Coordinating Injunctions

Introduction

For a tense six months, it seemed possible that the Trump Administration would be ordered to do the impossible. A clash of injunctions from different federal courts seemed imminent, one commanding it to continue part of a program inherited from the Obama Administration—and another commanding it to halt the program, full stop. In early 2018, district courts in California and in New York issued matching preliminary injunctions ordering the Government to continue renewing Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients, thus disallowing the Government from canceling DACA altogether.[1] But by late that summer, it seemed fairly obvious that a district court in Texas was going to rule that DACA was unlawful to begin with and therefore must end.[2] In the meantime, a district court in Maryland found nothing legally wrong with the Government’s rescission,[3] while another across the Potomac in D.C. made the opposite ruling that the rescission should be vacated as unlawful.[4] In this turbulence, everyone braced for a chaotic landing.

And yet the danger was averted. By the time the Supreme Court granted certiorari on the DACA cases nearly a year later, the Government was operating under what turned out to be a neatly matching set of judicial orders. This was not because the district courts had limited their orders to specific parties or geographies. To the contrary, these orders were held up by all as prime examples of so-called nationwide or universal injunctions.[5] And it was certainly not because the judges agreed about the legality of either DACA itself or its rescission. To the contrary, the judge in Texas accepted the Government’s arguments that DACA was unlawful; and besides, even those courts ruling against the Government diverged on the ideal scope of relief. Nonetheless, a steady state had emerged that lasted for more than a year: two concurrent injunctions were in effect from the judges in California and New York, identical in scope; these orders were matched, in effect, by a partial stay of vacatur by the judge in D.C.; the judge in Maryland had issued no order at all; and despite his views on the merits, the judge in Texas found reason to deny a contradictory injunction.[6] No appeals court disrupted this arrangement.[7]

How can such consonance emerge among federal judges expressing very different views and, in fact, making contrary rulings? The risk of conflicting injunctions is a familiar beast.[8] It is recognized in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure as a rationale for involuntary joinder or even mandatory class actions.[9] In the discourse on nationwide injunctions, its shadow is invoked as a reason not to grant broad relief.[10] And yet, tracking down actual sightings of this beast has not been easy.[11] The alignment that appeared in the DACA cases seems not to be any sort of rare exception, even if it may be lauded as an exemplary occurrence of judicial comity.

This Article suggests a way of thinking about the threat of conflicting injunctions, addressing both “How do judges always seem to avoid this problem?” and “How should judges avoid it?” As Part I will elaborate, the starting point is to see the situation facing such judges as a common decision problem known in the social sciences and in legal scholarship as a coordination game. Here is an example: Imagine that on a single-lane road, one car is heading east and another west. As they approach each other, the question arises, “Who keeps going and who yields?”[12] Each would prefer the right of way. If neither yields—disaster. And yet, if both politely pull over, neither is satisfied and the question iterates, “Now, who goes and who yields?”[13] What each driver does depends on what he expects the other to do, and so the situation is resolved when each driver’s expectation happens to align with the other’s decision: one goes (expecting the other to yield), and one yields (expecting the other to go). Altogether, we know there won’t be a crash; instead, one and only one car will yield. But which? And how will the drivers’ expectations converge about who goes and who yields?

In the judicial coordination problem, one might imagine two judges with parallel cases. Each is on the verge of issuing a preliminary injunction that would clash with the other’s. Each has the option to stay her own order (that is, to yield). If both issue injunctions—disaster. Each would rather yield than clash. And yet, it is unsustainable for both to yield, as each feels compelled to grant relief to the deserving party in her own case if the other judge is going to yield anyway. Whether she does so depends on what she expects the other judge to do. And so, here we are again: We know this situation won’t result in a clash of injunctions. But how will the judges know who should go and who should yield?

A classic solution to such collective indecision is to create a set of shared understandings—call it a convention—that allows one of the possible resolutions to become the obvious focal point around which everyone’s expectations can align.[14] For example, everyone knows that the first car to flash its lights will yield. And so, if the eastbound car flashes its lights first, it now expects the other to go (and so it had better yield), and the westbound car now expects the other to yield (and so it might as well go). The effectiveness of such a convention is due neither to sanctions nor to binding authority. Rather, it works simply by creating compatible expectations about what others will do. That is enough to achieve coordination.[15]

And thus we arrive at my second task in this Article, which is to propose such a shared convention for judges facing a potential clash of injunctions. I will do so by articulating a principle for judges to adopt when they find themselves in such a situation—a principle for coordinating injunctions.[16] Any such principle should be intuitive and easy to imagine,[17] and it should sound in judicial integrity and comity. What is needed for it to work, after all, is not only for a judge to be willing to adopt the principle herself but also for her to expect that other judges will adopt it too.

Here is the proposed principle: Each district judge should issue or stay her injunction in accordance with the outcome she thinks most district judges would choose.[18] She should still express her views on the merits, of course, and specify the exact injunction she would issue (if any), were there no risk of conflicting injunctions. Yet, because she recognizes that the risk is real, she must also make a further issue-or-stay decision.[19] If her intended injunction would achieve the outcome that she thinks most district judges would try to achieve if they were ruling on their own, taking any appellate guidance into account, then she should issue it.[20] But if her own injunction is incompatible with the outcome likely favored by the majority, she should stay it.[21] Her role is to implement that outcome, or else not get in the way. And she should also explain in her opinion why her own position aligns with or departs from her estimate of the majority view—much as she would explain (under existing practice) why her position might not be affirmed by the circuit court when she is ordering a stay pending appeal.

This majority principle has several advantages, as Part II will detail. First of all, it is a most natural answer to the question, “What would we end up doing if we all decided this together as a group?” Going with the majority view, needless to say, is a thoroughly familiar approach throughout the federal courts.[22] More generally, following the principle entails taking the views of other judges into account in a way that promotes ideals of comity, parity, and collegiality among judges. Together, these intuitive qualities make it a salient and attractive focal point for the judicial coordination problem,[23] one that can smooth the judges’ paths toward a stable set of consonant injunctions and stays.

But wait—if federal judges are already doing rather well in avoiding conflicting injunctions, what’s the problem? There remains the issue of how to converge on the better outcome. Even if we are sure that judges will avoid conflicting injunctions by somehow finding a stable outcome in which some of them yield, one such equilibrium might be superior to another.[24] Here, the proposed principle offers both the substantive and procedural benefits of converging on an outcome that likely reflects the true majority view, including possibly greater legitimacy. Part II will elaborate on the advantages, as well as potential difficulties, of this approach by comparing it with possible alternatives.

Most notably, the majority principle compares favorably against an individualistic default in which each judge acts as if there were no other parallel cases. Under the proposed principle, judges with diverse views will have a better chance of acting in alignment from the very beginning, for the simple reason that their best guesses about the majority view are probably more similar than their individual views.[25] (This may also translate into less reason for forum-shopping.) Moreover, if any difference appears, convergence should occur more smoothly for two reasons:[26] First, a course correction would not signify abandoning one’s own view of what is right, but rather updating one’s best guess at the majority view. Second, if it becomes apparent which judges’ initial guesses are the outliers, all judges will then know who should course-correct and who should hold the course.[27]

Part III highlights one important reason why the coordinated outcomes we already observe might not be the result of such a collectively informed process of equilibrium selection. Consider this scenario: One judge decides first. Then another, and another. Even with cases brought around the same time and running in parallel, judges are not generally issuing orders simultaneously. And once one judge has issued an injunction, there is pressure on later judges to act consistently with it (issuing a matching injunction or staying one that is incompatible) given the need to avoid a clash. One might notice that in the DACA cases, the resulting set of coordinated orders exactly matches the injunction issued by the first judge.[28]

The result will still be coordinated and disaster still averted, but now it is due to a path dependence in which all other judges match or avoid clashing with the first injunction issued. I will propose that, in taking on such a responsibility, any judge who thinks she might be the first to issue an order should adopt the same principle already described—acting consistently with her best guess of what a majority of the relevant pool of district judges would view as the better outcome. Doing so becomes an even stronger expression of comity in this sequential story, for she would in effect be disavowing her own first-mover advantage relative to her colleagues. (This approach should also reduce incentives for forum-shopping litigants to race to the courthouse.)

