Children’s Digital Privacy and the Case Against Parental Consent

Introduction

In February 2020, New Mexico’s attorney general sued Google.[1] In Balderas v. Google,[2] New Mexico alleged that the company is illegally collecting children’s data in violation of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA),[3] the New Mexico Unfair Practices Act (UPA),[4] and the common law privacy tort of intrusion upon seclusion, among others.[5] New Mexico’s attorney general argued that Google had failed to obtain “verifiable parental consent,” as required by COPPA, for the collection, use, or disclosure of personal information.[6]

The lawsuit was initiated based on a Google service called G Suite for Education (GSFE).[7] GSFE provides students with access to services such as Gmail, Google Calendar, Google Drive, and Google Docs, which collect various forms of the users’ data—in this case, children’s data.[8] In November 2020, the U.S. District Court for the District of New Mexico granted Google’s motion to dismiss.[9] Google argued that to attain the verifiable parental consent that COPPA required, it had relied on the schools themselves as intermediaries. It reasoned that to comply with COPPA in “provid[ing] notice and obtain[ing] verifiable parental consent prior to collecting, using, or disclosing personal information from children,” Google only needed to “mak[e] any reasonable effort.”[10]

According to guidelines from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), “schools may act as the parent’s agent and can consent to the collection of kids’ information on the parent’s behalf.”[11] However, in Balderas, this consent also meant consent to access to GSFE’s “Additional Services,” which included minors’ access to services such as “Google Maps, Blogger and YouTube.”[12]

Moreover, the services offered may also include Google Assistant Voice Match and Face Match, both of which require school administrators to “get parental consent for users under the age of 18 to link their Google Workspace for Education accounts to a Google Assistant-enabled device” to be enabled.[13] New Mexico ultimately settled with Google and agreed to dismiss its appeal to the Tenth Circuit.[14]

While the Balderas suit was initiated before the COVID-19 pandemic, the pandemic made the underlying issue even more urgent as a shift to online education became inevitable.[15] With the COVID-19 pandemic, over 1.2 billion children around the world left the traditional classrooms,[16] many of which shifted to online learning in jurisdictions equipped with the necessary infrastructure. The online education market (EdTech) is predicted to reach $350 billion by 2025.[17]

This piece argues that there is a fundamental problem with relying on parental consent in protecting children’s privacy. It is ill-suited as a matter of doctrine and policy and is traditionally disfavored under common law. COPPA was enacted in 1998, during a different era with simpler privacy concerns. In the era of EdTech and artificial-intelligence-enabled tools such as ChatGPT,[18] and voice-and facial-recognition tools, parental consent can no longer meaningfully serve its traditional purpose of protecting the best interests of the child, particularly given the complexity of innovation and potential for breaches of privacy associated with EdTech services. As such, new privacy initiatives at the federal level should also not rely primarily on parental consent but instead offer privacy protection laws that limit the overreach of EdTech companies.

While this piece primarily examines the issue of minors’ use of EdTech tools, the problem of relying on parental consent for minors’ online activities and the use of Internet of Things (IOT)[19] reaches far beyond the educational realm. Today, across the internet from online gaming to other entertainment apps, companies rely on parental consent to offer their products and services to minors. All the while, parents themselves are not sufficiently aware of the potential harms of online activities and their technological complexities to be able to meaningfully consent to them on behalf of their children.

Many scholars have written on the importance of protecting children’s privacy and the inadequacy of boilerplate waivers;[20] however, this work is unique in its approach by comparing parental online waivers to the historical tradition of parental waivers of liability for physical injuries found in the common law of torts. The analysis offered in this piece illustrates that although the law has historically relied on parents to protect the best interests of the child, courts have not been shy in striking down parental consent and waivers of liability for physical injuries of children caused while participating in recreational activities.

When courts deal with parental waivers of liability associated with school activities, they tend to rule in favor of the school and uphold the waiver. This apparent deference to schools does not impact the position that this piece takes. The crucial difference between the traditional status of schools and today’s presence of EdTech in schools is the transactional nature of EdTech-related contracts. If courts uphold certain waivers in schools and in the nonprofit context, it is to protect these nonprofit institutions and insulate them from the heavy burdens of liability. However, EdTech contracts today are commercial and like recreational-activities waivers, which are disfavored by courts. Moreover, parents and schools tend to have a closer relationship than consumers do with manufacturers—parents regularly talk to teachers and administrators, serve on school boards, and volunteer. Further, parents, school officials, and teachers tend to live in the same communities. It is thus understandable why courts would treat recreational activities waivers differently in a school setting and protect the school from liability. How waivers work in this setting does not tells us much about how they should work for distant business transactions between EdTech corporations and schools.

The transactional nature of EdTech activities, this piece argues, undermines the agency of the traditional role of the school echoed in tort cases and the patriarchal role of parents. COPPA’s reliance on parental consent is therefore ill-suited to protect children’s privacy from corporations that are working for profit. The fact that EdTech tools are also becoming a necessity for learning points to another reason why waivers should be discouraged. More broadly, parental consent is no longer an adequate form of minor protection for online activities. As such, Congress and state legislatures should take a stance regarding the protection of children’s digital privacy and incorporate additional measures.[21] Until such legislative change happens, courts should be willing to rely on their own traditions of protecting the best interests of the child and strike down parental waivers in online settings when dealing with children above the age of thirteen and below the age of eighteen—the gap created by COPPA’s limited scope protecting only children under the age of thirteen.

