Lexipol The Privatization of Police Policymaking

This Article is the first to identify and analyze the growing practice of privatized police policymaking. In it, we present our findings from public records requests that reveal the central role played by a limited liability corporation—Lexipol LLC—in the creation of internal regulations for law enforcement agencies across the United States. Lexipol was founded in 2003 to provide standardized policies and training for law enforcement. Today, more than 3,000 public safety agencies in thirty-five states contract with Lexipol to author the policies that guide their officers on crucial topics such as when to use deadly force, how to avoid engaging in racial profiling, and whether to enforce federal immigration laws. In California, where Lexipol was founded, as many as 95% of law enforcement agencies now rely on Lexipol’s policy manual.

Lexipol offers a valuable service, particularly for smaller law enforcement agencies that are without the resources to draft and update policies on their own. However, reliance on this private entity to establish standards for public policing also raises several concerns arising from its for-profit business model, focus on liability risk management, and lack of transparency or democratic participation. We therefore offer several recommendations that address these concerns while also recognizing and building upon Lexipol’s successes.

Introduction

The conduct of American police is never far from the front page of the news. A wide range of policing issues—such as use of force, racial profiling, stop and frisk, roadblocks, Tasers, body cameras, and immigration policing—have garnered significant attention from community members, courts, advocacy organizations, and law enforcement agencies. Much of the discussion about improving police practices has focused on how best to regulate police conduct.[1] Gaining increasing traction in this discussion is the view that comprehensive internal police policies can guide the opaque and largely discretionary conduct of the police.[2] Those engaged in these discussions appear to assume that police departments, local governments, and nonprofits will play leading roles in the creation of police policies. However, the most significant national player in policing policy today is a private limited liability corporation—Lexipol LLC—that has, to date, received almost no scholarly attention.[3]

This Article is the first to examine Lexipol’s role in police policymaking. Lexipol explains on its website that it “offers a customizable, reliable and regularly updated online policy manual service, daily training bulletins on your approved policies, and implementation and management services to allow us to manage the administrative side of your policy manual.”[4] And Lexipol contends that it is “America’s leading provider of state-specific policy management resources for law enforcement organizations.”[5] But beyond the statements Lexipol posts about itself online, there is little publicly available information about Lexipol LLC’s products, its relationships with local jurisdictions, or the values that its products promote. Accordingly, we submitted public records requests to the 200 largest law enforcement agencies in California, seeking copies of their policy manuals as well as any communications or agreements with Lexipol. In response, we received thousands of pages of Lexipol-authored policy manuals, contracts, promotional materials, and e-mails.[6] We supplemented these public records responses with court records, newspaper stories, and other documentation of Lexipol’s work in California and around the country.

We found that Lexipol has expanded like wildfire since its founding in 2003. In only fifteen years, Lexipol has grown from a small company servicing forty agencies in California to a leading national police policymaker, replacing the homegrown manuals of local police departments with off-the-shelf policies emblazoned with the Lexipol LLC copyright stamp. Company employees and executives promote the fact that 95% of California law enforcement agencies subscribe to Lexipol[7]—an assertion consistent with agencies’ responses to our public records requests.[8] Lexipol’s rapid growth has allowed it not only to saturate the market in California but also to expand its reach to 3,000 public safety agencies in thirty-five states across the country.[9] Although Lexipol is not the only private entity to sell policies to local police departments in the United States, it appears to sell policy manuals and trainings to far more local law enforcement agencies than its competitors.[10] Indeed, law enforcement agencies in several states describe it as the “sole source provider” of standardized, state-specific law enforcement policy manuals.[11]

The key to Lexipol’s commercial success appears to be its claims to reduce legal liability in a cost-effective manner. Lexipol promotes itself as providing departments with a “policy that is always up to date” containing “legally defensible content” that will “protect your agency today.”[12] In fact, Lexipol’s promotional materials assert that departments using Lexipol have fewer lawsuits filed against them and pay less to resolve the suits that are filed.[13] Lexipol also argues that its policy manuals are higher-quality, more user-friendly, and less expensive than manuals that local jurisdictions could create on their own. Lexipol claims its standardized policies reflect court opinions, legislation, and what it calls “best practices” in each state.[14] Lexipol updates its policies, and local jurisdictions can incorporate those updates into their policy manuals with a click of a button. And Lexipol’s sliding-fee scale, which is based on the number of officers employed by the agency, makes this prepackaged deal particularly appealing for smaller departments that would not have the resources to develop and update policies on their own.[15]

Lexipol’s meteoric rise has significant implications for longstanding debates about the role policymaking might play in police reform. Beginning in the 1960s,[16] Anthony Amsterdam, Kenneth Culp Davis, Herman Goldstein, and others argued that comprehensive police policies could guide police discretion, improve police decisionmaking, and increase transparency.[17] These scholars advocated for a rulemaking procedure akin to that which exists for administrative agencies, whereby proposed policies would be subject to notice and comment by the public before promulgation, so as to invite “community reaction.”[18] In recent years, Barry Friedman, Christopher Slobogin, Eric Miller, and others have renewed these earlier calls for policing policies created by an administrative rulemaking process.[19] Yet Lexipol does not appear in these ongoing discussions about the types of police policies that will best guide police behavior, or the need for transparency and community engagement in the development of those policies.

As we reveal in this Article, Lexipol’s approach to police policymaking diverges in several significant ways from that long advocated by scholars and experts. Commentators have viewed police policies as a tool to constrain officer discretion and to improve officer decisionmaking. Lexipol, in contrast, promotes its policies as a risk management tool that can reduce legal liability. Commentators have long contended that the Supreme Court’s policing decisions are wholly inadequate to guide law enforcement discretion regarding racial profiling, stop and frisk, and other practices.[20] Yet Lexipol has resisted efforts to craft policies that go beyond the minimum requirements of court decisions because such policies might increase legal liability exposure.[21]

Moreover, the process by which Lexipol develops its policies is not consistent with the approach recommended by many policing experts who have emphasized the importance of transparent policymaking, with opportunities for public input.[22] Lexipol does not disclose information about who is making Lexipol’s policies and what interests are prioritized in their process. And although Lexipol informally receives feedback from subscribing jurisdictions about its policies, its policymaking process departs considerably from the transparent, quasi-administrative approach recommended by scholars and policing experts and adopted by some law enforcement agencies.[23] Also, Lexipol’s profit-seeking motive influences its product design in concerning ways. For example, Lexipol’s policies are copyrighted, and the company vigorously defends that copyright as a means of maintaining its profitability. Yet police policymaking has long been viewed as a collaborative enterprise. Departments across the country have traditionally shared their policies as a means of learning from each other and have borrowed liberally from each others’ policies. Lexipol’s business model impedes this generative process.[24]

In this Article, we do not reach any conclusions about how Lexipol’s policies compare to those adopted by law enforcement agencies that do not purchase Lexipol’s products. Indeed, some of these same critiques have been made of local law enforcement agencies that draft their own policies.[25] Yet because Lexipol appears to be the single most influential actor in police policymaking, its successes—and failures—have an outsized impact on American police policy. As Lexipol goes, so go thousands of law enforcement agencies across the country. And Lexipol’s for-profit status raises additional concerns that do not apply to government and nonprofit police policymakers.

