Designing Designer Bankruptcy

Introduction

Earplugs. That’s the subject of the largest litigation in the history of American courts—230,000 lawsuits alleging that Aearo, a subsidiary of the corporate giant 3M, provided defective earplugs to the United States military.[1] Unsurprisingly, those lawsuits have been consolidated and, unsurprisingly, that consolidation took the form of multidistrict litigation,[2] the landing ground for much of today’s mass-tort litigation.

What’s surprising is where the Aearo litigation is now: bankruptcy court. And what’s more surprising is why: Aearo decided that the multidistrict litigation was a “failure,” marred by “outsized verdicts,” claims that “ha[d] never been vetted,” a “litigation vortex,” and a “flawed bellwether trial process.”[3] So it simply filed for bankruptcy.[4]

And Aearo is not alone. Mass-tort defendants today are routinely opting into bankruptcy, from Purdue Pharma to the Boy Scouts to PG&E.

But today’s migration of mass torts from multidistrict litigation to bankruptcy is not just about defendants’ dissatisfaction with multidistrict litigation. Rather, it coincides with the rise of “designer bankruptcy”—the ability of large businesses to pick and choose which of their assets and liabilities land in bankruptcy court and which remain outside of bankruptcy.

Take Johnson & Johnson, the defendant in 38,000 lawsuits alleging that its talc powder caused cancer.[5] It too thought little of multidistrict litigation, writing of “well-documented abuses that occur in the state court tort system,” “inconsistent and excessive awards,” and “the costs associated with the continued litigation.”[6] But instead of filing for bankruptcy itself, Johnson & Johnson availed itself of designer bankruptcy. Specifically, it put its tort liability in bankruptcy and left its business operations outside bankruptcy.[7] To do so, Johnson & Johnson created a subsidiary, LTL Management, to house all that tort liability (but none of the business’s assets) and had LTL Management file for bankruptcy.[8] Meanwhile, the rest of Johnson & Johnson’s business continues to operate normally outside of bankruptcy.

This Article unpacks such designer bankruptcies. It begins by tracing their evolution, then it offers a new theoretical framework for understanding their design, and it concludes by suggesting solutions for Congress (and failing that, courts) for taking advantage of the promise of designer bankruptcy without running into its pitfalls.

That evolution began in asbestos bankruptcies in the 1980s. The sheer size of those bankruptcies and the effect of asbestos on dozens of major businesses called for a creative solution. And thus, designer bankruptcy was born.

The pioneer was the Johns-Manville Corporation (Manville)—at the time, the world’s largest asbestos manufacturer. It faced thousands of lawsuits alleging that its products caused cancer.[9] And it filed for bankruptcy to manage the deluge of lawsuits—hundreds every month, with estimated liabilities running into the billions.[10]

In bankruptcy, Manville underwent the “corporate mitosis”[11] that is the hallmark of designer bankruptcy. It split the legacy Manville in two, creating a Trust and a successor corporation.[12] The Trust operated for the benefit of tort victims and housed all tort liability (via an injunction channeling all tort claims to the Trust) along with assets to compensate those tort victims.[13] The successor corporation received the remaining assets, including those used to operate the business, and all other business-related liabilities. The Trust went on to set up an administrative process to handle tort claims and compensate victims, much like a workers’ compensation scheme.[14] And the successor corporation continued carrying on Manville’s business operations, free of tort litigation and tort liability.

Congress viewed Manville’s innovation as a good model for managing asbestos mass torts, which, at the time, clogged the federal courts. So Congress codified the Manville Model as § 524(g) of the Bankruptcy Code, turning corporate mitosis into the standard way of handling hundreds of thousands of claims in tens of thousands of lawsuits and dozens of asbestos business bankruptcies.[15] In turn, dozens of asbestos bankruptcies used § 524(g), and tens of billions of dollars of assets were placed in Manville Model trusts to compensate tort victims.[16]

As § 524(g) grew in popularity, innovative debtors began to plan those bankruptcies in advance. These prepackaged asbestos bankruptcies would negotiate a § 524(g) plan and then file for bankruptcy.[17] At filing, the court would be presented with a § 524(g) plan that had already received votes and was ready to be confirmed on the spot.[18] That minimized time in bankruptcy (months, not years), streamlining the complex process of reorganizing debtors with mass asbestos liability.

The most recent innovation in designer bankruptcy, the Texas Two-Step, minimizes time in bankruptcy even more by having the business avoid bankruptcy altogether. Essentially, it recreates the Manville Model’s corporate mitosis, but it does so out of bankruptcy.

The first step is for the mass-tort defendant to undergo a “divisional merger,” typically under Texas law.[19] In a divisional merger, the legacy company (here, our mass-tort defendant) splits in two, allocating its assets and liabilities as it pleases between the two new companies.[20] In a Texas Two-Step, the divisional merger allocates all mass-tort liability to one new entity (LiabilityCo) and all business assets to another new entity (AssetCo).[21] A funding agreement between AssetCo and LiabilityCo promises that AssetCo will pay the costs of bankruptcy and whatever amount a bankruptcy court determines that LiabilityCo owes tort victims.[22]

The second step is for LiabilityCo, and only LiabilityCo, to file for bankruptcy. That way, through AssetCo, the mass-tort defendant keeps its entire business operations in one legal entity (as with Manville’s successor corporation), but that legal entity is never subject to the strictures of bankruptcy law.

These designer bankruptcies mark a shift in how bankruptcy does design. To be sure, scholars, going back to the 1980s, have identified uses of design in bankruptcy. Steven Schwarcz, for example, detailed how corporate structures can be (and are) used to create special-purpose entities that are, in effect, bankruptcy-proof.[23] Douglas Baird and Anthony Casey described a similar mechanism of corporate design to keep critical productive assets for an enterprise in separate corporations, creating a “withdrawal right” from bankruptcy for those assets should the enterprise as a whole fail.[24] Lynn LoPucki wrote that such maneuvers (along with other secured-debt and ownership strategies) could lead to the “death of liability,” whereby corporate assets are placed beyond the reach of corporate creditors, rendering the corporate entity that commits a tort judgment proof even though the rest of the corporate family retains its assets.[25]

But design today is the inverse of bankruptcy proofing, withdrawal rights, and the death of liability. Designer bankruptcies for today’s mass torts focus on after-the-fact design, not advanced planning. And they aim to put certain liabilities in bankruptcy rather than shield certain assets from it.

That shift in design also militates a shift in our understanding of mass-tort bankruptcy. Indeed, the critical insight about these “designer bankruptcies” is that they are not primarily about bankruptcy law.[26] They are not aimed at using bankruptcy to discharge liability or reorganize a business.

Instead, these designs sound in organizational law—the law of legal entities like corporations, trusts, and partnerships. Specifically, these designer bankruptcies are about asset partitioning, regulatory partitioning, and governance across legal entities. Bankruptcy just happens to be a convenient, and perhaps the only, body of law to achieve the needed organizational law maneuvers.

Take asset partitioning. As Henry Hansmann and Reinier Kraakman explain, asset partitioning is “creati[ng] . . . a pattern of creditors’ rights,” that is, designating distinct pools of assets for distinct creditors.[27] By way of example, when a corporation creates a subsidiary, creditors of the subsidiary know that they can access the subsidiary’s assets for repayment (but not the corporation’s), and they also know that creditors of the corporation will be able to access the corporation’s assets (but not the subsidiary’s).[28]

This is the same maneuver in designer bankruptcy—business creditors are designated one pool of assets (like Manville’s successor corporation); tort creditors are designated another (like Manville’s Trust). That is an asset partition, not a matter of bankruptcy law. Bankruptcy law happens to be a convenient mechanism for achieving that asset partition because bankruptcy acts after the liability has been incurred and thus can achieve ex post asset partitioning.

Next, consider regulatory partitioning. As Mariana Pargendler writes, regulatory partitioning is the use of legal entities as a “nexus for regulation.”[29] Thus, for example, a French corporation may set up an American subsidiary with American citizenship if an American regulatory regime forbids certain transactions with foreign corporations.[30] Such partitions enable legal entities to opt into regulatory benefits and opt out of regulatory burdens.

In designer bankruptcy, there are three uses of regulatory partitions.[31] The first allows the tort victims’ entity (like the Manville Trust) to establish an administrative scheme for compensation.[32] The second keeps creditors, and their collection efforts, in bankruptcy (for both a Manville trust and the Two-Step LiabilityCo). And the third keeps business assets outside of bankruptcy (like the Two-Step AssetCo).