This piece proceeds in the following way: Part I discusses the current landscape of protective measures for children’s online activities, including COPPA. Part II illustrates the courts’ approach towards parental waivers of liability for physical injuries and the relevance of the courts’ treatment of the doctrine of assumption of risk to the consent forms mandated by COPPA. Part III argues that the EdTech industry is different from the traditional role of schools and elaborates on why parental consent is no longer a sufficient tool for the legislative goal of protecting the best interests of the child. By studying two recent cases, Part III also addresses the concern with COPPA’s possible preemption of the common law of torts. It argues that where apps and EdTech do acquire parental consent as a way of insulating themselves from liability for their activities with respect to children between the age of thirteen to eighteen, who are not within the scope of COPPA, courts should strike down those consent forms as against public policy and allow for common law privacy lawsuits until a stronger legislative measure is in place to protect minors’ privacy online.

I. Minors and Privacy: An Overview

Children, as consumers, shape an important aspect of the technological market, and their presence continues to be an inevitable part of the economy.[22] The American legislatures and the common law have historically protected children against threats to their safety.[23] But protecting privacy with emerging forms of surveillance is a new phenomenon. Looking at the early initiatives can be helpful to understand the evolution of privacy protection measures. The Watergate scandal, involving “illegal surveillance on opposition political parties and individuals,” inspired the passage of the Federal Privacy Act of 1974.[24] Congress had relied on a report by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) to draft the Privacy Act of 1974.[25] The report, which also inspired the Fair Information Practice Principles, was “the first comprehensive study of the risks to privacy presented by the increasingly widespread use of electronic information technologies by organizations, replacing traditional paper-based systems of creation, storage, and retrieval of information.”[26] The Act was “later modified by the Computer Matching and Privacy Protection Act of 1988.”[27]

This expansion in legal protection of privacy was accompanied by the passage of the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA)[28] in 1974. FERPA limited the disclosure of educational records for students under the age of eighteen.[29] It vested parents with certain rights for the protection of such records.[30] As governments became more invested in studying the collection and use of personal information, HEW proposed a set of principles that later became “Fair Information Practices.”[31] The HEW report identified five core principles of privacy protection: “(1) Notice/Awareness; (2) Choice/Consent; (3) Access/Participation; (4) Integrity/Security; and (5) Enforcement/Redress.”[32]

Building on the Fair Information Practices, many stakeholders from different sectors, such as policy makers, educators, and parents, showed their support for the passage of COPPA in 1998.[33] COPPA required the FTC to issue regulations regarding children’s online privacy,[34] which went into effect in 2000[35] and were drafted and passed against the backdrop of the notice and consent principals of the codes.

COPPA, as Professor Anita Allen states, “is indeed both privacy law and family law. COPPA is Internet privacy law, governing the commercial sector and the market for information. COPPA is also family law, governing young families in the combined interests of child welfare and parental autonomy.”[36] COPPA is “a governmental effort to compel parental child protection in the best interests of children.”[37]

The law traditionally protects those with limited capacity. For example, “infants and persons suffering from mental infirmity” are two protected classes in contract law.[38] Contracts that minors enter into are voidable, with a few exceptions.[39] The age of majority in common law had been twenty-one, though since 1970 most jurisdictions have adopted eighteen as the age of majority and thus as the age at which individuals have the capacity to contract.[40] These same laws also apply to children contracting in cyberspace.[41] However, COPPA stops short of protecting minors beyond the age of thirteen. According to COPPA, “‘child’ means an individual under the age of [thirteen].”[42]

COPPA’s use of the age of thirteen as its cutoff point appears to be at odds with both the old common law tradition of recognizing twenty-one as the age of capacity and the modern law of recognizing the age of eighteen as the age of capacity. The FTC’s “Frequently Asked Questions” for complying with COPPA take note of the limit of the age protection to the age of thirteen, yet it does not offer any reason for this choice.[43] Instead, it further refers the reader to a different set of guidance documents educating families on protecting themselves and their children from online hackers, threats, and scams,[44] but this publication addresses the possible victims, not the predators. To protect children under the age of thirteen, COPPA asks an operator to:

(a) Provide notice on the Web site or online service of what information it collects from children, how it uses such information, and its disclosure practices for such information (§ 312.4(b));

(b) Obtain verifiable parental consent prior to any collection, use, and/or disclosure of personal information from children (§ 312.5);

(c) Provide a reasonable means for a parent to review the personal information collected from a child and to refuse to permit its further use or maintenance (§ 312.6);

(d) Not condition a child’s participation in a game, the offering of a prize, or another activity on the child disclosing more personal information than is reasonably necessary to participate in such activity (§ 312.7); and

(e) Establish and maintain reasonable procedures to protect the confidentiality, security, and integrity of personal information collected from children (§ 312.8).[45]

A look into the history and context of COPPA can shed light on why its approach falls short when applied to our modern society. COPAA was enacted at a time when the major concern was protecting kids from revealing personal information rather than companies collecting kids’ user data.[46] As such, asking for the permission of a parent to control what a child may say to a third party made sense at the time. The vision, which supported protecting children’s online privacy through parental consent, can be better understood in light of the privacy protection climate in 1998. Back then, children’s access to internet websites was seen as a threat to minors who may recklessly reveal personal information online.[47] The 1998 FTC report to Congress in support of privacy protection for children noted:

Traditionally, parents have instructed children to avoid speaking with strangers. The collecting or posting of personal information in chat rooms and on bulletin boards online runs contrary to that traditional safety message. Children are told by parents not to talk to strangers whom they meet on the street, but they are given a contrary message by Web sites that encourage them to interact with strangers in their homes via the Web. The dangers in the Web environment are heightened by the fact that children cannot determine whether they are dealing with another child or an adult posing as a child.[48]

This report helps capture the sentiment of the time and how parental control of online activities was viewed. Indeed, Google itself was only launched in 1998.[49] The privacy threats and data collection methods used today by corporations were not as pervasive, and many did not even exist yet. Today, with the advent of artificial intelligence tools, for example, children are facing new risks such as becoming subjects of facial recognition apps,[50] a technology that was not widespread in 1998.[51]

