages in the transcript that . . . Harrison [was not] conscious of the fact that [he was] utilizing the He’s So Fine theme. . . .

What happened? I conclude that the composer, in seeking musical materials to clothe his thoughts, was working with various possibilities. As he tried this possibility and that, there came to the surface of his mind a particular combination that pleased him as being one he felt would be appealing to a prospective listener; in other words, that this combination of sounds would work. Why? Because his subconscious knew it already had worked in a song his conscious mind did not remember. . . . Did Harrison deliberately use the music of He’s So Fine? I do not believe he did so deliberately.[77]

The court reasoned that Harrison was probably exposed to The Chiffons’ song that was released in 1963 and was subconsciously influenced by it when he wrote his song that was released to the public in November of 1970. That Harrison was unaware of this fact was of no help to him.[78]

Subconscious copying also played a key role in the case of Three Boys Music Corp. v. Bolton.[79] This case proceeded on a claim that Michael Bolton’s song entitled “Love is a Wonderful Thing” plagiarized a song with the same title by the Isley Brothers.[80] Naturally, the identical title of the two songs could (and did) raise suspicion of illicit behavior, but it turns out that 129 songs bearing the same title were registered at the time of the suit.[81] That Bolton’s song was released more than 30 years after the original did not save him.[82] Nor did it help that the Isley Brothers’ song did not attain meaningful commercial success.[83] In fact, the court used Bolton’s admission of his admiration of the Isley Brothers to corroborate the jury’s finding that Bolton copied the Isley Brothers’ song.[84]

To be sure, the court did not rule that Bolton had infringed the Isley Brothers’ copyright; it only upheld a jury finding that Bolton had infringed. Nonetheless, it is difficult to read the court’s opinion and remain unimpressed with how a borderline case of plausible “copying” can suffice to uphold a ruling of infringement. According to the Court:

The appellants contend that the Isley Brothers’ theory of access amounts to a “twenty-five-years-after-the-fact-subconscious copying claim.” Indeed, this is a more attenuated case of reasonable access and subconscious copying than [Bright Tunes Music]. In this case, the appellants never admitted hearing the Isley Brothers’ “Love is a Wonderful Thing.” That song never topped the Billboard charts or even made the top 100 for a single week. The song was not released on an album or compact disc until 1991, a year after Bolton and Goldmark wrote their song. Nor did the Isley Brothers ever claim that Bolton’s and Goldmark’s song is so “strikingly similar” to the Isley Brothers’ that proof of access is presumed and need not be proven. . . .

. . . .

Teenagers are generally avid music listeners. It is entirely plausible that two Connecticut teenagers obsessed with rhythm and blues music could remember an Isley Brothers’ song that was played on the radio and television for a few weeks, and subconsciously copy it twenty years later.[85]

Needless to say, there is a vast gulf between blatant pirating of copyrighted works and subconscious copying of the same.

As we explicate further in Part III, we classify these kinds of infringements as “inadvertent infringements.”[86]

3. Infringements Related to Questions About the Work’s Protection.—Infringements vary not only due to the behavior of the infringer. They also vary due to the nature of the copyrighted work. Sometimes, the application of copyright law to a particular work is obvious. Copyright law, for instance, clearly protects the text of a novel.[87] But the law’s protection does not end there. The novel’s characters[88] and style[89] may be protected, as may other “nonliteral” aspects of the work. Indeed, every protected work contains both protected and unprotected parts. The text of a history book is protected but not its historical facts.[90] The plot of a movie is protected but not insofar as the plot is unoriginal or consists of scènes à faire.[91] Someone may copy elements of a work she thought were unprotected, and find out later to her chagrin that the court considers her copying an infringement.

In some cases, the statute explicitly divides the work into protected and unprotected parts. For example, the copyright in architectural works is limited to “overall form as well as the arrangement and composition of spaces and elements in the design [of a building], but . . . not . . . individual standard features.”[92] A more controversial example is provided by the law of copyright protection of works of industrial design—“pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works” that are “useful articles” in the jargon of the Copyright Act.[93] Such works are protected only in their “form” but not their “mechanical or utilitarian aspects,” and only to the degree that their design “incorporates pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features that can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.”[94] An espresso machine may thus enjoy copyright protection for part of the way it looks: for its form, but not its mechanical aspects, and even then, only to the degree that the artistic aspects of the form are identified separately from the utilitarian aspects. Years of litigation about such items as belt buckles,[95] bicycle racks,[96] streetlamps,[97] mannequin heads,[98] and cheerleading uniforms[99] have failed to draw a clear line.[100]

An additional complication is created by the fact that copyrights are time limited, but the protected aspects of works are not created instantaneously at a single moment. Consider the litigation surrounding the copyrighted character Sherlock Holmes. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a writer in the late nineteenth and early-twentieth century whose most famous works concerned the adventures of the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes. The first Sherlock Holmes story appeared in 1887 and the last in 1927.[101] It is evident that the majority of the Sherlock Holmes stories have long been in the public domain. However, the Doyle estate has successfully upheld the copyright in ten short stories published from 1923 and onward.[102] The result is that any marginal accretions to the Sherlock Holmes character that appear in those final short stories are still under copyright protection. Warner Brothers could lawfully use Sherlock Holmes as the central character in its 2009[103] and 2011[104] films, without a license from the Doyle estate, so long as it avoided any references to Holmes’s development in a character in the final ten short stories. Likewise, a different studio could today make its own original Sherlock Holmes films, as long as it avoided using the last ten short stories, or any aspects of the character that were original to the Warner Brothers’ films (or other still-protected depictions in films and television programs). In other words, when considering the Sherlock Holmes character, like any other copyrighted work created over time, one must view the work as layered; although the work may seem a seamless whole, in fact it is comprised of different pieces built upon one another, some of which enjoy copyright protection, and others of which do not.