By identifying Lexipol as a force to be reckoned with in American policing, this Article also begins an important conversation about the privatization of police policymaking. Privatization scholars tend, in varying degrees, to applaud privatization of government functions as cost-effective[26] or to despair that privatization impedes democratic values.[27] Our research regarding the privatization of police policymaking offers evidence to support both views. Lexipol appears to have solved a problem that has proven elusive to those advocating for police policymaking—how to promulgate police policies in the almost 18,000 highly localized law enforcement agencies across the country.[28] And agencies that contract with Lexipol may well have a more complete and up-to-date policy manual than they would have developed on their own—Lexipol subscribers quoted on its website certainly make that claim.[29] But our research also raises serious questions about the values, process, and expertise called upon to create the Lexipol policies that regulate the public police.

Many believe—and we agree—that police departments need comprehensive and detailed policies to guide officer discretion and should engage with local communities in some manner when shaping those policies. We additionally believe that plans to improve law enforcement policymaking must recognize the prevalence of Lexipol and take account of the strengths and weaknesses of its approach. Accordingly, we recommend that Lexipol be more transparent about its policymaking process so that local governments can make more informed decisions about the policies that guide their law enforcement agencies; that local governments and courts take a more active role in police policymaking; and that nonprofits and scholars develop more easily accessible alternative model policies that are compatible with Lexipol’s user-friendly platform. We believe that these recommendations will encourage local jurisdictions to craft their own policies when possible and, when contracting with Lexipol, view the company as a first—but not final—step in the policymaking process.

I. The Rise of Lexipol

In this Part, we share our findings about Lexipol’s founders, its products, and its relationships with the local governments it serves. In conducting this research, we first gathered information from Lexipol’s website, financial filings, press releases, news sources, and court documents. We supplemented this research with public records requests to the 200 largest police and sheriffs’ departments in California, seeking each department’s policy manual and any dealings with Lexipol LLC—including contracts, payments, correspondence, and other memoranda.[30] We chose to conduct this research in California, where Lexipol was founded. Soon thereafter, we were contacted by a vice president at Lexipol who had learned about our public records requests from Lexipol subscribers. We had several conversations with this vice president and other Lexipol executives about the company’s business model and process for creating its policy manuals.

In this Part, we provide a descriptive account of Lexipol’s services, drawn from the information we gathered. We begin by introducing what we know about Lexipol’s founders and employees. We then describe the company’s products, cost structure, sales methods, and growth. Later, in Part II, we build on our findings to analyze Lexipol’s model of police policymaking.

A. People

Lexipol LLC was founded in 2003 by Bruce Praet, Gordon Graham, and Dan Merkle.[31] Praet, an attorney and former law enforcement officer, appears to have had the initial vision for the company. While working as a partner at the Southern California law firm of Ferguson, Praet and Sherman, Praet developed a specialty in “aggressively defending police civil matters such as shootings, dog bites and pursuits.”[32] In the late 1990s, Praet’s firm assisted the California agencies he represented to reduce liability exposure by recommending they adopt a policy he authored on vehicular pursuits.[33] A 1959 California law provided that agencies with a written policy for vehicular pursuits were immunized from certain forms of civil damages.[34] By drafting such a policy for his clients, Praet shielded them from civil liability for these types of claims.

Praet’s experience developing a model policy for vehicle pursuits inspired him to create a more comprehensive set of policies that local law enforcement agencies could purchase. Working with Geoff Spalding, a Police Captain with the Fullerton Police Department, Praet created a model California law enforcement manual based on Fullerton’s policies.[35] Praet used this model when the Escalon Police Department retained his firm to write its entire policy manual in 1999. By 2002, the firm maintained the policy manuals for about forty California-based law enforcement agencies.[36]

In 2003, Praet founded Lexipol with Gordon Graham and Dan Merkle, and transferred his policy development work from his law firm to the new company.[37] Graham, also a former law enforcement officer and law school graduate, additionally has a master’s degree in Safety and Systems Management.[38] In the 1980s, while a sergeant in the California Highway Patrol, Gordon developed daily trainings for officers that he called the “SROVT program: Solid, Realistic, Ongoing, Verifiable, Training.”[39] In the early 1990s, Graham began adapting his training programs for private sector and public safety organizations.[40] When Graham joined Lexipol as co-President, he drew on his expertise in public entity risk management to develop training materials to accompany the manuals.[41]

Dan Merkle served as Lexipol’s first Chairman and CEO.[42] Merkle has a background as a corporate executive[43] and was recruited to focus on building the company’s infrastructure.[44] When Merkle left Lexipol in 2013 to join a media technology company,[45] Ron Wilkerson became the new CEO of Lexipol.[46] As the company has grown beyond its original founders, it has hired scores of attorneys, marketing specialists, and account managers.[47]

Although Lexipol applauds the “all-star team of public safety veterans”[48] that drafts its polices and trainings, there is no publicly available information about who these public safety veterans are. We found information about Praet and Graham, but could find no information about the identities or credentials of their 120 employees.[49] Indeed, none of the marketing materials that we obtained from the California jurisdictions we surveyed included information on names or credentials of Lexipol’s employees. When we spoke to company executives about this issue, they provided us with the photos, names, and titles of ten Lexipol executives, and one vice president told us that he would love to include photos and bios of staff on Lexipol’s website, but that he had not yet had a chance to do so.[50] Another vice president observed that law enforcement agencies can always call Lexipol to learn more about the people who develop policies.[51]

Bruce Praet was equally unforthcoming about Lexipol’s employees in a recent deposition taken after Lexipol was sued over its Taser policy.[52] Praet testified that Lexipol identifies best practices by relying on their internal subject matter experts and feedback from their subscriber agencies.[53] Yet when Praet was directly asked whether Lexipol “employ[s] subject matter experts on different areas of law enforcement practices who determine what best practices are,” he acknowledged that they did not.[54] He explained: “We don’t have a specific subject matter expert on a specific topic, but a good number of our people are law enforcement background, so there’s a wealth of information that we draw upon, depending on the subject.”[55] Similarly, Praet could not (or would not) identify Lexipol employees who had particular expertise in Tasers.[56] Instead, he said, Lexipol “had a wealth of people who have a significant amount of information about Tasers, but not one person who was the go-to person.”[57]

B. Products

On its website and in its promotional materials sent to potential law enforcement customers, Lexipol markets three main products: (1) a policy manual, (2) Daily Training Bulletins, and (3) implementation services.[58] In this section, we share what we have learned about each product.

1. Policy Manual.—Lexipol’s signature product is its copyrighted policy manual.[59] Lexipol has a “global master” manual that is based on federal standards and best practices.[60] It has used this global master to create “state master” manuals that incorporate state-specific standards.[61]

There is limited public information available regarding how Lexipol goes about drafting the policies contained in its manuals. We know from speaking with executives at Lexipol that they work with a team of company attorneys and former law enforcement officials to review court decisions, legislation, and other materials applicable to a state.[62] Lexipol also considers media reports, client feedback, trends in law enforcement, and reports by outside groups including the Department of Justice, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and the National Institute of Justice.[63] Anecdotal evidence also plays a significant role in Lexipol’s policy development process. As Bruce Praet explained in a deposition, “we’re constantly getting anecdotal information, and I can’t speak for everybody, but everybody on the Lexipol staff, when they become aware of something that may impact policy . . . they share that and then that is round-tabled, and if it has a policy impact, then that’s incorporated into our content.”[64]

The Lexipol vice presidents we interviewed offered little guidance about how Lexipol ultimately weighs and balances these various sources of information. They simply reported that policies are designed by looking at all available evidence and having all relevant employees weigh in on how the policies should be crafted.[65] As Bruce Praet similarly reported in his deposition, “if an issue comes up, typically, among the attorneys and subject matter experts that we have, we would, for lack of a better term, turkey shoot or brainstorm the issue and see what we could come up with [as] an appropriate response.”[66] Once Lexipol decides to develop a policy, employees determine how the policy should be written. The vice presidents with whom we spoke described this process as “a challenge” that often results in disagreements between the legal team (which is focused on risk to its agency clients in the courtroom) and the content-development team (which is focused on risk to law enforcement officers on the street).[67] How these disagreements resolve “varies based on what the issue is and the timing.”[68] Lexipol does not make public the substance of its deliberative process or the justifications for its policy decisions. Indeed, Lexipol appears to keep no discoverable records of its decisionmaking process regarding policy content.[69]