Slowly, the practice of collecting information became so pervasive that the FTC initiated a review in 2010 that resulted in COPPA’s 2013 revisions.[52] The revisions were aimed at widening “the definition of children’s personal information to include persistent identifiers such as cookies that track a child’s activity online, as well as geolocation information, photos, videos, and audio recordings.”[53] COPPA also updated its guidelines for businesses’ compliance in 2017 to address new technologies associated with the internet of things (IoT), such as toys and other connected devices.[54]

The U.S. Congress has also been trying to catch up with the inadequacy of the current protective measures. There are several proposed bills in Congress aimed at expanding children’s privacy protection measures. For example, the Children and Teens’ Online Privacy Protection Act was introduced in the Senate in May 2021.[55] The bill extends COPPA privacy protections to minors, defined as someone between twelve and sixteen years old.[56] This bill continues with the tradition of requiring parental consent and does not change that framework.[57]

Another bill was introduced in the Senate in April 2021 called the Clean Slate for Kids Online Act of 2021.[58] The bill would amend COPPA “to give Americans the option to delete personal information collected by internet operators as a result of the person’s internet activity prior to age [thirteen].”[59] This too does not change the parental consent approach.

A more ambitious bill presently under consideration in the U.S. Senate is called Kids Internet Design and Safety Act, or the KIDS Act.[60] The KIDS Act cites to advancements of technologies such as “[a]rtificial intelligence, machine learning, and other complex systems [that] are used to make continuous decisions about how online content for children can be personalized to increase engagement.”[61] It features proposals to address damaging design features, amplification of harmful content, and manipulative marketing.[62]

At the state level, some lawmakers have also taken action. For example, in 2013, California enacted the Online Eraser Law that came into effect in January 2015.[63] The law extends certain cyber protection, most notably the right to erase one’s content from a website,[64] to minors whom the law defines as persons “under the age of [eighteen].”[65] California also has also enacted “The California Age-Appropriate Design Code Act,” which aims to further protect children’s privacy by defining children as consumers “under the 18 years of age.”[66]

However, COPPA contains an express preemption stating that: “No State or local government may impose any liability for commercial activities or actions by operators in interstate or foreign commerce in connection with an activity or action described in this chapter that is inconsistent with the treatment of those activities or actions under this section.”[67]

Several companies have also signed a 2020 pledge called the K-12 School Service Provider Pledge to Safeguard Student Privacy.[68] The Pledge states that “[s]chool service providers take responsibility to both support the effective use of student information and safeguard student privacy and information security.”[69] As it spells out its commitment, it states that the signatories pledge “not [to] collect, maintain, use or share student personal information beyond that needed for authorized educational/school purposes, or as authorized by the parent/student.”[70] However, by carving out an exception for collection when authorized by a parent, the Pledge creates the same boilerplate loophole that plagues COPPA.[71]

As this piece illustrates, minors are granted limited digital privacy protection in the United States, the core of which relies on the notice-and-parental-consent method. Today, however, protecting children’s digital privacy from parents has become a burning issue. The phenomenon of “sharenting” has increasingly become a danger to children’s privacy, personas, and digital identities.[72]

Companies, too, are ill-suited to be trusted with self-regulation for ensuring the safety of minors.[73] For example, in September 2021, a series of files reviewed by the Wall Street Journal revealed that Meta knew how harmful its Instagram platform was for teenage girls yet it failed to act.[74] In a Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation hearing, the “Facebook Whistleblower” Frances Haugen elaborated in detail how “Facebook’s products harm children” and Facebook “has repeatedly misled us about what its own research reveals about the safety of children.”[75]

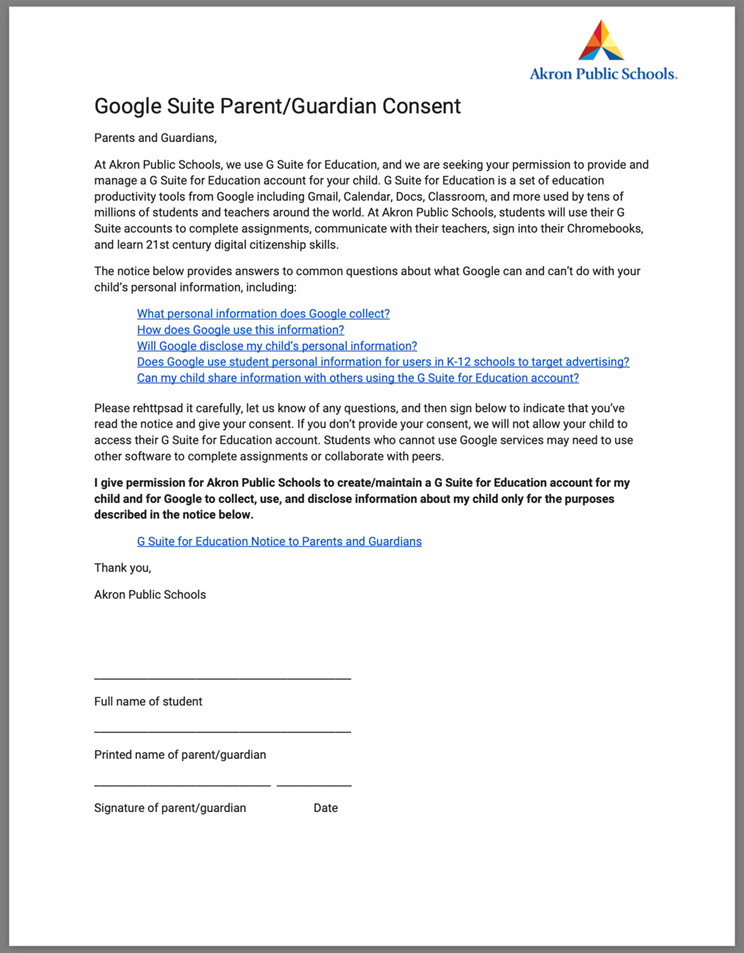

This underwhelming privacy protection for minors became a greater risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic boosted the EdTech industry as over 1.2 billion children left the classroom for remote learning.[76] Consequently, parents who may not normally interact with their child’s online activities, nor have children at schools which typically rely on EdTech tools, were given consent forms to sign. One example of the consent form that all EdTech services following COPPA rely on can be found here:

Generally, the complexities of understanding waivers and consent forms have made standardized contracts a disfavored method of contracting among many legal scholars.[78] As it pertains to the online world, the new privacy harms waived in such forms or given consent to are far more complex. Many of the possible harms are difficult to predict and may not be obvious at the time of the activity. Privacy scholars Daniel Solove and Danielle Citron note:

Privacy harms often not only involve a future risk of injury but also are compounded by an additional dimension of complexity: the range of possible future injuries is much more varied. To fully understand the implications of the collection, use, or disclosure of personal data, one must know about the future uses to which the data will be put.[79]

Moreover, privacy harms associated with data collection “are highly contextual, with the harm depending upon how the data is used, what data is involved, and how the data might be combined with other data. Sharing an innocuous piece of data with another company might provide a key link to other data or [enable] certain inferences.”[80]

Relying on parental consent under COPPA could allow minors to access additional services such as “YouTube, Google Maps, and Blogger”[81] offered by EdTech companies and within the scope of signed consent forms. This further exasperates the potential for future harms. Today, the consent apparatus is no longer asking a parent whether to allow their children to talk to strangers;[82] it is asking parents to think of the best interests of the child and consent to activities for which it is nearly impossible to grasp what the potential harmful consequences may be. How can a parent use their judgment in deciding what is in the best interests of their child and make an informed choice when it may not even be clear what consequences the use of an application might have for their beloved child?

To provide the right framework of privacy protection for minors, it is illuminating to investigate the common law of torts and the doctrine of assumption of risk. As Part II illustrates, even for physical injuries that are much clearer in nature, courts have been reluctant to allow parents to waive their child’s right to sue because many courts view such waivers to be at odds with what is in the best interests of the child.

II. Parental Waivers of Liability for Physical Injuries

A. To a Willing Person It Is Not a Wrong

The Latin maxim volenti non fit injuria (volenti) means “to a willing person it is not a wrong.”[83] Black’s Law Dictionary translates the phrase as “a person is not wronged by that to which he or she consents.”[84] And it defines it as “[t]he principle that a person who knowingly and voluntarily risks danger cannot recover for any resulting injury.”[85] The idea of volenti has been traced as far back as the times of Aristotle.[86] Volenti originated in the civil law tradition and was later incorporated into common law.[87] The maxim paved the way for our modern-day defense of assumption of risk.[88]

The Restatement (Third) of Torts has adopted the terms contractual releases and contractual waivers of liability to emphasize the contractual nature of such documents.[89] The “individualistic tendency of common law” was quick in picking up the defense.[90] Professor Francis Bohlen wrote on the popularity of the defense:

Each individual is left free to work out his own destinies; he must not be interfered with from without, but in the absence of such interference he is held competent to protect himself. While therefore protecting him from external violence, from imposition and from coercion, the common law does not assume to protect him from the effects of his own personality and from the consequences of his voluntary actions or of his careless misconduct.[91]

The Industrial Revolution also welcomed contractual limitations on liability. Companies began using contracts to restrict their liability for physical injuries.[92] These contracts were beginning to raise concerns. For some, it would have been impossible to “contract upon anything approaching a fair footing of equality.”[93] These concerns were first raised in services that were considered public goods, such as carriage of goods or carriage of passengers.[94] However, industrialization “required the recognition of affirmative duties of care, which constrained voluntary assumption of risk contracts.”[95]

In the second half of the twentieth century, as modern notions of consumer protection emerged, courts began to entertain public policy objections to certain exculpatory contracts. One of the most prominent cases that dealt with the role of public policy in judging an exculpatory clause is Tunkl v. Regents of the University of California.[96] Tunkl involved a patient, who later passed away due to injuries incurred, signing the hospital’s waiver form and later suing the hospital for negligence.[97] The court laid out a six-factor test in determining when public policy can overrule a contractual release of liability.[98] This public policy test has now been widely adopted by many other states.[99]

Nevertheless, the scope of enforceability of waivers of liability continues to cause controversy.[100] The general attitude of U.S. courts is that waivers that tend to remove liability for physical injuries caused by gross negligence may be struck down.[101] However, while disfavored, waivers of liability concerning ordinary negligence are typically upheld, with some exceptions such as appearing to be against public policy or at times unconscionable to the court.[102] Nevertheless, courts have treated parental waivers of liability for children’s injuries differently, and that is where this piece’s analysis turns.[103] The contrast with parental authority in signing consent forms for children’s digital privacy protections is illuminating.

B. Parental Waiver of Liability

Courts have not been consistent in their analysis of parental waivers concerning ordinary negligence and physical injuries for children versus those of adults. By contrast, most courts have held that waivers of potential liability for gross negligence or recklessness are unenforceable.[104] Jurisdictions such as Colorado and Alaska have addressed the issue through legislation and allow for the enforceability of parental waivers.[105] In Colorado’s case, the legislature took the initiative after the Supreme Court of Colorado invalidated a parental waiver in a case involving a minor becoming blind as a result of a ski accident.[106]

In jurisdictions where the legislature has not expressly affirmed or disaffirmed parental waivers of liability, courts’ primary reasons for upholding parental waivers can be divided into three main categories: (1) parents are acting in the best interests of their children and courts will generally defer to the authority of parents to make such decisions; (2) cities benefit from children participating in recreational activities, and as a matter of public policy, states encourage such businesses, and they should be protected from the economic burden of potential liability lawsuits; and (3) when nonprofits and schools are involved, the reasonable approach is protecting such entities that benefit the community and children; otherwise, the financial toll on them would make it impossible for nonprofits and schools to offer their services.

