Qui Tam Tension: The Appropriate Standard of Review in Government-Requested FCA Dismissals

Qui tam actions brought under the False Claims Act present numerous questions of how to balance the interests of the government and the whistleblower—also called a relator—in accordance with our laws and

the Constitution. The unique relationship between the whistleblower and the government creates inherent tensions. One tension is evidenced by the current circuit split on the question of which standard of review courts should apply when the government moves to dismiss a qui tam action but the relator objects.

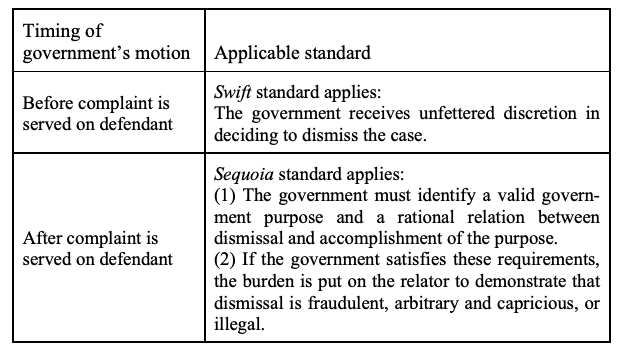

The circuits have come up with two primary standards. First, the unfettered discretion standard essentially gives the government prosecutorial discretion to dismiss a qui tam case at any stage of the litigation. Second, the rational relation standard requires that the government provide a reason for dismissal that is related to a government interest. The burden is then on the relator to demonstrate that dismissal is fraudulent, arbitrary and capricious, or illegal. The solution lies in the middle: consistent with the Constitution and federal law, the unfettered discretion standard should apply at the beginning of the action, before the complaint has been served on the defendant, and the rational relation standard should apply after service on the defendant.

No one has offered an examination of the question presented by the circuit split, much less proposed an answer. This Note provides the first discussion of both standards together and the first attempt at arguing for a solution.

Introduction

Whistleblowers have brought to light some of the biggest stories America has seen.[1] Most recently, it was whistleblowers who brought to light the questionable phone call between U.S. President Donald Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky that ultimately led to President Trump’s impeachment.[2] There are no clear incentives to come forward in most cases. Whistleblowers often face retaliation and receive little to no benefit from speaking out. However, when the wrongdoing affects the government’s interests, the government does provide incentives to blow the whistle. The False Claims Act (FCA) provides those incentives. Under the FCA, the government encourages whistleblowers to file lawsuits alleging false claims on behalf of the government by offering a percentage of any proceeds recovered.[3] These lawsuits are called qui tam actions.[4] The government has recovered billions of dollars from qui tam actions, which “comprise a significant percentage of the False Claims Act cases that are filed.”[5] In fiscal year 2019, whistleblowers—called relators in the context of qui tam suits—filed 633 lawsuits under the FCA.[6] These qui tam relators play an important role in the government’s efforts to protect itself from fraud.

Despite the success of these actions, the relationship between an individual’s right and the government’s interests in a civil action to which it is not a party creates tension. This tension is what makes the topic of this Note interesting. While this Note discusses a narrow issue under a specific statute, the tension at the heart of the question is one that is prevalent in many aspects of our legal system and lives.[7]

The tension in qui tam cases often depends on the form the action takes but is typically based in the question of control: who has control of the litigation and how much control or input is welcomed from the other side?[8] For example, “qui tam relators might insist on co-litigating the suit with [the Department of Justice] if DOJ decide[s] to intervene.”[9] This can be because the relator believes they can do a better job litigating the suit. The relator “might have a style or theory on the prosecution of the claim different from those of DOJ.”[10] These disagreements on how to proceed can make litigating these cases very difficult.[11]

The motivation for bringing the lawsuit is another area where tension can exist. In some cases, relators may be filing politically motivated suits or suits filed in an attempt to harass. These types of suits “would . . . subjugate DOJ to the whims of an empowered and self-interested private citizenry. Forced to investigate numerous qui tam suits, some frivolous and motivated by politics or retribution, DOJ would be wasting time and resources pursuing someone else’s agenda, rather than setting its own.”[12]

The usefulness of relators prosecuting qui tam cases on behalf of the government makes it necessary to find a balance, taking into account these tensions. Many provisions in the False Claims Act attempt to do that.[13] One of those provisions is § 3730(c)(2)(A). This provision states: “The Government may dismiss the action notwithstanding the objections of the person initiating the action if the person has been notified by the Government of the filing of the motion and the court has provided the person with an opportunity for a hearing on the motion.”[14] This provision, like many of the others that attempt to balance the government’s interests and the relator’s rights, has been challenged in court.[15]

Currently, there is a circuit split regarding what standard of review a court should apply to a request from the government to dismiss a qui tam case.[16] This split has primarily resulted in two standards: the Swift standard,[17] providing the government with unfettered discretion to dismiss a qui tam case; and the Sequoia standard,[18] requiring that the government show a rational relation between a governmental interest and the dismissal.

I argue that the standard of review applied in cases where the government moves to dismiss a qui tam case should be a hybrid approach. Swift’s unfettered discretion standard should apply to dismissal requests sought before the defendant has been served with the complaint, and Sequoia’s rational relation standard should apply to dismissal requests sought after the defendant has been served. This Note approaches this issue by first providing an overview of the qui tam framework in Part I. Next, in Part II the Note lays out the two standards of review developed by circuit courts. Part III examines the Granston Memo, a Department of Justice memo discussing the government’s approach to the FCA’s dismissal provision. And Part IV analyzes the two standards of review developed by the circuits, and concludes that the hybrid approach argued in this Note is consistent with constitutional and statutory understandings and the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. This hybrid standard successfully balances the tensions between individual rights and governmental authority.