The first partition uses bankruptcy to create what is essentially a workers’ compensation system for resolving mass torts.[33] The aim is to create a system of claims resolution that is cheaper than litigation, more reliant on expertise, and more consistent across victims. That, as with asset partitions, has nothing to do with bankruptcy law. But bankruptcy allows a court to impose such a scheme through a Chapter 11 plan that creates a tort trust for mass-tort victims. Hence, bankruptcy law is a convenient body of law for achieving that partition.

The second partition aims to subject creditors to both bankruptcy’s burdens and its benefits. Keeping creditors in the bankruptcy court has the benefit of coordinating their collection efforts. It also prevents them from dismembering a viable business, leaving more of the business’s value for victims. The burden is a loss of control for individual creditors. This is the standard tradeoff of bankruptcy and the only true bankruptcy role that designer bankruptcy invokes.[34]

The third partition is specifically aimed at avoiding any bankruptcy burdens for operating a business. It appears only in the Texas Two-Step, which takes advantage of the “bankruptcy partition” by keeping the operating business outside of bankruptcy entirely.[35] The result of that escape from bankruptcy is smoother functioning of the business and an easier reorganization.

The final organizational-law element in these designer bankruptcies is governance. As Robert Sitkoff writes, these are “rules that provide for the powers and duties of the managers and the rights of the beneficial owners.”[36] Splitting one entity into two necessarily raises questions of governance for both entities as well as the relationship between them. And the aim is to ensure that each entity is run by those with both the ability to run it and the right loyalties.

In a situation like Manville, governance works well. Old management run the successor corporation and have the expertise to do so. They are also loyal to shareholders, which in the Manville case includes the trust, so management are maximizing value for the tort victims. As for the trust, it too is loyal to tort victims (who are the beneficiaries of the trust) and has the information needed to oversee the successor corporation. That prevents maneuvers by the successor corporation that might give the tort victims short shrift. The trustees also have the expertise to set up a compensation scheme for tort victims, ensuring that victims receive what they are owed.

But for the Two-Step, governance can pose problems for the tort victims. Management of AssetCo are loyal to shareholders, but here, unlike a Manville successor corporation, the tort victims own no shares. Thus, their expertise, while increasing AssetCo’s value, does not aim to benefit tort victims, but instead to benefit AssetCo’s old shareholders. Likewise, LiabilityCo’s management will be chosen before bankruptcy by AssetCo based on their loyalty to AssetCo shareholders.[37] So no one in a Texas Two-Step is looking out for the interests of tort victims. And even the bankruptcy judge, who is not beholden to shareholders, can do little—she lacks jurisdiction over AssetCo (which is never in bankruptcy) and thus has no authority over the assets that tort victims will recover from.

This theoretical framework of organizational law reveals what designer bankruptcy is really about, along with its potential benefits, and its potential perils. And with this theoretical framework, it becomes possible to harness organizational law to better design designer bankruptcy. That means increasing the value of a bankrupt business and, in turn, channeling that increased value to the creditors, ensuring that tort victims recover more than they do in the current designer bankruptcies.

Start with asset partitioning. Organizational law shows that asset partitioning—through corporate mitosis—will be valuable whenever the mass-tort defendant continues business operations. Likewise, keeping that operational business outside of bankruptcy’s regulatory partition adds value by easing the business’s operations.

As for bankruptcy’s regulatory partitions for tort creditors, it always makes sense to coordinate tort creditor collection efforts. That ensures tort creditors do not dismember a valuable business (limiting their overall recovery) and that early tort victims do not eat away the recovery of later ones (but rather similar injuries receive similar compensation across time). So too there is always value in establishing an administrative scheme for compensating tort victims. Such a scheme saves litigation costs, accounts for claimants over time, and ensures that compensation decisions are driven by medical expertise rather than litigation pressure.

As for governance, it is key that the tort victims’ trust has the information and motivation to protect the tort victims. That requires a duty of loyalty to those victims and a duty of impartiality among them, as is standard in trust law.[38] It also requires giving the trustee access to information on the operating business to prevent machinations that favor the business’s shareholders over its tort victims.

In turn, this theoretical understanding can be translated into policy by Congress and can provide guidance to courts superintending today’s designer bankruptcies. For Congress, the analysis of organizational law’s benefits and perils lends itself to a statutory scheme for designer bankruptcy. For courts, the analysis highlights areas of concern that require policing, like conflicted management, weak funding agreements, hidden information, and improper shareholder control of the process.

The balance of the Article proceeds as follows. Part I describes the evolution of designer bankruptcy, from Manville to the Texas Two-Step. Part II places those bankruptcies into a theoretical framework from organizational law. Part III translates that theoretical framework into suggestions for legislation and, failing that, suggestions for courts facing that designer bankruptcy.

I. The Evolution of Mass-Tort Bankruptcy

When Congress overhauled the Bankruptcy Code in 1978, it did not contemplate bankruptcy as a landing ground for mass torts.[39] Not one provision of the new Bankruptcy Code spoke specifically to mass torts. Yet lawyers discovered the use of bankruptcy for managing mass tort liabilities early on, just a few years after the Bankruptcy Code came into effect.[40] The evolution of bankruptcy as a tool for managing mass tort is thus a testament to the work of many first-rate bankruptcy professionals; it is also a cautionary tale of how tort victims can be given short shrift.

This Part tells the story of that evolution, its many benefits, and their attendant perils. It begins with the Manville innovation that started it all, and that became the touchstone for mass-tort bankruptcy. The Part then turns to Congress’s codification of that Manville Model in § 524(g), a provision of the Bankruptcy Code added to address mass-tort asbestos bankruptcies. After that, this Part looks at how mass-tort bankruptcy moved to the shadow of bankruptcy law, with prepackaged bankruptcies based on § 524(g) becoming a popular way to expedite a Manville Model bankruptcy. Last, this Part explains the Texas Two-Step, the culmination of Manville’s initial innovation, which essentially recreates the Manville Model outside of bankruptcy and is the cutting edge of today’s designer bankruptcies.

A. Manville

1. Asbestos

The evolution of mass-tort bankruptcy begins with asbestos. Thanks to its strength, flexibility, and fire resistance, the mineral quickly found use in insulation everywhere from houses to ships.[41] That pervasiveness meant that throughout the country, millions were exposed to asbestos.[42]

And exposure to asbestos can cause cancer. As early as the 1930s, reports warned of the danger.[43] A landmark study by Irving Selikoff in 1964, though, set the causal question to rest.[44]

Once it did, a deluge of lawsuits began. The earliest lawsuits were filed in the 1960s, but the floodgates truly opened in the 1970s.[45] A 1991 report from the Judicial Conference of the United States gives a sense of that deluge. In 1990, new asbestos cases were filed at a rate of 1,140 per month, constituting more than 6% of the entire civil caseload in the federal system.[46] That was on top of a backlog of 30,401 federal asbestos cases, which boded particularly ill as the average asbestos case took nearly twice as long to dispose of than the average personal injury case.[47] And estimates suggested that over 200,000 people would die of asbestos-related injuries (on top of those injured), auguring an unending stream of lawsuits.[48]

2. The Manville Plan

The turn to bankruptcy happened in 1982, when Manville, the country’s leading asbestos manufacturer, filed for bankruptcy.[49] When it filed, the business faced 16,500 suits, with 400 new ones being filed each month[50] and another 35,000 suits (with an estimated $1–2 billion in liability) projected.[51]

At the time, Manville was paying its debts as they came due, which led to some controversy around the bankruptcy filing. Many questioned how a solvent, Fortune 500 company with $2 billion in annual revenues and $2 billion in assets could legitimately file for bankruptcy.[52] And many railed against the maneuver as a delay tactic.[53] Manville responded by predicting that its future liabilities and the sheer cost of litigating would prove more than the $2 billion[54]—predictions that turned out to be truer than anyone, including Manville, appreciated at the time.