For example, in Sharon v. City of Newton[107] in Massachusetts, which upholds parental waivers of their children’s claims, a student whose parent had signed a waiver form was injured on the school’s premises while practicing cheerleading.[108] In upholding the parental waiver, the court discussed parental authority and cited the Supreme Court case Parham v. J.R.,[109] which involved the question of the authority of a parent to admit their minor child into a mental health facility.[110] Sharon quoted Parham, stating “[t]he law’s concept of the family rests on a presumption that parents possess what a child lacks in maturity, experience, and capacity for judgment required for making life’s difficult decisions.”[111]

The court noted that “[t]o hold that releases of the type in question here are unenforceable would expose public schools, who offer many of the extracurricular sports opportunities available to children, to financial costs and risks that will inevitably lead to the reduction of those programs.”[112]

Courts in other jurisdictions such as California,[113] Maryland,[114] and New Jersey,[115] have similar approaches in upholding parental waivers.[116] But it appears that these jurisdictions are in the minority and that most do not uphold parental waivers of children’s claims for negligence.[117] This is particularly important when seen in contrast to waivers signed by adults. As previously discussed, most states uphold adult waivers for physical injuries resulting from ordinary negligence, with exceptions for successful public policy or unconscionability defenses.[118]

In striking down parental waivers, courts consistently mention the importance of protecting the welfare of the child and “guard[ing] minors against improvident parents.”[119] One court added maintaining the peace of family unions because otherwise “[i]f a parent could enter into a binding contract of indemnification regarding tort injuries to her minor child, the result would be that the child, for full vindication of his legal rights, would need to seek a recovery from his parent.”[120] Courts have also cited to the parens patriae doctrine, by which a state may restrict parental control for a child’s wellbeing.[121]

A closer look at parental waivers illustrates that courts also differentiate between recreational activities conducted in association with schools and those not connected to schools that are for commercial purposes only.[122] For example, the state of New Jersey, which typically upholds waivers of potential claims for negligence,[123] acknowledges that “different public policies apply for non-profit waivers.”[124] One court, in striking down a parent’s waiver, noted: “Although a minority of states have upheld a parent’s pre-injury exculpatory agreement on behalf of a minor child, they have done so primarily on the basis that the defendant is a government or non-profit sponsor of the activity.”[125] This view is also supported by statutes enacted to protect nonprofit organizations and public schools.[126]

It is important to take note of the underlying reasoning offered by courts in educational settings. Generally, such waivers, unlike those in commercial settings, are considered permissible because of the benefits that participation in school-related activities and sports provide for children.[127] One may argue that the same reasoning applies to student use of EdTech and the experiences they offer students. However, this analogy is flawed. These technologies are all on a spectrum with a mix of good and bad elements, like access to chatrooms, an additional service offered to students—and so they may not necessarily fall along the same lines and may be less positive.[128]

Moreover, the concern that schools may suffer undue financial burdens from potential lawsuits by minors does not exist in the EdTech setting. In the context of EdTech, the potential lawsuit would involve suing a commercial entity, a company that works for profit, puts its interest above all others, and competes to win access to schools in the first place. In many cases, companies like Google are also creating their EdTech products only as part of a much larger enterprise.[129] As such, it is important to distinguish EdTech from the typical school setting by understanding the transactional and commercial nature of contracts between an EdTech company and the school.[130]

Indeed, companies compete to gain access to schools for both the short-term and, more importantly, long-term benefits that such participation offers them. Even when it appears to be a philanthropic action, technology companies at schools are “influencing the subjects that schools teach, the classroom tools that teachers choose and fundamental approaches to learning.”[131] That is why the same line of public policy reasoning in protecting the school as an entity necessary for the best interests of the child no longer exists in connection with EdTech. There is no public policy that necessitates the promotion of commercial activity at the expense of children’s privacy.

The foregoing analysis has shown that allowing EdTech companies to access and profit from children’s data by a simple consent form signed by a parent is at odds with the common law tradition which invalidates parental waivers signed on behalf of minors. Part III provides an analysis of how these findings can play a role in protecting minors’ privacy and deciding how to treat parental consent forms.

III. EdTech and Minor’s Privacy Protection: A Way Forward

A. The Problem with Verifiable Parental Consent

COPPA lays out detailed instructions for mandatory notices and acquiring a verifiable parental consent. It mandates companies seek the required verifiable consent before “collection, use, and/or disclosure of personal information from and about children on the internet,”[132] and do so by, among other things, “provid[ing] notice on the Web site or online service of what information it collects from children, how it uses such information, and its disclosure practices for such information.”[133] It further states that this notice of information practices “must be clearly and understandably written, complete, and must contain no unrelated, confusing, or contradictory materials.”[134]

While COPPA might thus seem to be protective of privacy, scholars have questioned whether privacy notices of the sort on which it relies are actually protective. As the American Law Institute’s Data Privacy project observes, “[t]he overwhelming majority of commentary, scholarship, and empirical evidence suggests that traditional notice does not work.”[135] They are often “written with an eye to avoiding legal liability.”[136] As such, COPPA’s effort in using mandatory notice as a tool for children’s privacy protection is not convincing. The ALI notes:

As privacy notices are made easier to understand, they are often made less informative. An organization’s various policies and practices regarding the protection of personal data can only be expressed in simple language to a certain point. Beyond that, a short and simplistic privacy notice will fail to convey meaningful information.[137]