I. Qui Tam Actions Under the False Claims Act

Qui tam actions are civil actions brought by a private person in the name of the federal government against any party who has attempted to defraud the government.[19] The False Claims Act provides the framework for these lawsuits.[20] Relators may bring qui tam actions alleging certain violations of law. The statute lays out the specific violations of law a qui tam relator can allege under the FCA.[21] These violations include, among others: knowingly presenting fraudulent claims for payment to the government, using a false record, and making a statement material to a fraudulent claim to the government.[22] The FCA was “originally aimed principally at stopping the massive frauds perpetrated by large contractors during the Civil War.”[23] Today, the government uses the FCA to fight fraud and false claims against the government in numerous contexts, most significantly in the health care industry.[24]

When a relator brings a lawsuit under the FCA, the proceedings can take one of two forms.[25] In the first, “the action shall be conducted by the Government” if the government chooses to proceed with the action itself. [26] In the alternative, the government declines to take over the action, “in which case the person bringing the action shall have the right to conduct the action.”[27] This right does not include unfettered control of the litigation by the relator, however. The government often continues to supervise these actions.[28] It also retains certain rights. Section 3730(c)(3) gives the government the right to “be served with copies of all pleadings filed in the action and [to] be supplied with copies of all deposition transcripts.”[29] The government can stay a relator’s discovery if the government shows “that certain actions of discovery by the [relator] would interfere with the Government’s investigation of prosecution of a criminal or civil matter arising out of the same facts.”[30] And perhaps most significantly, the court can “permit the Government to intervene at a later date upon a showing of good cause.”[31] This intervention would give the government primary control of the prosecution.[32]

No matter which route the qui tam action takes, the government retains the right under § 3730(c)(2)(A) to move for dismissal “notwithstanding the objections of the person initiating the action if the person has been notified by the Government of the filing of the motion and the court has provided the person with an opportunity for a hearing on the motion.”[33] Dismissal is also referenced in § 3730(b)(1), which states that an action by a relator “may be dismissed only if the court and the Attorney General give written consent to the dismissal and their reasons for consenting.”[34]

The FCA is silent on what standard of review courts should use when confronted with a motion for dismissal in a qui tam action. Circuit courts have interpreted the standard of review required by the FCA in two different ways.

II. The Circuit Split over Dismissals of Qui Tam Actions

The lack of statutory guidance forced the circuits to develop their own standards. Two main approaches have emerged: the unfettered discretion standard and the rational relation standard. The unfettered discretion standard was first developed in the D.C. Circuit in Swift v. United States, which held that the United States government has an “unfettered right” to dismiss a qui tam action.[35] In contrast, the Ninth Circuit in United States ex rel. Sequoia Orange Co. v. Baird–Neece Packing Corp. held that the United States government must identify a “valid government purpose” that is rationally related to dismissal.[36] The Tenth Circuit has also adopted this standard in certain circumstances.[37]

The Seventh Circuit, on the other hand, adopted a standard that “lies much nearer to Swift than Sequoia.”[38] The Seventh Circuit looked to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) to determine the standard.[39] The hybrid approach argued for in this Note does something similar, pulling from the dual approach found in the FRCP.[40] The Seventh Circuit’s decision and the hybrid approach are discussed in further detail in Part IV. It is first important to understand the primary standards in this area, the rational relation standard and the unfettered discretion standard.

A. Rational Relation Standard

In 1984, the Secretary of Agriculture issued marketing orders that limited the number of oranges and lemons citrus handlers could ship to market in Arizona and California.[41] Under the orders, citrus handlers who shipped oranges and lemons in excess of their designated allotment were subject to criminal fines and civil penalties.[42] A number of relators brought thirty-four qui tam actions—including the Ninth Circuit Sequoia case—against a number of citrus companies that “had . . . violated the [allotment] provisions of the orange and lemon marketing orders by over-shipping citrus and failing accurately to report, account and pay assessments for those overshipments.”[43]

Around the same time the relators filed their qui tam complaints, the government was filing its own claims against citrus industry growers and packinghouses, including the company at the center of the Sequoia case, Sequoia Orange Company.[44] “After discovering growing evidence of widespread [allocation] violations in the industry, the Secretary [of Agriculture] concluded that the [allotment] cheating reflected dissatisfaction with the citrus marketing orders, and that the orders had become divisive.”[45] As a result, the government decided to suspend the entire marketing program.[46] The government proposed settling all its own prosecutions and False Claims Act cases alleging violations of the marketing orders “to end industry turmoil.”[47] However, in 1994 the orange marketing orders were found by a district court to have been unlawfully promulgated and therefore invalid.[48] Settlement became less likely because the basis of the majority of the qui tam cases was the invalidated regulations.[49] The government decided that the best way to “clean the slate” was to seek dismissal of all qui tam cases using § 3730(c)(2)(A).[50]

In Sequoia, the government cited six reasons to support its motion to dismiss the qui tam case:

(1) to end the divisiveness in the citrus industry; (2) to facilitate a

new marketing order; (3) to terminate protracted and burdensome litigation; (4) to protect the United States’ taxpayers from continuing and escalating litigation expenses; (5) to curtail the drain on private resources resulting from the litigation; and (6) to allow the growers, agricultural cooperatives, handlers and others to work together in shaping new marketing tools.[51]

The district court granted the motion to dismiss after an evidentiary hearing. [52] The court found that the government’s wish to dismiss this qui tam action was “rationally related to a legitimate governmental purpose,” namely ending the ongoing war over the marketing program.[53] The qui tam relators appealed to the Ninth Circuit claiming that because their lawsuit had merit, the government could not seek dismissal.[54] The two-part standard for reviewing motions to dismiss filed by the government, developed by the district court, and affirmed by the Ninth Circuit, requires that the government first identify “a valid government purpose; and . . . a rational relation between dismissal and accomplishment of the purpose.”[55] Second, if the government satisfies these two requirements, the burden shifts to the relator “to demonstrate that dismissal is fraudulent, arbitrary and capricious, or illegal.”[56]

The district court decision in the Sequoia case further elaborated that the rational relation standard is still one that provides significant deference to the government. The district court held that, to establish a rational relation to a valid governmental purpose, “[t]here need not be a tight fitting relationship between the two; it is enough that there are plausible, or arguable, reasons supporting the agency decision.”[57] The Tenth Circuit in Ridenour v. Kaiser–Hill Co.[58] cited this language when it adopted the Sequoia standard for certain FCA qui tam situations.[59]

The relators in Ridenour were subcontractors who performed security at a government Superfund site.[60] The contractor, Kaiser-Hill, received the environmental cleanup contract for the site.[61] Part of the funds provided to Kaiser-Hill by the government were earmarked for security measures.[62] The relators who brought the case argued that Kaiser-Hill “either did not provide [the security measures] or provided [them] below acceptable levels,”[63] thereby taking the government’s money and not using it for its approved purpose—thus defrauding the government. After an investigation, the government decided not to intervene in the case but continued to monitor the progress of the suit.[64] However, eight months after the unsealing of the complaint and service on the defendant, the government filed a motion to dismiss.[65] The government cited two reasons for its motion. First, the lawsuit would potentially delay the cleanup and closure of the Superfund site.[66] And second, the lawsuit would compromise national security interests because it risked inadvertent disclosure of classified information.[67]