Agencies that contract with Lexipol are provided a draft state-specific policy manual for review.[70] The draft manual is typically accompanied by a diagram (reproduced in Figure 1) that captures the framework that Lexipol uses for categorizing the policies included in its manuals. According to this typology, some policies are required by federal or state law, whereas others are considered “best practices” or “discretionary.” Lexipol’s draft policy manuals are coded to inform readers of the categorization of each proposed policy.[71]

Figure 1: The Components of a Lexipol Policy Manual[72]

Jurisdictions can choose whether to adopt, reject, or modify each policy.[73] Lexipol advises its users to “fully understand the ramifications and use caution before changing or removing” policies derived from federal and state law.[74] Policies characterized as “best practices” are reportedly “considered the currently accepted best practice in the public safety field,” and Lexipol advises adopters that “[t]his content may be changed if necessary, with caution.”[75] Discretionary policies are described as those “that may or may not be important for your agency” and “may be changed or removed as needed.”[76] Jurisdictions understand this message: as one agency representative told us in responding to our public records request, those Lexipol policies designated as “best practices” or “discretionary” are “optional,” but those that are the “law” are required.[77]

In promotional materials, Lexipol describes its manual as “a complete regulatory and operational policy manual” that “may be accepted for use immediately.”[78] Nonetheless, Lexipol does take some steps that enable local jurisdictions to customize their manuals. When Lexipol first begins working with a department, it asks the department to fill out a questionnaire that is used by the company to ensure that the terminology used in the manual (such as “officers” or “deputies”) is consistent with that used by the particular agency.[79] Once Lexipol receives the questionnaire, its staff members spend an average of ten to fifteen hours “to further refine the manual to the specific needs of the agency.”[80] Agencies may also work with Lexipol to customize certain policies or supplement the manual with original policy content.[81] For those agencies that wish to author some of their own policies, Lexipol issues a style guide in which it describes “house rules for spelling, punctuation, citations and other style issues.”[82]

Lexipol executives informed us that they also make policy “guide sheets” available to their subscribers that offer additional information agencies can use when deciding whether to customize their manuals.[83] But when we requested a copy of this policy guide, Lexipol refused to provide us with a copy[84] and none of the California agencies we queried provided us with guide sheets or a policy guide in response to our public records requests.[85] Indeed, when we asked a detective at the Fontana Police Department—a Lexipol subscriber—about Lexipol’s policy guide, he said that they had never “heard of” or “seen” such a guide.[86] Lexipol executives conceded that the guide is a “well-kept secret” because it is difficult for subscribers to access online.[87] Lexipol marketing material that we obtained from the Santa Clara Police Department included a single sample “guide sheet” for a policy on Records Release and Security. The sample “guide sheet” stressed the necessity of adopting Lexipol’s policy with little or no modification: “This is a highly recommended policy that all agencies should have as part of their manual. . . . [W]e have provided you with a comprehensive policy . . . . [I]t is unlikely that you will want to modify it to any great extent.”[88]

The Lexipol-issued policy manuals we reviewed from California law enforcement agencies follow a nearly identical format.[89] After an initial page concerning the law enforcement code of ethics and a page for a mission statement, there is a table of contents that covers the role of law enforcement officers, the organizational structure of the department, general operations, patrol operations, traffic operations, investigation operations, equipment, support services, custody, and personnel.[90] Each section has several policies, and each policy has an identical numbering system and title. For example, Policy 310 concerns “Officer-Involved Shootings and Deaths”; Policy 402 concerns “Racial- or Bias-Based Profiling”; and Policy 1014 concerns “Sick Leave.”

2. Daily Training Bulletins.—Daily Training Bulletins (DTBs) are the second principal component of the Lexipol platform. The company describes DTBs as a system of short “training scenarios” that give departments and officers the ability to understand their policies and apply them in practice.[91]

The concept of short daily trainings is based on founder Gordon Graham’s philosophy that “every day is a training day.”[92] The approach focuses on “high risk, low frequency events” that, according to Lexipol, “pose the greatest risk to agencies and their personnel.”[93] DTBs are made available to agency personnel via any web-enabled device, including a mobile phone, in-car computer, or desktop computer.[94] Company executives informed us that each DTB training is designed to be completed in only two minutes.[95] They explained that this is because two minutes of daily training—which amounts to one hour per month and twelve hours per year—is sufficient to satisfy minimum police training requirements set by some states’ Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) organizations.[96]

Figure 2: A Lexipol Daily Training Bulletin[97]

Figure 2 contains a sample DTB taken from Lexipol’s promotional materials. According to Lexipol’s founding CEO Dan Merkle, DTBs follow “the well-respected ‘IRAC’ (Issue, Rule, Analysis, Conclusion) method of training commonly used in law schools.”[98] Using this standardized IRAC format,[99] all DTBs begin with a three to four sentence scenario that could occur in the field.[100] Next, the DTB provides the number of the Lexipol policy that guides police decisionmaking in the scenario.[101] The officer is asked to respond to a multiple choice or true/false question that highlights application of the policy to the scenario.[102] Finally, the DTB provides a short analysis of why the policy applies and summarizes the learning objective for the training.[103]

For those departments that choose to supplement their Lexipol policy manuals with DTBs, officers can receive one of these short trainings each day during roll call. As Deputy Chief of the Simi Valley Police Department explains in an advertisement on Lexipol’s web page: “It can be challenging for the supervisor to come up with relevant topics for roll call training, but having the DTBs gives us a pool of topics to choose from.”[104] Lexipol keeps a record of each officer’s participation in the training exercises.[105]

3. Implementation Services.—In addition to the policy manual and DTBs, Lexipol offers departments a range of consulting services to assist in implementing and managing their Lexipol products.[106] For example, agencies can hire Lexipol to draft custom policies based on specific needs, as well as to ensure that departments’ DTBs are consistent with any custom policies that the departments have modified.[107] Agencies can choose between a basic “silver plan” that provides a “quick start,” or go with a “platinum” plan that will “help with implementation.”[108] As a Lexipol executive told the Beverly Hills Police Department in 2016, departments can retain a “Project Manager” to “facilitate” the “entire project” and “do all the heavy lifting when it comes to edits, linking policy to procedure and anything else you would need.”[109]

4. Cost.—The cost of a Lexipol subscription varies significantly depending on the size of the agency and the services purchased. The initial start-up cost for the first year generally includes access to the policy manual, policy updates, and DTBs. The cost of a basic subscription to the Lexipol service depends upon the size of the agency. For example, Lexipol charged the Calaveras County Sheriff’s Office, which has fifty deputies, $8,600 for the first year of services;[110] Lexipol’s proposal to the Simi Valley Police Department for up to 150 full-time sworn officers priced the first year at $15,150.[111] The larger Long Beach Police Department, which is no longer a Lexipol client,[112] was quoted $24,950 for up to 820 full-time sworn officers.[113]

Once an agency adopts the Lexipol manual, it can choose to subscribe to Lexipol’s updating service, as well as its Daily Training Bulletins, for an additional fee.[114] Subscribers to the updating service will periodically receive revised policies from Lexipol.[115] When departments accept these policy revisions, they are incorporated automatically into the existing policy manual.[116] Again, prices for these services vary based on the size of the department. For example, the Simi Valley Police Department (which has 127 sworn officers) was quoted $13,250 for ongoing updates and DTBs,[117] while the Long Beach Police Department (which has 968 sworn officers) was quoted $64,500.[118]

