Interpreting by the Rules

A promising new school of statutory interpretation has emerged that tries to wed the work of Congress with that of the courts by tying interpretation to congressional process. The primary challenge to this process-based interpretive approach is the difficulty in reconstructing the legislative process. Scholars have proposed leveraging Congress’s procedural frameworks and rules as reliable heuristics to that end. This Article starts from that premise but will add wrinkles to it. The complications stem from the fact that each rule is adopted for distinct reasons and is applied differently across contexts. As investigation into these particularities proceeds, it becomes apparent that the complications are also rooted in something deeper—that Congress’s procedures are often hollow, even fraudulent. Congress, it turns out, breaks its own rules with impunity.

Which brings us to a deeper riddle: What is the significance of the rules to an interpreter when Congress routinely flouts them? If one’s goal is to accurately depict the lawmaking process in hopes of deriving rules of construction that have democratic roots, then surely the interpreter must discard the rules as hopelessly unreliable guideposts. Then again, if the interpreter’s ultimate aim is to serve democratic ends, then shouldn’t we strive toward rule of law values, ensuring that Congress acts in an honorable way? Ultimately, I resolve the question by first asking what the rules are meant to do. Only then can we understand what it means to interpret by them. Through examination of many procedural contexts, I set forth an innocuous account of congressional defiance of the rules. Rather than a symptom of branch dysfunction, we should see the rules as guidelines that attempt to order congressional business but that ultimately must give way to politics. Nonetheless, some rules can help the interpreter paint a more faithful picture of congressional procedure in spite of their not being followed. More broadly, I conclude that interpretive presumptions deriving from the general efficacy of legislative rules, rather than their precise enforcement, are more successful in mirroring congressional reality.

Introduction

In a sense, we students and scholars of statutory interpretation are all formalists. We strive to arrive at some ordered set of principles from which we can derive meaning from a statute. To this end, a promising new school of statutory interpretation has emerged that tries to wed the work of Congress with that of the courts.[1] It does so by linking rules of interpretation to Congress. The payoff is twofold. If those who write the laws and those who interpret them get on the same page, we can finally achieve a coordinating system of efficient and objective rules. Better yet, the link to Congress ensures that this particular brand of formalism has democratic legitimacy.

This new “process-based”[2] school of interpretation has already influenced federal judges, who have begun to adapt their interpretive approaches to reflect new empirical work on the congressional process.[3] This empirical work offers a response to textualists who have long argued that Congress is simply too irrational and too complex for judges to understand. Armed with research, it is, in fact, possible to understand how Congress works. All that is needed is careful study of it.

The process-based scholars have, for instance, studied modern developments in congressional process. Legislative paths like the reconciliation process complicate the traditional story of how a bill becomes a law. The rushed manner in which Congress passes reconciliation bills, they argue, should lead us to posit that Congress is not drafting with precision in that context.[4] A judge must take this into account in deciding how much interpretive slack to give to Congress when it enacts “unorthodox” legislation.[5]

Surveys of staffers have turned up inconsistencies between old canons of construction and legislative reality. Because congressional committees are siloed, for instance, the consistent usage canon should have no bearing in interpreting omnibus legislation, the parts of which have originated in different committees.[6] And because staffers do not use dictionaries when drafting statutes, an interpreter’s reliance upon them is misguided.[7]

These scholars have also developed canons of construction that derive from Congress’s procedural frameworks, a strain of the literature that is the primary focus of this Article.[8] In early work, I myself argued that courts have the unique ability to leverage congressional transparency by interpreting legislation in accordance with legislative rules that are aimed at unearthing hidden special interest deals.[9] Later scholars have gone further to use legislative rules more generally in the interpretive process.[10]

This rules-based strain holds particular promise to process-based interpretation. If the primary challenge to this interpretive approach is the difficulty in reconstructing congressional process, then discovering reliable heuristics to that end may broaden the new school’s reach. The prescription seems simple enough. If we look to ways in which Congress governs itself, paying particular attention to its enumerated rules, we can better understand the congressional process and hence its output.

This Article starts from that premise but will add wrinkles to it—so many, in fact, that the interpreter may at times be left only with a sow’s ear. The complications stem from the fact that each rule is adopted for distinct reasons and is applied differently across contexts. It may, for example, be prudent to assume Congress’s transparency rules are working as intended; other rules may cause us more trouble.

As our investigation into these particularities proceeds, we will begin to see that the complications are also rooted in something deeper—that Congress’s procedures are often hollow, even fraudulent. Congress, it turns out, breaks its own rules with impunity.

Which brings us to a deeper riddle: What is the significance of the rules to an interpreter when Congress routinely flouts them? If one’s goal is to accurately depict the lawmaking process in hopes of deriving rules of construction that have democratic roots, then surely the interpreter must discard the rules as hopelessly unreliable guideposts.

Then again, if the interpreter’s ultimate aim is to serve democratic ends, then shouldn’t we strive toward rule of law values, ensuring that Congress acts in an honorable way? If so, then ignoring Congress’s deliberate violation of its rules in the interpretive process creates a mechanism to punish Congress when it does so. The counterfactual assumption may serve to help repair the “broken branch.”

This interpretive conundrum defies traditional separation of powers analysis by forcing us to confront many overlapping inquiries and feedback loops. Ultimately, I resolve the question by first asking what the rules are meant to do. Only then can we understand what it means to interpret by them. Through examination of many procedural contexts, I set forth an innocuous account of congressional defiance of the rules. Rather than a symptom of branch dysfunction, we should see the rules as guidelines that attempt to order congressional business but that ultimately must give way to politics. The rules, in other words, are made to be broken.

The judiciary, of course, must generally defer to politics if separation of powers is to mean anything. The Rulemaking Clause in the Constitution contemplates this arrangement, which prohibits the judiciary from enforcing legislative rules against Congress.[11] So fundamental is the legislative power over its rules that it could be argued the Clause is superfluous; that generally accepted separation of powers principles would force us to arrive at the same result.[12]

Having discarded the normative argument that the judiciary should improve congressional process by taking seriously congressional rules, does that mean the interpreter should abandon them altogether? To this, we must return to the descriptive and ask if they ever bring us closer to understanding congressional reality. The answer depends on the legislative rule and context in question. At times the rules may bear fruit; other times they may not. Some rules can help paint a more faithful picture of congressional procedure in spite of their not being followed. Ultimately, I conclude that interpretive presumptions deriving from the efficacy of legislative rules, rather than their precise enforcement, are more successful in mirroring congressional reality.

A deep dive into the weeds of congressional procedure is necessary to begin to understand what the rules can tell us. In so doing, I aim to lay the groundwork for an interpretive endeavor that serves to refine the process-based approach by crafting a more nuanced picture of congressional reality.

Such an approach preserves the ability of judges to rely confidently on fundamental aspects of the legislative process that are unlikely to change. Two of the process-based school’s leading lights, Abbe Gluck and Lisa Bressman, have noted that “[a]ny empirically grounded theory of interpretation will face th[e] problem of keeping up with changing circumstances.”[13] This danger is not as prevalent with essential features of the legislative process, such as the prioritization of committee reports and the fast and loose nature of the reconciliation process, since those attributes are unlikely to change. Congressional adherence to legislative rules, however, is constantly evolving due to their nature as endogenous devices. Although at any given time, the congressional process may appear to be heavily influenced by a rule, this will change under different circumstances. The interpreter must be attuned to this dynamic.