In discussing which standard to apply to the government’s motion to dismiss, the Tenth Circuit seemed to find significant the timing of the government’s motion—after the defendant has been served. The court construed “the hearing language of § 3730(c)(2)(A) to impart more substantive rights for a relator” when the government files the motion to dismiss after the defendant has been served.[68] The Tenth Circuit applied the Sequoia rational relation standard to these circumstances.[69] The court reasoned that the Sequoia standard “recognizes the constitutional prerogative of the Government under the Take Care Clause, comports with legislative history, and protects the rights of relators to judicial review of a government motion to dismiss.”[70]

B. Unfettered Discretion Standard

The D.C. Circuit, on the other hand, declined to adopt the Sequoia standard in any FCA dismissal situation.[71] Instead, in Swift v. United States, the D.C. Circuit held that the government has unfettered discretion to dismiss a qui tam action, and the judiciary therefore has essentially no role to play.[72]

The relator in Swift was a Department of Justice attorney.[73] The relator brought the qui tam action against one employee and two former employees of the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel.[74] The relator claimed that the Justice Department employees had conspired to defraud the government in violation of the False Claims Act.[75] Before service on the defendants, the government, without purporting to intervene, moved to dismiss the complaint on the grounds that the damages sought ($6,169.20) did not justify the expense of litigation.[76] After holding a hearing, the district court held for the government and dismissed the case.[77] The relator appealed on the grounds that “the government did not justify its decision to dismiss, [and] that dismissal was improper since the government did not investigate her claims,” among other things.[78]

The D.C. Circuit “hesitate[d] to adopt the Sequoia standard,” largely because it could not “see how § 3730(c)(2)(A) gives the judiciary general oversight of the Executive’s judgment [to dismiss a qui tam case].”[79] The court equated the government’s filing of a motion to dismiss to a governmental decision not to prosecute.[80] These decisions are presumed to be unreviewable.[81] In the D.C. Circuit’s view, § 3730(c)(2)(A) provides the government with what amounts to an “unfettered right to dismiss an action.”[82] Under the Take Care Clause of the Constitution, the court argued, the government “generally” has “absolute discretion” on “whether to bring an action on behalf of the United States,” and the FCA contains no language purporting to take that discretion away.[83] On the issue of the “opportunity for a hearing” included in § 3730, the court held that “the function of a hearing when the relator requests one is simply to give the relator a formal opportunity to convince the government not to end the case.”[84] In effect, when the government files a motion to dismiss a qui tam case the case is dismissed unless the relator changes the government’s mind at a hearing in court, a hearing where the judge has no decision-making role to play.

Although in Swift the defendants had not yet been served with the complaint,[85] the D.C. Circuit later applied Swift’s unfettered discretion interpretation of § 3730(c)(2)(A) to a case where the defendant received the complaint before the government moved to dismiss.[86]

III. The Government’s Approach to Dismissals

In a January 2018 memo (Granston Memo), the Department of Justice laid out the “Factors for Evaluating Dismissal Pursuant to 31 U.S.C. 3730(c)(2)(A).”[87] The memo begins by noting that there has been a record increase in FCA qui tam actions.[88] The government’s rate of intervention in these cases has “remained relatively static.”[89] The memo recommends that “when evaluating a recommendation to decline intervention . . . attorneys should also consider whether the government’s interests are served, in addition, by seeking dismissal.”[90] The government has historically been sparing in its use of § 3730(c)(2)(A).[91] This is largely because the text of the FCA specifically allows relators to proceed if the government declines to intervene.[92] “Moreover, a decision not to intervene in a particular case may be based on factors other than merit, particularly in light of the government’s limited resources.”[93] In limiting the use of § 3730(c)(2)(A), the government avoids blocking potentially worthwhile matters and ensures that “dismissal is utilized only where truly warranted.”[94]

Nonetheless, the government sees § 3730(c)(2)(A) as an “important tool to advance the government’s interests, preserve limited resources, and avoid adverse precedent.”[95] The Department of Justice sees itself as a gatekeeper of the False Claims Act because in qui tam cases where the government declines to intervene “the relators largely stand in the shoes of the Attorney General.”[96] Which is why, in the government’s opinion, the FCA provides the government with the authority to seek dismissal under § 3730(c)(2)(A).[97] The memo goes on to address when to exercise this authority. Although the “FCA does not set forth specific grounds for dismissal under section 3730(c)(2)(A),” the Granston Memo lists factors that the government can use as “a basis for evaluating whether [the government should] seek to dismiss future matters.”[98] The factors in the Memo are not an exhaustive list, but attempt to provide consistency across the Department of Justice concerning qui tam dismissals.[99] They include (1) curbing meritless qui tams, (2) preventing parasitic or opportunistic qui tam actions, (3) preventing interference with agency policies and programs, (4) controlling litigation brought on behalf of the United States, (5) safeguarding classified information and national security interests, (6) preserving government resources, and (7) addressing egregious procedural errors.[100]

These factors, however, are not relevant for legal purposes, the Memo argues, but simply for internal consistency.[101] The Department’s position is that the “appropriate standard for dismissal under section 3730(c)(2)(A) is the ‘unfettered’ discretion standard adopted by the D.C. Circuit rather than the ‘rational basis’ standard adopted by the 9th and 10th Circuits.”[102] Both standards, the government asserts, are intended to be highly deferential standards.[103] In an acknowledgment of the courts’ authority, the Memo notes that dismissal requests filed at a later stage in the proceeding run the risk of being ill-received by the court given the resources expended by the court and the parties.[104] “The court may also be less receptive to a motion filed at a later stage when doing so undercuts a claimed desire to avoid or reduce costs associated with discovery or safeguard information in discovery.”[105]

IV. The Hybrid Approach

I argue that a hybrid approach—applying both the Swift and Sequoia standards but at different points of the litigation—is the correct one. This approach is set out below:

The distinction between pre-service and post-service comes from the language of the FCA itself. Section 3730 requires the relator to provide

the government with a copy of the complaint.[106] From delivery of the complaint, the government has sixty days to determine if it wants to intervene.[107] The court can extend this time frame if the government shows good cause.[108] The complaint remains under seal during this time frame and is not served on the defendant.[109] These sixty days provide the government time to evaluate the lawsuit and the government’s resources to determine whether it is a case the government wants to prosecute.[110] If the government decides not to proceed with the action, “the person bringing the action shall have the right to conduct the action” moving forward.[111] At that point, the relator begins using its own resources to move forward litigating the case.

