Evaluating the Evaluator: Has the ABA Rated President Trump’s Judicial Nominees Fairly?

Since 1953, the American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary has evaluated presidential nominees for federal judgeships, rating them as Well Qualified, Qualified, or Not Qualified. The ABA insists that these ratings are “independent” and “nonpartisan,” but high-ranking Republicans, dating back to President George W. Bush and Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, have challenged this assertion. To date, research published in journals of law, political science, and economics has largely supported Republican suspicions, finding a pro-Democratic and anti-Republican bias in the ABA’s judicial ratings. Senators from both major parties have recently questioned the credibility of the ABA and have called for a federal investigation into the ABA’s judicial evaluation process. In the words of Democratic Senator Richard Blumenthal, “the ABA has to assess whether its ratings are going to continue to have the kind of credibility they had merited and deserved in the past.”

This Note takes up the question of the ABA judicial committee’s nonpartisanship. It evaluates the ABA ratings assigned to nominees for the U.S. courts of appeals, made during the administrations of George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump. This Note employs an ordered logistic regression model, it controls for relevant nonpolitical qualifications, and it finds no statistically significant difference in the way the ABA treated the appellate nominees of Presidents Bush, Obama, and Trump. Whatever was true in the past, today’s ABA ratings do not exhibit a clear partisan bias in either direction. The ABA’s judicial ratings favor appellate nominees who are legally experienced, regardless of the nominating president.

Introduction

In a national political environment that is increasingly polarized and where bipartisan agreement is increasingly rare,[1] Democrats and Republicans can agree on at least one thing: the influence and credibility of the American Bar Association (ABA) are shot. With declining membership and revenues, the ABA is quite literally half the organization it used to be.[2] It has lost much of its clout in the legal and political spheres. In the eyes of many lawyers and politicians, it seems outdated and “out of touch” with the modern world.[3]

Amid this general decline, the ABA’s Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary has not been spared. Since 1953, the ABA’s judicial committee has evaluated presidential nominees for federal judgeships, rating them as Well Qualified, Qualified, or Not Qualified.[4] These ratings have no formal authority, but they have traditionally been persuasive. Lately, there have been “complaints from both sides of the political divide that the ratings panel is more biased than ever . . . [and] irrelevant.”[5] “[T]he ratings have lost their ‘overall credibility from everybody,’”[6] and the editorial board of the nation’s largest newspaper has called for an end to the ABA’s advisory role in the federal judicial nomination and confirmation process.[7] Republican Senator Mike Lee has commented that the ABA has “lost its credibility as a neutral arbiter and should be treated no differently than any other special interest group,” and Republican Senator Ted Cruz accuses it of being “a partisan mouthpiece.”[8] Democratic Senator Sheldon Whitehouse has said, “I’m no fan of the ABA,”[9] and according to Democratic Senator Richard Blumenthal, “the ABA has to assess whether its ratings are going to continue to have the kind of credibility they had merited and deserved in the past.”[10] Members of both major political parties have called for a federal investigation into the ABA’s evaluation procedures.[11]

At the heart of this ongoing debate over the ABA’s credibility is the question whether the ABA’s judicial evaluations are fair. Are the evaluations based on an objective, nonpartisan assessment of a nominee’s legal qualifications, or are they instead based on the subjective political beliefs of the lawyers who sit on the ABA’s judicial committee? The ABA and its defenders insist that the committee’s ratings are fair. “We’re not here to become a political arm of anybody,” the committee’s chairwoman contended. “But this is a process that’s gone on for 60 years and we think we get it right most of the time.”[12] Offering little evidence, some academic defenders of the ABA have made similar assertions about the evaluation process.[13]

Whether the ABA’s judicial evaluations are fair is an empirical question, and it should be subjected to empirical analysis. Building on prior research, this Note evaluates the fairness of the ABA’s evaluations of nominees to the U.S. courts of appeals over the past two decades. Part I of this Note summarizes the ABA’s evaluation process, gives an abbreviated history of recent developments, and highlights previous studies, which have found that the ABA exhibits a systematic bias in favor of Democratic presidents’ nominees and against Republican presidents’ nominees. Part II comprises this Note’s own empirical analysis. It employs the same methodological approach as earlier research. The core finding of this Note is that ABA judicial evaluations in the twenty-first century have been fair. However well the ABA treated Democrats and however poorly it treated Republicans in the past, this century’s evaluations do not exhibit a clear partisan bias in either direction. Examining nominations made to the U.S. courts of appeals by Presidents George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump, this Note does not find a difference that rises to statistical significance. In other words, the appellate court nominees of Presidents Bush, Obama, and Trump have received substantially the same treatment. Contrary to the serious doubts of U.S. senators as well as the findings of previous scholars, this Note suggests that the ABA’s current process is free from partisanship and, from this standpoint, is fair. Today’s ABA is not biased toward Democrats or Republicans. It favors nominees who are legally experienced, regardless of the nominating president.

I. The Evaluation Process and Previous Findings of Partisan Bias

A. A Description of the ABA’s Evaluation Process

Since 1953, the ABA’s Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary has purported to offer “the Senate Judiciary Committee, the administration, and the public with its independent, nonpartisan peer evaluation of the professional qualifications of every judicial nominee to the Article III and Article IV federal courts.”[14] The committee is composed of fifteen members: the chair of the committee, one seat for each of the thirteen U.S. circuits, and an additional seat for the Ninth Circuit.[15] Committee members are lawyers whom the ABA president appoints, and they serve staggered three-year terms (one-third rotates off the committee each year).[16] During their tenure, members are disqualified from holding or seeking ABA office, abstain from partisan activities related to federal elections, and are bound by disclosure requirements.[17] The “cornerstone” of the committee’s evaluation process, says the ABA, is “confidentiality.”[18] In other words, the committee evaluates judicial nominees behind closed doors. It collects evidence, interviews individuals who know the nominee, and interviews the nominee.[19] Nominees do not know exactly what evidence the ABA uses or who testifies for or against them.[20]