Others have critiqued the new interpretive school by invoking traditional textualist arguments.[14] This Article contributes to the literature by instead assessing process-based interpretation, which is predicated on judicial understanding of the legislative process, on its own terms. It is my view that the process-based school creates a mechanism that sheds light on legislative priorities. For the judiciary to ignore the realities of the increasingly complex legislative atmosphere risks burying those priorities. But through examination of the many twists and turns the legislative process can take, we can see just how complex it is. Interpretation based on strict adherence to rules or some other simplistic proxy may very well lead the interpreter astray. Instead, the judiciary should pursue a more contextualized approach to process-based interpretation that better reflects legislative realities. So into the weeds we must go.

* * *

Part I of this Article provides background on the new process-based school of interpretation, as well as critiques that have been lodged against it. Part II discusses features of the legislative process, particularly those relating to legislative rules, and the ways in which they depart from the assumptions underlying some of the new school’s recommendations. Part III argues that normative considerations mitigate against wholesale importation of Congress’s rules into the interpretive project. Part IV offers a view of what process-based interpretation should look like, in light of the above concerns and observations.

I. Background

The rise of the process-based school of interpretation has been steep over the past decade, but it has roots in earlier scholarly work. This Part traces that trajectory before turning to modern critiques of the school.

A. The New Process-Based School of Interpretation

A number of scholars have attempted to improve the interpretive endeavor by introducing insight into the legislative process. The early scholars focused largely on how lawmakers used legislative history. Chancellor Nicholas Zeppos recommended that judges engage in a fact-finding model of statutory interpretation, examining for instance the degree of exposure that a piece of legislative history had among lawmakers.[15] Professors Daniel Rodriguez and Barry Weingast leveraged positive political theory to identify pivotal lawmakers and the legislative history generated by them as particularly important in the interpretive process.[16]

In an early example of the empirical turn in the literature, Professors Victoria Nourse and Jane Schacter conducted a case study of legislative drafting in the Senate Judiciary Committee.[17] Their findings illustrated that drafters do not systematically comport with judicial views of statutory interpretation.[18] For instance, despite Scalia’s powerful critique of legislative history, the committee continued to write congressional understandings of the legislation.[19] The Nourse/Schacter study also explored other issues, such as the lack of influence of canons upon the drafting process,[20] the influential role of lobbyists in drafting the text of bills,[21] and the heterogenous nature of drafting practices.[22]

More recently, Victoria Nourse has argued that interpretation of statutes should hinge on congressional rules.[23] Nourse reasons that legislative history can only be understood against the backdrop of legislative rules. In her view, the rules can be used to separate the “wheat from the chaff of legislative history.”[24] For textualists, the rules can identify which texts are central in cases of conflict.[25]

Nourse argues for a presumption that Congress not only knows but also follows its legislative rules.[26] For example, Nourse argues that Public Citizen v. U.S. Department of Justice,[27] a notoriously difficult statutory interpretation case, could have been easily resolved by following the legislative rule that conference committees do not have authority over matters where the House and Senate are in agreement.[28] Similarly, Nourse contends that the Supreme Court’s opinion in TVA v. Hill[29] overlooked congressional rules that forbid legislative text on appropriations.[30]

Most notable among scholars representing the modern process-based school of interpretation, Professors Gluck and Bressman surveyed 137 staffers involved in legislative drafting, posing 171 questions that seek to explore the interpretive responsibilities of courts and agencies and detailing their findings in two articles.[31] In undertaking this ambitious project, Gluck and Bressman seek to corroborate or discredit the assumptions about drafting that undergird the theories and practice of statutory interpretation.[32] For instance, they suggest certain items in the textualist’s arsenal are not supported by congressional reality.

Most relevant for our purposes, in response to their survey, many staff highlighted the importance of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) score in drafting the statute.[33] Specifically, staff revise legislation in response to CBO’s comments on draft bills so that budget targets are met. From this, Gluck and Bressman recommended a CBO canon,[34] which Gluck developed in other work.[35]

Finally, in a recent book, Judge Robert Katzmann forcefully argues that judges must understand the institutional dynamics of Congress in their interpretation of statutes. In Katzmann’s view, “understanding [the legislative] process is essential if it is to construe statutes in a manner faithful to legislative meaning.”[36] Katzmann draws upon the work of Nourse and Schacter, as well as Gluck and Bressman, in painting a picture of the legislative process that may be surprising to most textualist judges. He emphasizes the heterogeneity of drafting practices, that legislation is drafted by staff, not members, and done so in alignment with the members’ policy preferences, and the heavy reliance by members on committee reports.[37] He also notes the findings of others that canons are of little use to drafters, that they do not use dictionaries, nor do they seek coherence within or across statutes.[38] Stemming out of these observations, Katzmann recommends that judges deemphasize some canons and use legislative history to the extent the legislators gave it priority.[39]

B. Critiques of the Process-Based School

The rise of the process-based school has not gone unchallenged. Notable critiques have come from Professor John Manning and Justice Amy Barrett, both grounding their views in textualism. I discuss their views below.

1. Intent Skepticism

Professor Manning’s account of the process-based school is that it simply has nothing to offer to those interpretive theories that are skeptical of legislative intent. He posits that although Gluck and Bressman do not explicitly align themselves with intentionalism, they rely upon the subjective intent of the drafters in criticizing prior interpretive methods and justifying new ones.[40] Yet in Manning’s view, the authors’ findings do not undermine the inherent indeterminacy of legislative intent nor do they obviate the need for a normative frame of reference in making sense of such intent.[41]

To illustrate, Manning canvasses various approaches to statutory interpretation and how they manifest what he labels “intent skepticism.” Textualists, for instance, argue that social choice theory illustrates that lawmakers may “cycle endlessly” their intransitive preferences and that “intent” of the majority therefore depends on arbitrary factors such as the order upon which policies were voted.[42] Another of their claims is that the legislative process is simply too complex for judges to replicate.[43]

But the intent skepticism is not just confined to textualists, according to Manning. Legal realists assert that judges engage in policymaking when deciding cases and will not attempt to unearth the intentions of hundreds of legislators.[44] Pragmatists also express doubt about discerning legislative intent, given the number of actors involved and the limitations of the historical record, instead prescribing pragmatic reasoning to decide statutory cases.[45] Dworkinians would posit that vexing questions over whose intention should count and the need for aggregating intent make the whole endeavor arbitrary.[46] Finally, according to Manning, even Legal Process scholars are intent skeptics who urge a pursuit of a reasonable purpose rather than actual legislative intent.[47] In Manning’s view, these theories leave room for inserting normative views about the system of government into the interpreting process, having freed the interpreter from making a factual inquiry into congressional intent.[48]

Having discussed the older theories of statutory interpretation, Manning then turns to the process-based scholars, who have in various ways proposed methods of discovering Congress’s actual decision-making through gathering evidence about how Congress works. Manning argues that these new scholars align themselves with classic intentionalists but that their findings do not obviate the arguments of the intent skeptics.[49] No matter how well we know the minds of lawmakers, Manning contends, we still must make value judgments in making attributions to Congress.[50]

Manning argues that even though staff may be unaware of common tools of statutory interpretation, this does not render them objectionable. Such “off-the-rack rules” may enable Congress to express itself, regardless of whether the drafters intentionally have followed them.[51] As Gluck and Bressman point out, today’s Congress legislates through unorthodox lawmaking that involves multiple committees, thus rendering consistent-usage canons like the whole act rule suspect.[52] And today’s staffers do not consult dictionaries when they are drafting statutes.[53] In Manning’s view, these findings only reinforce the notion that Congress does not resolve interpretive questions at a granular level. Instead, we must look to conceptions of legislative supremacy or faithful agency to fill in the gaps.[54]

Gluck and Bressman also rely on their survey to question textualist objections to legislative history. In Manning’s view, this is also problematic because whether legislative history constitutes legislative intent is a normative question.[55] Why, after all, should we defer to the technical product of unelected Legislative Counsel rather than the product upon which Congress itself chooses to vote?[56] In other words, Gluck and Bressman’s empirical work “force[s] us to reckon with the fact that there is no way to derive legislative intent from the brute facts of the legislative process,”[57] thereby confirming intent skepticism rather than quelling it.