The hybrid approach is the correct approach because it is consistent with constitutional protections and statutory understandings. The hybrid approach balances the government’s prosecutorial discretion and the factors that go into a decision of whether to prosecute or not with the relator’s constitutional protections. The unique relationship created by the FCA presents a different situation than the typical prosecution. In most prosecutions, the government is the only one on the side of the prosecution putting resources into the case. No one is standing in the shoes of the government but the government itself. Because qui tam actions allow relators to stand in the shoes of the government and subsequently expend their own resources prosecuting the case, protections are necessary. The Sequoia rational relation standard provides a check on the government in an attempt to balance the relator’s efforts.

This Part discusses these arguments below, first addressing why the Swift unfettered discretion standard is the appropriate standard at the beginning of litigation and then addressing why the Sequoia rational relation standard is the appropriate standard after the complaint has been served on the defendant.

A. Argument for Application of the Swift Standard at the Beginning of Litigation

1. Consistent with Constitution and Understandings of Prosecutorial Discretion

It is consistent with the Take Care Clause of the Constitution to allow the government an initial time in which it has unfettered discretion to dismiss a qui tam case brought in the government’s name. The Take Care Clause of the Constitution entrusts the Executive with the duty to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”[112] This duty applies to the attorneys in the Justice Department who decide whether to bring cases against individuals who break the law.[113] “The decision whether to bring an action on behalf of the United States is therefore ‘a decision generally committed to [the government’s] absolute discretion.’”[114] The Swift court equated this decision in the qui tam context to prosecutorial discretion not to prosecute.[115]

Comparing the government’s motion to dismiss a qui tam case to prosecutorial discretion not to prosecute lends support for the unfettered discretion standard. Because the idea behind prosecutorial discretion is that the decision to bring an action on behalf of the United States is a decision generally committed to the government’s absolute discretion, “the presumption is that judicial review is not available.”[116] The basis of this discretion “is attributable in no small part to the general unsuitability for judicial review of agency decisions to refuse enforcement.”[117]

The reasons for this general unsuitability are present in the qui tam action situation as well as other prosecutorial situations. They include “a complicated balancing of a number of factors which are peculiarly within [the government agency’s] expertise.”[118] Balancing involves assessing “whether agency resources are best spent on this violation or another, whether the agency is likely to succeed if it acts, whether the particular enforcement action requested best fits the agency’s overall polices, and, indeed, whether the agency has enough resources to undertake the action at all.”[119] Relators bring qui tam cases on behalf of the government, so the government arguably retains the right to exercise its prosecutorial discretion, at least before the relator moves forward and spends his or her own resources litigating the case.

2. Statutory Language

Nothing in § 3730(c)(2)(A) “purports to deprive the Executive Branch of its historical prerogative to decide which cases should go forward in the name of the United States.”[120] The statute does not circumscribe the government’s authority to determine which cases it will pursue.[121] Section 3730 does not spell out limits on the government’s dismissal authority.

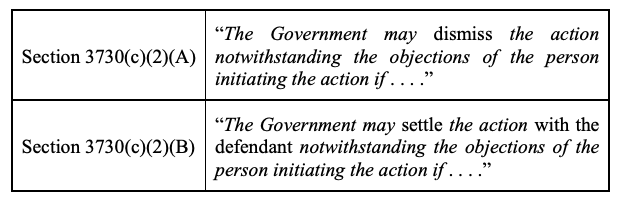

A comparison of two similar sections in the FCA provides insight into what standard of review Congress intended courts to apply to motions to dismiss. Sections 3730(c)(2)(A) and (B) provide the government with ability to take action “notwithstanding the objections of the person initiating the

action” with regard to two litigation-ending acts: dismissing and settling the lawsuit, respectively.[122] The language of both subsections begins essentially the same way:

However, the sections diverge after this beginning clause. Section 3730(c)(2)(A) goes on only to require the government to notify the relator of the filing and the court to provide the relator with an opportunity for a hearing.[123] On the other hand, § 3730(c)(2)(B) requires the court to determine “after a hearing, that the proposed settlement is fair, adequate, and reasonable under all the circumstances.”[124]

Because of this differential statutory treatment and lack of specific factors for the court to analyze, government-requested dismissals receive a higher level of deference than that which applies to settlements.[125] The statute does not ask the court to determine whether the dismissal is fair or reasonable in the language of the state.

3. Consistent with Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure were enacted to serve similar purposes to those the government holds out to be important in the context of qui tam litigation. The FRCP states that its purpose is “to secure the just, speedy, and inexpensive determination of every action and proceeding.”[126] These Rules are further relevant to the specific issue discussed in this Note because, like the hybrid standard, the Rules make a distinction based on the timing of when a plaintiff files a motion to dismiss.[127] This distinction provides a basis and support for the distinction made in the hybrid standard.

Under the FRCP, if a plaintiff files the motion to dismiss before the defendant files an answer or a motion for summary judgment, no involvement of the court is needed and the dismissal is automatic.[128] Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 41(a)(1), “Dismissal of Actions–Voluntary Dismissal–By the Plaintiff ,” allows a plaintiff to dismiss a civil action “without a court order by filing . . . a notice of dismissal before the opposing party serves either an answer or a motion for summary judgment.”[129] The thought that “no plaintiff should be forced to litigate against his will” is at the foundation of this rule.[130]

As the relator is bringing the suit “in the name of the Government”[131]—standing in the shoes of the government—it follows that the government should not be forced to litigate against its will. Applying the Swift unfettered discretion standard provides a similar right that FRCP 41(a)(1) provides. Although there is court involvement in that filing the motion is not automatic, the wide latitude given by the Swift standard is equivalent to FRCP 41(a)(1).