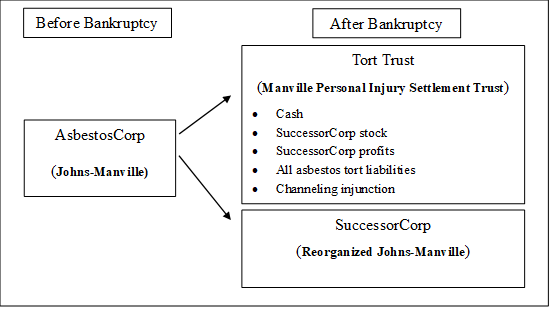

What made the Manville bankruptcy truly innovative, though, was not its filing,[55] but its Chapter 11 plan. That plan created two new legal entities from the old Manville, undertaking a form of corporate mitosis through bankruptcy law. One new entity, the Personal Injury Settlement Trust, was a trust whose beneficiaries were Manville’s tort victims.[56] The other new entity, the Property Damage Trust, was to address asbestos-related property claims.[57] Both trusts were split off from the reorganized Manville, which acted as a successor corporation to the prebankruptcy Manville and carried on Manville’s business, but without prebankruptcy asbestos liabilities.[58]

The Personal Injury Settlement Trust was funded by a combination of cash and stock in the successor Manville. Specifically, the Trust received $150 million in cash; $695 million in insurance proceeds; 80% of the common stock in reorganized Manville; a $50 million note; various long-term bonds; and 20% of Manville’s future profits.[59] All of that was to be used exclusively to pay tort victims, as the trust duties ran solely to them, not other Manville creditors.[60] Thus, the trustees would establish protocols to determine if a tort claimant was in fact injured and, if so, the proper recovery payment.

At the same time, the bankruptcy court entered a channeling injunction. That injunction required asbestos claimants to bring their claims to the Trust and only the Trust.[61] Thus, tort victims could not reach the assets of the successor corporation.

The successor corporation, then, contained all other assets and liabilities from old Manville. That meant everything besides the cash and stock in the Trust and the asbestos liabilities. Going forward, then, the creditors of the successor corporation (banks, employees, suppliers) would know that they could not reach trust assets but could reach all other assets if, for example, the successor corporation breached their contract. Likewise, they would know that asbestos victims could not reach the successor corporation’s assets. Visually, then, the Manville Model looked like this:

Figure 1

Tort victims overwhelmingly voted for this plan. Of the 52,440 asbestos claimants, 95.8% approved the plan and only 4.2% opposed it.[62] Indeed, the only class to vote against the plan was the class of stockholders whose interests were being diminished in favor of the tort claimants.[63]

3. The Follow-On Litigation

Manville’s innovation was not without controversy. Litigants challenged both Manville’s good faith (for filing when it could pay its debts)[64] and the channeling injunction,[65] which had never before been used by a bankruptcy court.

The bankruptcy court rejected the motions to dismiss for lack of good faith. In so doing, the court noted that the Bankruptcy Code does not require insolvency for a debtor to file and is instead aimed at offering relief to debtors who need to reorganize.[66] Rejecting the argument that Manville’s bankruptcy was fraudulent or a delay tactic, the court pointed out that “Manville is a real business with real creditors in pressing need of economic reorganization.”[67]

Later in the case, the court found that it had authority to issue the channeling injunction.[68] It relied both on its inherent equitable power as a bankruptcy court and the codification of that power in § 105 of the Bankruptcy Code, which authorizes the court to “issue any order, process, or judgment that is necessary or appropriate to carry out the provisions of this title.”[69]

On appeal, the Second Circuit affirmed on both issues. It addressed the good faith challenge briefly, noting that “Manville honestly believed that it was in need of reorganization and that the Plan was negotiated and proposed with the intention of accomplishing a successful reorganization.”[70] The four years of negotiations and the compounding asbestos liabilities undoubtedly helped prove the point that Manville needed reorganizing.

As for the channeling injunction, the court found that the tort claimants who challenged it lacked standing.[71] This saved the Manville plan. But it did not shore up the merits argument that bankruptcy law permits bankruptcy judges to issue such channeling injunctions.

4. Ongoing Problems

These opinions protected Manville’s plan but still left challenges for future mass-tort bankruptcies. Among them: legality, underfunding, administrative design, and future claimants.

Legality. Foremost among the challenges was legality. While the Second Circuit’s opinion saved Manville’s plan, it did so on standing grounds.[72] And the Supreme Court did not step in. That left uncertainty as to whether a channeling injunction of the sort entered in Manville’s bankruptcy could be replicated.

Without such an injunction, the Manville Model of splitting a mass-tort defendant into a tort trust and a successor corporation (SuccessorCorp) would fall apart. The tort victims would receive the trust assets and the SuccessorCorp assets (because no channeling injunction would force tort claimants into the trust alone). Meanwhile, other creditors would receive only SuccessorCorp assets (because the trust runs for the benefit of tort victims alone).

Underfunding. As for underfunding, when the Manville Personal Injury Settlement Trust was established, the funding was based on estimated asbestos liabilities. Those estimates were that 83,000 to 100,000 claimants would file with the Trust and that the dollar value of those claims would be in the ballpark of $1 billion.[73] That estimate proved astonishingly off. By the spring of 1990, the Trust had received 150,000 claims and was already insolvent.[74] A special master’s report found that the assets remaining had a value between $2–3 billion, while liabilities were around $6.5 billion.[75]

In response, largely through the efforts of Judge Jack Weinstein, the Trust distributions were redesigned.[76] Under the new Trust Distribution Plan, asbestos diseases were categorized and assigned payout values.[77] Claimants would then be entitled to a pro rata share of that value, set at 10%.[78] Were they dissatisfied, they could arbitrate with the Trust, and failing that, they could sue.[79] In essence, then, while tort claimants retained their right to a jury trial,[80] the trustees established a system for administering claims.[81]

Nor was the underfunding issue unique to Manville. The early tort trusts all struggled to repay claimants.[82] And some, like National Gypsum Company’s, also required a re-funding, as Manville’s did.[83]

Administration. That distribution plan mirrored a workers’ compensation scheme.[84] Essentially, the trustees established a grid that listed asbestos injuries that victims might have and dollar values for payouts. To do that, though, required the trust to draw on expertise in multiple fields. For one, it needed medical expertise to understand causation and harms of asbestos.[85] Beyond that, it needed financial expertise to manage assets in the trust. And it needed lawyers to settle, negotiate, and often litigate claims, often leading to the very same litigation expenses that drove the businesses into bankruptcy to begin with.[86]

Over time, Manville Model bankruptcies improved on each of these fronts. A better understanding of asbestos harms led to more granular compensation grids.[87] And trusts shifted away from a litigation-centric model, preserving the right to a jury trial but requiring negotiation first so that claimants could not use litigation pressure to jump the settlement line or extract value simply by imposing litigation costs on the trust.[88]

Future Claimants. A final issue that arose was that of future claimants. Asbestos has a long latency period, so many injured by Manville would not see their cancer manifest for decades. The Trust, by its terms, benefitted those future claimants as well. And early in the case, Judge Lifland appointed a legal representative to protect their interests.[89]

But estimating future injuries and preserving value enough in the Trust is a taller task than estimating current injuries—something that the Manville Trust, as described above, failed to do.[90] And nothing in the Bankruptcy Code ensured protection for future claimants in the process of negotiating a plan—it was Judge Lifland’s decision alone that protected them, a decision that might not be replicated in other mass-tort bankruptcies.

This protection for future claimants would become a recurring theme. Those claimants, by definition, were not negotiating Manville’s Chapter 11 plan. So they ran the risk of present victims taking all of the assets. That absence from the bargaining process compounded the mathematical challenge of determining the right dollar value to be preserved for future claimants over and against the value to be distributed immediately to present claimants.