In an appropriate case, this first judge might even stay her own injunction while clearly expressing what she would do, as she awaits similar expressions from her colleagues in the parallel cases. In essence, she would be acting as if every court were deciding at the same time, a posture of symmetry that resonates with ideals of collegiality and parity.[29] Her first‑mover advantage then becomes a form of leadership in announcing a comity‑based convention for others to adopt.[30]

Part III will also address the role of appeals courts in reviewing the decisions of district judges who are applying the majority principle—including what happens when there is a circuit split on the underlying merits. It will then acknowledge the limitations of this Article’s analysis, including the crucial assumption that the judges involved are averse to conflicting injunctions. Conventions have their breaking points, and this one is no exception: under certain conditions it won’t be much use. The Conclusion then entertains the thought that some approximation of the convention proposed here may be what some courts are already doing.

I. The Judicial Coordination Problem

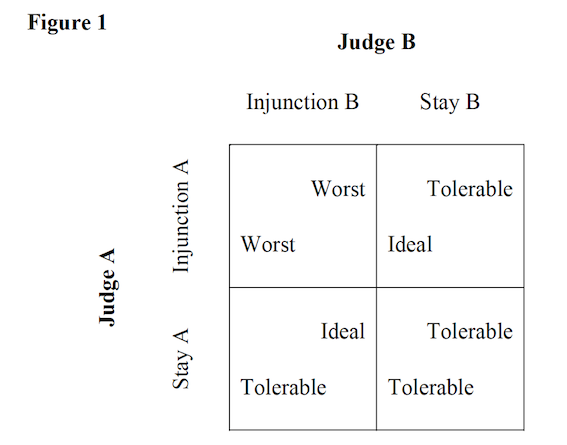

Consider this scenario: Two judges with parallel cases are each on the verge of issuing a preliminary injunction, and these injunctions will conflict if issued. Each judge will write an opinion ruling on all the prerequisite merits questions and articulating the injunctive relief she believes is warranted. In light of the potential conflict, however, each judge faces the additional question, “Should I issue this injunction, or should I stay it?” In each judge’s view, the ideal outcome is for her injunction to be issued while the other’s is

stayed. A tolerable outcome is for her to stay her own while the other’s is issued. It is also tolerable if both judges stayed, leaving in place the current state of affairs. And the worst result is a clash of conflicting injunctions.[31]

This Part elaborates on how the structure of such a problem fits what is commonly known in the social sciences and in legal scholarship as a coordination game.[32] The following analysis will cover the scenario above as well as several variations. It then reviews the standard logic of such a coordination game, showing that one of two stable outcomes is likely to emerge; in each, one judge issues an injunction, and the other stays. What is unlikely to be observed due to its inherent instability, however, is a set of conflicting injunctions.

A. The Structure of the Problem

The outcomes of the four possible combinations of choices by the two judges, in the scenario described above, are shown in Figure 1. Judge A’s options are shown on the vertical axis, and Judge B’s options are shown on the horizontal axis. Judge A’s view of each outcome is listed on the lower left of each box, Judge B’s on the upper right.

Readers may recognize this as a particular coordination game (commonly called the hawk–dove game) often used to represent situations in which the key question is, “Who yields?”[33] The literature on this game is well-developed, thanks to its applicability to many issues in economics, political science, sociology, and evolutionary biology.[34] An early, rich, and influential analysis of such situations is that of Professor Thomas Schelling, who emphasized the crucial role that shared expectations of behavior—whether one calls it a convention, norms, precedent, etiquette, culture, or as he did, a focal point—can play in enabling coordination.[35] In legal scholarship, Professor Richard McAdams has thoroughly studied this game as one means by which the law might promote coordination among parties with conflicting interests in a variety of contexts,[36] and his joint work with Professor Janice Nadler has offered experimental evidence of the effectiveness of supplying a focal point.[37]

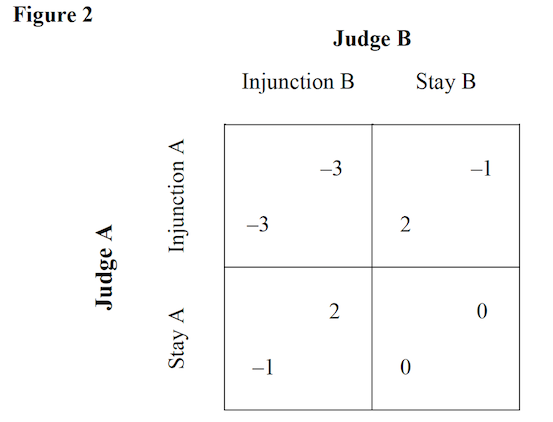

For present purposes, there is no need to put numerical values on these outcomes. What matters to the analysis is the relative ordering of the outcomes in each judge’s view—“ideal” is better than “tolerable,” which is still better than “worst.”[38] But for a stylized illustration of what such an ordering might mean, one might imagine assigning point values to those labels, as seen in Figure 2. Setting zero to represent the initial situation, the judge gains two units of value if the right outcome occurs because her own injunction goes into effect, she loses one unit of value if the wrong outcome occurs because the other judge’s injunction is in effect, and she loses three units of value if there is a clash of injunctions. For Judge A, the resulting value is thus 2 when she issues her injunction while Judge B stays, an outcome we can call {injunction A, stay B}. It is −1 if she stays while Judge B issues his injunction, in {stay A, injunction B}. It is 0 in {stay A, stay B}, where both stay. And it is −3 in {injunction A, injunction B}, where the judges issue conflicting injunctions. These are listed in Figure 2, as are the corresponding amounts for Judge B.

Two variations with different illustrative point values may be worth mentioning—showing how the same setup can represent a range of situations with the same underlying logic. In some cases, a judge might believe that the other judge’s injunction actually makes things somewhat better than the initial situation (in Figure 2, the −1 could be replaced by a positive value of 1), though not as much as her own injunction would do. Or in some cases, a judge might believe that the other judge’s injunction is no better or worse than the initial situation (in Figure 2, the −1 can be replaced by 0 for that judge); for example, the injunction requested from one of the judges may be one that preserves the current state of affairs. In terms of Figure 1, these variations can be seen as allowing for gradations of the meaning of “tolerable.”

What these illustrations have in common is that, for each judge, the ideal is still to issue her own injunction while the other judge stays, and the worst is still the clash of injunctions. This relative ordering is what is crucial for the present analysis (not the illustrative point values), and no doubt the reader can imagine further variations that meet these simple conditions.

Given the assumption of this relative ordering, both judges would prefer any other outcome over the one with conflicting injunctions. Thus, if Judge B expects Judge A to issue her injunction, then he would prefer to stay because he prefers {injunction A, stay B} to {injunction A, injunction B}. And the same logic applies for Judge A. But both judges would also prefer to issue an injunction if the other is expected to stay. If Judge B expects Judge A to stay, he will issue his injunction because he prefers {stay A, injunction B} over {stay A, stay B}. And the same logic applies for Judge A. In this sense, both {injunction A, injunction B} and {stay A, stay B} are inherently unstable. Should either of these unstable outcomes happen to materialize or seem imminent, at least one of the judges would prefer to switch to a different choice.[39]

By contrast, the {stay A, injunction B} and {injunction A, stay B} combinations are stable and self-reinforcing. Once the judges have arrived at either combination, by chance or by design, neither will have any reason to switch on her own. In fact, each has good reason to hold the course. (Such a combination is known in the literature as a Nash equilibrium.)[40] Each judge would switch only if she expected the other judge to switch too. In effect, to depart from such a stable outcome, the judges would have to do so in concert.

B. The Rarity of Conflicting Injunctions

There is good reason to focus our attention on combinations that are stable and self-reinforcing the way that {stay A, injunction B} and {injunction A, stay B} are. As a matter of predicting outcomes, these stable equilibria tell us where things are likely to end up (after some initial adjustment if needed).[41] This is because judges maintain control over their injunctions and stays, and they can modify them at any time.