Further support for application of the FRCP in this way is provided by the Seventh Circuit. The court held that the appropriate standard when analyzing a motion to dismiss “is that provided by the [FRCP], as limited by any more specific provision of the False Claims Act and any applicable background constraints on executive conduct in general.”[132] The court reasoned that, although “[b]y itself, Rule 41(a) provides that ‘the plaintiff may dismiss an action,’ which obviously does not authorize an intervenor-plaintiff to effect involuntary dismissal of the original plaintiff’s claims. . . . § 3730(c)(2)(A) provides otherwise.”[133] The FCA specifically states that “[t]he Government may dismiss the action” without the relator’s consent as long as there is notice and an opportunity to be heard.[134] This statutory deviation is the only procedural limit on application of FRCP 41 in the Seventh Circuit’s opinion.[135]

B. Argument for Application of the Sequoia Standard After the Complaint Is Served

After the complaint has been served on the defendant, if the government moves for dismissal, the Sequoia rational relation standard should apply. Again, this standard first requires the government to identify a valid government purpose and a rational relation between dismissal and accomplishment of the purpose. And second, if the government satisfies these requirements, the burden is put on the relator to demonstrate that dismissal is fraudulent, arbitrary and capricious, or illegal.[136]

The Swift court itself admitted that the timing of when the government files a motion to dismiss could affect the government’s authority: “The government’s discretion to dismiss an action it has already brought may not be absolute . . . .”[137]

1. Consistent with Statutory Language and Notions of Coequal Branches of Government

Section 3730(c)(2)(A)’s requirement of an “opportunity for a hearing” when the government moves to dismiss indicates that there is at least some role for the courts to play in the decision to dismiss after the complaint has been served.[138] The D.C. Circuit argued that the hearing referenced in the statute is simply an opportunity for the relator to convince the government not to move forward with the dismissal.[139] However, if that were the case, it would be unnecessary for “the court” to be the one providing the opportunity for a hearing.[140]

If Congress intended the relator to have an opportunity to convince the government not to move forward with the dismissal, presumably Congress could have worded the statute to provide for that. The D.C. Circuit’s interpretation would make sense if Congress had enacted language like: “The relator shall have the opportunity to present to the government his or her opposition to the motion to dismiss.” But it did not. There is presumably no reason “the court” should be the one to “provide[] the [relator] with an opportunity for a hearing on the motion”[141] if the court has no role to play in the decision of whether or not to dismiss.

Therefore, accepting the unfettered discretion standard as applicable throughout the entire litigation would render the hearing requirement superfluous.[142] Rendering the hearing requirement superfluous violates a basic canon of statutory construction against superfluidity: “A statute should be construed so that effect is given to all its provisions, so that no part will be inoperative or superfluous, void or insignificant . . . .”[143] As a district court in Pennsylvania explained while adopting the Sequoia standard:

Requiring a hearing assures that the decision to dismiss is not arbitrary and without a valid governmental interest . . . . The Legislative Branch has delegated to the Executive Branch the authority to pursue the [FCA] actions with the relator. Requiring some justification, no matter how insubstantial, for a decision not to pursue a false claim, acts as a check against the Executive from absolving a fraudster on a whim or for some illegitimate reason. It prevents the Executive from abusing power.[144]

Application of the rational relation standard after the defendant has been served strikes a balance between the branches of government. It prevents the Executive from having unlimited power to dismiss a form of legal action the Legislature created. At the same time, it does not leave unchecked the power of the Judicial Branch to stop the Executive from dismissing an action. The Executive retains a significant amount of power through the application of the unfettered discretion standard at the beginning of litigation and even through the deferential rational relation standard at later points in litigation. In these ways the hybrid approach presented in this Note is consistent with the notion of independent, coequal branches of government.[145]

2. Consistent with Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

Like the application of the Sequoia standard post-service, the FRCP provides for judicial review of a motion to dismiss filed after litigation has begun in earnest. While Rule 41(a)(1)(A)(1) provides for no court involvement in motions to dismiss before the opposing party files an answer or a motion for summary judgment, Rule 41(a)(2) requires an order of the court “on terms that the court considers proper” if the plaintiff files the motion to dismiss after an answer or motion for summary judgment is filed by the opposing party.[146]

The thought behind the timing distinction in Rule 41 and the hybrid approach argued for in this Note is the same. At a certain point in the litigation, there is a need for judicial involvement in the dismissal process. In applying FRCP 41(a)(2) courts look at a number of questions, the first being whether dismissal is appropriate.[147] Although this calculus can involve numerous factors, the most relevant one is the amount of resources expended by the defendant.[148] For example, in a Florida district court case, a former student sued the university he previously attended for failing to accommodate his disability.[149] Over a year into the litigation and less than two months before trial was set to begin, the student fired his attorney and sought to dismiss the suit.[150] The court denied the student’s motion to dismiss, in part because the university had spent considerable resources in litigating the suit.[151] “If the defendant will suffer some plain prejudice other than the mere prospect of a second lawsuit, it is within the Court’s discretion to grant a voluntary dismissal without prejudice under Rule 41(a)(2), but such a dismissal is not a matter of right.”[152] In determining whether dismissal would prejudice the university, the court noted that “[the university] has expended considerable resources in litigating this suit up to now.”[153]

Similarly, in many qui tam suits, at the time the government seeks dismissal the relators have already expended considerable resources on the case. Obviously, the unique relationship of the qui tam action between the relator and the government presents a different scenario than the typical lawsuit. In a normal lawsuit the only two parties concerned with a motion to dismiss are the plaintiff and the defendant. In qui tam suits, analysis of these questions must also consider the interests of the relator. As a result, the courts’ efforts to avoid waste of the defendants’ resources when the plaintiff seeks voluntary dismissal is applicable to relators’ resources as well.

These factors support a role for the court after the complaint has been delivered. In those situations, a hearing under § 3730(c)(2)(A) provides the court with the opportunity to evaluate whether the government has identified a valid government purpose and a rational relation between dismissal and accomplishment of the purpose and if it has, whether the relator has demonstrated that dismissal is fraudulent, arbitrary and capricious, or illegal.[154] This is similar to the FRCP’s requirement that the dismissal be “proper.”

C. Practical Consequences

Adoption of the hybrid standard would provide benefits for both the government and relators.

1. Consequences for Relators and the Public

The hybrid standard fosters increased trust in government because applying the Sequoia standard fosters transparency.[155] Research shows that public trust in government is near historic lows.[156] In 2019, only 17% of Americans said they trusted the government in Washington to do what is right “just about always” (3%) or “most of the time” (14%).[157] In recent years, the Department of Justice has become increasingly politicized.[158] There are reports of the President’s friends being treated differently in Justice Department prosecutions. For example, President Trump’s friend Roger Stone reportedly received preferential treatment by the Justice Department.[159] In 2019, Stone was found guilty of “five counts of lying to Congress, one count each of witness tampering and obstruction of a proceeding,” all related to the investigation into Russian tampering in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.[160] Prosecutors originally recommended Stone’s sentence be seven to nine years, but Justice Department officials pressured them to decrease their recommended sentence. [161] The original prosecutors refused to do so because they believed the order was the result of political pressure from the President and resigned from the Justice Department in protest.[162]

This kind of abuse of power by the government is important in the context of qui tam cases because the qui tam mechanism is one of the primary means to root out corruption and fraud in America.[163] That is why application of the Sequoia standard, at least at some point in the proceeding, is significant. Requiring the government to be transparent about the reason it seeks dismissal “acts as a check against the Executive from absolving a fraudster on a whim or for some illegitimate reason. It prevents the Executive from abusing power.”[164]

Providing the court with the ability to inquire into the government’s motivations fosters faith in the judicial process. It reassures relators that there is a mechanism to prevent their time, energy, and money from being wasted because of the government’s unlawful whims. Without this assurance, fear that the government will dismiss a relator’s case solely for political reasons after time, energy, and money have been spent will discourage relators from bringing qui tam cases in the first place.