The ABA sets forth the criteria that its judicial committee is supposed to use. Evaluations of nominees should be “directed solely to their professional qualifications: integrity, professional competence and judicial temperament.”[21] The ABA defines integrity as “the nominee’s character and general reputation in the legal community, as well as the nominee’s industry and diligence.”[22] It says professional competence “encompasses such qualities as intellectual capacity, judgment, writing and analytical abilities, knowledge of the law, and breadth of professional experience.”[23] And it describes judicial temperament as “the nominee’s compassion, decisiveness, open-mindedness, courtesy, patience, freedom from bias and commitment to equal justice under the law.”[24] The ABA recommends that “a nominee to the federal bench ordinarily should have at least twelve years’ experience in the practice of law.”[25] It further recommends that a nominee for a federal appellate court “should possess an especially high degree of legal scholarship, academic talent, analytical and writing abilities, and overall excellence.”[26] Needless to say, the ABA’s “professional qualifications” and their descriptions are vague. Outside the committee, nobody really knows how such factors as “general reputation” and “overall excellence” are measured and weighed. Furthermore, the ABA has decided to make its committee “insulated” against “all other activities of the ABA,” “ABA policies,” and other possible forms of external oversight conducive to fairness and accountability.[27]

When the review of a nominee has concluded, the ABA committee assigns one of three ratings: Well Qualified, Qualified, or Not Qualified.[28] “To merit a rating of ‘Well Qualified,’” says the ABA, “the nominee must be at the top of the legal profession in his or her legal community; have outstanding legal ability, breadth of experience, and the highest reputation for integrity; and demonstrate the capacity for sound judicial temperament.”[29] Next, a Qualified rating “means that the nominee satisfies the Committee’s very high standards with respect to integrity, professional competence and judicial temperament . . . [and] is qualified to perform all of the duties and responsibilities required of a federal judge.”[30] Lastly, a Not Qualified nominee is a nominee who “does not meet the Committee’s standards with respect to one or more of its evaluation criteria—integrity, professional competence or judicial temperament.”[31]

B. Early Research on ABA Bias and Recent Presidents

Early research into the ABA’s closed judicial evaluation process suggested unfair demographic bias. In a 1983 article, Elliot Slotnick found that high-income nominees usually received higher ratings than middle-income and low-income nominees, that men were almost three times as likely as women to receive high ratings, and that whites were three times more likely than minorities to receive high ratings.[32] Using more sophisticated statistical methods, Susan Haire substantiated Slotnick’s findings in 2001.[33] Controlling for fair and objective indicia of judicial qualification, such as a nominee’s education, academic experience, previous judicial experience, and experience practicing law, Haire found that minorities and women were still “much more likely to receive lower ratings” than white men.[34]

Around the same time, newly elected President George W. Bush and his Administration were critical of the ABA evaluation process, primarily due to their belief that the ABA was politically biased against Republicans.[35] “The question . . . is not whether the ABA’s voice should be heard in the judicial selection process,” proclaimed White House Counsel and future Attorney General Alberto Gonzales. “[It] is whether the ABA should play a unique, quasi-official role and thereby have its voice heard before and above all others.”[36] Over opposition from liberal advocacy groups and Democratic members of Congress, such as Senator Chuck Schumer, the Bush Administration broke with a half-century of tradition and announced that it would not consult the ABA judicial committee when selecting nominees.[37] Thereafter, the ABA would evaluate and rate candidates for federal judgeships on a post-nomination rather than pre-nomination basis.[38]

In 2009, Democratic President Barack Obama resumed pre-nomination consultation between the ABA and the White House, thus restoring the ABA to its previous, privileged position.[39] His successor, Republican President Donald Trump, followed President George W. Bush’s lead and excluded the ABA from the pre-nomination process.[40] In short, the difference between contemporary Democratic and Republican administrations is that Democrats consult with the ABA before they nominate candidates, whereas Republicans deny the ABA any quasi-official role, instead leaving the ABA judicial committee to conduct its evaluations after nominations are announced.[41] For Republican administrations, observes Professor Steven Calabresi, a different association of American lawyers—the Federalist Society—“has come to play . . . something of the role the American Bar Association has traditionally played.”[42]

C. Finding a Partisan Bias in ABA Ratings

Against the backdrop of studies finding racial and sexual bias in the ABA’s judicial ratings and contemporaneous with the Bush Administration’s humbling of the ABA shortly after the 2000 election, scholars began to scrutinize the ABA ratings for potential partisan bias. The first landmark study in this regard was James Lindgren’s 2001 article published in the Journal of Law & Politics.[43] Comparing ABA ratings given to the appellate court nominees of Republican President George H. W. Bush (1989–1993) and Democratic President Bill Clinton (1993–2001), Lindgren found a strong pro-Clinton, pro-Democratic bias. Controlling for prior judicial experience, an elite law school education, membership on the law review during law school, federal clerkship experience, private practice experience, and government practice experience,[44] Lindgren found that “the odds of getting a Well Qualified rating [we]re 9.1 times higher for Clinton appointees than for Bush appointees. For every five lower rated candidates, Bush would get only one highly rated candidate; Clinton would get nine.”[45] Lindgren continued, “Just being nominated by Clinton instead of Bush [wa]s better than any other credential or than the other credentials put together.”[46] In other words, Lindgren’s study showed that, in practice, being a Democrat was the best credential one could have in the eyes of the ABA judicial committee. Democratic affiliation, according to Lindgren, was a stronger predictor for a Well Qualified rating than judicial experience, legal education, law review, clerkship, private practice experience, or government service. It was the ABA’s overriding criterion.[47]

The Lindgren study predictably sparked criticism.[48] Nonetheless, later studies corroborated his basic claim—that the ABA judicial committee, in assigning ratings, exhibited bias toward Democrats and against Republicans. Instead of relying on objective, non-political qualifications, the primary or major criterion for assessing a nominee’s fitness, at least for appellate judgeships, was the nominee’s political identity as a Democrat or Republican. For the ABA judicial committee, partisan identification outweighed or else was used as a proxy for a nominee’s integrity, professional competence, and judicial temperament.