Figuring out whether one has copied a protected part of a work is a perennial difficulty in the law of copyright. As Judge Learned Hand famously observed in the 1930 case Nichols v. Universal Pictures Corp.,[105] “[n]obody has ever been able to fix that boundary [between protected elements and unprotected “abstractions”], and nobody ever can.”[106] Indeed, in Nichols, which concerned the claim that the plot of the play The Cohens and the Kellys infringed upon the plot of the earlier play Abie’s Irish Rose, Judge Hand was forced to recite the plots of both plays at length, before dismissing the case with such imprecise observations as:

[W]e think both as to incident and character, the defendant took no more—assuming that it took anything at all—than the law allowed. The stories are quite different[:]

. . . [T]he theme was too generalized an abstraction from what she wrote . . . .

. . . [And] as to her characters[, they are mere] . . . stock figures.[107]

The difficulty in applying the law is perhaps best illustrated by comparing two cases involving stories about the continuing adventures of well-known characters. The first, Warner Bros. Pictures Inc. v. Columbia Broadcasting System,[108] involved the fictional detective Sam Spade and other more minor fictional characters who appeared in the Sam Spade adventure The Maltese Falcon.[109] Sam Spade was the main character in Dashiell Hammett’s novel The Maltese Falcon, published in serial form from 1929–1930.[110] Later in 1930, Hammett (and his publisher Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.) sold all television, radio, and movie rights to Warner Brothers; Warner Brothers adapted the novel into several different film versions, of which the most successful by far was the 1941 film The Maltese Falcon, which starred Humphrey Bogart.[111] The controversy developed in 1946, when Hammett granted the Columbia Broadcasting System the right to use the character Sam Spade (and several other characters) in a radio drama entitled “Adventures of Sam Spade” that was later broadcast weekly in half-hour episodes until 1950.[112] Warner Brothers sued, claiming that the radio shows infringed upon the rights in the character Sam Spade it had acquired when it purchased the radio rights to The Maltese Falcon.[113] However, the district court and then the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Hammett and Columbia Broadcasting System on the grounds that the character Sam Spade was not a copyrighted work included in The Maltese Falcon; indeed, according to the court, the character Sam Spade could not be copyrighted at all since he was merely the “vehicle[] for the story told, and the vehicle[] did not go with the sale of the story.”[114]

Nearly the opposite approach was exhibited by a district court in California in Anderson v. Stallone[115]—litigation concerning the character Rocky Balboa, and other, more minor, fictional characters that appeared in the Rocky film series.[116] Timothy Anderson, a fan of the Rocky film series, was inspired by Sylvester Stallone’s brief comments during a promotional tour of Rocky III regarding the potential plot of Rocky IV.[117] Building on Stallone’s vague idea of a fight in Moscow between Rocky Balboa and a Soviet fighter, Anderson wrote a 31-page summary of the plot of a film (a “treatment,” in the jargon of the film industry) involving a fight between Rocky and a highly trained Soviet fighter, which he then delivered to studio executives.[118] According to Anderson, Stallone’s final script for Rocky IV copied the plot of Anderson’s treatment.[119] The court ruled for Stallone.[120] While purporting to apply the same standard as the Warner Brothers decisions,[121] the court ruled that “the Rocky characters were so highly developed and central to the three movies made before Anderson’s treatment that they ‘constituted the story being told’” and were, therefore, “[e]ntitled [t]o [c]opyright [p]rotection [a]s [a] [m]atter [o]f [l]aw.”[122] Consequently, ruled the court, Anderson could not enjoy copyright protection for any of his treatment; Anderson’s treatment was nothing more than an unauthorized derivative work which unlawfully used Stallone’s copyrighted characters.[123] It was Anderson, rather than Stallone, who had infringed.

Against this background of legal uncertainty, one might easily infringe, yet fail to identify the legal consequences until the court’s ruling. Does a television commercial infringe the copyrights in the James Bond films when it shows a tuxedoed American male spy engaged in flirtatious banter with an attractive female companion while driving a Honda del Sol to escape a villain in a helicopter, all to the sounds of “loud, exciting horn music”?[124] The district court in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer v. American Honda Motor Co. found the question sufficiently vexing that it rejected Honda’s motion for summary judgment and left the question of infringement to the jury.[125] Certainly, it is possible to rule that Honda infringed upon the copyright in the James Bond character as depicted in the films owned by MGM (though not non-MGM films and not the Ian Fleming novels about James Bond). However, it is also possible to conceive of a court ruling that Honda did not copy anything protected by copyright.