2. Congressional “Insiders” Versus “Outsiders”

Justice Barrett argues that the new process-based statutory interpretation scholars incorrectly assume that statutory interpretation theorists endeavor to reflect the actual practices of the drafters.[58] Barrett contends instead that this misses the mission of textualism entirely. Whereas the process-based scholars are focused on “congressional insiders” or hypothetical legislators in their approach to language, textualists emphasize the importance of “congressional outsiders” or the ordinary readers of statutory text.[59]

Barrett contends that this divide can be explained by different conceptions of faithful agency. Textualists, in her view, are agents of the people, whereas the process-based scholars are agents of Congress. Textualists are therefore bound to the most ordinary meaning of the statute since that is how their principal interprets them.[60]

Barrett emphasizes that the process-based theorists themselves rely on statutory text above all else and thus are influenced by textualists. And, unlike Manning, she takes Gluck and Bressman at their word—that they are also intent skeptics.[61] It is at this point, however, that the textualists and process-based theorists diverge. If both discard actual legislative intent, the textualist constructs objective intent based on an ordinary reader. A process-based theorist bases objective intent on the experience of a hypothetical lawmaker.[62]

Using this view of faithful agency, Barrett contends that the textualists’ predilection for dictionaries and canons is not undermined by evidence that Congress rejects them but would only be thwarted by evidence that the canons do not track common usage.[63] Barrett extends this reasoning to legislative history. Professor Nourse proposes that courts should interpret in accordance with legislative rules because this is how a typical lawmaker would have understood the language.[64] A textualist, according to Barrett, would reject this endeavor as failing to reflect how an ordinary person would read the statute—congressional practice be damned.[65]

3. The Conversation Model of Interpretation

In a vein similar to Professor Barrett’s, Professor Doerfler argues that insights from the philosophy of language necessitate viewing the law as a conversation between lawmakers and administers of the law (courts and agencies) or lawmakers and objects of the law (citizens).[66] In contrast, a process-based model of interpretation erroneously treats the law as being written for lawmakers by other lawmakers. This is because it focuses on the legislative process, of which lawmakers are acutely aware but citizens are deeply ignorant.[67] In Doerfler’s view, it is wholly irrelevant that committee reports are more salient to staffers than floor statements since ordinary citizens do not understand the distinction between the two.[68]

4. Situating the Project

On the following pages, I will complicate understandings of the legislative process upon which some of the process-based scholars’ recommendations are based. In doing so, I do not seek to undermine their endeavor but rather to elevate it through refinement, on its own terms of congressional understanding. Some of my conclusions may be taken to further the view of the textualists and others that the legislative process is simply too messy for judicial understanding.[69] That is not my intention. I have greater faith in a judge’s ability to accompany me in the weeds, as I will later discuss.

II. Congressional Rules and Reality

A. Legislative Rules

1. Background

Before exploring the ways in which Congress deviates from its rules, it is helpful to understand their constitutional status and Congress’s general mode of enforcement. Each house enacts its own set of legislative rules, primarily through its standing rules. The House adopts its standing rules at the beginning of each Congress, largely adhering to the prior rules with some amendments.[70] The standing rules of the Senate are in force until they are revised because the Senate has traditionally been viewed as a “continuing body,” meaning it continues to exist after an election cycle because only one third of its members face reelection each cycle (in contrast to the House, where all of its members are up for reelection every two years).[71]

Some legislative rules are adopted outside the standing rules. For instance, rules governing the budget process are sometimes set forth in the budget resolution.[72] Others are even codified in statutes.[73] Despite the fact that they are not formally incorporated into the standing rules, these rules are not different in kind.

In addition to the rules, each house also collects a rich body of precedential rulings, which have varying, and sometimes mysterious, degrees of authority.[74] In the Senate, for instance, the most forceful precedents are those that the entire Senate body has weighed in on.[75] Some precedents may even take priority over the standing rules.[76]

The Constitution generally imposes few restraints upon the legislative process. Article I, Section Five, Clause Two authorizes each house to “determine the Rules of its Proceedings.”[77] In addition to creating its rules, as a constitutional matter, each house may change them without action by the other house.[78] This is almost certainly the case even when Congress enacts internal rules through statutes. Although statutes require passage by the other house, as well as the President’s signature to become law, the Rulemaking Clause likely requires that they be voidable by one chamber.[79]

Importantly for our purposes, the hallmark of legislative rules is flexibility. Each house can make, amend, repeal, suspend, ignore, or waive their legislative rules.[80] Each can also choose from several different procedural frameworks in passing laws.[81]

This flexibility also extends towards the rules’ enforcement, which is wholly internal to Congress. A member of Congress can only enforce a rule violation by making a point of order.[82] In the House, the Speaker and the Chairman of the Committee rule on all points of order, which can be overruled by the body on appeal, usually by a two-thirds vote.[83] Senators who have submitted points of order may demand a Senate vote.[84] Rules can be waived or suspended in the Senate, however, by unanimous consent agreements.[85]

Congressional power over the internal rules stems from not only the Rulemaking Clause but Congress’s inherent lawmaking authority as well. Justice Story described this inherent authority as follows:

No person can doubt the propriety of the provision authorizing each house to determine the rules of its own proceedings. If the power did not exist, it would be utterly impracticable to transact the business of the nation, either at all, or at least with decency, deliberation, and order. The humblest assembly of men is understood to possess this power; and it would be absurd to deprive the councils of the nation of a like authority.[86]

The legislature’s control over its internal processes can be traced to the British theory of legislative sovereignty, which was erected to counter the monarchy.[87] Perhaps because of its strong historical roots, the Framers adopted the Rulemaking Clause without any deliberation.[88]

Separation of powers principles thus suggest the Clause may, in fact, be superfluous. This conclusion receives support from the fact that the Constitution’s predecessor, the Articles of Confederation, had no such clause and yet the Continental Congress had purview over its legislative rules.[89] To be sure, the Constitution does place some limitations on the lawmaking process, which the judiciary can enforce. For instance, Article I prescribes rules for legislative assembly, selection of officers, discipline of members, and voting and quorum rules, among others. Article I, Section Seven also prescribes the “single, finely wrought and exhaustively considered, procedure” for enacting or repealing law.[90]

Even still, Article I, Section Seven leaves most of the process details to Congress, apart from bicameralism and presentment.[91] For instance, the Constitution is silent as to whether an identical bill must be passed by each house, instead leaving Congress to designate how to agree on a bill that is presented to the President.[92] The Constitution is also silent on the manner of passage. Under current legislative rules, a bill can pass with only one member of the majority present, and there is no requirement that a legislator know the contents of the bill before a vote.[93]

2. Examples of Rules and Deviations

The above framework illustrates that legislative rules are endogenous to Congress and Congress may do with them what they wish. They can be ignored, waived, amended, etc. The rest of this section will explore a few examples of legislative rules, how they have been used in the case law, and how Congress actually interprets, enforces, and deviates from them.

a. The Prohibition Against Lawmaking Through Appropriations.—Two types of legislation are: authorizing legislation, which creates or modifies a government activity or program; and appropriations, which provides funding for the activity or program.[94] Longstanding congressional rules and practice erected this distinction.[95] In the 1800s, appropriations began to be delayed because of debates over substantive legislation. In 1837, the House addressed this problem by adopting a rule that prohibited appropriations from being reported on authorizing legislation if not previously authorized.[96] Other legislative rules maintain the separation between the categories, although, as will be discussed, the distinction is increasingly blurred. Current House Rule XXI(2) and Senate Rule XVI(4) prohibit appropriations from changing existing law.[97] The principle embodied by these rules is sometimes invoked by courts in the course of interpreting statues.