B. The Statutory Manville Model

1. Section 524(g)

In the wake of the Manville bankruptcy, Congress saw an opportunity. Manville’s innovation succeeded in reorganizing a massive asbestos-laden business. And there were other businesses (and the entire civil litigation system) struggling with tens of thousands of asbestos claims.[91]

Codifying Manville. So, in 1994, Congress added § 524(g) to the Bankruptcy Code. The section mirrored Manville’s innovation[92] and thus had the benefit of making Manville Model reorganizations clearly legal for asbestos bankruptcies.[93] It also retroactively blessed Manville and other asbestos bankruptcies that had relied on a channeling injunction.[94] By resolving that uncertainty for past Manville Model bankruptcies and authorizing the Manville Model going forward, Congress removed a weight from the shoulders of reorganizing asbestos businesses, paving the way for smoother asbestos bankruptcies that served both the business (which could operate without the looming tort claims) and the tort victims (who received the extra value of the business’s smooth operation).[95]

To codify the Manville Model, § 524(g) explicitly authorizes bankruptcy courts to enter channeling injunctions[96] and third-party releases[97] in connection with a plan that resolved asbestos liabilities by creating a trust. The section was limited to bankruptcies based on asbestos liabilities and in which a trust would contain personal-injury actions based on those liabilities.[98]

Addressing Futures Claims. Congress also provided more precision for protecting future claims. For one, the statute requires a court to find that future claims would be paid “in substantially the same manner” as present claims before approving a § 524(g) plan.[99] That prevents present claimants from consuming all of the assets. So too Congress provides for a legal representative for future claimants, though the statute does little beyond that to flesh out the role.[100]

Protecting Tort Victims. In the same vein, Congress requires a supermajority vote of tort claimants—75%—to ensure the plan in fact serves them.[101] So too Congress requires that the plan give tort claimants stock in the reorganized SuccessorCorp.[102] Both of those mechanisms ensure that tort victims would not be given short shrift in the plan and that they would themselves benefit from the value added by the reorganization.

Outcomes. Section 524(g) proved popular and effective. During the decade after its passage, forty-four asbestos bankruptcies relied on the section to effect a reorganization.[103] By 2018, that number was 120.[104] And by 2011, some $36.8 billion were held in tort trusts for the benefit of tort victims.[105] What resulted were bankruptcies that preserved more value of SuccessorCorps and, in so doing, assured further payment for tort victims.[106]

2. Ongoing Problems

Section 524(g) did much good. It enshrined the legality of Manville Model tort trusts, afforded heightened protections to tort victims, and formalized representation for future claimants. At the same time, it left various problems festering in mass-tort bankruptcy.

To begin, the section is, by its terms, limited to asbestos bankruptcies.[107] That makes sense given asbestos’s latency period, the need for future claims representation, and the distinct economic challenge that was fore of mind in 1994. But it also precludes the benefits of such bankruptcy for mass torts that could use them, like Dow Corning Corporation’s bankruptcy, which owed to mass-tort liability related to its silicone breast implants.[108]

So too § 524(g) did little to speed up the bankruptcy process. Writing in 2003, Francis McGovern—who held a court-appointed position in many of the major § 524(g) cases—wrote that the typical plan took four to six years to confirm.[109] All the while, the business remains in limbo and value slips away.[110]

And once a plan is confirmed, § 524(g) has little to add on administration. Indeed, the section protects against underfunding only nominally, requiring a judge to find “reasonable assurance” that the tort trust will be able to pay future claims in “substantially the same manner” as comparable present claims.[111] It is silent on the administration, leaving the trust to its own devices when it comes to classifying injuries, finding experts, determining the payouts, and the like. Nor does the section speak to multiple recoveries, which led to some tort victims’ double-dipping, that is, recovering from multiple asbestos trusts for their injuries and, in turn, depriving other tort victims of a full recovery.[112]

C. Prepackaged Manville Models

1. The Rise of Asbestos Prepacks

With § 524(g) in place, bankruptcy lawyers went about designing asbestos bankruptcies before filing them. That meant negotiating with creditors, reaching a plan, soliciting votes on that plan, and only then filing for bankruptcy. Essentially, this strategy of “prepackaged” asbestos bankruptcy amounted to doing the work of bankruptcy beforehand and filing only to receive the bankruptcy court’s stamp of approval for any restructuring matters that required it.

And though these prepackaged bankruptcies would seem to have things backward, the Bankruptcy Code itself does contemplate them. Section 1121(a) allows the debtor to “file a plan with a petition commencing a voluntary case[.]”[113] So too §§ 1125(g) and 1126(b) permit the debtor to solicit votes on that plan before filing.[114] All these sections were written with prepackaged bankruptcy in mind.[115]

Nor were asbestos debtors the only ones to take advantage of the ability to prepackage their bankruptcies. Throughout the 1990s, debtors in all industries took advantage of the prepackaged route—by 2009, around one-third of bankruptcies each year were either prepackaged or prearranged (negotiated in advance but without a vote).[116]

Its main benefit: speed. A typical prepackaged bankruptcy takes a few months,[117] and some are as quick as one day.[118] And the asbestos cases were no different, registering only a handful of months in bankruptcy before a plan could be confirmed.[119] That, in turn, saves significant costs from the bankruptcy proceeding itself.

2. Ongoing Problems

At the same time, the speed of prepackaged asbestos bankruptcy brought some risks for tort victims, largely due to the lack of court oversight of the negotiation process. Among these were the issues of future claimants, lawyers’ incentives, and the defendants’ interest in settling for as little as possible.

In a § 524(g) bankruptcy, there must be a future claims representative.[120] But in a prepackaged bankruptcy, the court has no involvement in or oversight of the negotiations. As a result, the debtor-to-be hires a future claims representative and then negotiates with that very representative. That dynamic lends itself to a future claims representative failing to adequately bargain for the claimants she represents.[121]

A similar issue arises from the negotiations with plaintiffs’ lawyers who represent the current claims. Because negotiations take place outside of the bankruptcy court, lawyers with large inventories of claims can shape the negotiation.[122] That comes at the expense of the tort victims represented by other lawyers and, especially, those future tort victims who are not represented (or are represented nominally by the future claims representative).

This negotiating dynamic is worsened by the debtor’s interest in paying as little as possible. That means the debtor has every reason to underfund the tort victims’ trust and to buy off the major plaintiffs’ lawyers with a handsome fee to do so.[123] So too it gives the debtor every reason to hire a pliable future claims representative. And that is all true even when the business is insolvent and therefore may consider the interests of creditors and not just shareholders.[124]

The lack of court oversight compounds these challenges. By the time negotiations have concluded, votes have been cast, and a petition has been filed, the bankruptcy judge faces significant pressure. The overwhelming consensus at that point favors the plan, however poor it is, and that creates a sense of inevitability. The judge also has little window into the assets, the appropriate amount of funding, and the negotiation process itself. That can potentially create a world where a misbegotten bankruptcy process shortchanges tort victims and the judge has little ability to nix the deal.

These pathologies were on display in high-profile prepackaged cases. Take, for example, the J.T. Thorpe bankruptcy.

Thorpe filed a prepackaged § 524(g) bankruptcy on October 1, 2002, and had judicial approval for its plan by December 18, 2002.[125] To achieve that plan, though, Thorpe negotiated with some of the plaintiffs’ attorneys in advance of the filing.[126] No future claims representative was appointed until the bulk of Thorpe’s assets had already been placed in trusts for the major plaintiffs’ attorneys’ clients.[127] The result was a plan that favored present tort victims over future tort victims and those represented by lawyers with large inventories of claims over those represented by smaller outfits.[128]

Nor was Thorpe unique. In both In re Combustion Engineering, Inc.[129] and In re Congoleum Corp.,[130] the debtor paid a “success fee” to high-profile plaintiffs’ attorneys, who represented many claimants, to reach a global settlement.[131] That likewise led to the debtor and the attorneys trading off future-claimant interests (along with present claimants represented by other lawyers) for their clients’ interests. So too in In re ACandS, Inc., [132] where the judge denied plan confirmation, noting that the plan “was largely drafted by and for the benefit of the prepetition committee” and “[n]ot only . . . discriminate[s] between present and future claims, it pays similar claims in a totally disparate manner.”[133] Thus, while the era of prepackaged asbestos bankruptcy did achieve the benefits of speed, to add to the benefits of the original Manville Model, it brought new downsides because of the negotiating dynamic and minimal court oversight.

D. The Texas Two-Step

The latest development in designer bankruptcy, the Texas Two-Step, pushes the prepackaged Manville Models one step further, recreating the same corporate mitosis outside of bankruptcy. In the Two-Step, a mass-tort defendant splits off its liabilities into a special-purpose entity and has the newly formed legal entity file for bankruptcy.[134] Meanwhile, the rest of the business remains outside of bankruptcy the entire time.