Perhaps the most controversial nonliteral infringements are those that infringe the “look and feel” of the copyrighted work. A “look and feel” infringement, unlike an infringement of nonliteral aspects like the plot of a film, is the most ethereal type of infringement. In cases that find the defendant to have infringed upon the “look and feel” or “concept and feel” of a copyrighted work, the courts suffice with the decision that the infringing work “feels” excessively like the original.[126] Consider, for instance, the case of Roth Greeting Cards v. United Card Co.[127] The case involved two companies that produced greeting cards with simple illustrations and banal greeting card sentiments. Roth complained that United had copied seven greeting cards.[128] The court originally expressed some doubt that Roth’s cards were sufficiently original to warrant copyright—the cards were, after all, greeting cards expressing greeting card sentiments—but the court ultimately ruled that the cards were protected by copyright.[129] When it came to the question of infringement, Roth could not point to anything specific that had been copied, but the court nevertheless reversed a judgment in favor of United and found that United had violated Roth’s copyright by copying the “total concept and feel” of Roth’s cards.[130] The court thought that the combinations of simple pictures and trite messages in United’s cards were so similar to the combinations of simple pictures and trite messages in Roth’s cards that an “ordinary observer” would view the Roth cards as having been impermissibly copied.[131]

Perhaps the most famous “concept and feel” case is Sid & Marty Krofft Television Productions, Inc. v. McDonald’s Corp.,[132] which considered whether McDonald’s had infringed the Kroffts’ copyright in their H.R. Pufnstuf television series when the fast food company produced a series of commercials showing the fantasy “McDonaldland.”[133] While acknowledging that the McDonald’s commercials did not literally copy anything in the H.R. Pufnstuf series, and that they did not copy nonliteral elements such as plot or characters, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals nevertheless upheld a ruling in favor of the Kroffts due to the McDonald’s commercial’s similarity to the “total concept and feel” of the H.R. Pufnstuf series.[134] According to the court, it was essential that the target audience was children because this meant the court had to consider “the impact of the respective works upon the minds and imaginations of young people.”[135] The court then determined that notwithstanding the “subjective and unpredictable nature of children’s responses,”[136] an audience of children would necessarily view the commercials as having copied the “total concept and feel” of H.R. Pufnstuf.[137]

Elements of the maddening vagueness of “total concept and feel” cases threaten to leak into other infringement cases due to the standards used by courts to determine impermissible similarity. Consider, for instance, the standard developed by Judge Learned Hand in the 1960 case Peter Pan Fabrics, Inc. v. Martin Weiner Corp.[138] and used ever since in the Second Circuit. Hand explained that the way to determine whether a fabric pattern had infringed on the copyrighted pattern of a different fabric was by asking whether “the ordinary observer . . . would be disposed to overlook [the disparities], and regard [the patterns’] aesthetic appeal as the same.”[139]

Clearly, classifying infringements of nonliteral elements of copyrighted works is not an easy task. Certainly, infringements of this sort are not as culpable as willful and knowing piracy. Yet, often, one cannot view the infringements as inadvertent or innocent. As we explicate further in Part III, we include most of these kinds of infringements within a category we call “standard infringements.”[140] However, in light of the vagueness of the doctrine, there may be extreme cases where the infringement involves nothing more than adoption of the “look and feel” of the copyrighted work. In those cases, we suggest that the infringer should be seen as no more culpable than an inadvertent infringer.

4. Infringements Related to Questions About the Scope of Legal Protection.—Uncertainty in the law lies at the heart of other types of infringements as well. Some infringements are distinguished by questions about the scope of the law’s protection rather than the scope of the work. It is clear, for example, that the actual text of a novel is part of the copyrighted work protected by the law, even if there may be disputes about the parts of the plot that are protected. Nonetheless, not every use of the text constitutes infringement. The fair use doctrine, for instance, gives critics the rights to quote a small portion of the text in a book review without a license from the author.[141] Unfortunately, as with so many other aspects of copyright law, limitations on the scope of copyright are far from obvious, and users of copyrighted works frequently make mistakes.

Consider the extreme case of “appropriation art.” Appropriation art consists of artistic works that use preexisting works with little or no transformation;[142] in the terminology of the Tate Gallery, appropriation art is “the more or less direct taking over . . . [of] a real object or even an existing work of art” “into a [new] work of art.”[143] Appropriation artist Sherrie Levine, for instance, photographs the preexisting photographs of other photographers.[144] Her work After Walker Evans, created and displayed in 1981, consisted of Levine’s photographs of a set of famous Walker Evans photographs of poor rural Americans during the Great Depression.[145] The Evans estate naturally accused Levine of copyright infringement, though the matter was ultimately settled without litigation.[146]