Imagine, for example, that the two judges each choose initially to stay their own injunctions. They write opinions expressing their views of the merits and articulating the relief they believe to be warranted; but their injunctions are stayed, maybe out of an abundance of caution, maybe out of respect for their colleague’s parallel proceedings, or maybe out of an interest in hearing what the other judge has to say. This initial position is {stay A, stay B}. This is tolerable for both, but Judge A would prefer to switch to issuing her injunction if Judge B is going to stay anyway. Judge B is thinking the same thing about his own injunction. Accordingly, one or both of them will soon lift the stay. If only one judge does so, they have arrived at a stable outcome. If both happen to do so at the same time, the worst outcome might appear but only for a moment before one yields—and then they arrive at a stable outcome.

By the same logic, we also know where things are not likely to end up: with conflicting injunctions. The coordination game described in this Part is a structured story in which, because judges will yield if necessary, conflicting injunctions do not persist. Even if they might occur for a moment (or seem imminent), we know that one of the judges will soon yield. What we don’t know is: which one?

II. The Majority Principle

So far, this Article has set out an intuitive, even self-evident, account of why conflicting injunctions are rarely seen: they are inherently unstable outcomes if judges would rather stay their own injunctions than allow such a clash.[42] Yet, averting a clash is only half of the problem posed by the risk of conflicting injunctions. Because there are two stable and self-reinforcing outcomes (each with one judge issuing an injunction and the other judge staying), the question arises: Which of the two will occur? Which injunction will be issued and which stayed? This descriptive ambiguity also implies normative possibility: Is there a way to tip the odds towards the better of the two outcomes? And is there a way to smooth the path toward that equilibrium?

By way of addressing these questions, this Article now proposes a principle for judges to apply when facing such a coordination problem.[43] It is a principle that enjoys independent appeal as a matter of comity, seems intuitive enough to serve plausibly as a shared expectation of what other judges will do, steers the group of judges toward the stable outcome that brings the likely advantages of accuracy and legitimacy, and encourages convergence on this outcome by lowering the hurdle of justification for those judges who will need to stay their own orders to avoid the clash of injunctions.

A. Applying the Principle

This is the principle: Each district judge should issue or stay her injunction in accordance with the outcome she thinks most district judges would choose. Specifically, she should make a best guess at the majority view within the population of district judges who could in theory hear overlapping cases and issue conflicting injunctions.[44] Depending on the nature of the litigation, this may be a nationwide pool or some subset limited by geography or jurisdiction.

Going with the majority view among the relevant judges may sound like a rather obvious thing to suggest—and I would hope so. Because majority rule is already so familiar within the federal judiciary, this principle is an instantly salient answer to the question, “What would we end up doing if we all decided this together as a group?”[45] Moreover, in some instances, thinking about what other judges would do might already be a part of a judge’s process in deciding what she herself will do. For present purposes, the more obvious this principle seems to be, the better it will do in creating a focal point for the coordination problem—that is, in creating shared expectations identifying who should go ahead and who should yield.

It should be emphasized that the principle concerns only the decision about issuing or staying an intended injunction. Even while applying this principle, each judge should still express her own views on the merits of the case and articulate the relief that she herself would order (if any) were she the sole judge with such a case. But for her decision whether to issue or to stay her intended relief, the principle counsels her to imagine what most district judges in the relevant pool would view as the better outcome (if they were ruling on their own). If she believes that her own view of the better outcome accords with her best guess of this majority view, then she should issue her injunction to achieve that outcome. If instead her own view of the better outcome departs from her best guess of the majority view, then she should stay her incompatible order—explaining that despite her own reasoned views, she is nonetheless staying it in light of the presence of parallel cases and the risk of conflicting injunctions.

The advantages of this majority principle, as well as potential difficulties in applying it, might be best illustrated by comparing it with possible alternative principles. The most immediate and most useful comparison is between this principle and the default approach in which each judge acts solely based on what she believes to be the better outcome (as if there were no other cases and hence no possibility of conflicting injunctions). The following analysis will begin with this comparison before addressing others.

B. Implementing Comity

The first relative advantage of the majority principle is that it serves comity and collegiality in a situation where such concerns are at the fore. By definition, the majority principle takes account of the views of other judges, whereas the individualistic default approach does not. This is true even if a judge trying to follow the majority principle is really thinking in a heuristic way about where she stands relative to other judges, rather than counting votes on an imagined en banc court of all her relevant colleagues. However she approaches the task, she would be equalizing her role with other judges in a way that resonates with notions of parity among judges of the same rank.

On the flip side, one possible difficulty is that the principle would seem to entail research into what other judges have done in similar cases. Looking into what other judges have done is typical legal research, a familiar task;[46] and yet, the amount of research necessary might multiply (in a case with broad geographic reach) if the relevant circuits differ on applicable norms or doctrines for injunctive relief, or if there is a circuit split on the underlying merits. As a practical matter, however, the parties would bear the initial burdens of briefing this issue—an effort that likely overlaps with the research and argumentation they would already have prepared in briefing the court about the suitable remedy in the first place.

Moreover, many federal judges are regularly in touch with their colleagues around the country—and even more so within a circuit or district—through their work on Judicial Conference committees,[47] sittings by designation,[48] and other collaborations and collegial communications. In these and other ways, a judge may have gained a sense of the various judicial philosophies among a wide range of colleagues, allowing easier and more accurate estimation of where she herself stands in relation. The more relevant difficulty for district judges might be the process of getting used to taking other judges’ views into account—a daily practice for circuit judges who must write opinions that satisfy a majority on a panel, but maybe not as habitual for most district judges except in guessing what the circuit court will say on appeal.

A greater obstacle may be that the majority principle will require some judges to announce that they are staying relief based on what other judges would do. No doubt this is an unpleasant thing to have to tell the deserving parties in one’s own case. But it is possible to explain forthrightly that, while such a stay is a hardship, it is justified as an exceptional measure by the presence of parallel cases, which create a risk of conflicting injunctions. After all, explaining such a necessity is not far removed from the familiar judicial task of ordering a stay of relief pending appeal.

Notably, both a stay pending appeal (under existing practice) and the majority-respecting stay (proposed here) require superimposing a further calculus upon the original weighing of equities that justified injunctive relief in the first place.[49] Doing so in either context recognizes that another court (or set of courts) might weigh those original equities differently—and thus,

undue hardship may end up befalling the “wrong” party if this court’s injunction is issued—thereby forcing the question of who should bear the interim hardships until the uncertainty is resolved.

C. Smoothing the Path

The main practical advantage of the majority principle is that it may promote smoother convergence to a well-coordinated, stable, and self-reinforcing outcome. This is for three reasons. First, judges’ best guesses about the majority view are probably more similar than their individual views. (Think of the difference between asking everyone, “Do you think more people are left-handed or right-handed?” versus “Are you yourself left-handed or right-handed?”) Thus, judges with diverse views will have a better chance of acting in alignment from the get-go if they are following the majority principle than if they are acting based on their individual views. This is not to suggest that there will be instant unanimity, as it seems plausible that a judge’s best guess about the majority view may tend to resemble her own view. But the formal shift in perspective allows some judges to openly address the gap between their own views and those of most other judges (“look, it’s not me—it’s them”). One might speculate that such a gap would be most readily admitted by those judges who already see themselves as more independent-minded or even iconoclastic; if so, then the principle might make the most difference where it is most needed.

The second reason relates to the dynamics of convergence. As the judges make their initial guesses, it may become apparent which guesses are the outliers, if any. Seeing this, all judges will know who should course-correct and who should hold the course.[50] For example, if four out of five judges initially guessed that a certain outcome would be the majority view, then it becomes fairly obvious that the one judge who guessed otherwise should alter her order.[51] And if there is a seeming tie among the guesses, a tiebreaker may be based on the relative strengths of the guesses, as seen in the articulated reasoning accompanying the judges’ decisions. Each judge is not only announcing a guess but also explaining it, and the explanation may evince the judge’s degree of certainty.[52]

By contrast, under the individualistic approach, there is much less useful information to be gained from seeing what other judges have decided to do—precisely because the question there is “What do I believe is the better outcome?” Perhaps in a very close case, observing other judges’ choices could lead a judge to reconsider her own view. And yet, a judge may well surmise that the particular judges who actually have these parallel cases are a subset forum-shopped by interested parties. Accordingly, the judge might discount the signals from these selected colleagues’ individual positions (imagine if they were all left-handed) while having less reason to discount their best guesses about the majority view (as the left-handed judges would still say that most people are right-handed).