In an 1886 case, U.S. v. Langston,[98] for instance, the Supreme Court deployed the rule against changes to substantive law via the appropriations process in construing whether a statute prescribing the salary of a public officer could be modified or repealed by subsequent appropriations of a lesser amount.[99] Although the Supreme Court did not explicitly rely on an underlying legislative rule prohibiting substantive changes via appropriations, it may have been inspired by congressional practice.

The Court was explicit in its reliance on the rules in a well-known 1978 statutory interpretation case, TVA v. Hill, when it considered whether subsequent appropriations measures that funded the construction of a dam violated the Endangered Species Act.[100] The Court held that the appropriations could not be used for an otherwise unlawful purpose, in part reasoning that congressional rules supported this result.[101] The Court specifically cited to House Rule XXI(2) and Senate Rule XVI(4) and noted that an opposite ruling would “assume that Congress meant to repeal [a part of the Endangered Species Act] by means of a procedure expressly prohibited under the rules of Congress.”[102] Other lower courts have adopted an interpretive rule against changes to substantive law via the appropriations process without explicitly relying upon the relevant legislative rules.[103]

Both the Supreme Court and lower courts, however, have decided not to follow this rule when the amendment or repeal of the substantive law is clear.[104] One of these cases is worth discussing in detail. In Roe v. Casey,[105] the Third Circuit held that the Hyde Amendment in an appropriations bill modified a Medicaid statute requiring participating states to fund abortions that receive federal reimbursement.[106] The court noted that the House of Representatives waived all points of order raised against the Hyde Amendment for failure to comply with House Rule XXI(2).[107] The court rejected the lower court’s invocation of TVA v. Hill, stating that “it is not our duty to prescribe optimal methods of legislation” but “[r]ather it is simply our duty to interpret statutes in accordance with the intent of the legislature.”[108]

Roe v. Casey is significant because the court recognized that each house enforces its rules. The court was thus right to look at the legislative record to see if, in fact, the houses waived the rule against legislating through appropriations. Should courts, however, necessarily assume that Congress has followed its rules if no waiver appears? Not necessarily.

Appropriations bills often contain authorizations through a number of different paths, in addition to formal waiver by the body.[109] Congress, for instance, can simply choose to not enforce its rules. A member must affirmatively raise a point of order in order to strike an authorization from the appropriations bill because legislative rules are not self-enforcing. If the members do not do so, perhaps because they support the bill’s substance or sense enough support to override a point of order, then the offending language remains.[110] Members may also fail to object to relatively minor provisions.[111]

In addition to the typical procedures available to waive legislative rules discussed above,[112] the House frequently creates a “special rule” for appropriations bills, which effectively allows such bills to avoid points of order under House Rule XXI.[113] Congress also often enacts continuing resolutions, rather than appropriations bills, which temporarily fund the government. Because these resolutions are not considered general appropriations bills, they are not subject to the rules forbidding authorization on appropriations.[114] In fact, this may partially account for the increasing use of continuing resolutions as the means to fund the government.[115]

Congress sometimes slips authorizations into omnibus appropriations. Traditionally, the appropriation bills were passed in thirteen separate measures. Omnibus bills bundle two or more of these bills. Like continuing resolutions, they fund a vast array of government programs and activities, but they are subject to House Rule XXI and Senate Rule XVI since they are considered general appropriations bills.[116] That being said, Congress often legislates in such bills, avoiding points of order since these are typically “must pass” measures politically speaking.[117]

These numerous paths by which each house may circumvent the prohibition on legislating in appropriations bills call into question whether courts should rely on these rules in the interpretive process. One option would be for a court, like the one in Roe v. Casey, to search the legislative record to see if Congress has waived the rules. But even this would not be sufficient. Since the rules are not self-enforcing, they are inherently politicized. Not following them may simply reflect support for the underlying legislation.

Returning to arguments in favor of using the rules in interpretation, Professor Nourse contends that courts who fail to see the influence of the rules upon the bill’s text and structure are likely to misunderstand the legislation.[118] She specifically references TVA v. Hill for support of her view.[119] As discussed above, the TVA v. Hill Court relied on legislative rules to argue that the appropriations could not have been for a project that violated the Act since Congress lacked the power to amend law via appropriations.[120] Despite this notable occurrence of judicial invocation of legislative rules, which would seem to support Nourse’s agenda, she takes a different approach than the Court.

Under Nourse’s view, the relevant rules prevent an authorizing committee from amending the bill with language contrary to the appropriations, which means that “appropriations trump authorizations.”[121] Nourse contends that Congress could not have amended the appropriations bill to make clear its intent to override the Act since doing so would have violated the rules. Thus, the Court’s application of the judicial canon against “repeal by implication” was inappropriate.[122] In her view, there was a repeal by implication precisely because Congress could not have explicitly repealed the relevant language in the Endangered Species Act even if it wanted to.[123] This understanding, however, overlooks the various methods in which Congress can circumvent its own rules.

The contradictory positions of the Court and Nourse also nicely illustrate another problem with relying on the rules in the interpretive endeavor. Even if we can prove Congress followed a rule precisely, it is difficult to ascribe a single meaning to that. The TVA v. Hill Court assumed Congress followed the rule against legislating in appropriations bills and came to the conclusion that Congress did not repeal the relevant part of the Endangered Species Act through the appropriation for the dam.[124] Nourse assumed the same yet concluded that Congress did effectuate the repeal. The quandary created by the rules gets the interpreter nowhere in this instance. It is equally plausible that Congress followed the rules by avoiding a repeal altogether and that it followed the rules by enacting a repeal by implication. It is also equally plausible that Congress meant to not follow the rules at all.

b. The Prohibition Against Inserting New Matter at Conference.—Turning to another legislative rule, before a bill becomes law, the House and Senate must pass the exact same measure with identical text.[125] Legislative differences between the two houses must thus be sorted out. One means to do so is the conference committee whereby several representatives from each house attempt to iron out the differences between the two positions in a conference bill.[126] Typically, this method is used for major bills.[127]

In theory, the rules of each house significantly restrict the scope of the conference. In practice, conferees have developed tactics to avoid such strictures. Senate Rule XXVIII(3) prevents conferees from “insert[ing] in their report matter not committed to them by either House” and from “strik[ing] from the bill matter agreed to by both Houses.”[128] In other words, the conference bill must only resolve differences between the House and Senate bills and cannot remove language that is the same in both bills. Doing so subjects the report to a point of order, which can be waived by three-fifths of the Senate.[129] House Rule XXII(9) has similar requirements for conference bills. Under this rule, conferees may only consider a “germane modification of the matter in disagreement,” which does not include “language presenting specific additional matter not committed to the conference committee by either House.”[130] As in the Senate, nongermane matters are enforced by points of order.[131]

This limitation on conferees is not as simple to interpret as it may seem. The conferees are limited to addressing the scope of differences between the House and Senate bills on a particular matter. The scope of differences includes the House position, the Senate position, and somewhere in between the two positions.[132] The range of permissible options may be easy to ascertain when the differences are quantitative.[133] For instance, if the House proposed a corporate tax rate of 20% and the Senate proposed 28%, then the permissible scope would be 20–28%. Anything higher or lower than that range would be nongermane.