In 2012, political scientists Susan Navarro Smelcer, Amy Steigerwalt, and Richard Vining reexamined the view that the ABA rates nominees with a partisan bias.[49] They collected data on nominations to the U.S. courts of appeals from 1977 to 2008.[50] Their finding supported the basic hypothesis and finding of the 2001 Lindgren study. Controlling for race, sex, age, federal judicial experience, state judicial experience, prosecutorial experience, private practice experience, professorial experience, federal appellate clerkship experience, and political experience, the Smelcer study found

that “nomination by a Democrat increases the probability of receiving a

Well Qualified rating by approximately 15 percent.”[51] To be sure, this effect

was smaller than the effect found by Lindgren, likely due to a larger sample

size, more control variables, and methodological differences. Concluding their article, Smelcer, Steigerwalt, and Vining suggested that the

ABA’s partisan bias might be explained by “ideological bias against conservatives,” by “different qualities” or other unique characteristics not captured in the statistical model, or by “an inherent liberal bias” in the ABA’s evaluation criteria.[52] Perhaps, on this last point, the ABA’s consideration of values such as “compassion” and “open-mindedness,” to the exclusion of more conservative values such as order and respect for tradition, biased ratings toward Democrats.[53] In a follow-up study that the same authors published two years later, they found that the ABA’s partisan bias favoring Democrats and disfavoring Republicans did not extend to federal district court nominees, who “are assessed solely on the basis of their professional qualifications, which is likely due to their distinct tasks and positions in the federal judicial hierarchy.”[54]

Likewise, economist John Lott published an article in 2013 that “reveal[ed] the ABA as systematically giving much lower ratings to Republican than Democratic circuit court nominees, even when qualifications were the same.”[55] The data extended from President Jimmy Carter through the first term of President George W. Bush, and Lott included a long list of control variables in his model.[56] As with Smelcer and colleagues, Lott did not find partisan bias in the ABA ratings of federal district court nominees.[57] In sum, researchers in law, political science, and economics have discovered partisan bias in the ABA’s evaluations of nominees for the U.S. courts of appeals.

II. Empirical Analysis: Presidents Bush, Obama, and Trump

A. Data and Research Design

This Note builds on the aforementioned studies regarding the ABA’s partisan bias. The units of analysis are individuals nominated to the U.S. courts of appeals. This Note has collected data on nominations made by Presidents George W. Bush (a Republican), Barack Obama (a Democrat), and Donald Trump (a Republican) from January 2001 through mid-October 2020.[58] The dependent variable is the ABA judicial rating assigned to a nominee: Well Qualified, Qualified, or Not Qualified.[59] Because this dependent variable is ordinal, some form of ordinal regression is appropriate. Following previous studies, this Note uses ordered logistic regression.[60]

The independent variables of greatest interest are indicator (or dummy) variables for the recent nominating presidents. Out of 204 appellate nominees in this Note’s sample, 41% were nominated by President Bush, 33% were nominated by President Obama, and 26% have been nominated by President Trump. This Note’s model holds out Bush nominees as the reference category against which Obama nominees and Trump nominees are compared. Selection of Bush nominees as the baseline is reasonable given that President Bush is the earliest president in the sample and the president who chose a plurality of the sample’s nominees.

Next, this Note includes indicator variables for male nominees, nominees with previous experience as a federal district court judge, and nominees with previous experience as a clerk for a federal appellate judge. In the model that the Smelcer study estimated, these variables were at least significant at the p < .10 level.[61] Those results suggest that the ABA has favored male nominees over female nominees, nominees who have been federal district court judges, and nominees who have worked as clerks for federal appellate judges.

This Note adds two more variables. The first is the prestige of the law school from which an appellate nominee graduated. For this purpose, this Note has classified law schools on a continuous scale running from 1 to 100. To classify a law school, this Note used the median Law School Admission Test (LSAT) score from 2018 as a proxy for law school prestige.[62] Then, median LSAT scores were converted into percentile scores using an official conversion chart from the Law School Admission Council (LSAC), which administers the LSAT.[63] For the appellate nominees examined in this Note, the most prestigious law schools are Harvard and Yale, whose median students rank at the 99.1st percentile of exam takers. The least prestigious law school is North Dakota, where the median student ranks at the 36.9th percentile. My expectation is that the ABA favors nominees who graduated from prestigious law schools on the presumption—right or wrong—that such nominees are more intelligent and capable.

Next, this Note includes a nominee’s years of experience as a lawyer. To calculate this variable, this Note subtracted the year in which a nominee graduated law school from the year in which the nominee was nominated to be a federal appellate judge. On this measure, the least experienced nominees were nominated a mere 11 years after their graduations from law school, the most experienced nominee was 45 years out of law school, and the average nominee graduated law school 24 years before nomination. My expectation is that lawyerly experience positively affects the ABA’s evaluation of a nominee. Although lawyerly experience is not directly related to the ABA’s stated criteria of integrity, professional competence, and judicial temperament, more experienced lawyers are likely perceived to have higher degrees of competence, as well as integrity and temperament, than more junior members of the profession.