Appropriation artists have often claimed that their works do not infringe on the grounds that the works are “fair uses” of the original. The courts have sometimes accepted and sometimes rejected such claims. Jeff Koons has been repeatedly sued for copyright infringement, and while his fair use claims prevailed in Blanch v. Koons,[147] they failed in Rogers v. Koons,[148] United Feature Syndicate v. Koons,[149] and Campbell v. Koons.[150] The most striking recent ruling on appropriation art was issued by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in the case of Cariou v. Prince.[151] Richard Prince, the defendant, was an appropriation artist who copied thirty of Cariou’s photographs of Jamaicans and transformed them into Prince’s style “by among other things painting ‘lozenges’ over their subjects’ facial features and using only portions of some of the images.”[152] As one might expect of an appropriation artist, Prince denied any intent for his works to be transformative, saying that “he ‘do[es]n’t really have a message,’ that he was not ‘trying to create anything with a new meaning or a new message.’”[153] Nonetheless, the court found fair use with respect to twenty-five of Cariou’s images used by Prince,[154] while “express[ing] no view as to” Prince’s claim of fair use for the other five images.[155]

Fair use claims are not limited to appropriation art, of course. Fair use claims have been made regarding multimillion dollar parody films,[156] exact copying of software in order to reverse engineer it,[157] advertising campaigns,[158] the compilation of photocopied materials for instructional courses,[159] the copying of television broadcast for later viewing at home,[160] the recording of pieces of music in order to listen to them on different devices,[161] the mass digitization of books,[162] systematic miniaturization and transmission of digital images,[163] the photocopying and archiving of academic articles for future research,[164] the display of a copyrighted image in the background of a television show set for a total of twenty-seven seconds,[165] and the quotation of fewer than approximately 300 words from a 2,000-word book in a news story.[166] Of course, only some of these fair use claims have been successful, but for those unfamiliar with the line of case law, the outcomes are difficult to predict: who would guess, for example, that copying the entire text of five million books would be found fair use,[167] while the quotation of a mere 300–400 words from a 2,000-word book would not?[168]

Fair use is not the only legal tool that may grant users the ability to copy protected works in a manner that would otherwise be seen as infringing. The Copyright Act is replete with mandatory licenses and exceptions granting users the rights to use works in such diverse situations as face-to-face classroom instruction,[169] advertising,[170] and background music in retail outlets.[171] Some of the statutory licenses are straightforward, but many others are hideously complex and have led to repeated litigation over such apparently trivial questions as the square footage of the retail space in which the musical work was being played.[172]

The uncertain boundaries of the many statutory licenses, and especially that of the notoriously vague fair use provision, lie at the heart of many infringement cases. Many users of copyrighted works reasonably believe that their use is permitted by the statutory exceptions to copyright protection. And, indeed, often the courts vindicate these beliefs with a finding of fair use or other statutory privilege.

The culpability of the user in cases where the user improperly relies on statutory exceptions is mixed. On the one hand, the user often knows that the acts she is committing are prima facie within the monopoly rights of the copyright owner, or, at the very least, that they skate very close to the owner’s rights. Google, for instance, clearly knew that when it scanned millions of books for its Google Books project, it was copying many copyrighted works without permission from the copyright owners.[173] Likewise, Aereo, in copying over-the-air transmissions of copyrighted programs and then streaming them to customers, knew that its activities could be characterized as forbidden copying and public performance.[174] Yet, while the users know they are potentially infringing, they also have good reason to believe they are not violating the law. Google had a more than plausible claim that its activity was within the ambit of fair use, while Aereo had a strong argument that its copying was permitted by fair use and its transmissions were not “public” or “volitional.” As it happened, Google’s gamble was successful: its claim of fair use was vindicated first by the trial court[175] and then by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals.[176] Aereo’s gamble, on the other hand, was not. After Aereo prevailed in the First and Second Circuit Courts of Appeals, the Supreme Court ultimately ruled that Aereo’s model was too similar to that of cable television and therefore a forbidden public performance.[177]

In short, the culpability of infringers is best seen as somewhere between the innocence of “subconscious” infringers and the willfulness of pirates. As we explicate further in Part III, we classify most of these kinds of infringements as “standard infringements.”[178]

5. Infringements Related to Questions About the Identity of the Owner.—One of the most unusual sources of infringements is user confusion regarding the ownership of a copyrighted work. Even where one is certain that a work is subject to copyright, and likely still within the protection of the copyright law––as with a piece of music that is clearly of recent origin––one may still not know to whom the rights belong.

Modern changes in copyright law are partly to blame for this situation. Prior to 1978, copyright law required notice of copyright ownership to accompany general distributions of copies of the work to the public, which meant that often one could discover the initial owner of copyright in a work by examining a copy.[179] However, even in the era before 1978, knowledge of copyright ownership was limited. For instance, copyright ownership could be transferred after distribution of the work, but the copies would not reflect this fact. In any event, changes in the law in recent decades have exacerbated, rather than ameliorated, the problem. After January 1, 1978 (the effective date of the Copyright Act of 1976), and especially after the Berne Convention Implementation Act of 1988, the notice requirement was gradually eliminated.[180] Today, there is no notice requirement at all, meaning that a copy of a protected work can bear no indication whatsoever of the identity of the copyright owner, or even the fact that the work is protected by copyright law, yet still enjoy the full protection of copyright law.[181] Additionally, while there are circumstances in which the owner must register copyright ownership, failure to do so is never fatal. A search through the copyright registry may thus provide no indication of ownership, even though the work is protected.