If, on the other hand, the differences are more qualitative, then the permissible range may be far less easy to entertain, thus making enforcement of the rule difficult.[134] An example may help illustrate the conundrum. Under current federal income tax law, there is a top 21% rate on corporations and a top 20% rate on most dividends received from corporations. This structure is referred to as the “corporate double tax.” Suppose, for instance, the House passed a bill that eliminated the double taxation on corporate income (a reform referred to by tax experts as “corporate tax integration”[135]) by excluding dividend income in the hands of shareholders but also raised the corporate rate to 23%. The Senate bill, on the other hand, keeps the corporate double tax rate structure as is, including the corporate rate of 21%.

Would a conference agreement proposing an increase in the corporate rate from the current rate of 21% be considered nongermane? Perhaps, since the House bill’s plan to integrate the corporate tax could be seen as an overall reduction in the corporate double tax. On the other hand, just taking the corporate tax rate in isolation, the permissible range for conferees to consider could be 21–23%. The difference in kind between the two proposals complicates the germaneness inquiry. Accordingly, we can expect some slippage between the letter of the rules and how they are followed.

A primary way in which the restrictions on conferees are circumvented is when the second chamber passes an amendment in the nature of a substitute. Such an amendment replaces the entire text of the bill passed by the first chamber.[136] In such cases, the second chamber submits only one amendment to conference, even though the substitute bill could encompass many differences between the House and Senate versions. This makes it very difficult to identify the point of disagreement and the scope of the differences.[137] In such cases, the entire text of the bill is in play and policy differences may be acute.[138] This may mean that a conference substitute emerges that deviates from either approach. Although the rules intend to prevent this, assessing whether matter is “new” is often impractical.[139]

In general, points of order are rarely made against conference reports.[140] In the House, a two-thirds vote can suspend the rules, thus barring points of order, or a simple majority in the House can approve a special rule waiving points of order against a conference report.[141] If a member senses that waiver may be readily achieved, she may not bother making a point of order.

The threshold for waiver in the Senate is higher, requiring sixty votes, but the Senate has historically interpreted the conference rule generously. According to Riddick’s Senate Procedure, a conference report must simply avoid new “matter entirely irrelevant to the subject matter” in the prior bills.[142] The latitude is even greater with conference substitutes, which face “little limitation on their discretion, except as to germaneness,”[143] a requirement that has been interpreted in a “commonsense” manner.[144]

With all of this in mind, let us explore the risks of relying upon the conference rule in the interpretive process, which the Court has done on at least one occasion. In Union Electric Co. v. EPA,[145] the Court addressed the question of whether an operator of an electric company could raise the claim that it was infeasible to comply with a state implementation plan under the Clean Air Act.[146] The Court relied on the fact that both House and Senate bills contained language expressly providing that the states could submit plans that were stricter than the national standards.[147] The Conference Committee had deleted this language. But rather than taking that deletion to mean that the conferees intended to prohibit the states’ submission of stricter plans, the Court invoked the Senate and House rules to conclude that the deleted language was just superfluous. Since the conferees had no authority to change the agreed upon language, the remainder of the bill must have already reached the result of the deleted language.[148] Troublingly, the Court’s reasoning overlooked the possibility that lawmakers chose not to follow the rules and instead decided to change course as a policy matter.

Nourse invokes Public Citizen v. U.S. Department of Justice,[149] which addressed whether the American Bar Association (ABA) had to comply with the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA), which required that governmental entities “established or utilized” by the President meet certain procedural requirements.[150] The majority concluded that the ABA did not have to do so, arguing that if “utilize” took on its ordinary meaning of “use,” almost everyone who met with the President would be subject to the FACA requirements, leading to absurd results.[151] Instead, the majority, in a somewhat tortured fashion, interpreted “utilized” to mean “established.”[152]

Nourse carefully examines legislative history to show that, in light of congressional rules, “utilize” indeed is best read in the technical sense to mean “established.” In Public Citizen, the Senate bill covered entities “established or organized” by the President and the House bill used the term “established.”[153] According to Nourse, since “[c]onference committees cannot—repeat, cannot—change the text of a bill where both houses have agreed to the same language,” the term that was inserted at conference—“utilize”—should be read to conform to the language in the underlying bills.[154] In this case, utilize should be read to mean “established.” Reliance on the rules, according to Nourse, reaches the same result as the Public Citizen majority, but in a straightforward manner that avoids the controversial absurd-results canon.[155]

But is it so simple? Although both bills used the same “established” verbiage, the bills contained other differences in their definitions of advisory committees. The House definition of “advisory committees” applied to entities that were:

established or organized under a statute, an Executive order, or by other means, to advise and make recommendations to an officer or agency of the executive branch of the Federal Government or to the Congress, or both, but such term excludes standing or special committees of the Congress, any local civic group whose primary function is that of rendering a public service in relation to a Federal program, as well as any State or local committee, council, board, commission, or similar group established to advise or make recommendations to State or local officials or agencies.[156]

The Senate definition, in contrast, created two separate subcategories of “advisory committees,” first defining “agency advisory committees” as entities that were:

established or organized under any statute or by the President or any officer of the Government for the purpose of furnishing advice, recommendations, or information to any officer or agency, or to any such officer or agency and to the Congress, and which is not composed wholly of officers or employees of the Government.[157]

The Senate definition also applied to “presidential advisory committees” that were “established or organized under any statute or by the President for the purpose of furnishing advice, recommendations, or information to the President or the Vice President, or to the President or the Vice President and the Congress, and which is not composed wholly of officers or employees of the Government.”[158]

There are several things to note here. For one, although the Senate and House bills contained the same “established” language, the definitions more generally were divergent. Under the conference rules, the houses cannot consider new matters or matters on which they agree. Since the definitions themselves differed, they would have been up for grabs in the conference. This is because the relevant rules do not apply to words or phrases, but to “matters.”[159] Generally, this rule is applied on a provision-by-provision basis.[160]

Furthermore, as the Public Citizen Court noted, the Senate bill was an amendment by substitute that struck out the entire text of the House bill.[161] As a substitute version, it would have conferred on the conferees “wider latitude or wider scope for compromise in dealing with the matters in dispute,”[162] than in the case of amendments to various sections. The conferees would have had discretion to make modifications so long as these were germane to the underlying bills.[163] Although the conference report cannot introduce new matter, germaneness has been liberally interpreted in the case of substitute bills.[164]

But even if the definition of “advisory committees” was not in dispute, can we be confident that the legislative rules sufficiently cabined Congress such that the enacted “utilized” language had to have been construed as the agreed upon “established” language? Certainly not if the houses had waived the rules, as is often the case in the House at least.[165] And in the Senate, precedents have bestowed “considerable latitude” on conferees.[166] Intuiting where precisely such latitude ends would be difficult for a court to do. To complicate matters further, even if there is no evidence of waiver, senators and representatives may simply have chosen not to raise a scope point of order.

One could make an argument that courts must assume that members of Congress are “faithful agents” who follow the rules.[167] Even where the rules are evaded, for instance by inserting material at conference that was out of scope, a member voting on the material would assume the rules are followed and that the addition was immaterial. Thus, the general force of the rules still stands.[168]

It is unclear that members would necessarily assume the rules were being followed. Given the endogenous and politicized nature of legislative rules, an agent may fully grasp the reality that the rules are often broken, sometimes egregiously so, while still being “faithful” to the congressional enterprise. In other words, faithful adherence to the congressional enterprise does not require faithful adherence to the rules since the rules are meant to flexibly accommodate the political desires of the members.