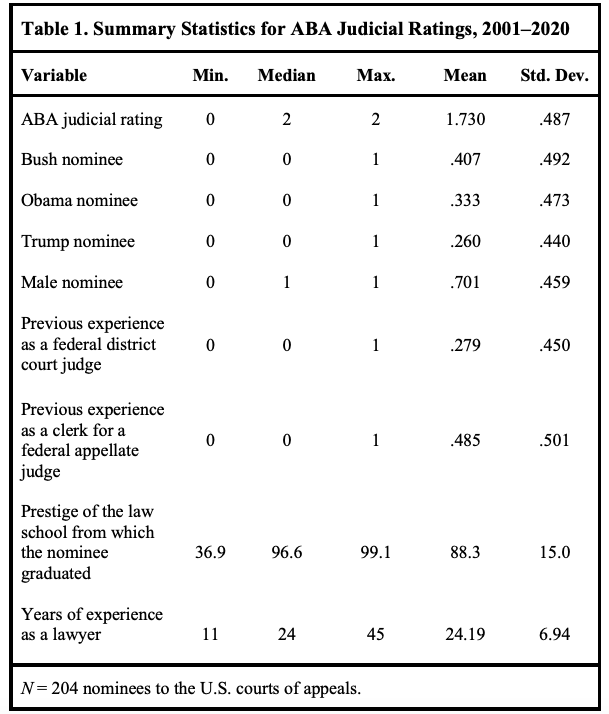

Table 1 gives summary statistics for this Note’s variables. The null hypothesis is that ABA ratings have no partisan bias. The alternative hypothesis is that a partisan bias exists, and previous research strongly suggests it would be a partisan bias favoring Democratic nominees and disfavoring Republican nominees. If so, the coefficient estimate for Obama nominees should be positive and statistically significant. For Trump nominees, a coefficient estimate near zero would indicate performance similar to that of Bush nominees. A positive or negative coefficient estimate would indicate that Trump nominees have outperformed (positive) or underperformed (negative) Bush nominees on their ABA ratings.

B. Results

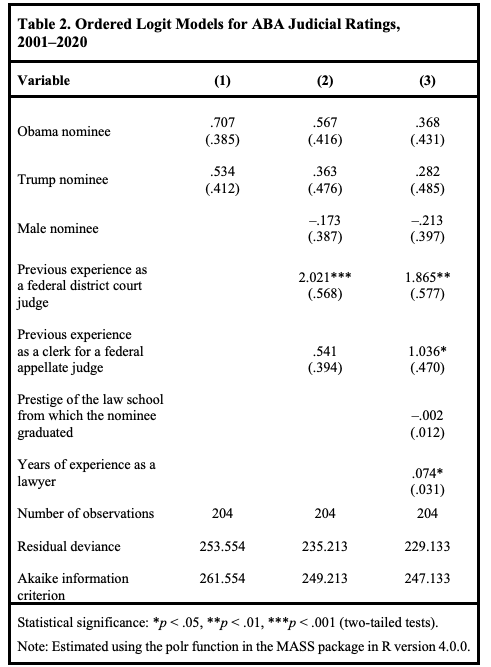

Table 2 displays the results of this Note’s analysis. In the first column, this Note estimates coefficients (outside parentheses) and standard errors (inside parentheses) for the independent variables: Obama and Trump nominees. In the second column, this Note adds several control variables, significant in the Smelcer study.[64] The third column shows this Note’s full model with all variables, including law school prestige and lawyerly experience. Using the Brant package in R, three Brant tests were conducted (one for each column of results in Table 2), and these tests show that the proportional odds assumption is met.[65]

As Table 2 shows, neither the indicator variable for Obama nominees nor the indicator variable for Trump nominees is statistically significant. (Keeping with standard practice in the social sciences, this Note sets the threshold for statistical significance at p < .05.) This means the null hypothesis that the ABA evaluates nominees without partisan bias cannot be rejected. In other words, the ABA gave similar ratings to appellate court nominees in 2001–2020, regardless of the nominating president—Bush, Obama, or Trump. As control variables are added in the second and third columns of Table 2, the coefficient estimates for Obama and Trump nominees move closer to zero, and the standard errors increase. These changes in the coefficients and standard errors are consistent with and further bolster the conclusion, in favor of the null hypothesis, that appellate nominees from 2001 to 2020 were treated roughly equally. The lack of statistical significance in my results is analytically significant because it runs against the earlier results of the Lindgren study, the Smelcer study, and the Lott study, which found that the ABA exhibited a partisan bias in favor of Democrats and against Republicans. This Note’s null finding lends support to the ABA’s claim that its judicial ratings are nonpartisan and fair.

In Table 2, three variables are statistically significant: previous experience as a federal district court judge, previous experience as a clerk for a federal appellate judge, and years of experience as a lawyer. Their estimated coefficients all point in the expected direction. Indeed, the ABA gives higher ratings to nominees when they have prior experience as a federal district court judge or a federal appellate clerk.[66] Moreover, a lawyer who has more years of experience at the time of nomination is more likely to receive a higher rating from the ABA. In the sample, a nominee’s sex and law school prestige do not significantly affect the ABA rating.

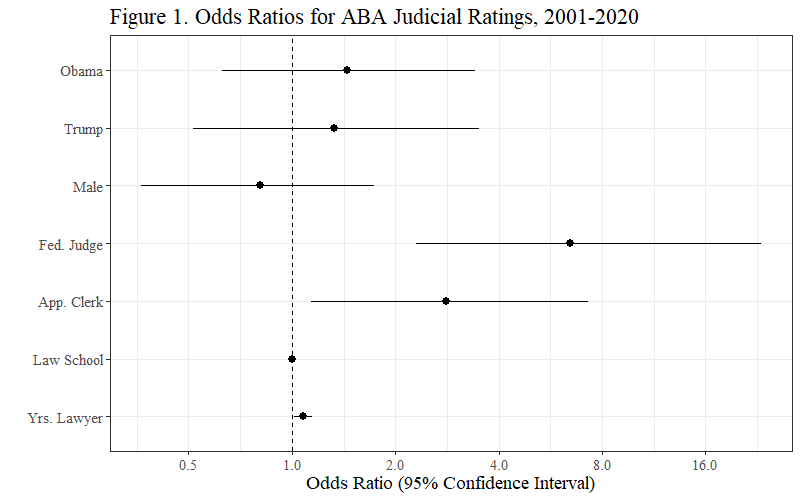

The coefficients for an ordered logistic regression are log odds ratios. These ratios are difficult to interpret in substantive terms. Therefore, this Note has exponentiated (the exp function) the results from the full model in column 3 of Table 2. Figure 1 displays the (unlogged or anti-logarithmic) odds ratios as a forest plot. The bullets are point estimates for each variable’s effect on the ABA rating, and the whiskers are 95% confidence intervals. Holding other variables constant, the odds ratio for a nominee with experience as a federal district court judge is 6.453, and the odds ratio for a former federal appellate clerk is 2.817. In other words, the relative odds that a federal district court judge will receive a higher rating from the ABA than a non-judge and the relative odds that a former federal appellate clerk will receive a higher rating from the ABA than a non-clerk are about 6-to-1 and 3-to-1 respectively. These odds ratios are both statistically significant and substantial in their magnitudes. Prior federal judicial experience and clerkship experience are important.