1. The Legal Maneuver

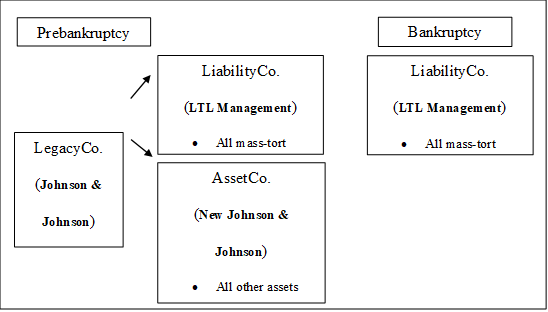

Conceptually, then, the Two-Step shifts a Manville-style maneuver before bankruptcy, leaving the SuccessorCorp outside of bankruptcy altogether. From a legal perspective, this is how the Two-Step is constructed. Start with a legacy company (LegacyCo) (the equivalent of AsbestosCorp[135] in the Manville Model) that incurs mass-tort liability and has various business assets corresponding to those liabilities.

The first step for LegacyCo is to conduct a divisional merger, typically under Texas law. That divisional merger allows a business organization to divide in two, allocating assets and liabilities as it pleases across the two new entities.[136] LegacyCo uses the divisional merger to allocate all mass-tort liabilities into the newly formed LiabilityCo and everything else (ordinary business liabilities and all assets) into AssetCo.

Figure 2

To ensure that the maneuver does not run afoul of either Texas[137] or federal fraudulent transfer law,[138] the two new companies will enter into a funding agreement, which promises that AssetCo will pay LiabilityCo such amounts as a court requires under bankruptcy law.[139] LiabilityCo and AssetCo, through the funding agreement, will also indemnify one another.[140] After that, LiabilityCo will file for bankruptcy. And AssetCo will carry on the same business operations of the now-defunct LegacyCo.

The result of these maneuvers is similar to the Manville Model. For starters, the automatic stay in bankruptcy prevents tort creditors from suing LiabilityCo.[141] But a court will also enter an injunction against tort creditors suing AssetCo because the indemnification agreement means that any suit against AssetCo will be paid by LiabilityCo and thus diminishes the assets available to LiabilityCo in its bankruptcy.[142] Together, these provisions operate as a channeling injunction, forcing tort claimants to go to the bankruptcy court and recover from LiabilityCo alone. Conversely, regular business creditors of AssetCo will avoid LiabilityCo altogether as their debts (and assets backing them) remain inside AssetCo, which itself remains outside of bankruptcy.

2. Improvements on the Manville Model

The Two-Step adds to many of the advantages of the Manville Model. Beyond the benefit of keeping productive assets in a distinct SuccessorCorp that can operate normally (without tort creditor interference), the Two-Step ensures that operational assets never enter bankruptcy to begin with.[143] So those assets remain beyond the interference of the creditors and beyond the burdens imposed by bankruptcy law.

In turn, that reduces the costs of operating AssetCo, saving money for the tort victims, which they receive through the funding agreement. Likewise, the bankruptcy of LiabilityCo itself becomes less costly because there is little to wrangle about for the reorganization—LiabilityCo does not operate a business and thus the bankruptcy does not drag on for years negotiating over that reorganization.

Also, unlike a prepackaged § 524(g) bankruptcy, there are no skewed negotiations.[144] The funding agreement specifies that AssetCo will pay the full value to which bankruptcy entitles tort victims in LiabilityCo’s bankruptcy.[145] So select plaintiffs’ lawyers cannot cut a favorable deal with AssetCo and freeze out either future claimants or present claimants who picked the wrong lawyers. In fact, the future claims representative will be appointed by the court and will be present for the entirety of negotiations—all of which happen inside the bankruptcy, unlike in a prepackaged bankruptcy.[146]

Finally, the Two-Step need not be limited to asbestos. While the major cases so far have involved suits against companies for asbestos—DBMP, Bestwall[147]—nothing about the maneuver requires as much. Indeed, 3M initiated a copycat maneuver, relying on the same mutual indemnification strategy to create a Two-Step to manage Aearo’s liability for earplugs made for the military.[148]

3. Ongoing Problems

At the same time, the Two-Step poses risks that attend all its benefits. These risks are tied directly to its ability to keep assets outside of bankruptcy altogether.

Underfunding. For starters, there is the risk of an inadequate funding agreement. In a Manville Model bankruptcy, the assets of the business are all in bankruptcy, at least for some amount of time.[149] But in a Two-Step, there is a risk that LegacyCo uses the maneuver to hide assets from tort victims. For example, if tort victims are owed $2 billion and the funding agreement caps their recovery at $1 billion while leaving another $4 billion of LegacyCo’s assets in AssetCo, the bankruptcy gives tort victims less than they are entitled to under bankruptcy law.[150]

That extreme example is unlikely, but more subtle versions abound. Suppose the funding agreement entitles tort victims to every penny that a LegacyCo bankruptcy would yield for them. But now suppose that management of AssetCo decide to issue a dividend. Those dividends might underfund AssetCo to the point that it cannot pay all that the tort claimants are owed. To extend the previous example, the funding agreement might allot tort claimants the $2 billion they are owed, but AssetCo pushes out $4 billion in dividends, leaving only $1 billion in AssetCo. That effectively pays shareholders instead of tort victims, violating the absolute priority rule that would prevail in a LegacyCo bankruptcy.[151]

More subtle still, AssetCo might simply undertake risky projects, a typical form of the traditional debt-equity conflict. To borrow an example from Laura Lin:[152] Imagine a business with $8,000 in assets and $10,000 in liabilities. It can undertake one of two projects. The first will result in a value of $8,500 for the business. The second will, with 10% probability, result in a value of $50,000 for the business and, with 90% probability, result in a value of $200 for the business. The first project has a higher expected value ($8,500 versus $5,180). But shareholders will prefer the second because they receive no payment if the first project is undertaken, and they have the possibility of a payout if the second project is undertaken.[153]

Ordinarily, contract creditors use covenants to prevent such maneuvers.[154] In a Manville bankruptcy, the tort claimants themselves own stock, also mitigating the conflict. But here, the tort claimants own no stock in AssetCo (and never will).[155] So management in AssetCo might undertake projects that are poor bets and might result in AssetCo lacking the assets to back the funding agreement (even if, when LiabilityCo entered bankruptcy, AssetCo had enough assets to pay it).

Loyalty. Worse yet, management are unlikely to protect tort victims. For starters, management of AssetCo owe a duty to their shareholders. In cases of uncertain solvency, AssetCo management may consider creditors but need not do so.[156] And even if AssetCo is insolvent, creditors will have a difficult time challenging management’s decisions given the business judgment rule.[157]

LiabilityCo’s management will all be installed by LegacyCo in the divisional merger. That means their loyalties will lie with shareholders of LegacyCo. By way of example, in Johnson & Johnson’s Two-Step, the management of LiabilityCo are seconded from the parent corporation and thus, quite literally, are on Johnson & Johnson’s payroll.[158]

The result is that management might decline to pursue a fraudulent transfer action. They might also settle a fraudulent transfer action on the cheap, especially in more subtle cases, like a dividend, where management can plausibly argue that the dividend did not render AssetCo insolvent and thus that LiabilityCo is unlikely to prevail in litigation.[159] And because the debtor’s management control such fraudulent-transfer claims, tort victims will not be able to bring those cases on their own if management fall short.[160]

Delay. All that makes the Two-Step an excellent delay tactic for mass-tort defendants. Because management, not tort victims, control the proceeding, and management can delay negotiations, refuse to bring fraudulent-transfer suits, and the like, tort victims are in a bind.[161] They often need cash imminently for medical expenses yet have no ability to sue (the automatic stay and third-party injunction bar that). And because the funding agreement conditions payment on the victims voting to confirm a plan, victims have no way to obtain payment during the pendency of the bankruptcy.[162]

Legality. Finally, the legality of the Two-Step is not entirely clear. In particular, the Two-Step relies on the court in LiabilityCo’s bankruptcy entering a third-party release for AssetCo. This repeats the issue of the channeling injunction in Manville, where scholars, lawyers, and judges debated whether bankruptcy courts can lawfully order such a release.[163] Congress resolved that issue for asbestos cases in § 524(g).[164] But for other mass torts, courts across the country are split on both the legality of such releases and the standard to apply.[165]

The maneuver itself (apart from third-party releases) has also had a mixed run in court. Bankruptcy judges in the Fourth Circuit, where Two-Step cases tend to be filed,[166] have all refused to dismiss the bankruptcies.[167] But the Third Circuit, in In re LTL Management, LLC,[168] imposed a financial-distress requirement before mass-tort defendants can use the Two-Step, dismissing Johnson & Johnson’s case.[169] Two-Steppers will either satisfy that requirement by claiming such financial distress (often legitimately, given the amount of liability looming in mass torts) or avoid it by continuing to forum shop to jurisdictions that do not impose a financial distress requirement. The result will be a combination of forum shopping[170] and uncertain legality in large, mass-tort bankruptcies.