Finally, there is a more subtle way in which the majority principle promotes smoother convergence. Imagine that the judges in the parallel cases turn out to have different best guesses about the majority view and thus are initially aiming at different outcomes. At this point, a course correction is necessary from one or more judges. Crucially, the initial decision of each judge reflects her best guess about the majority view, not her own view. And thus, altering that decision would not signify abandoning one’s own view of what is correct—but instead, updating one’s estimate of the majority view. This shift in framing makes it easier for the judge to justify the change to the parties and the public, and maybe to herself too.

Further substantive and procedural benefits follow from this process of convergence among judges applying the majority principle. First, compiling the judges’ best guesses of the majority view may lead to greater accuracy in predicting the true majority view, relative to compiling their individual views.[53] It may thus reduce the chances of disruptive alterations later, either as new district judges weigh in or as the appeals courts take up the cases.[54] Moreover, it may be easier for a sense of legitimacy to attach to such an outcome than one that reflects a judge’s individual view.[55] Such relative legitimacy may be useful for fostering public acceptance or understanding. It may also ease acceptance by fellow judges.[56] After all, by definition, this approach aims to minimize the number of judges who would disagree.

D. Alternative Principles?

Thus far, the comparison has been between the majority principle and the default approach. But other conventions are also possible, and it is worth examining three variations that may also be salient enough to serve as plausible focal points in the coordination game. Despite some salutary qualities to each, however, none seems as promising overall as the majority principle already proposed.

The first alternative is a sort of variation on the majority principle in which each judge is making a best guess only about the views of the specific judges who are actually deciding existing parallel cases (rather than an imagined majority view among all district judges who could in theory hear an overlapping case). At first blush, it may seem much easier for a judge to guess what a handful of known colleagues would believe to be the better outcome than to imagine the larger universe of relevant district judges. But the specific-judges approach also seems to demand more precise estimation, whereas the original majority principle may invite the use of heuristics,[57] thus easing the task. Moreover, focusing only on those specific judges with parallel cases may reward forum-shopping; it may even spur the filing of more cases before selected judges in order to “stack” that subsample.[58] By contrast, focusing on the whole population of potentially relevant judges should tend to have the opposite effect, reducing the motivation for forum-shopping.[59] And more generally, a population-based guess would not be pushed about by the appearance of newly filed cases or the disappearance of cases dismissed along the way.

Adopting the original majority principle may require greater judicial fortitude, however, if the judges with actual cases were all chosen precisely for holding views known to differ from most judges. Supposing such a lineup of minority-view judges were in agreement with each other, there would be no risk of conflicting injunctions. And yet under the majority principle, all of these judges would be asked to explain that they were staying the relief they believed to be warranted because they were guessing that yet other judges would see things differently.[60] Following the majority principle still entails the advantages noted above, but it may be a lot to ask of judges who already know that they agree with each other.[61] What may be gained by a general commitment to the original majority principle, however, is (again) some reduction in the incentive to forum-shop to these judges in the first place.

A second alternative is for each judge to base her issue-or-stay decision on her best guess of what most judges think the Supreme Court would do. This formulation might seem to combine the advantages of a majority-based approach with a forward-looking awareness that, for some cases, the Supreme Court will have the final say and that the lower courts should be approximating that result from the outset. This formulation seems less useful than the original majority principle, however, for a couple reasons. First, district judges often are asked to do things the Supreme Court generally does not do; for example, it may seem somewhat odd to ask what kind of preliminary injunction the Court would issue.[62] Second, in cases where the Court does have a discernible view relevant to the issue-or-stay decision, then this input is already subsumed in guessing what a majority of district judges would do if one sensibly assumes they would follow the Court’s lead.[63]

A third alternative is that all judges should, out of an abundance of caution or as an extreme version of comity, stay any intended injunctions if there is a chance of a clash, until a definitive resolution is supplied by the relevant higher court. This is just the unstable outcome of {stay A, stay B} already discussed in Part I. It is unstable because each judge would prefer to issue her own intended injunction, feeling compelled to grant relief as long as it will not clash with another order (say, if the other judge is staying anyway). Thus, the intuitive attractiveness of such an all-stay-pending-appellate-resolution approach would tend to be undermined by its likelihood of failure, unless the relevant higher court weighs in fast enough. Moreover, especially in cases challenging a new government action, it probably won’t help persuade district judges to maintain an all-stay holding pattern to argue that such an approach has the special advantage of preserving the “status quo”—for the obvious reason that the whole point of a preliminary injunction is to preserve an earlier “status quo,” the state of the world before this latest government action.[64]

It may thus be more promising to think of an all-stay combination as a sensible, if cautious, starting point for district judges before they themselves collectively shift to one of the stable outcomes, {stay A, injunction B} or {injunction A, stay B}—ideally, based on the majority principle.[65] And such an approach becomes all the more compelling in a sequential version of the problem, a story involving path dependence, which we turn to next.

III. Extensions and Limitations

What if one judge issues an injunction first? Won’t the others feel a need to act consistently with whatever that judge has ordered? And what happens to an equilibrium when an appeals court reverses a district court? This Part addresses these important extensions. It then acknowledges the limitations of this Article’s analysis, including the crucial assumption that judges care enough about conflicting injunctions to want to avoid them.

A. The First-Mover Advantage

Even when parallel cases are brought before multiple courts around the same time, judges do not generally issue orders simultaneously. Thus, some judges will already know what at least one of their colleagues has decided to do by the time of their own decisions. And because of their aversion to a clash of injunctions, there may be a path dependence in which all later judges match (or do not conflict with) that first injunction. One might note, for example, that in the DACA cases, the resulting set of coordinated orders aligns with the specific contours of the injunction issued by the first judge in

California.[66] The judge in New York matched it exactly.[67] After the judge in D.C. declared that vacatur was appropriate (implying relief going beyond the earlier injunctions), he soon clarified that his vacatur was to be stayed in part in a way that again matched the earlier injunctions.[68] Even more dramatic was the decision by the judge in Texas: despite having expressed a view on the merits that DACA itself is unlawful, he nonetheless denied the Government’s request for an injunction ending DACA, thereby averting a clash of contradictory orders.[69]

Path dependence is not inevitable, however, for the simple reason that the first judge (or any judge) can always modify her initial choice. That is why the coordination game described in Part I, in which judges are described as deciding contemporaneously, remains a useful analytical device. And yet, it is also possible that in some cases, the costs of alteration are perceived to be high, say, because that first injunction creates reliance interests or because a shift to a different equilibrium would create confusion.[70] If so, the first injunction may have a sticky quality that pulls later orders into alignment. If nobody expects that initial order to be altered, then such an alignment will be stable; it may be hard to dislodge, unless the judges all agree to change their orders at the same time.

But allowing such a first-mover advantage to be exercised without a higher-level guiding principle seems to invite a twisted mix of forum-shopping and racing-to-a-remedy by strategic parties. And even without such manipulation, the first court to reach the remedial stage might be in that position precisely because it has less of an evidentiary record to grapple with

(say, about the relevant equities and hardships). More generally, information about the universe of parallel cases, and about what is at stake, may accumulate over time.

Thus, I would argue that any judge who thinks she might be the first to issue an injunction should adopt the majority principle.[71] Moreover, she should also be willing to update her guess (if feasible), were it to become apparent that most of her colleagues with parallel cases are guessing differently about the majority view.

Procedural benefits follow. If it is widely known that judges would be applying this majority principle even if they were the first to decide, then the incentives for forum-shopping litigants to race to the courthouse might be reduced. In addition, adopting the majority principle is an even stronger expression of comity by the judge, in this sequential story: she is essentially disavowing her own first-mover advantage relative to her colleagues (even if in fact she retains the advantage) because she is choosing not to impose her own view. Rather, she is offering her best guess of what would happen “if all of us judges were deciding this altogether.”