Moreover, these guidelines on procedural aspects of consent forms typically show up in courts’ decisions when dealing with the validity of an adult waiver of liability. However, as this work’s previous discussion illustrated,[138] when a parental consent form is involved, courts are not so interested in how conspicuous or clear the waiver was—rather, the principal question is whether a parent waiving such a right is acting in the best interests of the child. COPPA’s framework fails to capture that main problem with such consent and instead relies on the company to “[e]stablish and maintain reasonable procedures to protect the confidentiality, security, and integrity of personal information collected from children.”[139] Companies have repeatedly failed to prioritize confidentiality and security over their own interests.[140]

An example based on Google’s forms will help illustrate these points. Google has drafted a question-and-answer document that is meant to address the concerns of parents signing their consent forms. It poses the question: Will Google disclose my child’s personal information? The document then answers that:

Google will not share personal information with companies, organizations and individuals outside of Google unless one of the following circumstances applies: With parental or guardian consent. Google will share personal information with companies, organizations or individuals outside of Google when it has parents’ consent (for users below the age of consent), which may be obtained through G Suite for Education schools.[141]

It does not say how that consent is obtained neither defines the scope of the consent. The fact that Google can share a minor’s personal information with companies outside of Google with parents’ consent is a clear indication why it does not matter how simplified the consent form may be. Under this policy, Google will be allowed to share minors’ personal information beyond what is necessary for the operation of the core of its educational services offered at schools. In other words, once Google, or any other EdTech company, has the precious “verifiable parental consent,” it has a wide range of ways in which it can use and benefit from the data.

The heightened concern here is that the use of the application for a minor is not a matter of recreational activity such as with online games. EdTech is all about a minor’s education. As discussed in the Introduction, using technology for learning purposes and remote education is no longer a luxury. After the pandemic, “at least several hundred of the nation’s 13,000 school districts have established virtual schools this academic year, with an eye to operating them for years to come.”[142] With the rise of EdTech, schools have become consumers.[143] As one scholar notes: “[e]ducation technology not only can shift power, it can reframe education policy debates in subtle ways.”[144] Hence, children’s use of EdTech is a matter of necessity. And for issues of necessity, there is a consensus amongst various courts that even adult waivers of liability are invalid as violating public policy, let alone parental waivers.[145]

In addition, it is a heavy burden, even for those working in civic organization and nonprofits who study and monitor privacy compliance by EdTech, to access and understand school contracts and EdTech practices that may be undermining students’ privacy. For example, in 2015 the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) conducted a study in Massachusetts in which they accessed schools’ records through public record laws and compared their findings with the information that would be available to a parent online regarding children’s privacy.[146] They observed the financial cost associated with accessing such records and noted:

Newton [Public School District] demanded $5,834 to produce all but a few records; Lexington asked for approximately $2,200; and Waltham estimated the cost would be between $1,020 and $1,360, plus the cost of making copies. While we were interested to learn how these districts handle student privacy, we did not have the resources to meet these demands.[147]

This example in Massachusetts illustrates how difficult it is in practice to learn and access the content of EdTech contracts and their practices.[148]

COPPA’s emphasis on obtaining verifiable parental consent appears to only resolve the ongoing debate about data breach and data use by tech companies where an adult user can hardly be deemed to have consented to such use of their personal data. This is in part due to a lack of general data privacy protection in the United States. Today, U.S. law is also not “clear on when a consumer has effectively consented to an otherwise impermissible use of her information.”[149] Therefore, COPPA’s protection of relying on the ill-suited mechanism of parental consent does not effectively resolve the issue of the risks and potential harms associated with the collection of data from minors.

An additional important note here is the issue of public policy. As Part II’s discussion of parental waivers of liability for physical injuries illustrated, in such cases, courts are not as much concerned with the procedure of how the consent form was signed,[150] as they are with whether signing such waivers is in the best interests of the child, whether striking down such waivers discourages recreational activities, and how and when to protect involved nonprofit organizations.

This piece addressed these concerns in Part II by emphasizing that most jurisdictions do not uphold parental waivers for children’s personal injury. It noted that when courts uphold such waivers dealing with nonprofits and schools, they have a different set of concerns in mind (such as protecting these nonprofit institutions in the community). But those concerns do not apply in the present context, as the nature of the transaction between EdTech companies and the school is a commercial one and any liability should be placed on the company, not the school.[151]

Another point to highlight is the issue of necessary services and the role of the public policy defense.[152] Historically, courts have been reluctant to uphold waivers for services that share a public calling, such as communication tools (telegraph transmission companies), carriage of passengers and goods, innkeeping, and hospital care.[153] The Restatement (Second) of Torts notes:

Where the defendant is a common carrier, an innkeeper, a public warehouseman, a public utility, or is otherwise charged with a duty of public service, and the agreement to assume the risk relates to the defendant’s performance of any part of that duty, it is well settled that it will not be given effect. Having undertaken the duty to the public, which includes the obligation of reasonable care, such defendants are not free to rid themselves of their public obligation by contract, or by any other agreement.[154]

This is an important point as it relates to this piece’s positions on EdTech. Education, too, is a public calling. While waivers of liability for physical injury are upheld in courts to protect schools as crucial community institutions, EdTech companies do not need the same protection. Since the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated the presence of EdTech providers, they have become more like hospitals—while communities need their services and thus need the private sector to invest, they cannot be allowed to insulate themselves by waivers of liability that take away parents’ right to sue.[155]

In response, the EdTech industry may argue that parents do in fact have the option of not signing the consent form or of enforcing their rights in the future to review the data collected and refuse future use of such data.[156] However, given the reality of the education space, singling out their child as the only one not having their parents’ permission to use the new EdTech tools in the classroom is not what any parent would want.[157] There is a “network effects” problem—parents have no meaningful option to withhold consent if access to the tech is for all practical purposes necessary for the child to participate in ordinary school activities. In such a situation, there is no meaningful choice.