Further, the government articulating its reasoning may provide some solace to the relator. Even if the relator has spent significant resources on the litigation, the relator may respect the government more after being given an explanation. Knowledge that the government acts honorably fosters good relationships between relators and the Justice Department. Many relators are repeat players. If these relators believe the government is a trustworthy partner, they will be more likely to bring future cases of fraud to light.

2. Consequences for Government

Of course, adoption of the Sequoia rational relation standard as the sole standard would accomplish all of the above. Application of the Swift unfettered discretion standard, however—giving the government an opportunity to decide which cases to move forward without interference from the relator—is important for a number of reasons. First, the cases relators pursue reflect on the government. This can occur whether the government chooses to play an active role in the litigation or not. Allowing a relator to bring a case on the government’s behalf can be seen as an illustration of the government’s priorities. The initial unfettered discretion given to the government under the hybrid standard allows the government to be in control of setting its own priorities. This is important not just because of the public-facing nature of priority setting, but also because resources are often limited.

Although the Justice Department’s budget is often large,[165] there are undoubtedly resource-allocation decisions that have to be made. Qui tam cases draw Justice Department resources, even when the government chooses not to take an active role.[166] Because of the nature of the qui tam relator standing in the government’s shoes, the government must spend resources monitoring the litigation and sometimes must produce discovery.[167] The ability to decide which cases go forward in its name gives the government the ability to conform to those budgetary constraints.

Lastly, an opportunity for unfettered discretion allows the government to avoid cases that may result in “adverse decisions that affect the government’s ability to enforce the FCA.”[168] The precedent made by qui tam cases is law that will apply to the government in its own FCA prosecutions. There may be cases in which the government sees the potential for a case to create bad law, but the relator is only concerned about their one prosecution. With unfettered discretion initially, the government has the ability to protect the bigger picture.

Conclusion

As President Obama once wrote: “Often the best source of information about waste, fraud, and abuse in government is an existing government employee committed to public integrity and willing to speak out. Such acts of courage and patriotism, which can sometimes save lives and often save taxpayer dollars, should be encouraged rather than stifled.”[169] Our justice system should encourage qui tam actions because they are a useful component of the system. But there is a balance that must be struck between protecting individuals’ rights and maintaining the government’s authority.

The unique relationship created by the False Claims Act creates unique legal

questions. On the question of which standard the courts should use when the government seeks dismissal of a qui tam case, utilizing both the Swift unfettered discretion standard—before complaint service on the defendant—and the Sequoia rational relation standard—after complaint service on the defendant—balances the concerns presented. The hybrid approach relieves some of the tensions present in the qui tam relationship and ensures fairness for both the individual relators and the government.

- .See David Cohen, 10 Famous/Infamous Whistleblowers, Politico (Aug. 14, 2013,

11:15 PM), https://www.politico.com/gallery/2013/08/10-famous-infamous-whistleblowers-001083?slide=0 [https://perma.cc/XQ7V-GKLL] (describing revelations of whistleblowers which became big news stories). ↑ - .Tara Law, A Second Whistleblower on the Ukraine–Trump Call Has Come Forward, Lawyer for First Whistleblower Confirms, Time (Oct. 6, 2019, 12:28 PM), https://time.com/5693833/second-whistleblower-trump-ukraine/ [https://perma.cc/3QBH-NQNK]. ↑

- .31 U.S.C. § 3730(d)(1)–(2) (2012) (providing that whistleblowers should receive 15–25% of the proceeds of the action if the government proceeded with the action and 25–30% of the proceeds if the government did not proceed with the action); Justice Department Recovers over $3 Billion from False Claims Act Cases in Fiscal Year 2019, Dep’t Just. (Jan. 9, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-recovers-over-3-billion-false-claims-act-cases-fiscal-year-2019 [https://perma.cc/8P9B-A29H] [hereinafter DOJ Recovery Press Release]. ↑

- .See 31 U.S.C. § 3730 (designating suits brought by private parties on behalf of the government as “qui tam actions”). ↑

- .DOJ Recovery Press Release, supra note 3. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .For example, qualified immunity cases present a similar tension. See Editorial Board, How the Supreme Court Lets Cops Get Away with Murder, N.Y. Times (May 29, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/29/opinion/Minneapolis-police-George-Floyd.html [https://perma.cc/W942-V7QT] (discussing qualified immunity in the context of police officers’ authority violating individuals’ rights). ↑

- .See, e.g., 31 U.S.C. § 3730(b)(4) (granting the government certain control by permitting the government to choose whether to proceed with the qui tam action itself or to let the relator proceed on their own). ↑

- .Michael Lawrence Kolis, Settling for Less: The Department of Justice’s Command Performance Under the 1986 False Claims Amendments Act, 7 Admin. L.J. Am. U. 409, 428 (1993). ↑

- .Id. at 429. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 430 (alterations omitted). ↑

- .See 31 U.S.C. § 3730(b)(3) (giving the government the ability to receive an extension to decide whether or not to intervene); id. § 3730(c)(2)(A) (giving the government the ability to seek dismissal notwithstanding the objections of the relator); id. § 3730(c)(2)(B) (giving the government the ability to settle the action notwithstanding the objections of the relator if the settlement is fair, adequate, and reasonable); id. § 3730(c)(2)(C) (giving the government the ability to limit the relator’s involvement when the government chooses to intervene); id. § 3730(c)(3) (giving the government the ability to intervene later in the case upon a showing of good cause). ↑