One might say that her first-mover advantage is transfigured into a form of leadership in norm-creation, as she would also be announcing a comity-based convention for others to follow.[72] Furthermore, this first judge’s willingness to update her own guess (as more information becomes available) would amount to truly relinquishing her first-mover advantage. In effect, it brings the coordination problem back to the simultaneous-move version originally described, restoring a symmetry among the judges that befits the ideals of collegiality and parity.

One way for this first judge both to signal such a willingness to adjust and to enable it as a practical matter is initially to stay her injunction (if any) while also expressing her best guess of the majority view. As other judges do the same, they will all start to see what their colleagues’ guesses are (while any injunctions are stayed). As we know, such an all-stay outcome is unstable. But here, it is intentionally so.[73] From this staging point, the majority principle can guide the judges collectively

toward agreement on who should be maintaining their stays and who should be lifting theirs.

B. Appeals

Appellate review of equitable relief tends to be limited and deferential—and it should remain so when the appeals court is reviewing a district judge’s decision (to issue or to stay her injunction) based on the majority principle. This Article’s general prescription for the appeals courts is to aid, or at least not hinder, the district courts in solving their coordination problem. In particular, appeals courts should respect the district courts’ use of the majority principle. When necessary, they might reinforce its use by encouraging or directing district courts to follow the principle.[74] But the appeals courts should rarely, if ever, upset the stable outcomes that emerge from district courts already coordinating among themselves by following the principle. This can be done even while the appeals courts are fulfilling their own role in law declaration—and thus, even if a circuit split emerges on the underlying merits. For illustrations, consider the following.

Suppose an appeals court rules in a way that leans in favor of a preliminary injunction being issued. If it is affirming a district court that has already issued or stayed such an injunction based on the majority principle, then it should leave that injunction or that stay in place.[75] But if it is reversing a district court that had originally ruled against any relief, then it should remand, in which case the district court would then follow the majority principle in either issuing or staying the injunction implied by the appellate ruling.[76]

If the appeals court rules in a way that leans against relief, there is certainly no worry about creating a conflict of injunctions. For example, suppose an appeals court decides to reverse the tentative merits ruling that supports a district court’s preliminary injunction. On its own, such a reversal does not worsen the risk of conflicting injunctions (at most, it would be lifting an injunction). And if there are matching concurrent injunctions in place, then there should be no change in the real-world outcome because the courts remain in equilibrium.[77] Indeed, this may be a good reason for multiple courts to issue matching concurrent injunctions, as we have seen in the DACA cases.[78]

But a trickier situation arises if the district court being reversed is the only court that has issued the injunction. Now the question arises for any other court that has been staying a contrary injunction whether it should lift its stay (after all, there is no longer a danger of conflicting injunctions). The default answer I propose is “no,” if the stay was put in place based on the majority principle, especially if it remains possible that another district court with a parallel case (and also based on the majority principle) may yet issue an injunction similar to the one erased by the appeals court. But one might also ask whether every other judge should now update her best guess about the majority view based on the appeals court’s ruling. Again, the default answer I propose is “no,” if what was being corrected in the reversal was not the district judge’s guess about the majority view but rather her guess about

that (sole) circuit court’s view on an underlying merits question in that case.[79] An especially helpful appeals court might even make clear in its opinion that it is not disturbing the former.

More generally, this distinction between regulating a district court’s use of the majority principle in its issue-or-stay decision and regulating the underlying merits is what allows the majority principle to continue to be useful even when a circuit split emerges on the latter. Just as district courts can expressly disagree about the merits (or the ideal remedy) even while following the majority principle in their issue-or-stay decisions, so too can circuit courts expressly disagree about the merits (or the ideal remedy) while allowing the district courts to continue following the majority principle.[80]

C. Heterogeneity

An important limitation of this Article’s scope lies in a crucial assumption: that every judge with one of the parallel cases is averse to a clash of injunctions, seeing it as the worst outcome—and in particular, worse than staying her own intended injunction while a different one is issued. In the present story, this assumption is responsible for the inherent instability of a conflicting-injunctions outcome; it is the reason judges always seem to manage to avoid it.

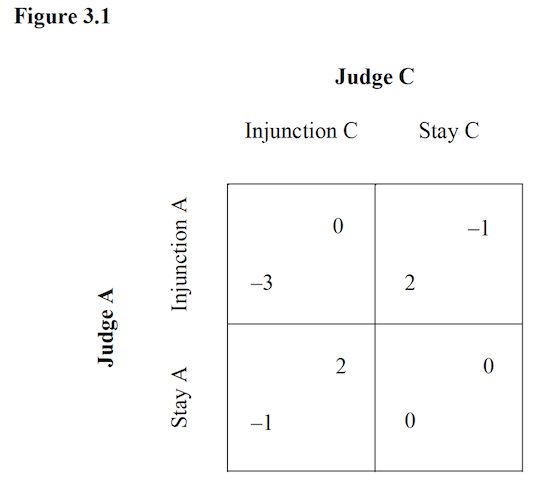

To illustrate what may happen if one judge is not much bothered by conflicting injunctions, compare Figure 2 with Figure 3.1. In the latter, Judge C does not suffer a loss of −3 when there is a clash of injunctions, but rather considers it a tolerable 0. Now, Judge C would always rather issue his injunction, regardless of what he expects Judge A to do.[81] Knowing this, and therefore expecting Judge C to issue his injunction, Judge A would rather stay. A single stable outcome is possible: {stay A, injunction C}. Notice that a clash is still averted, but only because Judge A still cares enough to avert it.[82]

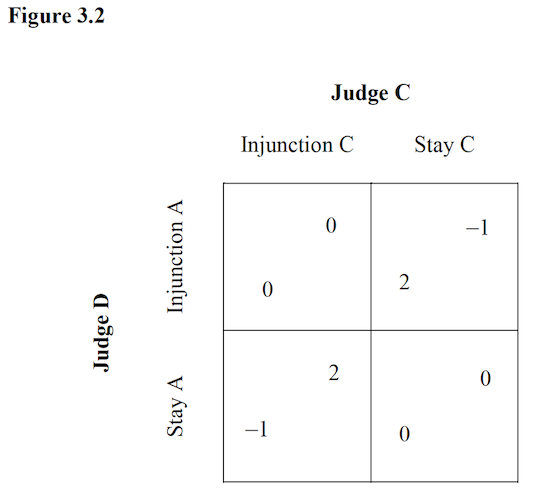

The clash might not be averted, however, if both judges are unbothered by it. In Figure 3.2, Judge C as well as Judge D now consider it to be a

tolerable 0 rather than a loss of −3. Here, the judges would each always prefer to issue an injunction. Accordingly, the only stable outcome is the clash of injunctions.

When one or both judges do not care to avert conflicting injunctions, their situation is no longer a coordination game. There is no need for this Article’s guidance in setting a convention about who yields because either one judge is forced to yield (as in Figure 3.1) or neither judge will ever yield (as in Figure 3.2). Then the question is whether these scenarios are likely to occur. The latter seems implausible given how rarely an actual clash of injunctions is ever observed, even in situations where judges with opposing views have been forum-shopped by plaintiffs with opposing aims. It is not so easy, based on observational evidence, to reject the former story, in which Judge C will always get his way. But I would speculate that contemporary norms among federal judges strongly disfavor such an unyielding posture.

At least, for now. A future reader may well be musing to herself, “comity—how quaint.” But here’s what we see today: an epic surge of nationwide injunctions that has thus far dodged any enduring clashes, with district courts and circuit courts alike showing a willingness to innovate to ensure such consonance, if not for the sake of comity then to avoid the costly confusion of incompatible demands.[83] Even if turnover in the judiciary does bring in an occasional Judge C, and even if interested parties are able to forum-shop to him, his impact might still be tempered by appellate review. This is all the more so, if the majority principle comes to be widely adopted, helping to reinforce the current norms it serves.