Beyond these standardized services, jurisdictions can pay additional fees for consulting services. For example, the Baltimore (Maryland) Police Department paid Lexipol $340,000 in 2013 for “overhauling the manual providing the basis for Standard Operating Procedures and providing professionally created training bulletins.”[119] Similarly, the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) paid Lexipol $295,000 to help develop policies required by the Department of Justice following a civil rights investigation of the NOPD.[120]

Sometimes the costs for Lexipol are partly or wholly covered by municipal insurers.[121] More often, local jurisdictions pay for Lexipol’s products directly through their general city or county budgets,[122] or through the law enforcement agency’s budget.[123] One jurisdiction reported using forfeiture funds to pay Lexipol.[124]

C. Sales Techniques

Lexipol LLC engages in an aggressive marketing campaign with its potential customers. The company hosts booths at government and law enforcement conventions to promote its wares.[125] For example, in 2017, Lexipol representatives attended the Kansas Sheriff’s Association Fall Conference, the New Jersey Association of Chiefs of Police Annual Mid-Year Meeting, and the Oregon State Sheriff’s Association Annual Conference, among other conferences and events.[126] Lexipol clients who visited the Lexipol booth at the 2016 conference for the International Association of Chiefs of Police could “enter [its] drawing to win a free iPad air 2.”[127]

Lexipol also attracts clients by sponsoring free webinars on hot policing issues such as “Immigration Violations & Law Enforcement” or “How Not to Speak to the Media” that may encourage departments to purchase their services.[128] One e-mail sent to the Madera Police Department explained that state law “offers unprecedented protection from liability risks associated with police pursuits” but that “[m]any law enforcement agencies fall short in meeting these requirements and are exposing their cities and counties to much greater financial risk than necessary.”[129] The e-mail then invited representatives of the department to attend a free thirty-minute educational webinar.[130]

Some of the solicitation correspondence we collected reveals that Lexipol researches the target departments to learn about their particular law enforcement challenges. For example, in 2015 Lexipol approached the Chief of the San Francisco Police Department, writing: “I recognize the current challenges your department is facing. I reviewed your policies and they are severely outdated and insufficient. Case in point, you don’t have a Department’s Use of Social Media policy and your Use of Force policy hasn’t been updated/revised since 1995.”[131] Lexipol provided the Chief with sample policies and a few ideas for improving his department’s policies, and asked for a fifteen-minute call to discuss Lexipol’s services. Similarly, a Lexipol Client Services Representative reached out to the Chief of the Beverly Hills Police Department to complement him for “the amazing manner in which” his officers “presided over the Trayvon Martin protests recently,” before going on to warn that “with recent racial tensions rising, now would be the perfect opportunity to re-examine ways Lexipol can help ensure the safety of your officers to avoid any potential risks.”[132]

Lexipol also appears to have directed its advertising to municipal liability insurers that provide liability insurance to small governments. Our research has revealed that insurance companies will sometimes reduce their annual premium for cities that contract with Lexipol, or even pay outright for their insureds’ Lexipol contracts.[133] In California, for example, more than 100 law enforcement agencies are given access to Lexipol as a benefit of their insurance agreement with one large insurer, the California Joint Powers Insurance Authority.[134]

Lexipol has a standard sales pitch that was repeated in communications with multiple California jurisdictions. The message describes the high costs of “[o]utdated [p]olicy and [l]ack of [t]raining,” measured in “Increased Risk and Liability to Deputies, Department and Community,” “Damaged [sic] to Reputation, Negative news Headlines and/or Viral Footage,” “Lawsuits,” “Legal Fees,” “Settlements,” “Injury and/or Death,” and “Distrust with the Community.”[135] Lexipol’s solicitation e-mails to department officials include catchy taglines such as “Are Outdated Policies Putting Your Agency at Risk?,”[136] “Is Your Use of Force Policy Properly Protecting You?,”[137] and “What is the Cost of Outdated Policy and Lack of Training?”[138] After attracting the attention of top officials, Lexipol makes a web-based or in-person presentation to the department that highlights the Lexipol approach and the benefits of entering into a contract with Lexipol.[139] Lexipol may also make presentations to city council or other government officials who make the ultimate decision about whether to purchase Lexipol’s services.

Although Lexipol describes many different types of risk in its marketing materials, liability risk plays the central role. As Lexipol’s CEO Dan Merkle stressed in a letter to Captain Bob Gustafson of the Orange Police Department, the value in Lexipol’s service is that it provides “[p]olicies that are court tested and successful in withstanding the numerous legal challenges prevalent today.”[140] Lexipol constantly warns its potential customers that without Lexipol they are at risk of having their outdated policies turn up “downstream in litigation” and make the day for “plaintiff’s lawyers.”[141] In a document prepared for the Chula Vista Police Department, Lexipol summed up why its clients choose Lexipol this way: “Law Enforcement agencies by their nature are a high frequency target for litigation. It is the most compelling reason why our customers choose our services.”[142]

Lexipol does not outline the precise ways in which updated policy manuals will reduce liability risk, but it does report that its products have in fact “helped public safety agencies across the country reduce risk and avoid litigation.”[143] In a PowerPoint presentation offered to several departments in our study, Lexipol included a slide (reproduced as Figure 3) claiming that adoption of Lexipol policies was associated with reduced litigation costs. According to the slide, Lexipol’s Oregon clients that “fully adopted” Lexipol reportedly had a 45% reduction in the “frequency of litigated claims” and a 48% reduction in the “severity of claims paid out,” as compared to nonparticipating agencies.[144]

Figure 3: Lexipol Risk Management Analysis[145]

Other Lexipol promotional materials tout similar litigation-cost savings. Materials provided to the San Francisco Police Department in 2016 quoted one risk management association as saying this about Lexipol: “Two years post-Lexipol implementation, perhaps the most positive trend is that Lexipol users have 69% fewer litigated claims compared to pre-Lexipol implementation. And, the claims that are litigated have, on average, $7k paid out instead of $20k pre-Lexipol.”[146] A company press release from 2014 claimed that “a 10-year third-party study demonstrated a 54% decrease in litigated claims and a 46% reduction in liability for agencies that adopted Lexipol.”[147] Lexipol additionally provided us with marketing materials that tout “37% fewer claims,” “45% reduced frequency of litigated claims,” “48% reduction in severity of claims,” and “67% lower incurred costs.”[148] Lexipol’s promotional materials identify insurance company claims data as the source for these findings, but Lexipol provided us with no dataset, study, or other evidence to support these assertions by the company.[149]

Lexipol’s marketing materials also contain detailed testimonials of jurisdictions explaining why they chose to adopt Lexipol. The justifications offered repeatedly echo Lexipol’s claims that its products insulate jurisdictions from liability. For example, Sheriff Blaine Breshears of the Morgan County Sheriff’s Office in Utah explains in an advertisement on Lexipol’s website that after attending “a class taught by Lexipol co-founder and risk management expert Gordon Graham,” he became concerned that his outdated policy manual “could actually be a serious liability.”[150] After adopting Lexipol, however, Sheriff Breshears successfully defended his agency against a use of force lawsuit: “[A]s soon as the attorneys discovered that we have Lexipol, they said, ‘We won’t have an issue there.’ Our policies were never in question.”[151]