The difficulty of identifying ownership of copyrighted works has become known as the “orphan works” problem. A 2015 report of the Copyright Office defined orphan works based on its 2006 report as “original work[s] of authorship for which a good faith prospective user cannot readily identify and/or locate the copyright owner(s) in a situation where permission from the copyright owner(s) is necessary as a matter of law.”[182] While the Copyright Office described the scope of the problem as “elusive,” it acknowledged that the “orphan works problem is real.”[183] The orphan works problem occurs when potential users have encountered a work of authorship of which they wish to make use but cannot figure out to whom it belongs. The situation may arise because no identifying information appears in the copy of the work examined by the potential user or because the information is out of date (due to transfers, etc.). While in some cases the potential user will throw up her hands and avoid using the work, in others, she will take a chance and use the work, risking a future infringement suit.

Much speculation surrounds the topic of orphan works. According to one published estimate, up to 90% of all works currently protected by copyright law are “orphaned.”[184] As technology changes, and the number of digital copies of copyrighted works moves into the trillions,[185] the number of copies without sufficient identifying information will doubtless grow.

Given the hype surrounding the problem of orphan works,[186] it may be surprising to learn that the problem is even worse than usually described. The reason for this is the layered nature of copyrighted works. Almost inevitably, every copyrighted work contains within itself other copyrighted works. A novel, for instance, contains a plot and characters, which can be separately copyrighted and protected. This means that even if a novel is sufficiently well identified to allow potential users to obtain licenses from the owner of the novel as a whole, it will not be entirely clear who owns the component pieces of the novel that the user wishes to license. Thus, for instance, if Alice wishes to utilize a portion of a film whose copyright owner is known to her, she will still have to worry about the question of whether the film incorporates plot elements or characters from a work owned by someone else.[187]

Beyond these basic problems in identifying owners, several copyright doctrines—and in particular, the termination right—further exacerbate the problem of tracing ownership. The 1976 Copyright Act granted authors who transfer their copyright (and, in limited cases, other copyright owners)[188] the right to cancel the transfer several decades later and reclaim ownership in the work.[189] The 1976 Act’s termination right applies retrospectively as well as prospectively[190]: transfers that took place before the effective date of the 1976 Act can be terminated as well. Additionally, while the 1976 Act’s termination right was new, even under older copyright law, there were instances in which a transferee might lose ownership of a copyright that had been lawfully purchased. Under the 1909 Act, for instance, copyright terms were compound; that is to say, creators of a copyrighted work would get two distinct terms of protection—an initial 28-year term and an additional 28-year term if the renewal paperwork was properly filed.[191] A peculiarity of case law under the 1909 Act provided that a creator could sell all her rights in a copyrighted work (for the full 56 years), but if she died before the onset of the renewal term, the transfer of the second 28-year term would fail, and ownership would revert to the heirs of the original owner.[192] In other words, under the old law, as well as the new, even where someone “owns” all of a copyright, there might still be someone else lurking about who has a residual right to take it away.

As a result of all these factors, copyright “clearance” is extremely difficult and sometimes impossible. Despite the best efforts of a user, it may not be possible to figure out from whom to license a work.

In general, there is a large category of cases in which users wish to use works without having any clear idea of the identity of the owner or how to go about getting permission. If the frustrated user takes the chance of using the work without a proper license, she is clearly not an inadvertent infringer. However, just as clearly, it does not make sense to treat her as culpable to the same degree as a willful infringer. We suggest that these cases belong under the category of “standard infringements.”

6. Infringements Related to Questions About the Scope of a License.—It might seem odd to suggest that the scope of licenses can constitute a fertile source of mistaken infringements. One might suspect that the licensing of copyrighted works is the quintessential sign that no infringement has taken place, or that if a work has been infringed, it is due to malice. After all, if the right to the copyrighted work has been licensed, it would seem necessary for the user and the owner to have reached some meeting of the minds as to how the copyrighted work will be used. Yet, in practice, it turns out that even where users hold a license, infringements due to mistakes about the scope of licenses are legion.

Mistakes about the scope of licenses are more frequent than one might expect. For example, in 2014, Getty Images released 35 million copyrighted images from its catalog to the Internet, making them available, free of charge, for noncommercial use.[193] In exchange, Getty required users to embed the images with Getty’s software embedding tool in order to ensure that proper credit is given and to monitor users and show them ads.[194] Users, however, are often unaware of the existence of limitations and restrictions on the use of content or simply miscomprehend them. Furthermore, they are sometimes implicated in infringement activities by trusted third parties, such as web designers.[195]

A recent empirical study by Hong Luo and Julie Holland Mortimer of infringements involving digital images reveals that “infringement of digital images is often unintentional. Unintentional infringement may arise either through misinformation about licensing obligations, or because third parties infringe on behalf of a user (e.g., a web designer includes an image on a firm’s website).”[196]

Specifically, Luo and Mortimer report that 85% of infringers claimed that they were unaware of the infringement or that it arose as a consequence of the actions of hired third parties.[197] The percentage among small firms was even higher and reached 88%.[198] Interestingly, they also note that the price requested by copyright owners for the use of the content, i.e., the license fee, had no effect on the level of infringement.[199]

The ambiguity of licenses is compounded by the long-lasting nature of copyrights. In the course of the century and more that copyrights can last, technology can change, rendering the meaning of earlier copyright agreements uncertain. Does a distribution license for a film include the possibility of distribution by video cassette or streaming by internet?[200] Do publication rights for a book include the right to publish it electronically?[201] Such questions have proved a fertile source of litigation.