That said, there is heterogeneity among judges—in their degrees of aversion to conflicting injunctions, in the strength of their beliefs about certain outcomes being better, and in their willingness and ability to guess at the majority view, among other dimensions. One worthy aim for future work would be to explore alternative approaches that expressly address such variation, especially if the seeming trend towards a more polarized judiciary continues. For example, one might examine the potential role of first-mover injunctions that have the quality of compromises, splitting the difference as a way of ensuring that such an outcome remains more tolerable than a clash of injunctions in every later judge’s view.[84]

Conclusion

One final thought: How do we know that the federal courts, as they seem to coordinate their injunctions without fail, are not already following some approximation of the majority principle proposed here? After all, acting consonantly with the prevailing view among relevant colleagues may seem to many judges a rather obvious way to avoid clashing—one that resonates with comity, mutual respect, fairness, collegiality, and familiarity.

Maybe they are. All the better. The modest service of this Article would then be to help the norm-creation along, by spotlighting this approach and urging judges to articulate it expressly, in hopes of making it still more salient for future courts.

- .Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., 279 F. Supp. 3d 1011, 1048 (N.D. Cal. 2018), aff’d, 908 F.3d 476 (9th Cir. 2018), cert. granted, 139 S. Ct. 2779 (2019); Batalla Vidal v. Nielsen, 279 F. Supp. 3d 401, 437 (E.D.N.Y. 2018), cert. before judgment granted, 139 S. Ct. 2773 (2019). ↑

- .Vivian Yee, Can DACA Survive Its Latest Legal Attack in Texas?, N.Y. Times (Aug. 9, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/09/us/daca-texas-courts-immigration.html [https://perma.cc/2C5Y-9L9A]. ↑

- .CASA de Md. v. U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., 284 F. Supp. 3d 758, 779 (D. Md. 2018), aff’d in part, vacated in part, rev’d in part, 924 F.3d 684 (4th Cir. 2019). ↑

- .NAACP v. Trump, 315 F. Supp. 3d 457, 474 (D.D.C. 2018), cert. before judgment granted, 139 S. Ct. 2779 (2019). ↑

- .See, e.g., Amanda Frost, In Defense of Nationwide Injunctions, 93 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1065, 1077 (2018) (noting that district courts issued nationwide injunctions in the DACA cases); William P. Barr, End Nationwide Injunctions, Wall St. J. (Sept. 5, 2019, 6:37 PM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/end-nationwide-injunctions-11567723072 [https://perma.cc/HA92-KC9K] (using DACA cases as an example of nationwide injunctions); Alan Feuer, Second Federal Judge Issues Injunction to Keep DACA in Place, N.Y. Times (Feb. 13, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/13/nyregion/daca-dreamers-injunction-trump.html [https://perma.cc/CGN6-KTDZ] (characterizing the ruling in one of the DACA cases as a nationwide injunction). ↑

- .Texas v. United States, 328 F. Supp. 3d 662, 742–43 (S.D. Tex. 2018); see also Michael D. Shear, Federal Judge in Texas Delivers Unexpected Victory for DACA Program, N.Y. Times (Aug. 31, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/31/us/politics/texas-judge-daca.html [https://perma.cc/5HFQ-WVZT]. ↑

- .The Ninth Circuit affirmed the district court in California. Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., 908 F.3d 476, 486 (9th Cir. 2018). The Fourth Circuit reversed the district court in Maryland. CASA de Md. v. U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., 924 F.3d 684, 690–91 (4th Cir. 2019). ↑

- .Although the issue has received much attention in recent debates over nationwide or universal injunctions against the federal government, that of course is not the only relevant context. A clash of injunctions could occur—and thus the need for coordination exists—any time more than one plaintiff is asking the courts to issue incompatible orders against the same defendant. This includes cases with private defendants as well as cases in which injunctions are limited in geographic scope (for example, cases limited to federal circuit boundaries or even a single federal district). And clashes remain possible even in cases where the injunctions are “plaintiff-oriented” rather than “defendant-oriented.” See, e.g., Michael T. Morley, Disaggregating Nationwide Injunctions, 71 Ala. L. Rev. 1, 10 (2019) (presenting a taxonomy distinguishing plaintiff-oriented from defendant‑oriented injunctions but recognizing that “[w]hen a case involves indivisible rights, in which it is impossible to enforce the rights of the plaintiff before the court without thereby also enforcing others’ rights as well, a valid plaintiff-oriented injunction will resemble a nationwide defendant-oriented injunction”); id. at 38 (citing Frost, supra note 5, at 1082–84, 1091–92) (offering examples). ↑

- .Fed. R. Civ. P. 19(a)(1)(B)(ii), 23(b)(1)(A). ↑

- .See, e.g., Dep’t of Homeland Sec. v. New York, 140 S. Ct. 599, 600 (2020) (Gorsuch, J., concurring) (condemning “the routine issuance of universal injunctions” as “patently unworkable, sowing chaos for litigants, the government, courts, and all those affected by these conflicting decisions”); Samuel L. Bray, Multiple Chancellors: Reforming the National Injunction, 131 Harv. L. Rev. 417, 462–64 (2017) (discussing the risk of conflicting injunctions “lurking in the background”); Zayn Siddique, Nationwide Injunctions, 117 Colum. L. Rev. 2095, 2143–44 (2017) (suggesting that the risk of conflicting injunctions could be reduced by limiting the geographic scope of remedies to what is “necessary to afford complete relief”). ↑

- .See, e.g., Spencer E. Amdur & David Hausman, Response, Nationwide Injunctions and Nationwide Harm, 131 Harv. L. Rev. F. 49, 52 (2017) (observing that “the risk of conflicting injunctions is vanishingly low”); Frost, supra note 5, at 1106 (maintaining that conflicts are “rare” and pose no “significant problems”); Mila Sohoni, The Lost History of the “Universal” Injunction, 133 Harv. L. Rev. 920, 995–96 (2020) (commenting that the risk of conflicting injunctions is “a risk that rounds to zero”). ↑

- .This illustration is sometimes presented as a problem of cars approaching an intersection with no traffic signals (with interesting variations represented by differences in the structure of the situation). See, e.g., Robert Sugden, The Economics of Rights, Co-operation, and Welfare 34–52 (1986) (setting forth and analyzing the “crossroads game”); Richard H. McAdams, A Focal Point Theory of Expressive Law, 86 Va. L. Rev. 1649, 1704–13 (2000) (analyzing the potential role of law or other focal points in such an intersection game, crediting the original illustration to Professor Sugden). ↑

- .Note that sorting this out can be tricky even when the drivers can communicate: “Please, you first.” “No, you, I insist.” ↑

- .The vast literature on such focal points begins with the classic exposition by Professor Schelling. Thomas Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict 57 (1960) (“Most situations—perhaps every situation for people who are practiced at this kind of game—provide some clue for coordinating behavior, some focal point for each person’s expectation of what the other expects him to expect to be expected to do.”); see also McAdams, supra note , at 1659–66 (recognizing Schelling’s contribution and applying the concept of focal points as a possible mechanism for the law’s expressive effect on organizing behavior). ↑

- .Schelling, supra note , at 54 (“What is necessary is to coordinate predictions, to read the same message in the common situation, to identify the one course of action that their expectations of each other can converge on. They must ‘mutually recognize’ some unique signal that coordinates their expectations of each other.”). ↑

- .Throughout this Article, I will use the term injunction as a shorthand to capture not only preliminary injunctions and permanent injunctions, but also other forms of relief that compel changes in real-world behavior—for example, the partially stayed vacatur by the district court in D.C. in the DACA cases. And for present purposes, I leave alone rulings that do not compel changes to behavior; however, a similar logic to what is articulated here could in theory be applied to inconsistent rulings (in contexts where that may be seen as a problem) as well as to inconsistent obligations (the main concern in this Article). ↑

- .As Professor Schelling notes, “A prime characteristic of most of these ‘solutions’ to the problems, that is, of the clues or coordinators or focal points, is some kind of prominence or conspicuousness.” Schelling, supra note . ↑