In the records we obtained from 200 California jurisdictions, we found that several departments justified the cost of Lexipol’s products with claims that Lexipol’s policies would protect them from possible lawsuits. The Chief of Police of the City of Baldwin Park explained in a memo to the Mayor and City Council that “[n]ot having an updated policy manual [from Lexipol] could result in litigation against the city.”[152] The Riverside Police Department similarly told the City’s Purchasing Division that without Lexipol it risked “continuing to fall behind as court decisions, laws, and law enforcement practices change. This deficiency can potentially expose the City, Department, and Officers to unnecessary liability and harm.”[153] And the City of South San Francisco’s Chief of Police told the Mayor and City Council that Lexipol would “assist in mitigating any litigation that is related to the policies of the Police Department.”[154]

In addition to litigation-risk reduction, Lexipol promotes its products as cost effective by saving jurisdictions the time and money of developing their own policies. Lexipol repeatedly noted in its promotional materials that agencies would spend far more than Lexipol’s modest subscription cost to write and update policing policies on their own.[155] As Lexipol warned the Long Beach Police Department during contract negotiations: “A fully burdened officer can cost an agency upward of $100K in salary and benefits. Most small to mid-sized agencies assign one officer to update and maintain their policy manual, which can consume 50% to 80% of the officer’s time.”[156] In case studies on Lexipol’s website, chiefs of small agencies explain that they did not have the capacity to create and maintain policies on their own and applaud Lexipol for providing up-to-date policies in a cost-effective manner.[157] Several California departments in our study justified their adoption of the Lexipol service in similar terms. For instance, the Riverside Police Department told city officials charged with approving the Lexipol contract that “the salary savings realized over having Department personnel research the constantly changing legal requirements and make the needed policy changes, would likely far exceed the cost of this service.”[158]

D. Growth

Lexipol does not publish a list of its clients and refused to provide us with a list of its clients.[159] However, the company regularly makes public statements about the number of law enforcement and other public safety agencies that use Lexipol policies and boasts of the growing number of states that the company now services. In order to chart the company’s growth, we collected the company’s own statements from press releases, the company’s web page, news articles, and marketing materials provided by Lexipol clients in response to our public records requests.

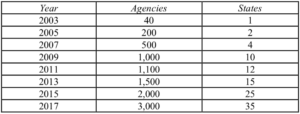

Our research reveals that the company has grown from forty California-based agencies in 2003 to 3,000 public safety agencies across thirty-five states in 2017.[160] This astronomical growth has been mainly focused on police and sheriff’s departments, but also includes fire departments and other public safety agencies.[161] Table 1 reports these data in two-year increments.

Table 1: Lexipol’s Growth, by Agencies and States (2003–2017)[162]

Not surprisingly, Lexipol enjoys a strong market presence in California, where the company began. Lexipol executives claim that as many as 95% of California law enforcement agencies now have their policies written by Lexipol.[163] Our public records requests to the 200 largest police and sheriff’s agencies in California reveal that only twenty-six agencies (13%) are independent, meaning that they create their own policy manuals and have no relationship with Lexipol. The 174 remaining departments—or 87% of our sample—purchase Lexipol’s services or receive them through their insurer. Of these 174 agencies, all but eight have adopted a copyrighted Lexipol policy manual for their police or sheriff’s department.[164]

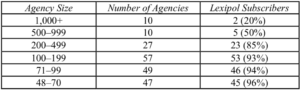

We also find that the smaller agencies are especially likely to use Lexipol’s products. Among agencies with 1,000 or more officers, only 20% subscribe to Lexipol. In contrast, among agencies with fewer than 100 officers, 95% subscribe to Lexipol. The complete results of this size-based analysis are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2: Lexipol Subscriptions Among the 200 Largest Police

and Sheriff’s Departments in California, by Agency Size (2017)[165]

In 2010, Lexipol was ranked the twenty-fourth fastest-growing private company in Orange County, California.[166] In 2012, Lexipol was ranked 387 on Deloitte’s Technology Fast 500, “a ranking of the 500 fastest growing technology, media, telecommunications, life sciences and clean technology companies in North America.”[167] Lexipol was purchased by The Riverside Company in 2014.[168] The Riverside Company describes Lexipol as a company with “tremendous opportunity for growth due to a largely untapped market.”[169] Riverside plans to help Lexipol expand into new states and offer clients additional risk management services.[170]

II. The Significance of Lexipol

Although there are other private, nonprofit, and government entities that draft police policies, Lexipol is now a dominant force in police policymaking across the country. Lexipol has saturated the market in California and provides its services to more than 3,000 public safety agencies in thirty-five states across the country. There is every reason to expect that Lexipol will play a controlling role in police policymaking in more states in the future.

Lexipol has achieved a goal that has proven elusive—disseminating and updating police policies for thousands of law enforcement agencies. Lexipol’s business model appears to be the key to its growth. Lexipol has successfully marketed its policy and training products as risk management tools that can insulate police and sheriff’s departments from liability. The company has also promoted its policies and trainings as being of higher quality than local jurisdictions could create on their own—the products are available online, are state-specific, are updated to reflect changes in governing law and best practices, and allow jurisdictions to track when their employees have viewed policies and completed trainings. Lexipol’s products are therefore viewed as money-savers twice over—they reduce the cost of creating comparable policies and trainings, and those policies and trainings reduce the cost of litigation. Lexipol’s service has been particularly popular with smaller jurisdictions that lack the personnel or resources to create and update their own policies and trainings. Mayors, city councils, and insurers have been willing to pay Lexipol’s fees, apparently convinced that they more than pay for themselves given the litigation and risk management savings associated with Lexipol’s products.

Yet Lexipol’s approach appears to run contrary to the purposes, values, and processes recommended by two generations of advocates for police policymaking. In this Part, we consider three main areas of divergence: Lexipol’s unwavering focus on liability risk management, its lack of transparency, and its privatization of the policymaking role.

A. Liability Risk Management

Police policies have long been viewed as a means of regulating officers’ vast discretion. When President Lyndon B. Johnson’s National Crime Commission studied policing practices in 1967, it found that police did have some internal rules.[171] However, the few rules that existed were “mostly of a housekeeping character—how to wear the uniform, how to carry the gun, whether to scribble a report in triplicate or in quadruplicate, and what to do with the copies.”[172] Police manuals did not address “the hard choices policemen must make every day.”[173] That is, they did not resolve how officers should exercise discretion in high-frequency scenarios, such as “whether or not to break up a sidewalk gathering, whether or not to intervene in a domestic dispute, whether or not to silence a street-corner speaker, whether or not to stop and frisk, whether or not to arrest.”[174] The end result was that police engaged in policymaking in an ad hoc way as they went about their work, rather than answering to a centralized set of rules when making the important discretionary decisions inherent to policing.

Scholars and policing experts in the 1950s and 1960s hoped that comprehensive police policies would give an officer “more detailed guidance to help him decide upon the action he ought to take in dealing with the wide range of situations which he confronts and in exercising the broad authority with which he is invested.”[175] Internal policies could also help to achieve “uniformity” in police conduct within an agency, including by ensuring that when “individual police officers confront similar situations, they will handle them in a similar manner.”[176] Today, scholars and experts echo concerns from half a century ago about the need to guide police discretion and the potential for comprehensive police policies to serve that role.[177]

Lexipol has a different set of goals and values that guide its approach to police policymaking. While scholars and experts have long viewed police policies as a means of limiting officer discretion, Lexipol appears to view its products primarily as a means of reducing legal liability. Lexipol relentlessly markets its products to jurisdictions by arguing that it will decrease the number of claims brought against police departments and the amount that jurisdictions pay in settlements and judgments in cases that are filed. We do not condemn Lexipol for focusing on limiting liability risk—its claim that Lexipol policies reduce financial liability appears to be a powerful selling point for local jurisdictions and insurers that purchase its services.[178] We also recognize that efforts to reduce liability risk will sometimes lead to the same policy prescriptions as efforts to constrain officer discretion.[179] But Lexipol’s focus on reducing liability risk is sometimes in tension with longstanding efforts to guide and restrict officer discretion through police policies.