All in all, then, the Texas Two-Step amplifies both the benefits and risks of the Manville Model. By moving the corporate mitosis before bankruptcy, the Two-Step makes business easier and preserves more value than would be lost in bankruptcy. At the same time, it also poses risks to tort victims because of the lack of oversight created by the shift to prebankruptcy mitosis.

II. A Theoretical Framework: Organizational Law, Bankruptcy Law, and Mass Torts

The designer bankruptcies described above all rely on the interaction of corporate structure and bankruptcy law. In doing so, they get at bankruptcy’s most fundamental questions—which assets and liabilities are contained in which legal entities, which of those entities are subject to bankruptcy’s legal regime, and how those entities are governed.

Each of these questions is known from organizational law, which explores the law surrounding legal entities like corporations, trusts, and other legal persons. Respectively, these are the questions of asset partitions, regulatory partitions, and governance. This Part places the iterations of mass-tort bankruptcy—the Manville Model and the Texas Two-Step—into an organizational law framework. In so doing, it shows how the benefits and dangers of each framework fit into well-understood categories and points the way to understanding how bankruptcy can offer the best of both worlds: maximizing the value of the mass-tort business and ensuring that tort victims receive every penny bankruptcy law entitles them to.[171]

A. Asset Partitioning

1. The Fundamentals of Asset Partitions

The essential role of a legal entity is asset partitioning, that is, defining which assets belong to the entity and which to its owners.[172] That partition, in turn, defines which assets creditors of the entity (or the owners) can access.

The simplicity of those asset partitions belies their importance. By defining assets of a legal entity, creditors of that entity can know which assets to monitor and which assets they can recover if the entity does not, for example, perform its contracts. And those benefits can be directly tied to the rise of the modern firm.[173]

To take the classic example, imagine a business that operates both a chain of hotels and an oil refinery.[174] The business can either keep both lines of business in one corporation or it can incorporate the hotel business and the refinery separately. Typically, it makes sense to incorporate separately because the businesses rely on different creditors. The hotel business creditors know little about oil refineries. So it is easy for them to monitor the hotel business and understand the likely fortunes of the hotel business. Not so for the refinery, though, where hotel creditors have little knowledge. Hence, separately incorporating the two businesses relieves the hotel creditors of worrying about the oil business and, in turn, allows those creditors to extend credit to the hotel business on better terms.[175]

Another key benefit of asset partitioning lies in its ability to cure a debt overhang. Businesses with high debt (like mass-tort debt) often struggle to raise capital, even for valuable projects. To borrow an example from Mark Roe, imagine a firm worth $2 billion but owing $5 billion in future debt.[176] Equity financing is unattractive because stockholders recover after creditors, meaning that new stockholders’ money will likely end up in the hands of preexisting creditors.[177] Likewise, new unsecured creditors will worry that their loans will be used to pay preexisting claims and, thus the new investment will not be repaid.[178]

Yet creating a new corporation can solve this problem. A new corporation will have no debt when formed, and thus new equity and new credit need not worry about the preexisting debt of a parent business.[179]

These benefits of asset partitioning—lowering monitoring costs and curing debt overhang—give potential creditors reasons to lend to a business that takes advantage of asset partitioning. In turn, that facilitates investment, which has led to the rise of modern, large-scale business enterprises.[180]

2. Designer Bankruptcy as Asset Partitioning

All of the iterations of designer bankruptcies undertake some form of asset partitioning. The Manville bankruptcy, for example, created a successor corporation whose assets could not be reached by asbestos creditors but were available to other creditors, like employees, lenders, and suppliers.[181] At the same time, the Manville Trust’s beneficiaries were tort victims and thus the assets of the Trust could only be accessed by those tort victims.[182] Therefore, the Manville Model partitions asbestos liabilities and assets to compensate victims into one pool (tort trust) and the remaining liabilities and the business’s operational assets into another pool (SuccessorCorp).[183]

The § 524(g) and prepackaged bankruptcies that followed did the same, as they are statutory versions of the same Manville Model. In both, a SuccessorCorp and a tort trust are created through the process of bankruptcy.[184] The trust’s beneficiaries are the tort victims, for whom a pool of assets is partitioned.[185] And the channeling injunction ensures that the tort victims can access only the assets of the trust—not the successor corporation. That leaves other creditors with a defined pool of assets, namely, the successor corporation (and not the trust), that they alone (and not tort creditors) can reach.

So too the Texas Two-Step partitions assets. Tort victims, and only tort victims, may access the asset that is the funding agreement.[186] That is so because the tort creditors are creditors of LiabilityCo and LiabilityCo alone benefits from the funding agreement. Conversely, tort creditors may not reach the assets of AssetCo thanks to the bankruptcy court’s injunction. Those assets, instead, may be accessed by AssetCo’s creditors and only them. In short, then, the Two-Step partitions the funding agreement and tort liability into one asset pool (LiabilityCo) and the remaining assets and liabilities into another asset pool (AssetCo).

Key, though, is that the Texas Two-Step’s asset partitioning is incomplete. That’s so because the pools overlap—the funding agreement draws on the assets in AssetCo.[187] So business creditors of AssetCo can dip into the assets that back the funding agreement, meaning that the defined pool of assets for tort creditors (the funding agreement) is not exclusively available to tort creditors.[188] Nor do they even have priority on those assets over business creditors of AssetCo as the tort judgment and the funding agreement create no security interest.[189] Conversely, the funding agreement allocates a certain amount of AssetCo assets to the tort creditors’ LiabilityCo, and thus business creditors only have some assets of AssetCo that are defined exclusively for them.[190]

All this holds until the end of the bankruptcy. At that point, a plan will define the assets for LiabilityCo and for AssetCo, presumably requiring that the plan for LiabilityCo result in hard assets to be distributed to victims.[191] Once that happens, complete asset partitioning would be achieved and overlapping claims on the same assets would be eliminated.

3. Benefits of Bankruptcy’s Asset Partitioning

In principle, this bankruptcy form of asset partitioning promises the same benefits as ordinary asset partitioning. This is true for a Manville Model in all situations and for a Texas Two-Step that confirms a plan in which the funding agreement is replaced by assets placed in AssetCo, thus achieving a complete asset partition.

Take the example of Manville’s partition. Would-be creditors of SuccessorCorp need not concern themselves with the business’s tort liability and can instead invest based on the value of the assets, monitor those assets, and be confident about which assets they can recover should the business fail. That results in lower monitoring costs, as traditional asset partitioning yields. And it can cure the debt overhang caused by tort liability, just as traditional asset partitioning can.

Likewise, tort victims have certainty. The tort victims know that only they will have access to the tort trust assets. So they need not fret that the cash in the trust will be used to pay non-tort creditors.[192]

All in all, then, designer bankruptcy’s asset partition cures a debt overhang through the Manville Model or a properly designed Two-Step plan. Both also reduce the monitoring costs for non-tort creditors who interact with SuccessorCorp or AssetCo. And both limit the monitoring costs for tort creditors, who no longer need to worry about the business operations of SuccessorCorp or AssetCo.

And by curing the debt overhang, either designer-bankruptcy maneuver yields extra investment in SuccessorCorp or AssetCo that benefits the tort victims. Because a Manville trust includes stock in the successor corporation, an increase in the value of the successor corporation increases the assets available for tort victims to recover.[193] Likewise, for a Texas Two-Step the funding agreement allocates increased value of AssetCo to the tort victims.[194] So the benefits of the asset partition (monitoring, curing debt overhang) accrue to the benefit of both the business and the tort victims.

4. The Role of Bankruptcy

What is the role of bankruptcy in all this? After all, these maneuvers are not primarily bankruptcy maneuvers. Asset partitioning does not rely on eliminating prior debt (bankruptcy’s discharge) or restructuring business operations under court supervision (bankruptcy’s reorganization plan). The maneuvers reshuffle assets and liabilities, using bankruptcy’s stay and injunctions to do so instead of corporate law. The answer: Bankruptcy’s traditional roles make it well-equipped to do both ex ante and ex post partitioning.