- .Id. § 3730(c)(2)(A). ↑

- .Many FCA issues have in fact reached the Supreme Court. See Cochise Consultancy, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Hunt, 139 S. Ct. 1507, 1511–12 (2019) (holding that private qui tam actions, not just government-initiated suits, are entitled to the extended statute of limitations period in the FCA); State Farm Fire & Cas. Co. v. United States ex rel. Rigsby, 137 S. Ct. 436, 442–43 (2016) (holding the trial court has the discretion to dismiss a relator’s complaint when the FCA’s seal provision is violated); Universal Health Servs., Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar, 136 S. Ct. 1989, 1995–96 (2016) (answering numerous FCA questions); Kellogg Brown & Root Servs. Inc. v. United States ex rel. Carter, 135 S. Ct. 1970, 1978–79 (2015) (holding, in part, that the FCA’s first-to-file bar applies only to pending cases, which does not include cases previously dismissed). ↑

- .Compare Swift v. United States, 318 F.3d 250, 252 (D.C. Cir. 2003) (applying an unfettered discretion standard), with United States ex rel. Sequoia Orange Co. v. Baird–Neece Packing Corp., 151 F.3d 1139, 1145 (9th Cir. 1998) (applying a rational relation standard). ↑

- .Swift, 381 F.3d at 252. ↑

- .Sequoia Orange Co., 151 F.3d at 1145. ↑

- .31 U.S.C. § 3730(b). ↑

- .See id. § 3730 (listing the requirements to bring qui tam suits). ↑

- .Id. § 3729(a)(1). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .United States v. Bornstein, 423 U.S. 303, 309 (1976). ↑

- .DOJ Recovery Press Release, supra note 3 (stating that of the more than $3 billion recovered in Fiscal Year 2019, $2.6 billion was related to health care industry matters). ↑

- .31 U.S.C. § 3730(b)(4). ↑

- .Id. § 3730(b)(4)(A). ↑

- .Id. § 3730(b)(4)(B). ↑

- .Michael D. Granston, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Factors for Evaluating Dismissal Pursuant to 31 U.S.C. 3730(c)(2)(A) (2018). ↑

- .31 U.S.C. § 3730(c)(3). ↑

- .Id. § 3730(c)(4). ↑

- .Id. § 3730(c)(3). ↑

- .Id. § 3730(c)(1). ↑

- .Id. § 3730(c)(2)(A). ↑

- .Id. § 3730(b)(1). ↑

- .318 F.3d 250, 252 (D.C. Cir. 2003). ↑

- .United States ex rel. Sequoia Orange Co. v. Baird-Neece Packing Corp. 151 F.3d 1139, 1145 (9th Cir. 1998). ↑

- .Ridenour v. Kaiser-Hill Co., 397 F.3d 925, 936 (10th Cir. 2005). ↑

- .United States ex rel. Cimznhca, LLC v. UCB, Inc., 970 F.3d 835, 840 (7th Cir. 2020). ↑

- .Id. at 849–50. ↑

- .See infra Part IV. ↑

- .Sequoia Orange Co., 151 F.3d at 1142. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 1141–42. ↑

- .Id. at 1142. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 1142–43. ↑

- .Id. at 1143. ↑

- .Id. at 1141 (citing United States ex rel. Sequoia Orange Co. v. Sunland Packing House Co., 912 F. Supp. 1325 (E.D. Cal. 1995)). ↑

- .Id. at 1143. ↑

- .Id. at 1145 (quoting United States ex rel. Sequoia Orange Co. v. Sunland Packing House Co., 912 F. Supp 1325, 1341 (E.D. Cal. 1995)). ↑

- .Id. (quoting United States ex rel. Sequoia Orange Co. v. Sunland Packing House Co., 912 F. Supp 1325, 1347 (E.D. Cal. 1995)). The Ninth Circuit calls its standard a “two-step test” with reference only to the requirements of the government before the burden is shifted—(1) identification of a valid government purpose and (2) a rational relation between dismissal and accomplishment of the purpose. Id. This Note refers to a two-part standard that does not break up what the government must show and includes the relator’s burden as well. See infra Part IV. ↑

- .United States ex rel. Sequoia Orange Co. v. Sunland Packing House Co., 912 F. Supp 1325, 1341 (E.D. Cal. 1995) (quotations omitted). ↑

- .397 F.3d 925 (10th Cir. 2005). ↑

- .Id. at 937. ↑

- .Id. at 929. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 929–30. ↑

- .Id. at 930. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 935. ↑

- .Id. at 936. However, it remains an open question in the Tenth Circuit whether Sequoia’s rational relation standard or Swift’s unfettered deference standard (discussed below) provides the proper scope of judicial review in cases where the government seeks to dismiss an action before the defendant has been served and where the government did not intervene in the action. See United States ex rel. Wickliffe v. EMC Corp., 473 F. App’x 849, 852–53 (10th Cir. 2012) (holding that under either standard “the government’s motion to dismiss passes muster”). ↑

- .Ridenour, 397 F.3d at 936. ↑

- .Swift v. United States, 318 F.3d 250, 252 (D.C. Cir. 2003). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 250. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 250–51. ↑

- .Id. at 251. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 252. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. (citing Heckler v. Chaney, 470 U.S. 821, 831–33 (1985)). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 253 (quoting Heckler, 470 U.S. at 833). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 251. ↑

- .Hoyte v. Am. Nat’l Red Cross, 518 F.3d 61, 64–65 (D.C. Cir. 2008). ↑

- .Granston, supra note 28. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 2. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 2–3. ↑

- .Id. at 2. ↑

- .Id. at 3–7. ↑

- .Id. at 2. ↑

- .Id. at 7. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 8. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .31 U.S.C. § 3730(b)(2) (2012). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. § 3730(b)(3). ↑

- .Id. § 3730(b)(2). ↑

- .See id. § 3730(b)(4) (stating that before the sixty-day period is up the government shall proceed with the action or decline to take over the action). ↑

- .Id. § 3730(b)(4)(B). ↑

- .U.S. Const. art. II, § 3. ↑

- .See Swift v. United States, 318 F.3d 250, 253 (D.C. Cir. 2003) (citing the Take Care Clause as the basis for prosecutorial discretion). ↑

- .Id. ( quoting Heckler v. Chaney, 470 U.S. 821, 831 (1985)) (alteration in original). ↑

- .Id. at 252 (citing Heckler, 470 U.S. at 831–33). ↑

- .Heckler, 470 U.S. at 831. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Swift, 318 F.3d at 253. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .31 U.S.C. §§ 3730(c)(2)(A)–(B). ↑

- .Id. § 3730(c)(2)(A). ↑

- .Id. § 3730(c)(2)(B). ↑

- .United States v. Everglades Coll., Inc., 855 F.3d 1279, 1288 (11th Cir. 2017). ↑