This tension can be seen in recent debates about use of force policies. Over the past few years, several groups—including the Fraternal Order of Police, the International Association of Chiefs of Police, the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF), academics, and nonprofit advocacy organizations—have recommended new policing policies to reduce unnecessary and excessive use of force.[180] Included in this approach are policies requiring that police use de-escalation techniques with suspects, refrain from shooting into moving vehicles, and intervene if another officer might use excessive force.[181] Although Lexipol’s California state master policy manual contains some of these concepts,[182] Lexipol has issued a series of public statements critical of these recently issued model use of force policies because language in these policies restricts officers’ discretion in ways that could expose them to legal liability.

Soon after several prominent law enforcement groups issued a National Consensus Policy on Use of Force, Lexipol’s founding partner, Bruce Praet, posted an article to Lexipol’s website titled National Consensus Policy on Use of Force Should Not Trigger Changes to Agency Policies.[183] Praet cautioned law enforcement agencies against adopting several of the model policies because they used the word “shall.” Although the model policies’ use of “shall” was presumably geared to constrain officer discretion, Praet discouraged agencies from adopting that language because plaintiffs’ attorneys would “highlight” that type of language as a way of showing that officers had violated policy.[184] According to Praet, the need to shield officers from liability is “why Lexipol policy clearly defines the difference between ‘shall’ and ‘should’ and cautions against the unnecessary use of ‘shall.’”[185] Lexipol posted an article by a police chief offering a similar admonition against adopting a model use of force policy recommended by PERF that prohibited shooting at moving vehicles. His argument against the model policy was also based on limiting legal liability: “Policy language that definitively prohibits an action will inevitably result in a situation where an officer violates the policy under reasonable circumstances, which in turn can create issues that must be dealt with if litigation results.”[186]

Bruce Praet has additionally criticized PERF for recommending that use of force policies “go beyond the legal standard of ‘objective reasonableness’ outlined in the 1989 United States Supreme Court decision Graham v. Connor.”[187] PERF’s recommendation was motivated by an interest in limiting officers’ discretion to use lethal force. As PERF explained:

[The Graham] decision should be seen as “necessary but not sufficient,” because it does not provide police with sufficient guidance on use of force. . . . Agencies should adopt policies and training to hold themselves to a higher standard, based on sound tactics, consideration of whether the use of force was proportional to the threat, and the sanctity of human life.[188]

PERF’s position is consistent with decades of scholarship about the limitations of court opinions as a guide for police policymaking. Those who advocate for improved police policies are generally skeptical of the ability of courts to provide needed guidance to agencies creating police policies.[189] Judicial decisions do play a critically important role in police policies, as they create a floor that cannot be violated.[190] Because courts are focused on the constitutionality of officer behavior, their decisions will, by definition, articulate the bare minimum that officers must do to avoid violating the Constitution.[191] However, due to their “case-by-case and relatively intuition-laden” approach, courts are not necessarily well-situated to articulate best practices.[192] As a result, most experts agree that police policymaking should draw from multiple sources, including input from local community members regarding their experiences with police, best practices recommended by policing experts, research about the impact of various policies, and analyses of the costs and benefits of different approaches.[193]

In contrast to decades of scholarship on the subject, Praet has criticized the notion that police use of force policies should “go beyond” the requirements announced by the Supreme Court in Graham. He writes:

Several years ago, our forefathers decided that there would be nine of the finest legal minds in the country who would interpret the law of the land. For almost 30 years, law enforcement has learned to function under the guidance of the Supreme Court’s “objective reasonableness” standard. What would happen if each of the 18,000+ law enforcement agencies in the United States formulated their own standard “beyond” Graham?[194]

To be sure, Lexipol’s policies are not solely guided by court decisions. Lexipol makes clear in its promotional materials that some of its policies are inspired by what it calls “best practices” that are not mandated by statutes or court decisions.[195] But use of force policies raise a different question for policymakers: When there is a court decision or statute that prohibits certain officer behavior, and expert opinion that recommends additional restrictions on officer behavior, should the policy conform to the court decision or to the higher standard recommended by experts? Statements by Praet and other Lexipol spokespeople about use of force suggest that Lexipol’s focus on liability risk management may cause it to draft policies that maximize officer discretion and hew closely to court decisions when such decisions exist—and that those inclinations may conflict with experts’ views on best practices.

Lexipol’s focus on liability risk management may influence its product design in other ways. For example, Lexipol promotes its officer DTB training program as focused on “high-risk, low-frequency behaviors” including use of force, use of electronic control devices, vehicle and foot pursuits, and crisis intervention incidents.[196] According to Lexipol, its DTB trainings are designed to be “a cost effective training delivery method that serves as a substantial safety net” against lawsuits.[197] Yet, although low-risk, high-frequency events—such as traffic stops and searches—are less likely to result in litigation,[198] such events threaten other risks, including risks to community safety and trust in the police. As John Rappaport has observed, a focus on reducing liability risk may shortchange other important areas of police activity.[199]

Lexipol’s focus on liability risk management may also cause it to design products that reduce the frequency with which plaintiffs sue or the amount they recover without reducing the occurrence of the underlying harms. For example, Lexipol has designed its policy and training software so that officers can “acknowledge” that they received updated policies and participated in Lexipol’s trainings.[200] According to the company, this acknowledgement protocol can help in litigation, as it provides evidence that officers were informed and trained on the policies.[201] Yet we found no corresponding marketing materials suggesting that Lexipol designs its trainings to improve officer understanding of harmful practices by drilling down on these challenging topics, or that the two-minute training format is well-suited to achieve these goals.

Finally, Lexipol’s focus on risk management appears to influence the ways in which the company evaluates the efficacy of its policies. Lexipol consistently promotes its policies as reducing the frequency of lawsuits and the cost of settlements and judgments. The marketing materials we obtained make specific claims about the reduction in such costs enjoyed by subscribers.[202] But Lexipol does not make any claims about whether its products advance other important policing goals, such as enhanced trust within communities or fewer deaths of persons stopped by the police.[203] Also notably absent is any claim about whether Lexipol’s products reduce the frequency with which police officers engage in unconstitutional conduct that does not frequently result in litigation.[204] Lexipol’s decision to focus on liability risk management makes sense; it certainly has been an effective marketing strategy with local governments. Nevertheless, this focus threatens to crowd out other values that can be advanced through police policies.

Because Lexipol does not publicly disclose information about its drafting process, it is impossible to know the extent to which liability risk management interests have influenced drafting choices for individual policies, decisions about which trainings to develop, or assessments of policy efficacy. Nonetheless, the evidence we have collected suggests that Lexipol’s policies and trainings may differ in meaningful ways from those proposed by policing experts and researchers and that Lexipol’s focus on liability risk management may explain at least some of those differences.