Ordinary asset partitioning happens ex ante through corporate law. The corporation sets up a subsidiary for the hotel and a separate subsidiary for the refinery before investors decide to invest.[195] Indeed, that is how the business captures the benefits of asset partitioning—saving hotel creditors the costs of monitoring the refinery and vice versa.

But ex post asset partitions do not really work, at least in cases of insolvency. Once the corporation has incurred liability, it cannot simply invalidate the liability. Nor can it move assets to avoid paying that liability; fraudulent transfer law undercuts such maneuvers.[196] By way of example, if the business initially houses the hotel and the refinery in the same corporate entity and then the hotel business flops, the corporation cannot then incorporate the refinery and hotel separately, leaving the hotel insolvent while the refinery continues to turn a profit with assets that once belonged to the legacy corporation.[197] Even if the spinoff involved a funding agreement, hotel creditors would (at least indirectly) have access to the same pool of assets as the refinery creditors, undercutting any asset partition.[198]

But bankruptcy law is well-equipped to conduct that asset partitioning. Bankruptcy always acts ex post (the liability has been incurred), and it always defines which creditors receive which assets. Bankruptcy, by design, addresses competing claims to the same assets and thus determines who owns assets.[199] That requires it to have certain tools: a stay[200] to prevent creditors who are not entitled to assets from obtaining them; injunctions[201] to prevent creditors who are not stayed from obtaining assets they are not entitled to; a discharge[202] to prevent creditors from obtaining post-bankruptcy assets that they are not entitled to; and the ability to redefine property rights through a plan of reorganization.

Together, these tools are not typically used for asset partitioning. A Chapter 11 plan typically reorganizes one business and reconfigures property rights to its pool of assets rather than creating multiple pools of assets.[203]

But those same tools are also well-suited for asset partitioning. Between the automatic stay, third-party injunctions, channeling injunctions, and a discharge, bankruptcy can ensure that tort victims cannot access the successor corporation’s assets or AssetCo’s assets while business creditors can. Conversely, those tools, along with a § 524(g) trust, can ensure that business creditors cannot access the tort victims’ assets.[204]

At the same time, that ex post asset partition is also an ex ante partition for the successor corporation. That successor corporation (or AssetCo) will continue to operate and need lenders, employees, and vendors. All of those will be more willing to extend future credit once the trust or LiabilityCo exists and the asset pools of the two legal entities (SuccessorCorp and tort trust or AssetCo and LiabilityCo) are clearly defined.

So bankruptcy proves an able mechanism for achieving asset partitioning ex post when it would be impossible through other legal mechanisms. And that is true even though such asset partitioning is not the core role of bankruptcy law.

B. Regulatory Partitioning

1. The Fundamentals of Regulatory Partitioning

The second organizational-law aspect of these designer bankruptcies is regulatory partitioning, that is, keeping assets and liabilities in separate legal entities based on legal statuses attributed to those entities and, in turn, the legal regimes that regulate them.[205]

So, for example, a corporation might choose to use a separate legal entity to transform its corporate citizenship and thus obtain the benefits of investment treaties. That was the case of Tokios Tokelés UAB, a company owned by Ukrainians but incorporated in Lithuania, which used its Lithuanian corporate citizenship to invoke arbitration under the Lithuania–Ukraine bilateral investment treaty (instead of suing in Ukrainian courts, as would be standard for such a dispute).[206] More commonly, businesses operate through separate legal entities to limit the burdens of tax law.[207] In either case, though, the legal entity benefits from opting into a particular regulatory scheme (bilateral investment treaty protections) or opting out of a regulatory scheme (a more expensive tax bill).

2. Designer Bankruptcy as Regulatory Partitioning

For designer bankruptcy, the primary regulatory partition is the bankruptcy partition—that is, which entities are subject to bankruptcy’s regulatory regime and which are not.[208] Secondarily, there is a regulatory partition in the form of imposing a workers’ compensation-style scheme for a particular mass tort.

Start with the bankruptcy partition. On the inside of the bankruptcy partition are creditors, both in the Manville Model and the Texas Two-Step. That is key because bankruptcy forces creditors into a collective debt-collection proceeding. Thus, creditors cannot dismember a viable business and will not be compensated on a first-come, first-served basis that beggars victims with latent injuries.

As for the business’s regulatory partition, bankruptcy’s regulatory regime imposes significant burdens, so businesses in bankruptcy face these regulatory burdens and those outside of bankruptcy do not.

Taking advantage of this inside-versus-outside of bankruptcy partition is a distinct development of the Texas Two-Step. In the Manville bankruptcy, a § 524(g) bankruptcy, or a prepackaged bankruptcy, the entire business enters bankruptcy and is subject to bankruptcy’s rules. Only later do two entities emerge. There is no division of legal entities in which one is subject to bankruptcy’s regulatory regime and another is not. And though the prepackaged version limits time in bankruptcy, it still subjects the entire business to bankruptcy’s regulatory regime.

But in the Two-Step, the business takes full advantage of the bankruptcy partition. AssetCo never enters bankruptcy and is thus not subject to bankruptcy’s regulatory regime.[209] LiabilityCo does enter bankruptcy and thus is subject to bankruptcy’s regulatory regime.[210] That achieves the regulatory partitioning common in other areas of business law, just as when one subsidiary of a corporation can avoid onerous tax laws.

As for the regulatory partition for compensation regimes, bankruptcy allows for mass torts to be addressed through a workers’ compensation scheme. That happens through the creation of a new legal entity in the bankruptcy court that can be made subject to such a compensation scheme thanks to bankruptcy law. In the Manville Model, for example, the court creates a trust, and tort claimants must submit a claim to that legal entity, which operates based on a workers’ compensation model imposed by the bankruptcy court.[211]

This same partitioning can be achieved in the Texas Two-Step, though we have yet to see it there. In principle, LiabilityCo can create or become a trust. And with bankruptcy court approval, the trust can impose the same type of workers’ compensation scheme that a Manville trust has.

3. Benefits of Bankruptcy’s Regulatory Partition

In principle, the Two-Step’s regulatory partition holds much promise. And this promise builds on the benefits that all forms of designer bankruptcy obtain from asset partitioning.

Inside the Bankruptcy Partition. Here’s why. A business facing a creditor run benefits from bankruptcy’s ability to coordinate creditor collection. It does so through the automatic stay and rules that determine, in an orderly fashion, which creditors receive what.[212] That prevents creditors from dismembering a valuable business, preserving value for business and creditors alike. So there is a benefit to having the creditors subject to a bankruptcy regime, which both the Manville Model and the Texas Two-Step achieve.

Outside the Bankruptcy Partition. On the flipside, a business facing that creditor run (or any form of financial distress) needs to reorganize. But it need not do so in bankruptcy. Out-of-court reorganizations are common.[213] And they are often preferable. Indeed, any distressed business could file for bankruptcy, but many use out-of-court workouts, suggesting that bankruptcy is a second-best mechanism for resolving financial distress. Largely, that owes to the out-of-court reorganization avoiding many of the costs of bankruptcy, monetary and otherwise.[214]

On the monetary side, bankruptcy requires a host of professionals. And those lawyers, consultants, turnaround specialists, and more all take their fees. Lynn LoPucki and Joseph Doherty found that in large bankruptcies (over $100 million in 1980 dollars), professional fees average 1.4% of the debtor’s assets.[215] Stephen Lubben, looking at twenty-two large bankruptcies from 1994, found that these costs totaled 2.5% for traditional bankruptcies (and less for prepackaged bankruptcies).[216]

And that just accounts for the debtor’s costs. As Anthony Casey and Joshua Macey point out, a Johnson & Johnson bankruptcy would sweep in hundreds of subsidiaries with creditors of each having to file a claim and the judge needing to value the claim.[217] And each of those creditors would incur legal costs as well—costs not captured in the classic studies on professional fees.