Thus, a lawmaker who sees that “utilize” has been added to the conference report in Public Citizen may have simply assumed that conferees had taken latitude with the rules rather than that its meaning had not changed. She may have decided that a point of order was unwarranted given her agreement with the bill’s substance. Pretending that a member assumes rule compliance thereby erodes the self-executing nature of the rules, which presents separation of powers concerns as discussed below.[169]

B. The Budget Process

In addition to general legislative rules, the budget process prescribes intricate procedures for the houses through both statutory and internal rules. The basic scaffolding for the budget process is the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, which prescribes the development of Congress’s budget plan through the budget resolution.[170] The overarching goal of the process is to determine how much money Congress can spend each year, its spending priorities, and how those priorities can be funded.[171] The budget process has become of increasing importance due to (1) the reconciliation process, which circumvents the filibuster, and (2) PAYGO rules, which require deficit neutrality of new legislation. The following Section discusses possible methods by which courts could look to the budget process in statutory interpretation.

1. The Rules of Reconciliation

One challenge posed to interpreters is the increasingly nontraditional manner in which Congress legislates. Rather than following the classic path outlined in the Schoolhouse Rock cartoon, Congress deploys what Barbara Sinclair has labeled “unorthodox lawmaking.”[172] A notable example of this is the reconciliation process.[173] Reconciliation allows for legislation to pass without threat of filibuster and with limited debate and amendments. Majorities have used this powerful tool to pass major pieces of legislation, like the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The rushed process sometimes results in less-than-perfect legislation, to put it charitably.

As other scholars have noted, King v. Burwell[174] illustrates the Court’s possible turn toward recognition of unorthodox lawmaking in its interpretive presumptions.[175] The Court considered the question of whether a sloppily drafted tax provision providing for health insurance subsidies purchased through the “Exchange[s] established by the State” included insurance through state and federal exchanges or just the former.[176] The IRS had interpreted the Act as providing for tax subsidies not only in relation to state-run exchanges but federal ones as well. At stake was the health insurance of some 6.4 million Americans who purchased insurance through the federal exchanges and who received a subsidy.[177]

The Court ultimately construed the phrase at issue liberally to encompass federal exchanges. In so doing, the Court recognized the streamlined process by which the Act was enacted, reasoning that reconciliation took away “care and deliberation that one might expect of such significant legislation” resulting in “inartful drafting.”[178]

This case reflects an important willingness by the Court to adapt its interpretive rules based on congressional process. The Court could have easily embraced a purposive approach in interpreting the Affordable Care Act, reasoning that limiting insurance subsidies to state-run exchanges was perhaps within the letter of the statute but not its spirit.[179] It would have done so, however, by flouting the text of the statute. By instead grounding its reasoning in process, the Court privileges the text, albeit through unconventional interpretations of it.[180]

Courts may run into trouble, however, if they try to apply the rules of the reconciliation process on a more granular level. After senators began adding unrelated amendments to reconciliation bills in the 1980s, concern arose over how the process was being abused. West Virginia Senator Robert Byrd secured a safeguard, called the “Byrd Rule,” that prevents the Senate from considering a reconciliation bill with certain forbidden provisions.[181] Originally codified in 1985, the Byrd Rule has since been expanded and revised.[182] The Byrd Rule now allows a Senator to raise a point of order if reconciliation legislation includes a provision that is “extraneous.” A provision is “extraneous” if it:

(A) does not produce a change in outlays or revenues;

(B) produces an increase in outlays or decrease in revenues that does not follow the reconciliation instructions in the budget resolution;

(C) is not in the jurisdiction of the committee that reported the provision;

(D) produces changes in outlays or revenues that are merely incidental to the nonbudgetary components of the provision;

(E) increases the deficit in any fiscal year after the period specified in the budget resolution (i.e., the “budget window”); or

(F) recommends changes to Social Security.[183]

Like other legislative rules, the Byrd Rule is not self-executing.[184] A senator has to first challenge a provision on the grounds that it is extraneous. The Presiding Officer of the Senate then decides whether to sustain or overrule the point of order.[185] If sustained, unless sixty senators vote to waive the Byrd Rule or override the Presiding Officer, the offending provision must be excised from the bill.[186] Sixty senators can also overcome the Presiding Officer’s rejection of a point of order.[187]

In order to determine whether or not a provision is extraneous, the Presiding Officer consults with the Senate Budget Committee Chair or the Senate Parliamentarian.[188] The Senate Budget Committee Chair consults on challenges under subparagraphs (B) and (E) of the Byrd Rule and the Parliamentarian on the rest.[189] The Senate Budget Committee Chair uses Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and CBO estimates in making decisions under (B) and (E).[190] Thus, their estimates are crucial to passing these types of Byrd Rule challenges.

In Association of Accredited Cosmetology Schools v. Alexander,[191] a D.C. district court construed a statute that was passed through the reconciliation process so that it complied with subsection (A) of the Byrd Rule.[192] The D.C. district court was considering the meaning of a statute that affected the plaintiff school’s eligibility to participate in federal student aid programs. The statute excluded institutions with a “cohort default rate” equal or greater to a threshold percentage, which was 35% for 1991 and 1992 and 30% for any subsequent year.[193] The plaintiffs argued that the threshold percentages should be determined in the year the defaults occurred, while the government argued that they applied to the year in which the determinations of ineligibility were made.[194]

The court sided with the government, in part, because its interpretation was “most compatible with the underlying congressional purpose.”[195] The court rejected the plaintiff’s reading of the statute because it would have meant that the bill did not impact the budget in 1991. This would have subjected the bill to a point of order under the Byrd Rule.[196]

The flaw in the district court’s reasoning is that senators often do not raise points of order during reconciliation.[197] Moreover, the Parliamentarian’s rulings in this area are often nontransparent, inconsistent, and often reflect a judgment call that is not easily replicated by a court.[198] The ability of a judge to even discern Byrd Rule violations in the first place is questionable.

Consider a precedent from the 107th Congress. Senate Parliamentarian Robert Dove ruled that a measure setting aside $5 billion for natural disasters did not comply with the Byrd Rule since there would be no impact on revenues or outlays in the case of no natural disasters.[199] The ruling was heavily publicized because it prompted Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott to fire Dove.[200] Most of the time, however, the Parliamentarian’s rulings on the subject are not public. Instead, the Parliamentarian rules on Byrd Rule violations behind closed doors.[201] Only when senators or staffers disclose what transpired are we privy to how the Parliamentarian ruled and on what grounds.[202]

If a court were to try to apply the Byrd Rule on its own, it would thus be able to draw upon only a very narrow slice of the Parliamentarian’s rulings, which can prove challenging since the Byrd Rule is not always easy to apply. Take, for instance, the above example. Yes, it is true that, if there are no natural disasters, the $5 billion set-aside would not have impacted revenues or outlays. But from a risk-adjusted perspective, surely there would have been the expectation that the set-aside would have been drawn down somewhat. The ruling therefore reflected the idiosyncratic judgement of Robert Dove.

A similar issue arose in the context of the TCJA. Senator Bob Corker of Tennessee had predicated his support for the bill on the addition of a “trigger” mechanism that would have reversed some of the bill’s tax cuts if revenues fell below projections at a future date.[203] Reportedly, the Parliamentarian ruled that the provision violated the Byrd rule.[204] The rationale of the Parliamentarian is unknown, but the most likely explanation is that the trigger did not “produce a change in outlays or revenues.”[205] This is again a bit odd. The JCT listed the trigger as having a “negligible” effect on revenues, although it is unclear whether this means there were no costs or whether JCT was instead following CBO policy of not estimating budget costs or savings from measures targeting overall spending and revenues.[206]

Taking into account the expected value of the trigger, meaning both upside and downside risks, however, would have clearly cost the government revenues. A reasonable person could have decided the question very differently. Moreover, triggers have made their way into prior reconciliation bills. Expecting a judge to make such calls on how the Byrd Rule would have been interpreted by a Parliamentarian is problematic given the nontransparency of such prior rulings.