Since the pandemic, it has also become functionally impossible not to sign such forms, since not consenting could at times mean no access to education. Therefore, instead of regulating the procedural aspect of the consent form, the legislature must address the substantive aspects of how to contain the reach of EdTech companies and limit their use of minors’ data.

Those who favor the current consent-form approach of COPPA, and who may view the Act as paternalistic even in its current format,[158] may also argue that the Supreme Court’s understanding of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause has been to afford parents the “fundamental right . . . to make decisions concerning the care, custody, and control of their children.”[159] This right extends to education, as the U.S. Supreme Court has held “it is the natural duty of the parent to give his children education.”[160] Therefore, parents should have the right to allow their minors to use EdTech tools that may even undermine their privacy and potentially cause future dignitary harms.

But this reasoning is not warranted here. The consent form at issue here and the concern of breach of privacy this piece is advocating against do not bring in the question of a parent’s right to shape their child’s education. Rather, this piece voices the concern that the child’s use of technology in school under the parental-consent apparatus puts the child’s privacy rights at the mercy of a tech company. In the same way that parental waivers for physical injury have been barred by courts without violating a parent’s right, here too Congress or state legislatures are in positions to intervene.

Moreover, the constitutional rights in question are rights designed to ensure that the government does not interfere unduly with parental choices about how to raise one’s children. It is not concerned with the rights that parents or children have in relation to those whose services they purchase. A court’s denial to a parent of the effective ability to sign a waiver on behalf of the child does not meaningfully interfere with any parental right to shape the child’s education. It is just that the parent cannot decide to waive the child’s right to sue.

Indeed, one may argue that COPPA has already taken steps to regulate the content of the contract a parent may sign in reliance on the parens patriae doctrine. The protection offered is not enough and Congress should go one step further by, for example, regulating EdTech companies directly rather than exonerating itself from its duty to protect minors by requiring a consent form.

Moreover, as previously explained,[161] with the ambiguity of the risks and harms associated with EdTech companies’ collection of minors’ data, the parent is also not in reality able to make an informed choice. Common Sense Media, a U.S.-based nonprofit organization that has been studying children’s privacy for several years,[162] issued its latest report for 2021. One of its key findings was that despite the progress made in the past years for more transparency in privacy policies, making an informed choice continues to be a major concern for consumers and parents.[163]

Additionally, choosing the EdTech company involved with the school is typically not a choice that the parent makes. Rather, the parent is given the consent form based on the school’s selection and choice of the EdTech company. Even though we can imagine scenarios in which a parent chooses a school specifically for the technology services it offers students, that is not the case for most people who must enroll their children in public schools and are given such forms on a take-it-or-leave-it basis.

It is important to also note that parents might be more likely to sign any EdTech school waiver since they are already trusting the school with their child’s physical presence every day. If they are trusting an institution with their child, why would they hesitate to trust them with their child’s data? This is another reason why intervention and oversight rather than relying on parental consent is necessary.

Similar concerns have been raised in a dissenting opinion in a dispute about the validity of a parental waiver for a public school’s YMCA summer program that resulted in a near-drowning accident. In Hillerson v. Bismarck Public Schools[164] the trial court issued summary judgment upholding the waiver, but the Supreme Court of North Dakota reversed based on ambiguity concerning the waiver that raised an issue concerning the intent of the signing party.[165] The dissent wrote in favor of invalidating the waiver based on public policy even though it concerned a public school’s summer program.[166]

The dissent argued that the summer program was an essential service subject to public regulation, and presenting a waiver of a child’s rights to their parents under the circumstances of this case was against public policy and “contrary to good morals.”[167] There was disparate bargaining power between the parents and the organizations running the summer program; there was no negotiation, the children were admitted to the program on full scholarship, and the family had no choice but to sign the waiver or go without summer childcare due to their income.[168]

Moreover, COPPA currently does not even give the parents a private right of action. The FTC’s implementing regulations state: “the FTC has authority to enforce violations of such rules by seeking penalties or equitable relief. COPPA also authorizes state attorneys general to enforce violations affecting residents of their states.”[169] Therefore, by neither expressly granting parents a private right of action nor conveying any criminal liability, COPPA seems to be carving out apparent control for parents over their child’s data without actually offering the protection a minor deserves in using essential EdTech services.

New legislative initiatives should consider regulation that would move away from the centrality of ineffective parental consent. There may be concerns that with such protective regulations EdTech companies will lose incentive to provide such services just as they are becoming necessary for children’s education. This objection is without merit. EdTech companies are motivated by profit from their sales to schools and, more importantly, incentivized by building a generation accustomed to specific products that are likely to be used by students even beyond their school years. With tough regulation, companies will be competing for a spot at schools by promoting their top-notch privacy-protection tools rather than distracting apps and colorful games.

B. Preemption and Privacy Torts

Until new legislative initiatives take place, parents may wonder how to react to alleged violations of minors’ privacy. While COPPA has not created a private right of action, common law privacy torts appear to continue to remain an option outside of COPPA. In recent years, lawsuits relying on common law privacy torts have been filed against companies for their data collection practices and breaches of privacy.[170] While scholars have proposed new torts for digital privacy harms,[171] the four traditional common law privacy torts relied on today were first categorized by Dean Prosser as:

1. Intrusion upon the plaintiff’s seclusion or solitude, or into his private affairs.

2. Public disclosure of embarrassing private facts about the plaintiff.

3. Publicity which places the plaintiff in a false light in the public eye.

4. Appropriation, for the defendant’s advantage, of the plaintiff’s name or likeness.[172]

Understanding and using common law privacy torts are even more important after the U.S. Supreme Court decision in TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez.[173] In TransUnion, the Court concluded that, to have Article III standing (concrete injury-in-fact) for data privacy claims, plaintiffs must show a common law analogous harm.[174] The case created a new challenge to showing injury-in-fact to sue for data and privacy rights violation.[175] Despite the unpopularity of the decision amongst some privacy scholars,[176] the approach in this piece is well in line with the Supreme Court’s decision noting that plaintiffs must identify a close historical or common law analogue for their asserted privacy injury.[177] A set of common law analogues for privacy harms is found in privacy torts.