- .Fed. R. Civ. P. 1. ↑

- .Fed. R. Civ. P. 41(a)(1)(A)(i). ↑

- .Thorp v. Scarne, 599 F.2d 1169, 1171 n.1 (2d Cir. 1979). ↑

- .Fed. R. Civ. P. 41(a)(1)(A)(i) (emphasis added). ↑

- .See Erie-Lackawanna R.R. Co. v. United States, 279 F. Supp. 303, 307 (S.D.N.Y. 1967) (suggesting that forcing a plaintiff to litigate against their will is rare). ↑

- .31 U.S.C. § 3730(b)(1) (2012). ↑

- .United States ex rel. Cimznhca, LLC v. UCB, Inc., 970 F.3d 835, 849 (7th Cir. 2020). ↑

- .Id. at 850 (citations omitted). ↑

- .Id. (citing 31 U.S.C. § 3730(c)(2)(A)). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .See supra subpart II(A). ↑

- .Swift v. United States, 318 F.3d 250, 253 (D.C. Cir. 2003) (citing Rinaldi v. United States, 434 U.S. 22, 30 (1977)) (pointing out that, when the court defers to the government’s decision to move for dismissal, it still “presume[s] the Executive is acting rationally and in good faith”). ↑

- .See 31 U.S.C. § 3730(c)(2)(A) (requiring that the court give the relator an opportunity for a hearing). ↑

- .Swift, 318 F.3d at 253. ↑

- .See 31 U.S.C. § 3730(c)(2)(A) (stating the government may dismiss the qui tam action after the court “has provided the [relator] with an opportunity for a hearing on the motion”). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Cf. Nat’l Ass’n of Mfrs. v. Dep’t of Def., 138 S. Ct. 617, 632 (2018) (declining to follow the government’s interpretation of a statute when the interpretation resulted in superfluidity). ↑

- .Hibbs v. Winn, 542 U.S. 88, 101 (2004). ↑

- .United States v. EMD Serono, Inc., 370 F. Supp. 3d 483, 488–89 (E.D. Pa. 2019). ↑

- .See id. at 489 (arguing that the rational relation standard is consistent with the notions of independent, coequal branches of government). ↑

- .Fed. R. Civ. P. 41(a)(1)(A)(i); Fed. R. Civ. P. 41(a)(2). ↑

- .Hubbard v. United States, 545 F. Supp. 2d 1, 7 (D.D.C. 2008). ↑

- .See id. (noting that dismissal was not allowed because the government had expended time and resources diligently defending the action); Tikkanen v. Citibank (South Dakota) N.A., 801 F. Supp. 270, 273 (D. Minn. 1992) (holding that dismissal was not allowed where defendant had committed substantial resources to the case). ↑

- .Witbeck v. Embry Riddle Aeronautical Univ., Inc., 219 F.R.D. 540, 541 (M.D. Fla. 2004). ↑

- .Id. at 541–42. ↑

- .Id. at 542. ↑

- .Id. (citations omitted) (quotations omitted). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .See United States ex rel. Cimznhca, L.L.C. v. UCB, Inc., 970 F.3d 835, 851 (7th Cir. 2020) (positing that “a hearing under § 3730(c)(2)(A) could serve to air what terms of dismissal are ‘proper’” under the FRCP). ↑

- .United States ex rel. Harris v. EMD Serono, Inc., 370 F. Supp. 3d 483, 488 (E.D. Pa. 2019) (using this reasoning in adopting the Sequoia standard to apply to all government motions to dismiss in qui tam litigation). ↑

- .Public Trust in Government: 1958–2019, Pew Res. Ctr. (Apr. 11, 2019), https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/04/11/public-trust-in-government-1958-2019/ [https://perma

.cc/M64Q-K658]. ↑ - .Id. ↑

- .See, e.g., Nicholas Fandos, Charlie Savage & Katie Benner, Roger Stone Sentencing Was Politicized, Prosecutor Plans to Testify, N.Y. Times (June 23, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/23/us/politics/roger-stone-sentencing-politicized.html [https://perma.cc/ZEX6-EZYN] (stating that what the Stone prosecutor “heard—repeatedly—was that Roger Stone was being treated differently from any other defendant because of his relationship to the president”); Spencer S. Hsu, Devlin Barrett & Matt Zapotosky, Justice Dept. Moves to Drop Case Against Michael Flynn, Wash. Post (May 7, 2020, 8:34 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/legal-issues/justice-dept-moves-to-void-michael-flynns-conviction-in-muellers-russia-probe/2020/05/07/9bd7885e-679d-11ea-b313-df458622c2cc_story.html [https://perma.cc/BTG8-URD3] (explaining that the Justice Department moved to drop charges against the President’s former national security adviser after he pled guilty to lying to the FBI). ↑

- .Ali Dukakis & Alexander Mallin, Entire Roger Stone Prosecution Team Withdraws After DOJ Lowers Sentencing Recommendation, ABC News (Feb. 11, 2020, 6:11 PM), https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/prosecutors-call-lower-sentence-roger-stone-trump-denies/story?id=68893294 [https://perma.cc/NV5S-5VWX]. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id.; Jonathan Kravis, I Left the Justice Department After It Made a Disastrous Mistake. It Just Happened Again, Wash. Post (May 11, 2020, 8:00 AM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/05/11/i-left-justice-department-after-it-made-disastrous-mistake-it-just-happened-again/ [https://perma.cc/R2NC-23HC]. ↑

- .See Kravis, supra note 161 (discussing the Justice Department’s abandonment of its “responsibility to do justice”). ↑

- .See DOJ Recovery Press Release, supra note 3 (discussing the billions of dollars recovered from qui tam actions, which “comprise a significant percentage of the False Claims Act cases filed”). ↑

- .United States ex rel. Harris v. EMD Serono, Inc., 370 F. Supp. 3d 483, 488–89 (E.D. Pa. 2019). ↑

- .Jane Edwards, House Panel Unveils $71.5B FY 2021 Funding Bill for DOC, DOJ, NADA, NSF, Exec. Gov. (July 8, 2020), https://www.executivegov.com/2020/07/house-panel-unveils-715b-fy-2021-funding-bill-for-doc-doj-nasa-nsf/ [https://perma.cc/5KTV-SVLB] (stating DOJ is set to get $33.2 billion in FY 2021). ↑

- .Granston, supra note 28, at 1. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Joe Davidson, Joe Davidson’s Federal Diary: Whistleblowers May Have a Friend in Oval Office, Wash. Post (Dec. 11, 2008), https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/12/10/AR2008121003364_2.html [https://perma.cc/8XS9-2A97]. ↑