Muddying the picture further, the precedence of former rulings may not be given much weight. Even where the Parliamentarian’s rulings are available, they often conflict. Under subparagraph (D) of the Byrd Rule, the provisions cannot produce changes in outlays or revenues that are “merely incidental to the non-budgetary components of the provision.”[207] During consideration of the TCJA, the Parliamentarian aggressively applied this provision to remove several provisions from the bill, including:

A provision that would have required foreign airlines to pay corporate tax on some of their profits, producing $200 million in revenues;

A provision that would have allowed taxpayers to set up college savings plans for children who were not yet born but in utero, costing $100 million in revenues;

A provision that would have taken away the tax-exempt status of professional sports leagues, producing $100 million in revenues;

A provision that spared certain private foundations from an excise tax on for-profit companies they own, aimed at benefitting Newman’s Own and costing less than $50 million in revenues.[208]

The Parliamentarian even ruled against a TCJA provision that would have permitted charities to engage in political activities, costing $2.1 billion in revenues.[209] Contrast these provisions with earlier precedents that allowed a vaccine price provision even though CBO could not determine its score or an imported tobacco provision that netted only $6 million in revenues over five years.[210]

One could reconcile these decisions by making the determination that the TCJA provisions had a strong moral or policy component that overwhelmed any revenue coming in or out and the earlier provisions did not, but this is an inherently subjective determination that is impossible for a court to replicate. Further complicating matters, the Parliamentarian has recently started applying the Byrd Rule on a word-by-word and sentence-by-sentence basis, rather than the per-provision approach that was embraced by prior precedents and the statutory language of the Byrd Rule itself. This decision also produces unpredictable results.[211]

Even within the TCJA context, however, the Parliamentarian’s rulings are difficult to reconcile. She allowed, for instance, a provision expanding oil drilling in Alaska that would have raised only $910 million. According to scientists, its negative impact on wildlife most likely dwarfed the revenues gained from the provision, and somehow it still made it into the final bill.[212] Stranger still was the Parliamentarian’s decision to axe the short name of the bill, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, allegedly because it had “no budgetary impact.”[213] This departed radically from an earlier Parliamentarian’s view, who reasoned that the Byrd Rule “does not cover trifling matters.”[214]

In short, interpreting legislation to comport with the Byrd Rule has obvious shortcomings. Many times, the Parliamentarian’s rationales are not available, and predicting how they would have turned out is difficult given the conflicting precedents that do exist. Additionally, the particular provision at issue could have garnered sufficient support on its substance such that it avoided points of order altogether, notwithstanding a technical violation. On the other hand, the rules of reconciliation can tell the interpreter something about the legislative process that is helpful to the interpretation. The rules impart the information that Congress is operating with speed rather than deliberation. They need not be followed precisely in order to convey that to the interpreter.

2. CBO/JCT Scores

a. Black-Box Modeling.—Process-based theorists have recognized the rising importance of the budget process in lawmaking and have called upon courts to take this into account in the interpretive process. Professors Gluck and Bressman have advocated for the use of a CBO canon, which directs judges to interpret statutes so that they comport with the underlying assumptions of the official CBO estimates of the legislation in question.[215] Clint Wallace has extended this recommendation to the tax context, which utilizes estimates from the JCT.[216]

Predating this scholarly work, courts have sporadically relied upon CBO estimates in interpreting statutes. For instance, in 1982, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia held that a statute applied retroactively because the CBO estimates assumed as much.[217] In another case, the Seventh Circuit also decided a question of retroactivity utilizing CBO estimates.[218] Other courts have relied on other work product from CBO.[219]

Some courts have declined to rely upon CBO estimates. In a 2005 case, the Seventh Circuit interpreted whether the term “governmental entity” in the Electronic Communications Privacy Act required state, as well as federal, governments, to pay for information they sought from phone companies.[220] In so doing, they rejected a CBO opinion that the law would not impose new costs on states, reasoning that CBO’s view “on which Congress did not vote, and the President did not sign” could have been in error.[221] That case was later cited by a district court in Ohio, which rejected a CBO report in construing the scope of the ACA since the “CBO does not and cannot authoritatively interpret federal statutes.”[222]

The democratic concerns underlying the Seventh Circuit’s opinion should certainly give us pause, but if the scores are salient to Congress, which they undoubtedly are in many contexts, does this not at least somewhat alleviate the concern? Ultimately, if democratically elected members heavily rely upon CBO and JCT materials, then we should view those materials as incorporated into the democratic process.

The CBO and JCT estimates are attractive for reasons similar to the rules of reconciliation, in that they can impart general information to the interpreter even when the budget rules that inspire them are not being precisely followed. That is, the estimates matter even when Congress takes liberty with the rules.

Before we get to this, however, we must first answer a practical question. Are CBO estimates typically helpful to the interpreter? Many times, they are not. For instance, after a rushed legislative process, Congress enacted the TCJA, one of the largest overhauls to our tax system. The lack of deliberation contributed to the legislation being riddled with errors. One such example ended up being very costly to certain taxpayers. The omission of four words from the statute meant that retailers and restaurants could not take advantage of a provision that would have allowed them to immediately expense renovation costs, instead requiring them to depreciate the costs even more slowly than was granted under prior law.[223]

To illustrate, assume that a Dunkin’ franchise owner invests $1000 in a new donut-making machine. Under old law, a business owner would have gotten a deduction of $844. As intended, the new tax law would have allowed the owner to deduct the full $1000. As written, however, the new law allows a deduction of only $421. Since any technical corrections bill seems like an impossible feat in a sharply divided Congress, judges are left to resolve this conundrum—labeled as the “retail glitch”—in the interim.[224]

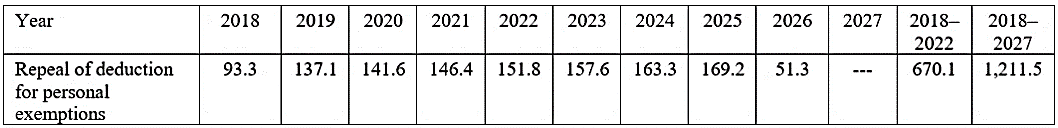

What would the JCT score of the TCJA tell us about whether Dunkin’ can deduct the costs of the donut-making machine? Not much, it turns out. This is because the relevant line item in the revenue estimate, like most such line items, does not unpack the assumptions that the JCT made in the scoring process. Instead, the JCT revenue estimates simply enumerate the cost of the relevant expensing provisions as applied to all taxpayers, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Expensing Provision Revenue Estimate in TCJA[225]

From this, we can discern only that the expensing provision in question will cost $86 billion over the ten-year budget window. There is no public breakdown of what the provision costs on a sectorial basis, so we have no insight as to whether JCT assumed the provision encompasses retailers and restaurants.