- .Naturally, she should have in mind only the population of district judges who could in theory have an overlapping case (and hence could in theory issue clashing injunctions), given the nature of the litigation. For example, in a case involving a nationwide or universal injunction, she would likely be making a (heuristic) guess about where she stands relative to the views of the population of all federal district judges. But for a case involving, say, a statewide injunction, she would be making such a guess about her colleagues within the state. And in some cases the universe of relevant judges for her to consider may depend on limitations of jurisdiction or venue. ↑

- .Stays pending appeal may be the most familiar such practice, in which a federal judge articulates what she believes to be appropriate relief while also staying that relief. Another example is an emergent practice in which a federal court articulates the nationwide or universal injunction that it deems appropriate, while staying it except as to the immediate plaintiff or to a limited geographic area—as seen in the recent “sanctuary cities” cases. See City of Chicago v. Sessions, 321 F. Supp. 3d 855, 882 (N.D. Ill. 2018) (granting a nationwide permanent injunction, but staying its effect outside of Chicago); City and County of San Francisco v. Sessions, 349 F. Supp. 3d 924, 934 (N.D. Cal. 2018), judgment entered sub nom. California ex rel. Becerra v. Sessions, No. 3:17-CV-04701-WHO, 2018 WL 6069940 (N.D. Cal. Nov. 20, 2018) (granting a nationwide permanent injunction, but staying its effect outside of California). ↑

- .Her estimation of the majority view must, of course, consider any appellate or Supreme Court guidance that she thinks might sway most of her relevant district-level colleagues toward a given view. That the principle is formally stated in terms of what most district judges would do is not to suggest ignoring such guidance; rather, it is to recognize that remedial design is a task distinct from deciding merits issues (which are more likely to have appellate guidance) and that district courts may have greater institutional competence than appeals courts in fashioning injunctive relief (as indicated by typically deferential standards of review). See infra subpart II(D). ↑

- .To be clear, the term outcome refers to real consequences—a state of the world—rather than a specific ruling or remedial form. It could be a holding pattern achieved by a preliminary injunction (or allowed by a stay); it could be a longer term steady state achieved by a permanent injunction or by vacatur as final relief; or it could just be the initial state of affairs. There can be multiple ways for a court ruling to achieve or allow the same state of the world. For example, in the DACA cases discussed above, the same holding pattern (in which the Government would continue to process renewals but not new applications) was achieved or allowed by various district courts through formally different rulings or remedies (notably, the two preliminary injunctions, a partial stay of vacatur as final relief, and a denial of a contrary preliminary injunction). ↑

- .These advantages are just as obvious in a scenario where judges can expressly communicate with each other. Recall that even when communication is possible, it is still useful to have a focal point determined by a principle upon which everyone can readily agree. ↑

- .As Professor Schelling observes, “[f]inding the [focal point] . . . may depend on imagination more than on logic; it may depend on analogy, precedent, accidental arrangement, symmetry, aesthetic or geometric configuration, casuistic reasoning, and who the parties are and what they know about each other.” Schelling, supra note . That is, “[p]oets may do better than logicians at this game . . . .” Id. at 58. ↑

- .Cf. Douglas G. Baird et al., Game Theory and the Law 40 (1994) (“Experimental work on coordination games . . . suggests that players do not necessarily choose the Nash equilibrium that is in the individual interests of the parties and in their joint interest as well.”). ↑

- .This seems all the more true if the reason for the district judges’ divergent views is a circuit split on relevant issues. Why the proposed convention is workable even when circuit splits exist (and indeed, why it allows “percolation” to continue) is addressed in the discussion of the role of the appeals courts in subpart III(A). ↑

- .When a judge’s guess about the majority view is highly correlated with his own view, or when judges in the overlapping cases are likely to guess differently at first for any other reason, then a mechanism for smooth course correction becomes all the more important. Moreover, in such circumstances, aggregating different judges’ guesses at the majority view may be more likely (than aggregating their individual views) to result in an outcome that reflects the true majority view. See infra subpart II(C). ↑

- .In subpart II(C), I will say more about why noticing the outliers is a more effective prompt for course correction when judges are guessing at the majority view under the proposed principle, than when judges are expressing their own views under the individualistic default. ↑

- .Even the judge in D.C., whose vacatur seemed initially to go beyond the earlier injunctions, quickly scaled back its effect (using a partial stay) to match the others. NAACP v. Trump, 321 F. Supp. 3d 143, 146 (D.D.C. 2018) (“The Court will stay its order as to new DACA applications and applications for advance parole, but not as to renewal applications.”). The judge explained:The Court is mindful that continuing the stay in this case will temporarily deprive certain DACA-eligible individuals, and plaintiffs in these cases, of relief to which the Court has concluded they are legally entitled. But the Court is also aware of the significant confusion and uncertainty that currently surrounds the status of the DACA program, which is now the subject of litigation in multiple federal district courts and courts of appeals. Because that confusion would only be magnified if the Court’s order regarding initial DACA applications were to take effect now and later be reversed on appeal, the Court will grant a limited stay of its order and preserve the status quo pending appeal, as plaintiffs themselves suggest.Id. ↑

- .The careful reader may notice that this is why the exposition has started with the scenario in which judges seem to be deciding at the same time, rather than starting with the first-come-first-served scenario (even though it may seem more likely). ↑

- .The possibility that this first judge may recognize in retrospect that she has guessed wrong about the majority view (as other judges’ guesses become known) will be discussed in more detail in subpart III(A). Suffice it to say for now that this possibility is a good reason for her to stay, initially. She may not be able to stay, however, if she deems the hardships of even momentarily waiting for other district judges to weigh in to be too great (such as in cases of extreme time sensitivity). Subpart II(B) will spell out how this resembles the balancing analysis required under current practice for a stay pending appeal. ↑

- .A classic statement of this aversion to creating a clash of injunctions is Judge Posner’s:Where different outcomes would place the defendant under inconsistent legal duties, the case for the second court’s not going into conflict with the first is particularly strong. A conflict would place the defendant in an impossible position unless the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case, which it might be reluctant to do if the conflicting decisions, however excruciating for the defendant, raised no issue of general significance—yet might feel obliged to do anyway.Colby v. J.C. Penney Co., 811 F.2d 1119, 1124 (7th Cir. 1987). And the defendant is sure to bring this difficulty to the court’s attention—even when the defendant might believe that the preexisting injunction is wrong. See, e.g., Federal Defendants’ Response to Plaintiffs’ Motion for a Preliminary Injunction at 17–18, Texas v. United States, 328 F. Supp. 3d 662 (S.D. Tex. 2018) (No. 1:18-cv-00068) (arguing in the Texas DACA case that because other district courts have already issued “legally incorrect and overbroad nationwide preliminary injunctions,” this court should refrain from issuing a contradictory injunction or at least stay it, while the defendants try to challenge the earlier injunctions before the Supreme Court). ↑

- .Throughout this Article, the term coordination refers to this framework as applied to the potential clash of injunctions, as distinct from other important questions about overlapping remedies and their interactions. See generally Bert I. Huang, Surprisingly Punitive Damages, 100 Va. L. Rev. 1027 (2014) (proposing ways to reduce redundancy in punitive damages and in statutory damages by running damages “concurrently”); Leah Litman, Remedial Convergence and Collapse, 106 Cal. L. Rev. 1477 (2018) (identifying convergence and spillovers in doctrinal constraints across forms of remedies, undermining the possibility that one form might serve as backup for another); Kyle Logue, Coordinating Sanctions in Torts, 31 Cardozo L. Rev. 2313 (2010) (analyzing possible distortions to deterrence due to redundancy between tort damages and regulatory sanctions). ↑

- .See, e.g., Richard McAdams, The Expressive Power of Law 37 (2015) (explaining that “[t]he game involves conflict with a need for coordination” in that “there is . . . a common interest in avoiding what each regards as the worst possible outcome,” and yet “[t]here is conflict because each equilibrium has unequal payoffs, one favoring Player 1 and the other favoring Player 2”). ↑