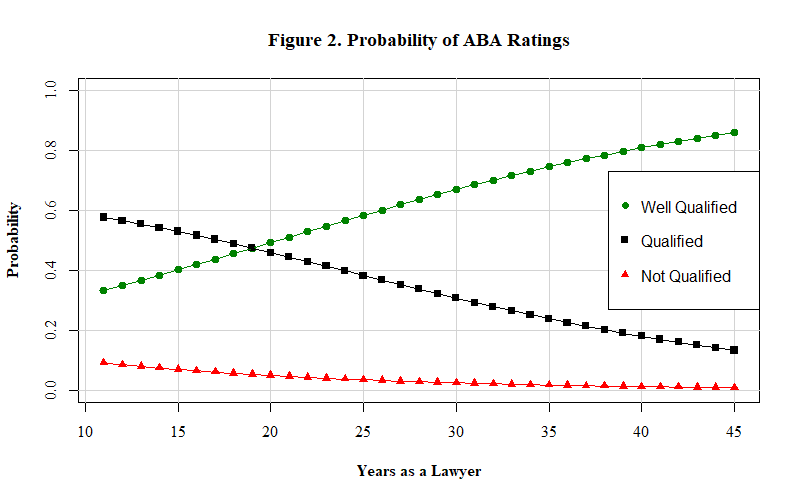

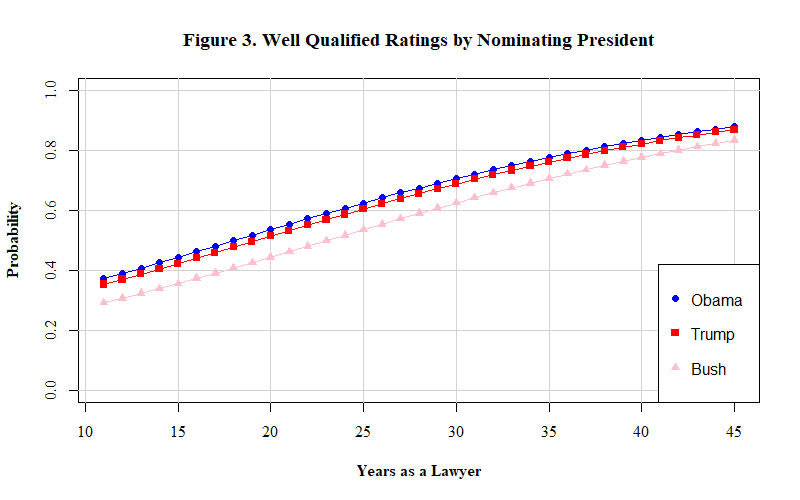

Years of experience as a lawyer is also statistically significant. The odds ratio is 1.076, and the 95% confidence interval stretches from 1.015 to 1.146. In other words, the relative odds that a lawyer with one extra year of experience will receive a higher ABA rating than a similarly situated lawyer are about 1.1-to-1. The magnitude of this result is substantial, although it is not apparent to the naked eye. Thus, in Figure 2 and Figure 3, this Note presents probability curves. The first set of curves (Figure 2) shows the probability that the ABA will rate a nominee as Well Qualified, Qualified, or Not Qualified based on the number of years since law school graduation, ranging from 11 years to 45 years (the same range as the sample). The second set of curves (Figure 3) shows the probability that the ABA will rate a nominee as Well Qualified given the identity of the nominating president. Figure 2 holds the variables for Obama, Trump, and law school prestige constant at their means,[67] and it holds the variables for male, federal district court judge, and appellate clerk at their medians or modes (identical values for a binary variable). Figure 3 holds law school prestige at its mean, and it holds the variables for male, federal district court judge, and appellate clerk at their medians or modes (as with Figure 2).

The effect of years of experience as a lawyer on an appellate nominee’s ABA rating was not apparent in the ordered logistic estimates (Table 2) nor in the forest plot (Figure 1). However, its effect is apparent in Figure 2 and Figure 3. For example, Figure 2 shows that an appellate nominee with fifteen years of experience as a lawyer has a 40% chance of receiving an ABA rating of Well Qualified, a nominee with twenty years of experience has a 49% chance, and a nominee with twenty-five years of experience has a 58% chance, holding other factors constant. The probability of being rated as Well Qualified also increases with lawyerly experience in Figure 3. Obama nominees cross the 50% threshold in their nineteenth year, Trump nominees cross the 50% threshold in their twentieth year, and Bush nominees cross the 50% threshold in their twenty-fourth year following law school graduation. These differences are not significant at the p < .05 level, or the 95% confidence level. In short, the ABA treated Bush, Obama, and Trump nominees approximately the same (without partisan bias).[68]

Conclusion

The subtitle of this Note asks: Has the ABA Rated President Trump’s Judicial Nominees Fairly? The answer: yes, on average. This Note’s analysis finds no statistically significant difference in the way the ABA judicial committee has treated the nominees of Presidents Bush, Obama, and Trump for the U.S. courts of appeals. In other words, this Note does not corroborate the findings of earlier studies. However, this does not mean the earlier studies were wrong. Indeed, Lindgren examined ABA judicial ratings from 1989 to 2001, Lott examined ratings from 1977 to 2004, and Smelcer and colleagues examined ratings from 1977 to 2008.[69] This Note, on the other hand, evaluates the ABA’s evaluations in the twenty-first century—from 2001 to 2020. Most of its data (twelve years out of twenty years) come from nominations that were not examined in any of the earlier studies. Assuming the earlier studies are sound, the import of this Note is that ABA ratings have become less partisan, or more impartial, in the past two decades. In the 1980s, the 1990s, and perhaps into the 2000s, the ABA appears to have exhibited a bias favoring Democratic nominees and disfavoring Republican nominees. Over the Bush, Obama, and Trump administrations, though, the ABA’s partisan bias has evaporated, and it is now nonexistent or at least undetectable at statistically significant levels. It no longer seems to matter to the ABA judicial committee whether appellate nominees are Democrats or Republicans, provided they meet objective qualifications.