A further degree of confusion is added by the case law permitting unwritten implied licenses. The Copyright Act requires an attestation in writing for all “transfer[s]” of copyright rights,[202] but the writing requirement does not apply to the granting of nonexclusive licenses.[203] In such cases, the behavior of the parties may create a license whose terms are unknown and unknowable. Consider, for example, the case of Effects Associates, Inc. v. Cohen.[204] Cohen, “a low-budget horror movie mogul,” asked Effects Associates, a special effects studio, to produce special effects footage for the movie The Stuff.[205] While the studio produced the footage as promised, and Cohen used the footage in the movie, Cohen refused to pay the agreed-upon consideration.[206] According to the Copyright Act, transfers of copyright ownership require a written agreement.[207] Cohen had obtained no such written agreement.[208] Effects Associates sued for copyright infringement and fraud.[209] In a surprising decision, Judge Kozinski ruled that there was no copyright infringement since Cohen had an implied nonexclusive license to use the disputed footage in his movie.[210] While Effects Associates still had the right to payment according to the contract, it could not object to the use of its copyrighted footage.

Not only may licenses be created by behavior; they may also be rescinded by the same. An interesting illustration is provided by the recent case of Garcia v. Google Inc.,[211] in which an actress named Cindy Lee Garcia sought to enjoin the distribution on YouTube of the controversial film Innocence of Muslims on the grounds that she owned a copyright in her acting performance in the relatively small part in which she appeared in the film.[212] Garcia had signed a contract before acting in the film, but the contract had not explicitly resolved the issue of copyright in Garcia’s performance and she argued that any license she might have granted was invalid, as it had been obtained by fraud (she had been misled about the nature of the film and the way her performance was to be used).[213] Ultimately, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled en banc that Garcia enjoyed no copyright in her performance, rendering the question of license moot.[214] However, the different court opinions entertained various theories of implied license, including the possibility that Garcia had granted an implied license to the filmmakers and that the filmmakers had granted Garcia an implied license to perform the copyrighted screenplay.[215]

The ambiguity of written licenses together with the possibility of implied licenses creates a high likelihood of mistaken infringement due to misinterpretation of licenses. The user who violates the license after misreading or misunderstanding it clearly bears some responsibility for her infringement, but it does not make sense to treat her as culpable to the same degree as a willful infringer. We suggest that these cases belong under the category of “standard infringements.”

II. Copyright’s Liability Regime

As we have seen, copyright infringements involve different degrees of blameworthiness and impose varying degrees and types of harms on copyright owners. Nonetheless, the Copyright Act has a single standard of liability and a single standard compensatory scheme.

Liability under the Copyright Act is predicated on a strict liability standard. Neither the state of mind of the infringer nor her cost of avoidance matter for liability determinations. The roadmap for finding infringement, according to the Copyright Act, is simple and strict. Section 106 of the Act reserves to the owner of a copyright the exclusive right to perform certain actions, such as copying the work.[216] Section 501 of the Act, in turn, defines infringement as “violat[ing] any of the exclusive rights of the copyright owner.”[217] For courts, this language means that a person becomes an infringer if he or she performs one of the actions regarding the copyrighted work (such as copying) that the statute reserves for the owner, without a proper license from the copyright owner or from the statute itself.[218] Other than to be sure that the infringer actually knew of and somehow used (in a manner protected by § 106) the protected work, courts do not interest themselves in the state of mind of the infringer. Indeed, as Nimmer writes, “[r]educed to most fundamental terms, there are only two elements necessary to the plaintiff’s case in an infringement action: ownership of the copyright by the plaintiff and copying by the defendant.”[219]

Once infringement is established, the Copyright Act imposes a single standard compensatory scheme. Under § 504, all infringements that give rise to liability under § 501 entitle a copyright owner to recover her actual harm or the infringer’s profits—at her choice.[220] Likewise, all infringements entitle the plaintiff to seek injunctive relief.[221]

The only exception is statutory damages. If a copyright owner wishes to receive statutory damages in lieu of actual ones, courts must consider the blameworthiness of the defendant in setting statutory-damages awards.[222] Specifically, the Copyright Act sets forth three different categories of infringements—innocent, standard, and willful—and establishes a different recovery range for each category by varying the floor and the cap of the damages for each of the categories.[223]

In this Part, we explore this cookie-cutter liability regime by looking first at the strict liability standard for establishing whether an infringement has occurred; second, at the standardized remedies that apply to all infringements; and finally at the harm caused by standardized remedies. We also explore the unusual cases in which extant law permits tailoring remedies to the defendant’s culpability.