From the perspective of running a business, bankruptcy adds other burdens. Professional fees must be approved by the court,[218] which takes time and may deter certain professionals from working for the debtor. Transactions beyond the ordinary course likewise require court approval.[219] Creditors can, and do, object to business decisions—including key decisions like obtaining debtor-in-possession (DIP) financing so that the business has enough cash on hand.[220]

Compensation Partition. As for the workers’ compensation scheme, it has much to commend it. Outside of such a scheme, tort claimants jump to litigation. In turn, compensation turns as much on litigation pressure as anything else. But with a workers’ compensation scheme imposed through a trust, the story is different: Claimants must go to the trust first and thus cannot use pressure from their lawsuits to drive a settlement.[221] Instead, the trust draws on medical expertise to propose a compensation amount, while ultimately preserving Seventh Amendment rights if settlement negotiations break down.[222] The result is fewer litigation costs, more expertise in decision-making, and more consistency across victims.[223]

So, by coordinating creditor collection in bankruptcy and by subjecting tort claimants to a workers’ compensation scheme, designer bankruptcy (either Manville or Two-Step) has much to offer. Further, by maintaining the productive assets of the business outside of bankruptcy, the Two-Step promises AssetCo a smoother set of business operations and saves bankruptcy costs, all of which accrues to the benefit of the tort victims in the form of more value to be distributed to them.

4. The Role of Bankruptcy

As with asset partitions, much of the value of regulatory partitioning in bankruptcy has little to do with bankruptcy law or bankruptcy problems. Yet here too bankruptcy law acts as a convenient tool for achieving those partitions. And it may be the only such tool.

The one area in which these regulatory partitions invoke a traditional bankruptcy tool to solve a traditional bankruptcy problem is creditor collection. At its heart, bankruptcy is debt-collection law and aims to prevent creditors from dismembering a business with going-concern value.[224] Bankruptcy does this by subjecting creditors to an automatic stay and forcing them into the bankruptcy court to orderly manage the process of distributing the debtor’s value.

But the flipside—as seen in the Two-Step—is keeping the business operations themselves outside of bankruptcy to avoid bankruptcy’s regulatory regime for debtors. This avoidance is decidedly not about using bankruptcy law and thus bankruptcy law plays no role in this regulatory partitioning effort.

Finally, consider the workers’ compensation scheme imposed in a Manville trust. Such a scheme has nothing to do with traditional bankruptcy law or solving traditional bankruptcy problems. Indeed, the idea of such schemes originates in workplace accidents that can be more efficiently addressed with a regime of workers’ compensation than one-off tort litigation.[225] None of that has to do with solvency challenges, reorganizing businesses, liquidity crunches, or any other traditional bankruptcy concern. Indeed, such regimes can be (and usually are) imposed by a separate statute that has no connection to insolvency law whatsoever.[226]

But here, as with asset partitioning, bankruptcy has convenient tools for achieving the benefits of such a compensation scheme. In particular, the flexibility granted to plans of reorganization and the ability to channel claimants into the trust make possible this ex post creation of a workers’ compensation scheme.

And imposing such a scheme is impossible for a mass-tort defendant outside of bankruptcy. A mass-tort defendant could develop a compensation scheme and make offers to plaintiffs (or would-be plaintiffs). But nothing would force the plaintiffs into that scheme or require negotiation.[227] And plaintiffs would then have every reason to sue to better their bargaining position. That, in turn, could also rob future claimants of their compensation.

So too efforts to impose a workers’ compensation scheme in aggregate litigation have proven messy. Class actions over mass torts are all but dead in the wake of Amchem Products, Inc. v. Windsor[228] and Ortiz v. Fibreboard Corp.[229] And even when available, mass-tort class actions permit opt-outs.[230] Likewise, multidistrict litigation has struggled to develop compensation schemes that are attractive enough to obtain voluntary use by a supermajority of claimants.[231] And neither multidistrict litigation nor class actions offer protection for future claimants.[232]

Thus, bankruptcy offers much by way of regulatory partitioning, though not always through traditional roles of bankruptcy law. To be sure, bankruptcy is designed for coordinating creditor collection, one key regulatory partition. But it has no role in the out-of-bankruptcy reorganization sought in the Texas Two-Step. Nor does it have a traditional role in workers’ compensation, but its toolbox happens to be well-suited for creating a workers’ compensation scheme.

5. Pitfalls of Bankruptcy’s Regulatory Partition

The benefits of coordinating creditor collection and imposing a workers’ compensation scheme come with little or no downside. But there is some risk created by the Texas Two-Step in keeping assets outside of bankruptcy. After all, bankruptcy’s regulatory burdens on debtors exist for a reason: to protect creditors. Thus, a Manville bankruptcy avoids these pitfalls (though it forgoes the benefits as well), and the Two-Step embraces these benefits but with the risk of shortchanging claimants.

As canvassed above, in a Texas Two-Step, there is a risk that AssetCo will undertake risky projects, issue dividends to shareholders, or otherwise underfund tort victims’ recoveries.[233] The bankruptcy court will have no jurisdiction over AssetCo and will thus be ill-positioned to prevent such maneuvers. Likewise, tort victims will not own stock (directly or through a trust) in AssetCo and thus are at the mercy of AssetCo shareholders. And the management of LiabilityCo will both lack information on AssetCo and will be installed by AssetCo for the purpose of letting AssetCo run its business unimpeded.

C. Governance

Most of the pitfalls of regulatory partitions are ultimately challenges of governance, that is, “rules that provide for the powers and duties of the managers and the rights of the beneficial owners.”[234] To borrow from the governance terminology of corporate law, the challenges in designer bankruptcy center on care and loyalty.[235]

1. Care

Start with care. In any legal entity, the aim is to have management with the prudence, expertise, and information to maximize the value of the entity. Thus, “the duty of care requires that fiduciaries inform themselves of material information before making a business decision and act prudently in carrying out their duties.”[236] In designer bankruptcy, that is relevant for both the tort creditors’ entity (tort trust, LiabilityCo) and the business entity going forward (SuccessorCorp, AssetCo).

Manville. The Manville Model does handle issues of care well for both legal entities.

For the tort trust, the Manville Model anticipates hiring experts in finance (to ensure funding lasts and avoid underfunding), medicine (to better understand tort causation/harm), and administration (to develop and implement the compensation scheme).[237] So the tort trust has all the information it needs to set up a compensation scheme and pay victims based on their injuries. And the court will select, or allow tort claimants to select, prudent trustees.[238]

So too is the tort trust well-positioned to obtain information to oversee SuccessorCorp and protect tort claimants from any SuccessorCorp maneuvers that would harm them. It is, at a minimum, a shareholder[239] and likely the controlling shareholder.[240] The bankruptcy itself also generates significant information through schedules, disclosure statements, and the like.[241] That gives the trust access to information about SuccessorCorp[242] and some ability to chart the business’s course to benefit tort claimants.

As for SuccessorCorp, old management stay in place, as is standard for a Chapter 11 bankruptcy.[243] So the people who understand the business best remain in charge and can prudently operate the business.

Texas Two-Step. The Two-Step handles care duties well on the AssetCo front, where it mirrors a Manville SuccessorCorp. But it is less effective for LiabilityCo.

For AssetCo, old management stay in place. So those with knowledge of the business continue operating it, just as in Manville. That is the right result from the care perspective.

But when it comes to care and LiabilityCo, things are different. LiabilityCo has no shares in AssetCo and thus no right to access information.[244] Likewise, no covenants in the funding agreement permit LiabilityCo to monitor AssetCo[245] or demand the information. So too AssetCo never files for bankruptcy and thus need not provide information to the bankruptcy court—schedules, disclosure statements, and the like. All of this hobbles LiabilityCo’s ability to obtain key information and to oversee AssetCo. In turn, that restricts LiabilityCo’s ability to head off machinations by AssetCo that would shortchange tort victims.

Turning to the victims themselves, LiabilityCo, in its bankruptcy, need not establish a trust in its plan of reorganization.[246] And its plan, as a result, might not draw on the expertise in finance, medicine, and administration that proves valuable to tort claimants.

2. Loyalty

In addition to information, management of the tort creditors’ entity (trust or LiabilityCo) also need to have the right loyalties— “undivided and unselfish loyalty to the corporation”—to protect the tort victims.[247] Here again, the Manville Model proves better than the Texas Two-Step.

Manville. In a Manville trust, the trustees’ duty of loyalty runs to the tort victims (the beneficiaries), and so the trustees will not act to benefit shareholders or creditors of the SuccessorCorp.[248] Better yet, trustees owe a duty of impartiality to the beneficiaries of the trust.[249] That means they will not favor present claimants over future ones or vice versa. So the duty of loyalty runs, as it should, to the tort victims.