What might have prompted this shift in the ABA’s judicial ratings from partisan, pro-Democratic bias to nonpartisan neutrality? This Note has not collected evidence that could answer this question. Indeed, if such evidence exists at all, it would likely be found only within ABA documents that are not publicly available due to the judicial committee’s closed-door evaluation process. This Note’s suspicion is that the ABA committee made a course correction. It responded to criticisms from Republicans and others, starting with President Bush and his Administration in 2001—when they humbled the ABA by removing it from its quasi-official role. If the ABA wants to cultivate respect in the legal and political spheres, if it wants decision-makers and the general public to believe it is a nonpartisan professional association, and if it wants to regain its overall credibility, then it actually has to behave in a nonpartisan manner and not as a booster for Democratic nominees. When Republicans and researchers threw a light upon the ABA and its bias against the appellate nominees of Republican presidents, the ABA might have been motivated to change its ways. Whether this influence on members of the ABA committee was conscious or unconscious, it seems to have made an impact.

This Note’s findings suggest that current ABA ratings, as contrasted with past ratings, reflect a good-faith effort at “independent, nonpartisan peer evaluation.”[70] To paraphrase one insider familiar with the evaluation process, the ABA judicial committee is not nearly as biased as it used to be.[71] Many recent criticisms against the ABA committee are exaggerated and unwarranted,[72] and its most recent ratings are certainly not “more biased than ever.”[73] Statistical analysis does not bear out these accusations. The ABA might have shown bias toward Democrats and against Republicans in the past, but this bias is no longer apparent in its present-day judicial evaluations. For the past twenty years or so, the key explanatory factors for ABA ratings have been previous judicial experience, clerkship experience, and years as a lawyer, not the identity of the nominating president.[74]

- .See Sean M. Theriault, Party Polarization in Congress 3 (2008) (describing increasing polarization among Americans); see also Congress at a Glance: Major Party Ideology, Voteview.com, https://voteview.com/parties/all [https://perma.cc/TLC5-4GY7] (depicting the growing ideological divide between congressional Democrats and Republicans). See generally Keith T. Poole & Howard Rosenthal, A Spatial Model for Legislative Roll Call Analysis, 29

Am. J. Pol. Sci. 357 (1985) (introducing NOMINATE scores); Keith T. Poole & Howard Rosenthal, Patterns of Congressional Voting, 35 Am. J. Pol. Sci. 228 (1991) (explaining the underlying mathematics). ↑ - .See Melissa Heelan Stanzione, New ABA Membership Strategy Aims to Reverse

Slide, Bloomberg Law (May 1, 2019, 10:10 AM), https://news.bloomberglaw.com/

business-and-practice/abas-new-membership-model-logo-go-into-effect [https://perma.cc/TCZ2-G7EA] (observing that in the past four decades, ABA membership has fallen from 50% of U.S. lawyers to 20% of U.S. lawyers and that less than half of ABA members actually pay dues). ↑ - .E.g., Mark A. Cohen, Is the American Bar Association Passé?, Forbes (Aug. 1, 2018, 6:01 AM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/markcohen1/2018/08/01/is-the-american-bar-association-passe/ [https://perma.cc/P7SZ-ZKHW]. ↑

- .Am. Bar Ass’n, Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary: What It

Is and How It Works 1, 6 (2017), https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/

administrative/government_affairs_office/backgrounder-current-as-of-4-8-2020.pdf [https://perma

.cc/T26B-YD8Q]. ↑ - .Madison Alder & Melissa Heelan Stanzione, Judicial Ratings Draw Ire of Left, Right After Tearful Hearing, Bloomberg Law (Nov. 6, 2019, 3:51 AM), https://news.bloomberglaw.com/

us-law-week/judicial-ratings-draw-ire-of-left-right-after-tearful-hearing [https://perma.cc/FC5V-NAWS]. ↑ - .Id. ↑

- .The Editorial Board, Ruling Out the ABA on Judges, Wall St. Journal (Nov. 14, 2017) [hereinafter WSJ Editorial Board], https://www.wsj.com/articles/ruling-out-the-aba-on-judges-1510703170 [https://perma.cc/2DAR-AYET]; see Top 10 U.S. Newspapers by Circulation, Agility PR Solutions (Jan. 2020), https://www.agilitypr.com/resources/top-media-outlets/top-10-daily-american-newspapers/ [https://perma.cc/U7UA-3RB8] (“The Wall Street Journal is America’s largest newspaper by paid circulation . . . .”). ↑

- .Susan Crabtree, GOP Critics: ABA to Face Senate Action After Suspect VanDyke Rating, RealClearPolitics (Nov. 6, 2019), https://www.realclearpolitics.com/articles/2019/11/06/gop_critics_aba_faces_senate_action_after_suspect_vandyke_rating__141670.html [https://perma.cc/LED5-S9Q6] (quoting Senators Mike Lee and Ted Cruz). ↑

- .Id. (quoting Senator Sheldon Whitehouse). ↑

- .Alder & Stanzione, supra note 5. ↑

- .Crabtree, supra note 8. ↑

- .Tim Ryan, Senate Scours American Bar Association for Liberal Bias, Courthouse News Serv. (Nov. 15, 2017), https://www.courthousenews.com/senate-scours-american-bar-association-liberal-bias/ [https://perma.cc/6ZSC-HLMT] (quoting the committee chairwoman, Pamela Bresnahan). ↑

- .See, e.g., Carl Tobias, Filling the Texas Federal Court Vacancies, 95 Texas L. Rev. See Also 170, 194 n.157 (2017) (“[T]he ABA evaluations and ratings are very professional, offer valuable insights and can save the candidates and the administration from embarrassment, should problematic revelations arise later in the process.”). ↑