A. The Liability Standard

Liability under the Copyright Act arises whenever a person performs one of the exclusive acts granted to authors—namely, reproduces a work, adapts it, distributes it to the public, publicly performs or displays it or digitally performs it (in the case of sound recording), or authorizes such an act without permission from the rightsholder.[224] It is well established that the Act adopts a strict liability regime.[225] Acts are the touchstone of liability under the Act. The state of mind of the infringer is irrelevant.

It was not always like this. As Anthony Reese points out, historically, the Copyright Acts exempted innocent or unknowing infringements from liability.[226] He explains that “[t]he copyright system originally made most types of innocent infringement easily avoidable, and where innocent infringement was difficult to avoid the imposition of liability in fact depended on a defendant’s culpable mental state.”[227]

The 1976 Copyright Act, however, omits reference to the mental state of the infringer, and it does not reference the infringer’s degree of culpability. The Act’s definition of infringements is laconic; it simply states that any violation of an author’s exclusive right triggers liability.[228] The courts’ interpretation of the statutory language, however, premises liability on the purely objective standard of “copying in fact.”[229] This is not an accident. As Shyamkrishna Balganesh points out, “[d]ating back to its origins, copyright law has operated principally by granting its holder the exclusive right to copy a creative work of authorship, and actions for copyright infringement have ever since revolved entirely around a showing of copying.”[230]

Practically, as construed by the courts, liability does not even require positive proof of copying. Courts will suffice with circumstantial evidence of copying, relying on proof of “access” combined with “similarity.”[231] Concretely, a copyright owner who sues for infringement needs to show that the defendant had access to the putatively infringing work, in the sense that she was exposed to it or was likely to be exposed to it,[232] and that the defendant’s work bears similarity to that of the plaintiff.[233] Access and similarity, in other words, suffice as a replacement proof of actual copying. Once these twin elements have been established by the plaintiff, the defendant can defeat the presumption of copying by raising and proving the defense of “independent creation.”[234] And, while it is true that if a defendant can show that she did not copy her work from the plaintiff she should prevail in court,[235] a mere proof of access and similarity by a copyright holder suffices to shift the burden of proof to the defendant, who must show lack of copying. Failure on the part of the plaintiff to lift this burden will result in a finding of copying.

In fact, courts have construed liability under the Copyright Act so broadly as to cover cases where the court was satisfied that the infringer never consciously copied anything, as in the infamous case of Bright Tunes Music v. Harrisongs, mentioned previously.[236] In that case, as we noted, the court believed George Harrison’s testimony that he had not consciously copied anything from The Chiffons’ “He’s So Fine,” but the court still found the similarity so overwhelming as to support a finding of infringement.[237]

While casting the net of infringement widely, the statute recognizes only one type of infringement. The statute does not provide for degrees of infringement or for other categorizations of infringements. All infringements—whatever the circumstances giving rise to the violation of copyright rights—are seen by the statute as the same.

B. Remedies for Infringement

The civil remedies for infringement are laid out by § 504 of the Copyright Act, and for the most part, they are not differentiated by culpability. Monetary damages for an infringement come in three categories: the copyright owner’s “actual damages,” any “additional profits” of the infringer, and “statutory damages.”[238] In addition to the monetary damages, courts may award injunctive relief as “reasonable to prevent or restrain infringement,”[239] and it may order impoundment and destruction of infringing copies as well as articles by means of which the infringing copies could be produced.[240] In one very narrowly tailored set of circumstances the court can award a punitive “additional award of two times the amount of the license fee that the proprietor of the establishment concerned should have paid the plaintiff for such use during the preceding period of up to 3 years.”[241] Finally, the court may award costs and attorneys’ fees.[242]

The statute fails to provide clear guidelines for measuring the central building blocks of monetary damages—actual damages and lost profits. Actual damages are defined simply and unhelpfully as “the actual damages suffered by [the copyright owner] as a result of the infringement.”[243] Lost profits are defined, only slightly more helpfully, as “any profits of the infringer that are attributable to the infringement and are not taken into account in computing the actual damages.”[244] Section 504(b) adds the useful evidentiary rule that in calculating profits, gross revenues, as proved by the plaintiff, are presumptively equal to profits, and it is up to the defendant to attempt to reduce this amount by proving that the revenues were the result of something other than infringement, or that there were relevant deductible expenses.[245] Both heads of damage—actual damages and lost profits—are available in all cases of infringement, irrespective of culpability, unless the plaintiff elects to take statutory damages in their place.

It is only in a handful of instances that the Copyright Act looks in the direction of culpability.