In many cases then, the CBO and JCT canons do little, if any, work. If, however, a judge wanted to try to understand JCT’s assumptions about the retail glitch, some contextual clues could assist in arriving there. For one, the conference report for the TCJA reflected that congressional intent was to give Dunkin’ and similar retailers and restaurants their deduction.[226] A judge could assume that JCT relied on the conference report in scoring the bill. Second, in scoring a later proposed (but never passed) technical corrections bill that would have fixed the retail glitch, among other errors, JCT concluded the bill had no revenue effect.[227]

This could be taken to mean that JCT originally assumed that the TCJA allowed expensing. All of this, of course, is circumstantial and does not illustrate with any certainty JCT’s assumptions. It also presents another interpretive puzzle. Since JCT appears to follow “congressional intent,” even when faced with contradictory text of the bill, isn’t this problematic for a textualist?

To be sure, there are instances where the revenue scores can assist the interpreter. Gluck and Bressman developed the CBO canon in the context of the aforementioned King v. Burwell challenge to the Affordable Care Act regarding when “Exchange[s] established by the State” included federal exchanges.[228] Like the JCT’s scoring of the TCJA, it is not possible to tell from the face of CBO’s estimate its assumptions regarding how the agency construed this language. The estimate merely showed a line item that the subsidies amounted to $350 billion in outlays over the ten-year budget window period.

Figure 2: Expensing Provision Revenue Estimate in ACA[229]

Later statements by CBO staff, however, aligned with the view that the agency assumed the subsidies were available on both federal and state exchanges. In a 2012 letter to House Oversight Chair Darrell Issa (R-CA), the CBO Director confirmed that the agency did not consider the possibility that the subsidies would only be available on state-created exchanges.[230] Some courts used this letter in their interpretation of the scope of the ACA.[231]

In the unique context of the ACA, the CBO made transparent its underlying assumptions. It did so in response to an official request by Representative Issa under Congress’s oversight authority. The majority of the time, however, the estimators do not make public their assumptions. In fact, outside of special requests from congressional members or committees, CBO and JCT rules prohibit staff from disclosing the inputs of their models.[232] To the extent the assumptions underlying the scores are opaque, members of Congress will be unable to ascertain what they are, let alone an interpreting court.

The secrecy shrouding the work of CBO and JCT is intentional. The entities do not provide enough details for Congress or other independent experts to replicate or second-guess their analyses, thereby insulating the estimators from politics.[233] The lack of transparency has even inspired legislation that would require the estimators to make their models and data available to legislators and the public.[234]

One could imagine that if courts began deploying the CBO and JCT canons with frequency, congressional members, under the guise of their oversight authority, might then pressure their staff to release their underlying assumptions in hopes of swaying the judicial outcome. This would undermine the ability of the estimators to fend off political pressure, with the benefit of more openness and transparency in the revenue estimating process. These considerations must be carefully balanced. In 2018, however, CBO announced an initiative to increase transparency.[235] These efforts may ultimately provide more useful material to the interpretive process.

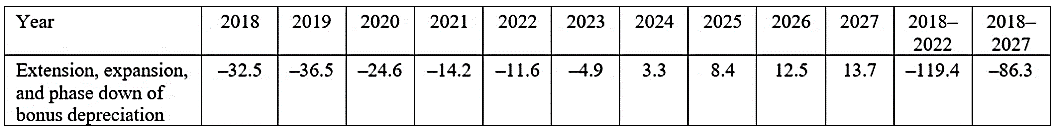

In some cases, the line items in the scores may be narrow enough to shed light on the interpretive question. Suppose, for instance, that a taxpayer argued that it was ambiguous whether TCJA repealed the deduction for personal exemptions. Consulting the official revenue estimates of the legislation, we can see that the JCT in fact scored such a repeal, and it was anticipated to add over a trillion dollars in revenue during the budget window period.[236]

Figure 3: Revenue Estimate for Repeal of Personal Exemptions in TCJA[237]

This would be fairly damning evidence that the JCT did not share the taxpayer’s interpretation of the provision in question.

Often, however, several elements of the law are often rolled into a single line item in the score. Also, even if the provision whose interpretation is in question warrants its own line item in the score, the precise interpretive question may not be binary such that the very existence of the score would tell the interpreter anything. For instance, if the taxpayer in our example is not arguing whether TCJA repealed the deduction but whether that repeal applied to her particular circumstances, the score will be of little use.

b. Contextualizing the CBO/JCT Canons.—So far, the above discussion illustrates that, although the CBO/JCT canons hold promise as reflecting modern congressional reality, they may only help the interpreter in certain circumstances. When information underlying the scores is available to the interpreter, however, we must first ask a preliminary question: In what contexts do the scores matter?

i. The Reconciliation Process.—Motivating Gluck and Bressman’s embrace of a CBO canon is empirical evidence they gathered indicating that congressional staff heavily relies upon the all-important score. In Gluck and Bressman’s survey to congressional staffers, 15% of respondents identified the Congressional Budget Office as a significant influence.[238] One staffer said, “[a]nything with a budget impact, we have to repeatedly go back to [CBO] to understand . . . their reading of the statute and then we have to go back and change it. This is extraordinarily widespread.”[239]

No doubt that the CBO and JCT scores have risen in importance in recent decades, but the degree depends heavily on the circumstances. In the context of the ACA, news outlets accurately reported that “the bill’s fate hinged on the results” of CBO’s analysis.[240] The reason, however, was not some immutable characteristic of the legislative process but one particular to reconciliation. At the time the health-care bill was being debated, the Democrats lost their sixtieth vote needed in the Senate and thus used the reconciliation process to enact parts of Obamacare.[241]

The CBO and JCT scores dramatically shape reconciliation legislation because sections (B) and (E) of the Byrd Rule require them as inputs, as discussed above.[242] The reconciliation instructions for the TCJA, for instance, restricted impact on deficits to $1.5 trillion over the budget window period.[243] Because its architects wished to bring the corporate tax rate down as low as possible while also giving individual tax cuts, even this high figure forced the creation of numerous provisions that helped offset the revenue losses. This was so that the legislation complied with subsection (B) of the Byrd Rule, which requires that the legislation stay within the parameters of the reconciliation instructions. More evidence of the Byrd Rule’s impact on the TCJA is that many of its key provisions expire at the end of 2025. This brought the legislation’s cost down to comport with (B) and also ensured that the legislation would not violate subsection (E) of the Byrd Rule, which prohibits bills from increasing the deficit beyond the budget window.

From this discussion, we can conclude that reconciliation is the appropriate context in which to deploy the CBO/JCT canons. As mentioned above, fiscal conservatives demanded that the TCJA’s impact be capped at $1.5 trillion, and the reconciliation instructions as adopted in the budget resolution set forth this figure. Given the ambitious list of tax changes Republicans wished to accomplish, it proved rather limiting. It is possible that in a different political environment, a much greater cap would have alleviated any fiscal constraints and diluted the impact of the JCT score. Still, in a fiscal environment of climbing deficits, the reconciliation instructions will most likely have high salience among congressional members.

There are tactics, however, that could arguably reduce the salience of the score.[244] In the months leading up to the TCJA’s enactment, Republicans toyed with the idea of lengthening the budget window. A longer budget window would heavily test the CBO and JCT because forecaster variables across a much longer time period introduce significant uncertainty. This is because the longer the estimating period, the more sensitive are the forecasts to subtle changes in the assumptions underlying the scores, such as discount rates, economic growth, and macroeconomic factors.[245] Costs inside the budget window would contain a large margin of error.[246] Measuring costs outside the budget window for purposes of ensuring compliance with subsection (E) of the Byrd Rule would become even more attenuated. Although the scorekeepers are technically tasked by subsection (E) to look at all periods beyond the budget window, this is an aspirational goal, and scorekeepers cannot reliably estimate many years into the future. If the budget window period were lengthened by decades, the subsection (E) analysis would become relatively meaningless.