- .See, e.g., Paul R. Krugman, Is Free Trade Passé?, J. Econ. Persp., Fall 1987, at 131, 135–36 (using the hawk–dove game to model competition between two firms in the absence of a subsidy); J. Maynard Smith & G.R. Price, The Logic of Animal Conflict, 246 Nature 15, 15–16 (1973) (using the hawk–dove game to understand why conflicts between animals of the same species rarely result in serious injury); Glenn H. Snyder, “Prisoner’s Dilemma” and “Chicken” Models in International Politics, 15 Int’l Stud. Q. 66, 82–93 (1971) (using the hawk–dove game to understand international crises). ↑

- .As Professor Schelling put it:The odd characteristic of all these games is that neither rival can gain by outsmarting the other. Each loses unless he does exactly what the other expects him to do. Each party is the prisoner or the beneficiary of their mutual expectations; no one can disavow his own expectation of what the other will expect him to expect to be expected to do.Schelling, supra note , at 60. ↑

- .McAdams, supra note , at 36–48. ↑

- .Richard H. McAdams & Janice Nadler, Coordinating in the Shadow of the Law: Two Contextualized Tests of the Focal Point Theory of Legal Compliance, 42 L. & Soc’y Rev. 865, 868 (2008); Richard H. McAdams & Janice Nadler, Testing the Focal Point Theory of Legal Compliance: The Effect of Third-Party Expression in an Experimental Hawk/Dove Game, 2 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 87, 108–09 (2005). ↑

- .A technical note: The numerical values are not necessary for analyzing this game in pure strategies (assuming that each judge’s expectation about the other’s strategy is binary rather than probabilistic). Mixed strategies are not considered because they are unrealistic, both as a matter of judicial practice and as a matter of judges’ expectations about what other judges will do. ↑

- .For readers who are fluent in game theory, I should note that although the problem has been characterized so far as a simultaneous-move, one-period coordination game, in my storytelling I am implying that the single period includes enough time for some adjustments before arriving at a Nash equilibrium. I find this to be a convenient shorthand suitable to the context:When the goal is prediction[,] . . . a Nash equilibrium can also be interpreted as a potential stable point of a dynamic adjustment process in which individuals adjust their behavior to that of the other players in the game, searching for strategy choices that will give them better results.Charles A. Holt & Alvin E. Roth, The Nash Equilibrium: A Perspective, 101 Proc. Nat’l Acad. Sci. U.S. 3999, 3999 (2004). An alternative formulation might be to consider such adjustments as occurring during additional periods in an iterated hawk–dove game, but for present purposes, that would complicate the analysis in an unnecessary way. ↑

- .Another technical note: The analysis throughout this Article will be restricted to pure strategies. As mentioned, this is because mixed strategies are unrealistic in this context. Accordingly, attention on equilibria will also be limited to Nash equilibria in pure strategies. ↑

- .See Holt & Roth, supra note (explaining that a Nash equilibrium can be interpreted as a stable point potentially resulting from such adjustments). ↑

- .What might happen if one or more of the judges with parallel cases are not averse to a clash is addressed in subpart III(B). ↑

- .It serves the purpose so crisply described by Professor Schelling: “What is necessary is to coordinate predictions, to read the same message in the common situation, to identify the one course of action that their expectations of each other can converge on. They must ‘mutually recognize’ some unique signal that coordinates their expectations of each other.” Schelling, supra note , at 54. ↑

- .The important distinction between this imagined population of potential judges and the small subset of judges who actually have such an overlapping case before them—along with the reasons to focus on the former group rather than the latter—is detailed in subpart II(D). ↑

- .As Professor Schelling observes: “Most situations—perhaps every situation for people who are practiced at this kind of game—provide some clue for coordinating behavior, some focal point for each person’s expectation of what the other expects him to expect to be expected to do.” Schelling, supra note . It is worth emphasizing that the preexistence of such a focal point can matter even when open communication is possible because the logic that makes a focal point so powerful in a tacit coordination game can also exert a pull on the parties’ bargaining in a coordination game with communication. Id. at 67–70, 73–74. ↑

- .Besides, it is possible that some such research would also be suitable under the individualistic default approach. ↑

- .See, e.g., U.S. Courts, About the Judicial Conference, https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/governance-judicial-conference/about-judicial-conference [https://perma.cc/8JR9-SB8U] (describing the organization of Judicial Conference committees to which judges are appointed). ↑

- .See generally Marin K. Levy, Visiting Judges, 107 Calif. L. Rev. 67 (2019) (discussing the historical development and contemporary practice of visiting judges in the federal court system). ↑

- .The standard approach for deciding whether to stay an order pending appeal is articulated in Hilton v. Braunskill, 481 U.S. 770, 776 (1987). The standard is “(1) whether the stay applicant has made a strong showing that he is likely to succeed on the merits; (2) whether the applicant will be irreparably injured absent a stay; (3) whether issuance of the stay will substantially injure the other parties interested in the proceeding; and (4) where the public interest lies.” Id.; see also Nken v. Holder, 556 U.S. 418, 434–35 (2009) (elaborating on the Hilton standard and its relation to the standard for preliminary injunctions). ↑

- .And they will know that other judges also know, and so forth. Convergence may happen still more smoothly if judges can expressly communicate about selecting one of the stable outcomes. But note that communication is not by itself a substitute for a focal point. (Again, think of the drivers saying “please, you first” and “no, you, I insist.”) Rather, it is more useful to think of identifying a focal point as the aim of the communication—and that having an appealing principle to invoke during the talks may more rapidly bring everyone into alignment. ↑

- .In terms of the coordination game described in Part I, this learning effect solves the iterated question—“Now, who goes and who yields?”—that arises when the judges arrive at an unstable outcome such as {stay A, stay B} or {injunction A, injunction B}. ↑

- .The district judge may of course also express her degree of certainty about her own view of the right outcome (in addition to her degree of certainty about her guess at the majority view). This possibility should ease the potential worry that a judge who stays her own injunction may be misread as signaling a lack of confidence in that remedy. Besides, it is probably a lot less awkward for a judge who believes strongly in her intended injunction (and yet does not wish to create a clash with another injunction) to stay it on grounds of the majority principle, than to try to come up with some other reason (which might well be misread as signaling a lack of confidence). ↑

- .That is, not only are the judges more likely to agree in their guesses of the majority view than in their individual views, as mentioned above, but the stable outcome that results from aggregating such guesses is also more likely to reflect the true majority view. The possible accuracy advantage of observing majority-view guesses rather than individual positions has found some empirical support in a different context: predicting election outcomes by polling voters about their expectations about who will win (analogous to majority-view guesses) as opposed to asking them whom they favor to win (analogous to individual views). See, e.g., David Rothschild & Justin Wolfers, Forecasting Elections: Voter Intentions Versus Expectations, Brookings Inst. 1

(Nov. 1, 2012), https://www.brookings.edu/research/forecasting-elections-voter-intentions-versus-expectations/ [https://perma.cc/KCP9-KRKG] (finding evidence that “polls probing voters’ expectations yield more accurate predictions of election outcomes than the usual questions asking about who they intend to vote for”); Andreas Graefe, Accuracy of Vote Expectation Surveys in Forecasting Elections, 78 Pub. Opinion Q. (Special Issue) 204, 215, 219–20 (2014) (finding that voter-expectation surveys were more accurate than single polls and even combinations of polls). This accuracy advantage may hold even when each individual’s expectations about who will win are correlated, as one might expect, with their own preferences. Id. at 208, 219–21 (noting this problem of “wishful thinking” but still finding that voters’ expectations predicted election outcomes better than their intentions). And “surveys of voter expectations can still be quite accurate, even when drawn from non-representative samples.” Rothschild & Wolfers, supra, at 2. Moreover, the relative accuracy advantage is heightened when the sampled population is small—which one might analogize to the small number of judges with parallel cases. See id. (explaining that “[t]he expectations question performs particularly well . . . when small samples are involved”). ↑ - .Although I have somewhat simplistically labeled such accuracy a “substantive” advantage in part on the assumption that reflecting the true majority view is desirable, it is of course possible to recognize the benefits as mainly “procedural” in the ways noted here—say, if one is agnostic or doubtful about whether majority rule in judicial decisionmaking tends to lead to substantively good results. ↑