- .Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary, ABA, https://www.americanbar

.org/groups/committees/federal_judiciary/ [https://perma.cc/C2B7-7V7G]; Am. Bar Ass’n, supra note 4, at 1. ↑ - .Am. Bar Ass’n, supra note 4, at 1. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 2. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .See id. at 4–6 (providing an overview of the process). ↑

- .See id. at 3 (“The Committee maintains the strict confidentiality of the identity of all judges, lawyers and all other individuals who provide information regarding the professional qualifications of a nominee unless the interviewee has agreed to waive confidentiality.”). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. at 2. ↑

- .Id. at 6. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. Yes, according to the ABA, a Qualified nominee is a nominee who “is qualified.” ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Elliot E. Slotnick, The ABA Standing Committee on Federal Judiciary: A Contemporary Assessment—Part 2, 66 Judicature 385, 386–87 (1983). At the time, the ABA assigned one of four ratings to a nominee: Exceptionally Well Qualified, Well Qualified, Qualified, or Not Qualified. Id. ↑

- .Susan Brodie Haire, Rating the Ratings of the American Bar Association Standing Committee on Federal Judiciary, 22 Just. Sys. J. 1, 7–8 (2001). She used logistic regression rather than descriptive statistics. Id. at 7. ↑

- .Id. at 7–8. ↑

- .Amy Goldstein, Bush Curtails ABA Role in Selecting U.S. Judges, Wash. Post

(Mar. 23, 2001), https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2001/03/23/bush-curtails-

aba-role-in-selecting-us-judges/ebfe106c-344d-40a0-8dff-ccf0a2e411fe/ [https://perma.cc/3TBV-FS2Z]. ↑ - .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Am. Bar Ass’n, supra note 4, at 1. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Lydia Wheeler, Meet the Powerful Group Behind Trump’s Judicial Nominations, The Hill (Nov. 16, 2017, 6:00 AM) (quoting Steven Calabresi), https://thehill.com/regulation/court-battles/360598-meet-the-powerful-group-behind-trumps-judicial-nominations [https://perma.cc/DD8Z-ELQL]. ↑

- .James Lindgren, Examining the American Bar Association’s Ratings of Nominees to the U.S. Courts of Appeals for Political Bias, 1989-2000, 17 J.L. & Pol. 1 (2001). ↑

- .Id. at 7. ↑

- .Id. at 9. ↑

- .Id. at 10. ↑

- .See also John R. Lott, Jr., The American Bar Association, Judicial Ratings, and Political Bias, 17 J.L. & Pol. 41, 47 (2001) (suggesting that the ABA judicial committee especially targeted Republican nominees who were African Americans, thus layering racial discrimination and political bias on top of one another). ↑

- .E.g., Michael J. Saks & Neil Vidmar, A Flawed Search for Bias in the American Bar Association’s Ratings of Prospective Judicial Nominees: A Critique of the Lindgren Study, 17 J.L. & Pol. 219 (2001). Saks and Vidmar raised several concerns in their critique, including that Lindgren’s sample suffered from selection bias because a Democratic president was more likely than a Republican president to give prospective consideration to the ABA’s views and then to choose nominees accordingly; that Lindgren did not adequately conceptualize and measure integrity, professional competence, and judicial temperament, which are the criteria the ABA says it uses; and that proxy and dummy variables could not do justice to the complexity of rating nominees and their professional backgrounds. Id. passim. “The measures proposed [by Lindgren] to be relied on are plausible for the general population of lawyers,” said Saks and Vidmar. “But those measures are incapable of making fine distinctions among the small elite corps of lawyers who have reached the threshold of a presidential nomination to the Courts of Appeals.” Id. at 245. Saks and Vidmar also attacked the Lindgren study for using data compiled by the Federalist Society. Id. at 250. Lindgren wrote a thirty-nine-page response to Saks and Vidmar’s critique. See generally James Lindgren, Saks and Vidmar: A Litigation Approach to Social Science, 17 J.L. & Pol. 255 (2001). ↑

- .Susan Navarro Smelcer, Amy Steigerwalt & Richard L. Vining, Jr., Bias and the Bar: Evaluating the ABA Ratings of Federal Judicial Nominees, 65 Pol. Res. Q. 827, 827 (2012). ↑

- .Id. at 830. ↑

- .Id. at 832. ↑

- .Id. at 837. ↑

- .Id.; see supra note 24 and accompanying text (defining judicial temperament). ↑

- .Susan Navarro Smelcer, Amy Steigerwalt & Richard L. Vining, Jr., Where One Sits Affects Where Others Stand: Bias, the Bar, and Nominees to Federal District Courts, 98 Judicature 35, 36 (2014). In 2012, Dustin Koenig published a paper critical of a preliminary version of the first Smelcer study. Dustin Koenig, Bias in the Bar?: ABA Ratings and Federal Judicial Nominees from 1976–2000, 95 Judicature 188, 190 (2012). Koenig’s paper does not merit serious attention because it is methodologically deficient. Koenig’s “political” variables appointing president, political ideology, and party affiliation are highly collinear, and this collinearity adversely affects his results. On the “monster” of collinearity in logistic regression analysis, see generally Habshah Midi, S. K. Sarkar & Sohel Rana, Collinearity Diagnostics of Binary Logistic Regression Model, 13 J. Interdisc. Mathematics 253 (2010). (Ordered logistic regression is an extension of binary logistic regression, and the same problems of collinearity exist.) ↑

- .John R. Lott , Jr., ABA Ratings: What Do They Really Measure?, 156 Pub. Choice 139, 160 (2013). ↑

- .Id. at 151. ↑

- .Id. at 160. ↑

- .This Note takes most of its data from the Federal Judicial Center’s Biographical Directory of Article III Federal Judges, 1789-present, Fed. Judicial Ctr., https://www.fjc.gov/history/judges [https://perma.cc/VG6M-VF4V]. Other websites from which this Note draws data include those of the American Bar Association, the Law School Admission Council, and law firms (for information on nominees whom the Senate did not confirm). ↑