First, there is a narrow punitive damages provision that relates to § 110(5) of the Act.[246] This exceedingly narrow provision is not easily explained. Section 110(5) of the Act, in relevant part, states that businesses may perform (“communicat[e]” to the public, in the language of the statute) nondramatic musical works subject to a variety of conditions.[247] Essentially, § 110(5) allows retail businesses, as well as bars and restaurants, to play the radio or television for their customers without getting a separate license from the owners of the copyrighted works being shown or played. Section 110(5) imposes very detailed and strict conditions on the businesses: they can only use the exemption if the business falls within certain size limitations (for instance, for an establishment other than a food service or drinking establishment, 2,000 gross square feet of space not including customer parking)[248] and uses certain equipment (for example, an establishment other than a food service or drinking establishment may use not more than four audiovisual devices, no more than one per room, and none with a diagonal screen size greater than fifty-five inches).[249] Section 504(d) states that where a defendant business owner claims that the infringement was justified by § 110(5), but the court concludes there were no “reasonable grounds” for the owner’s believing that the § 110(5) exemption applied, the court should add an additional, punitive damage award to any other damage award given by the court.[250] The punitive damage award is set by a fixed formula: “two times the amount of the license fee that the proprietor of the establishment concerned should have paid the plaintiff for [the nonexempt performances] during the preceding period of up to 3 years.”[251] It is difficult to know what to make of this narrow punitive damages provision or to understand why this one case warrants such exceptional treatment.

The second instance in which the Copyright Act adjusts remedies according to culpability is broader but limited solely to statutory damages. Statutory damages are available to plaintiffs only in lieu of actual damages and lost profits.[252] However, statutory damages may also be awarded punitively by the court in addition to actual damages and lost profits in cases where the “infringement was committed willfully.”[253] The Copyright Act generally provides that statutory damages may be elected by a prevailing copyright owner in the amount of $750–$30,000 (as the court deems just) in lieu of the actual damages and profits related to infringements of any work.[254] However, if the owner proves the infringement was committed willfully, the statutory damages may be increased to $150,000.[255]

This is the clearest use of culpability in the civil section of the Copyright Act,[256] but almost no guidelines are provided to courts in deciding what is willful and how to choose damages. In fact, while the Act provides that certain provisions of false information can create a rebuttable presumption of willfulness, it explicitly notes that this presumption should not be read more broadly to “limit[] what may be considered willful infringement.”[257] This lack of clarity has led scholars to criticize the statutory-damages provision as “frequently arbitrary, inconsistent, unprincipled, and sometimes grossly excessive” as applied by courts.[258]

The third and final instance in which civil remedies are adjusted for culpability similarly relates to statutory damages but operates in the opposite direction. Where courts find an infringer was innocent (i.e., the “infringer was not aware and had no reason to believe that his or her acts constituted an infringement of copyright”), the statutory damages may be reduced to as little as $200.[259] In some very narrow cases of infringement (an infringer who believed the use fell under the category of fair use, who was acting on behalf of a nonprofit educational institution, library, or public-broadcasting entity, and who also meets other restrictive conditions), the court is instructed to remit statutory damages.[260] The narrow remission provision is difficult to explain, but the broader structure of innocent infringement also appears without statutory guidance.

C. What’s Wrong with Uniform Standards of Liability

As we demonstrated, copyright doctrine contains a high degree of uncertainty. It is easy for potential users of a work to mistakenly infringe due to misunderstandings about the legal protections afforded works or the facts surrounding the work, such as ownership. At the same time, outside the arena of statutory damages, copyright remedies apply uniformly across the many types of infringements.

The uncertainty inherent in copyright law undermines its utilitarian goal of promoting expressive creativity. Ideally, the copyright system should be designed to maximize total expressive output at the lowest possible cost. This means that while copyright law should grant copyright owners the legal tools to force potential users to pay for licenses to use the works, the law should also aim to reduce costs of transacting about rights and enforcing them, as well as to reduce the effect of copyright-infringement actions in unnecessarily deterring follow-on creation. It is particularly important, therefore, that the Copyright Act adopt legal directives that minimize information costs to potential users of copyrighted works and, in particular, ameliorate the potential for overdeterrence that accompanies legal uncertainty.

As several leading law and economics scholars have pointed out, ambiguous legal doctrines invariably result in overdeterrence, which, in turn, prompts defendants to invest excessively in precautions.[261] The reason is simple. When facing a vague standard, actors cannot know for certain how much to invest in precautions taken in order to avoid liability. But they know that there is no symmetry between under- and over-investment. Underinvestment in precautions exposes one to the full brunt of civil (and criminal) liability. Overinvestment, by contrast, buys one immunity. Hence, under conditions of uncertainty, a rational actor would always choose to err on the side of safety and overinvest in precautions. Accordingly, the ambiguity of copyright law works as a one-way ratchet that will in many cases lead to the under-use of copyrighted works.

Users of copyrighted expression can respond to the vagueness of copyright law by adopting two types of precautions. When information and transaction costs are sufficiently low,[262] and users are aware of the copyrighted nature of the material they wish to use, users may attempt to secure a license from the copyright owner.[263] When information and transaction costs are high,[264] users will copy less protected expression than they are legally entitled to or refrain from using expression altogether. Importantly, the latter will lead users to forgo the use of not only legally protected copyrighted expression but also unprotected expression. This is because users will not always know whether expression is protected, but the cautious strategy is to respond to the lack of knowledge by avoiding use.