B. Secret Policymaking

Proponents of police reform have long recommended that police policies be created through a transparent, quasi-administrative process. Beginning in the 1950s and 1960s, commentators advocated for an administrative rulemaking process whereby proposed policies would be subject to notice and comment by the public.[205] As President Johnson’s 1967 Commission explained, “the people who will be affected by these decisions—the public—have a right to be apprised in advance, rather than ex post facto, what police policy is.”[206] Ideally, policies would also be evaluated after enactment by law enforcement officials, researchers, and the public.[207]

Today, scholars are again calling for an administrative rulemaking process that encourages police to develop detailed policies that are subject to notice and comment and some manner of judicial review.[208] Contemporary commentators have also emphasized—perhaps even more forcefully than their predecessors—that any administrative police rulemaking process should directly engage community members and that policies should be tailored to the particular circumstances and interests of the community.[209] Advocates for these more democratic processes contend that they can lead to more effective policies and enhance the perceived legitimacy of policing.[210] Increasingly, police departments are incorporating these democratic ideals into their policymaking processes: In 2015, several law enforcement leaders signed on to a Statement of Democratic Principles, organized by New York University (NYU) School of Law’s Policing Project, which included a commitment to a rulemaking process that incorporates robust community engagement.[211]

Lexipol’s policymaking process departs considerably from the transparent, quasi-administrative policymaking processes recommended by scholars and policing experts and adopted by some law enforcement agencies. Instead of policies crafted locally and with community input, policies created by Lexipol are based on a uniform state template. Lexipol’s standardization of policymaking is one of the reasons that the private service has been so commercially successful. But its approach runs contrary to that recommended by experts and embraced by some law enforcement agencies.

Lexipol does not preclude local jurisdictions from seeking out the types of community engagement and deliberation that scholars and experts recommend, or tailoring Lexipol policies to reflect local values and interests. In this Article, we have not examined the extent to which local jurisdictions modify Lexipol’s standard policies to reflect local values and interests, or whether jurisdictions are engaging community members in the customization process.[212] But several aspects of Lexipol’s structure make us wary of simply assuming that jurisdictions will seek public input or modify policies based on their own needs once they have made the decision to give the policymaking job to Lexipol. First, Lexipol provides local jurisdictions with little information about the reasons for its policy choices, which makes it difficult for subscribers to make informed decisions about whether to adopt Lexipol’s policies. Lexipol’s statewide master manual does identify whether a policy is required by law, a best practice, or discretionary.[213] But the manual contains no explanation of what evidence Lexipol considers when designing its policies, why Lexipol makes particular drafting decisions, or whether there are other plausible alternative policies.

The other materials Lexipol provides to its customers are similarly unilluminating. We used the Public Records Act to request all information that the California agencies had regarding their relationship with Lexipol. What we typically obtained was Lexipol’s standard police manual, a contract, and evidence of payment. Many jurisdictions also had marketing information that they received from Lexipol, e-mail exchanges, and PowerPoint presentations from Lexipol executives. Some had internal memoranda justifying local jurisdictions’ decisions to purchase Lexipol’s service rather than continue to write their own policy manuals. Some had materials from Lexipol that described amended policies and the rationale for the amendments (generally a change in the law). But none of the departments produced materials from Lexipol that described the evidentiary basis for policies, drafting decisions by the company, or the existence of alternative approaches.

The Lexipol executives with whom we spoke reported that, since 2008, jurisdictions have also had access to policy guides that offer general background information about policies. Yet the fact that no jurisdictions provided us with such guides—and a detective from one jurisdiction, when asked about the policy guide, said he had never seen or heard of it—confirms one Lexipol vice president’s view that these guides are “well-kept secrets” and difficult for departments to access online.[214] Moreover, we are skeptical that these guides—even if widely available—would provide much information to agencies about Lexipol’s policy decisions. Lexipol declined to provide us with a copy of its policy guide, but it did provide us with a single page of the guide regarding body camera video, and that page provided little basis by which a Lexipol customer could assess the sensibility of Lexipol’s policy choices in this area.[215]

Even when local jurisdictions seek out information from Lexipol about the bases for its policy-drafting decisions, Lexipol reveals scant information about its choices. For example, a sergeant at the Irvine Police Department e-mailed Lexipol, seeking information about several aspects of Lexipol’s use of force policy, including:

- Where did the definition of Force come from? Has it changed over time? I know there is not one agreed upon definition as it applies to UoF policy, but was wondering where your definition came from.

- Is the lethal force policy verbiage based on federal standards? It varies slightly from ours, primarily because it includes the word imminent. The definition of imminent is broadly defined to include preventing a crime. Was the Lexipol wording derived from case law that includes “imminent” as it is defined in your policy?[216]

The sergeant explained in his message that the Irvine Police Department has its own policy manual but uses Lexipol to “augment” its policies, and that he was reviewing Lexipol’s policies to see whether and how they should adjust their own manual.[217] The Lexipol representative responded quickly to the sergeant’s questions but offered no specifics about its use of force policy choices, writing only: “The force definitions are based on federal guidelines as well as the deadly force section. This policy has changed over time with the changes in laws and case decisions. The ‘imminent’ wording again is based on the federal guidelines.”[218] Although the sergeant took this laudable step to discover additional information about Lexipol’s standardized policy, the company offered him minimal guidance.

Our research uncovered similar concerns regarding the claims that Lexipol makes about its DTB trainings. Although Lexipol promises that its two-minute trainings and “every day is training day” philosophy will save subscribers money and reduce exposure to lawsuits, we found no empirical support for these claims. Indeed, citing a litany of concerns, California’s Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) twice declined to certify Lexipol’s DTBs as sufficient to satisfy their minimum standards for state law enforcement training.[219] Among other concerns, the Commission cited a “[l]ack of evidence or feedback to indicate the information [in Lexipol’s DTBs] is understood or can be applied.”[220] According to the Commission staff, the true/false format of the extremely brief DTBs provides no “proof of learning” or “degree of assurance that the information would be applied in a unique situation, i.e., beyond the single scenario included in the DTB.”[221] Moreover, the DTBs do not include clear “learning objectives,” do not ensure that students will actually read the information contained in the DTBs, are entirely “stand-alone trainings” not supported by “the assistance or guidance of an instructor,” and fail to provide opportunities for “practice or feedback.”[222] The fact that the DTBs are “part of a wholly proprietary subscription service” and distributed by a “private, for-profit company” also weighed heavily in the Commission’s decision to decline certification of the trainings.[223] In particular, the Commission found it troubling that it would have no “oversight” over Lexipol’s privatized “content, instructional methodology, instructor competence, or effectiveness” and that non-subscribing agencies would not have access to the proprietary, fee-based trainings.[224]

In sum, based on the information we have been able to collect, we do not believe that Lexipol provides subscribing agencies with sufficient information for them to be able to understand what evidence Lexipol has consulted when crafting its policies and trainings, the rationale for its drafting decisions, or whether there are diverging opinions about best practices in a given area. Even if a jurisdiction tries to deviate from the standard-issue Lexipol policies or trainings, it must address structural aspects of Lexipol’s products that make it burdensome to customize. For example, Lexipol’s update service automatically overrides client customization. The Lexipol policy manual updates repeatedly caution subscribers that “[e]ach time you accept an update the new content will automatically replace your current content for that section/subsection of your manual,” meaning that “if you have customized the section/subsection being updated you will lose your specific changes.”[225] The fact that Lexipol’s DTB trainings are all based on the standard policies is another impediment to customization. Jurisdictions wishing to deviate from Lexipol’s standard trainings would need to invest in creating their own training programs.

Finally, Lexipol’s subscribers purchase Lexipol’s products in part because they do not have the money or time to engage in their own rulemaking processes. Lexipol markets its service as a cost-saving tool, emphasizing that it costs less to adopt the Lexipol manual than to pay internal staff to research and develop policies on their own. And Lexipol subscribers applaud the service because it eliminates the need for police chiefs and other government officials to develop policies themselves.[226] If a subscriber wanted to modify Lexipol’s standard policies, it would need to identify alternative policy language, consider the strengths and limitations of that alternative, and seek community input. Most jurisdictions that contract with Lexipol are unlikely to dedicate the time and money necessary to this project, particularly given Lexipol’s assurances that its policies reduce litigation and litigation costs so dramatically.