- .Ratings, Am. Bar Ass’n, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/committees/federal_judiciary/ratings/ [https://perma.cc/GC9C-9Y3P]. Some scholars have used larger ordinal scales, where they distinguish between unanimous and non-unanimous ABA evaluations. See, e.g., Smelcer et al., supra note 49, at 830 (using a seven-point ordinal scale). In using a three-point ordinal scale, this Note follows the ABA’s description of its own evaluation process and thus assumes that the final rating—Well Qualified, Qualified, or Not Qualified—is all that really matters. ↑

- .See supra notes 43–57 and accompanying text (citing previous studies on ABA ratings). As statisticians have observed, logistic (logit) and probit models produce similar results, and noticeable differences appear only in larger datasets. Guo Chen & Hiroki Tsurumi, Probit and Logit Model Selection, 40 Comm. Stat.—Theory & Methods 159, 160 (2010). This Note’s dataset is not large, so from a mathematical standpoint, its preference for logit is inconsequential. From a practical standpoint, one reason for preferring logit over probit is interpretation. Logit models give log odds ratios, which can be converted into odds ratios. Probit models give differences in z-scores. Odds ratios are easier to understand. See Karen Grace-Martin, The Difference Between Logistic and Probit Regression, The Analysis Factor (May 12, 2017), https://www.theanalysisfactor.com/the-difference-between-logistic-and-probit-regression/ [https://perma.cc/ER2H-RSJD] (making the same observation). ↑

- .Smelcer et al., supra note 49, at 832 tbl.1. ↑

- .This Note takes this data from Standard 509 Information Reports, Section of Legal Educ. & Admissions to the Bar, ABA, http://www.abarequireddisclosures.org/Disclosure509.aspx [https://perma.cc/3AWS-M9H5]. ↑

- .LSAT scores cannot be used on their own because the “distance” between one-point increments is inconstant. The LSAT is scored on a normalized scale from 120 to 180, where 10 points is approximately equal to one standard deviation. Memorandum from Lisa Anthony, Senior Research Associate, to LSAT Score Recipients Regarding June 2014 – February 2017 LSAT Score Distributions (June 20, 2017), https://www.lsac.org/sites/default/files/legacy/docs/default-source/data-%28lsac-resources%29-docs/lsat-score-distribution.pdf [https://perma.cc/5A5N-UVWF]. Thus, the “distance” between one-point increments at the middle of the distribution (around 150) differs from the “distance” between one-point increments on the tails of the distribution (around 120 and 180). Using an LSAC chart to convert LSAT scores into percentiles is equivalent to undoing the normalization of LSAT scores. One-percentile increments are a (more) constant measure of performance than one-point increments, wherever one stands on the scale. ↑

- .Smelcer et al., supra note 49, at 832 tbl.1. ↑

- .See generally Rollin Brant, Assessing Proportionality in the Proportional Odds Model for Ordinal Logistic Regression, 46 Biometrics 1171 (1990) (explaining the proportional odds assumption and the Brant test). ↑

- .One might reasonably interpret the significance of clerkship experience in one of two ways. On one hand, it is possible the ABA committee values former federal appellate clerks for their clerkship experience per se—that is, having been an appellate clerk makes an individual a more attractive nominee. On the other hand, it is also possible this Note’s clerkship variable indirectly measures certain characteristics or attributes, unobserved in this Note, that both appellate judges and the ABA committee find attractive—that is, having been an appellate clerk is not valued per se; rather, the same characteristics or attributes that make an individual an attractive clerkship applicant (e.g., strong writing abilities or maybe a good personality) also make the same individual an attractive judicial nominee years or decades later in the individual’s legal career. On this second interpretation, this Note’s clerkship variable would highly correlate with such unobserved (and perhaps unmeasurable) characteristics or attributes. The clerkship variable would indirectly “get at” personal characteristics or attributes that both federal appellate judges and the ABA committee like. It is unnecessary here to adopt one interpretation (clerkship experience ABA rating) or the other (unobserved characteristics clerkship experience; unobserved characteristics ABA rating). ↑

- .By holding the variables for Obama and Trump nominees at their means, Figure 2 shows the hypothetical of an individual who has been partially nominated by three different presidents. Of course, such a nominee is impossible in reality. However, there is a theoretical justification. Figure 2 shows how an “average” nominee would perform, divorced from any nominating president. It is as if the ABA committee were sitting behind a veil of ignorance, not knowing the identity of the president who has put forward a particular nominee. ↑

- .In statistical terms, this Note cannot reject, with at least 95% confidence, the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between partisanship and the ABA rating that an appellate nominee receives. ↑

- .See supra notes 43–57 and accompanying text (discussing past studies of ABA ratings). ↑

- .Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary, supra note 14. ↑

- .Anonymous source. ↑

- .E.g., WSJ Editorial Board, supra note 7. ↑

- .Alder & Stanzione, supra note 5. ↑

- .This Note’s null finding undermines the empirical claim that the ABA’s ratings exhibit a partisan bias, but it should not be understood to undermine the normative claim that the ABA’s privileged position is unfair. Recently, scholars have recommended the creation of a public body that would perform an evaluative function similar to the function that the ABA judicial committee privately performs. See, e.g., Grant H. Frazier & John N. Thorpe, A Case for Circumscribed Judicial Evaluation in the Supreme Court Confirmation Process, 33 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 229, 253 (2020) (recommending the creation of a Judicial Council, composed of one judge from each U.S. court of appeals, that would evaluate nominees to the U.S. Supreme Court); Kenneth S. Klein, Weighing Democracy and Judicial Legitimacy in Judicial Selection, 23 Tex. Rev. L. & Pol. 269, 298 (2018) (recommending that the United States adopt a European-style “civil-service model” for appointing federal judges). Of course, many U.S. states have already established public commissions to evaluate candidates for state judgeships. Methods of Judicial Selection: Judicial Nominating Commissions, Nat’l Ctr. for State Courts, http://www.judicialselection.us/judicial_selection/methods/judicial_nominating_commissions.cfm?state= [https://perma.cc/5JFD-8493]. ↑