In this Article, we do not examine the substance of Lexipol’s policies or compare its policies to those created through the transparent, quasi-administrative processes recommended by scholars and experts and adopted by some progressive agencies. But we defer to their view that there are democratic and perhaps substantive benefits to customization and community engagement in police policymaking. We are concerned that Lexipol’s lack of transparency about its policy decisions, the difficulty of modifying Lexipol’s manual, and the financial pressures faced by agencies that decide to purchase Lexipol’s services discourage local agencies from evaluating the sensibility of Lexipol’s policy choices, seeking community input, or modifying policies to reflect local priorities.

C. Policymaking for Profit

Those who have promoted police policymaking over the past several decades never considered the possibility that a private, for-profit enterprise might play such a dominant role in the creation and dissemination of police policies. Yet perhaps the rise of Lexipol should come as no surprise. Private entities have long engaged in police functions.[227] Private companies have also drafted government policies, standards, and regulations.[228] And more generally, private–public partnerships and hybrids have become the rule, rather than the exception.[229] The growth of Lexipol and other private agencies involved in police policymaking is consistent with the privatization of law enforcement functions and the increasing privatization of government policies, standards, and regulation more generally.

Privatization scholars tend, in varying degrees, to applaud privatization as more effective and efficient than government action and to despair that privatization compromises democratic principles.[230] Our study of Lexipol offers evidence to support both views. In this Article, we have not compared Lexipol’s policies with those drafted by agencies and so cannot reach any firm conclusions about whether Lexipol’s policies are more “effective”—by whatever metric one might use—than policies drafted by local agencies. But Lexipol subscribers quoted on Lexipol’s website appear to believe that the company’s policies are of higher quality than they could create on their own.[231] Lexipol’s dramatic expansion over the past fifteen years suggests a widespread belief that the company is better situated than local law enforcement agencies to perform the police policymaking function and can do so at reduced cost.

Yet our study of Lexipol also offers anecdotal support for common criticisms of privatization. As we have argued, Lexipol appears to prioritize liability risk management over other interests, and the secrecy with which it drafts its policies makes it difficult for law enforcement to understand the bases for Lexipol’s policy decisions. These observations echo concerns by privatization scholars that private companies overvalue efficiency interests and lack transparency.[232] In addition, Lexipol’s interest in making a profit creates unorthodox relationships between the policymaking company and the public police agencies that subscribe to its services.

For example, Lexipol’s standard contract with subscribers contains an indemnification clause providing that the company “shall have no responsibility or liability” to any subscriber for its products.[233] According to Lexipol, an indemnification term is necessitated by its business model: As Lexipol explained in a memorandum to customers, removing the indemnification clause would mean that subscription prices would increase “dramatically” to account for the possibility of litigation.[234] Nevertheless, Lexipol has also assured its subscribers that “Lexipol’s content has been published for agency use for over 10 years,” and “[w]e are unaware of any case in which Lexipol provided content was found faulty by a court. . . . Consider that track record against any alternative.”[235]

Although Lexipol’s indemnification clause may make business sense for the company and for its subscribers, it creates the potential for a liability shell game when policies are faulty. A plaintiff can sue a city or county if she suffered a constitutional harm that resulted from official police policy.[236] Presumably as a means of avoiding liability under this legal theory, Lexipol has repeatedly made clear that “Lexipol will never assume the position as any agency’s ‘policy-maker.’”[237] In negotiations with one jurisdiction over the indemnification issue, Lexipol offered the curious rationale that it only “suggests” content and does not actually “control” the policies adopted by the agency:

We only suggest content. The agency has total control of their actual policies. The Chief will adopt the Policy Manual before it is deployed and certify that he is the Policy Maker as defined by federal requirements. Certainly the agency would not ask us to indemnify what we do not control.[238]

In addition, when Lexipol issues a policy update, it cautions its subscribers “to carefully review all content and updates for applicability to your agency, and check with your agency’s legal advisor for appropriate legal review before changing or adopting any policy.”[239] These disclaimers about Lexipol’s policymaking role sit in stark contrast with the broader messaging by Lexipol to jurisdictions—that its policies are “legally defensible” and designed to help jurisdictions avoid litigation that will result from out-of-date policies. Indeed Lexipol markets its policies as a cost-savings because agencies can adopt them without modification.[240]

Lexipol, LLC’s vigorous use of copyright law to protect its business interests is another troubling outgrowth of its for-profit status. Under a standard term found in all Lexipol contracts, Lexipol, rather than the contracting agency, holds the copyright to all policies.[241] Even when a law enforcement agency that contracts with Lexipol amends Lexipol’s model policies, Lexipol regards the resulting amended policy as covered by Lexipol’s copyright.[242] The manuals used by Lexipol subscribers have the Lexipol copyright on each page, even when the subscriber has added original content to the page.[243]

Lexipol has a sensible business argument for copyrighting its policies and preventing its policies from being adopted by other agencies without paying Lexipol. As Lexipol’s CEO explained in correspondence to a customer in our study, “if we do not correct/defend any and all known violations we risk losing the copyright and by extension we risk our ability to do business.”[244] Yet this copyright position may inhibit improvements to Lexipol’s policies and stunt development of policies and best practices more generally.

Police policymaking is often viewed as a collective enterprise among advocacy groups, community leaders, and other experts. For example, the Immigrant Legal Resource Center (ILRC), a nonprofit organization that advocates for the rights of immigrants, has published a guide featuring policies from several jurisdictions that protect immigrants from federal immigration enforcement.[245] As part of this project, ILRC also publishes an interactive national map that includes links to local policing policies that disentangle local law enforcement from federal deportation efforts.[246] Campaign Zero, a nonprofit organization dedicated to ending police-caused deaths, has crafted a model use of force policy from components of policies adopted by departments in a number of jurisdictions including Philadelphia, Denver, Seattle, Cleveland, New York City, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, and Milwaukee, all of which are made available to the public on Campaign Zero’s web page.[247]

The basic idea behind these efforts is that sharing, evaluating, and modifying policies from different jurisdictions will improve police policies overall. Groups like ILRC and Campaign Zero can identify the strengths and weaknesses of policies from different jurisdictions and analyze the ways in which these policies impact discretionary decisionmaking. This information can then be used by other jurisdictions to make informed decisions about which policies to adopt.

Lexipol’s copyrighted policies can only play a limited role in this evaluative process. Lexipol subscribers can make their policies public and sometimes post their policies online.[248] But Lexipol’s copyright stamp must be included on each page of those policies. And it is Lexipol’s position that other jurisdictions cannot adopt language from Lexipol policies—even policies that have been modified by their subscribers—without first paying Lexipol. When Lexipol learned that the Tustin Police Department—a Lexipol subscriber—did not have a Lexipol copyright stamp on its policy manual’s pages and had distributed its manual online and shared portions of its manual with other agencies, then-CEO Ron Wilkerson contacted the Tustin Police Chief with the company’s copyright concerns. Wilkerson explained to the chief that “if your manual is posted on any web site or forum such as the [International Association of Chiefs of Police] site and others use that content not knowing it is copyrighted material a much more serious problem takes shape.”[249] Wilkerson also asked that the chief identify any agencies that might be using the policies so that he could “work to correct the problem.”[250] Lexipol’s approach allows the company to preserve its copyright and the associated financial benefits but is contrary to a collaborative policymaking approach.