The most common tort that is used in digital-privacy-related lawsuits appears to be the tort of intrusion upon seclusion.[178] Regarding this tort, the Restatement (Second) of Torts states, “One who intentionally intrudes, physically or otherwise, upon the solitude or seclusion of another or his private affairs or concerns, is subject to liability to the other for invasion of his privacy, if the intrusion would be highly offensive to a reasonable person.”[179] Under this tort, a showing of reasonable expectation of privacy and highly offensive behavior, albeit a data practice, may be sufficient to argue that data collection and their procedures involving surveillance satisfy the requirements for this civil wrong.[180]

A challenge with using this tort is the defense of consent.[181] If a user is deemed to have consented to surveillance and the use of their data, the user can no longer move forward with this tort. That is where the question of effective consent comes into play for both adults and minors. If a parent’s consent form is ruled as against public policy in an EdTech-related case, as this piece argues it should be, then a minor’s action for damages, whether brought by a guardian or by the minor after reaching the age of competency, may move forward.[182]

But has COPPA ruled out lawsuits for state common law privacy? The law states: “No State or local government may impose any liability for commercial activities or actions by operators in interstate or foreign commerce in connection with an activity or action described in this chapter that is inconsistent with the treatment of those activities or actions under this section.”[183] However, courts have not been consistent in barring privacy claims.

In In re Nickelodeon Consumer Privacy Litigation,[184] minors under the age of thirteen brought a class action against Viacom, the company that owns the children’s television station Nickelodeon and operates Nick.com,[185] and Google, alleging that they had “unlawfully used cookies to track children’s web browsing and video-watching habits on Viacom’s websites.”[186] They brought their action based on several legal grounds, including the common law privacy tort of intrusion upon seclusion.[187] Plaintiffs alleged that Google and Viacom had collected various minors’ personally identifiable information in order to sell targeted advertisements.[188] The Third Circuit affirmed the district court’s dismissal of all claims except the plaintiffs’ claim against Viacom for intrusion upon seclusion and remanded the intrusion claim for further proceedings.[189]

In reaching this decision, the Third Circuit first stated that the general presumption is against preemption.[190] It noted that “when federal laws have preemptive effect in some contexts, states generally retain their right ‘to provide a traditional damages remedy for violations of common-law duties when those duties parallel federal requirements.’”[191] Since COPPA was silent on this issue, despite authorizing the FTC and attorneys general on matters of enforcement, the presumption should be against preemption.

The court further reasoned that the intrusion upon seclusion claim in this case was not inconsistent with COPPA. It stated:

In our view, the wrong at the heart of the plaintiffs’ intrusion claim is not that Viacom and Google collected children’s personal information, or even that they disclosed it. Rather, it is that Viacom created an expectation of privacy on its websites and then obtained the plaintiffs’ personal information under false pretenses. Understood this way, there is no conflict between the plaintiffs’ intrusion claim and COPPA. While COPPA certainly regulates whether personal information can be collected from children in the first instance, it says nothing about whether such information can be collected using deceitful tactics. Applying the presumption against preemption, we conclude that COPPA leaves the states free to police this kind of deceptive conduct.[192]

Although the parties reached a $1.1 million settlement,[193] this important 2016 decision shows a way forward for common law privacy tort claims despite COPPA.

The scope and reach of In re Nickelodeon are, however, open to interpretation. In a different case, a federal district court in California ruled in 2021 that COPPA preempts common law causes of action. In Hubbard v. Google LLC,[194]minor plaintiffs brought a class action by and through their guardian ad litem against Google and YouTube (collectively, Google) alleging that Google had “unlawfully violated the right to privacy and reasonable expectation of privacy of their children, who are all under thirteen years of age.”[195] Plaintiffs alleged that Google “did its tracking, profiling, and targeting of children while feigning compliance with applicable federal and state laws.”[196] They further alleged that Google “tracked and collected the personal information of children under the allegedly false pretense that Google would be ‘transparent’ with parents about what information was being collected from child viewers and compliant with applicable legal requirements and prohibitions, including COPPA.”[197]

The allegations included a wide range of causes of actions, including state privacy laws, consumer protections laws, unjust enrichment, and the tort of intrusion upon seclusion.[198] Defendant, on the other hand, brought a motion to dismiss “on several grounds, with preemption as a threshold issue.”[199] The court sided with Google. The court noted that, based on a prior decision, since Congress did not expressly create a private right of action in COPPA, “the plain text of the statute clearly indicates Congress’s desire to expressly preempt Plaintiffs’ state law claims.”[200] Because all the plaintiffs were under the age of thirteen, the alleged conduct is covered and preempted by COPPA.[201]

But plaintiffs argued that the court should follow In re Nickelodeon Consumer Privacy Litigation and rule that plaintiffs had sufficiently alleged deceptive conduct that goes beyond what is covered by COPPA.[202] The court disagreed, ruling that “Plaintiffs have not adequately alleged deceptive conduct that places Defendants’ behavior outside of what is regulated by COPPA.”[203] Plaintiffs appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.[204] In December 28, 2022, the Ninth Circuit panel issued its opinion reversing the district court’s dismissal on preemption grounds.[205] The court held that “it would be nonsensical to assume Congress intended to simultaneously preclude all state remedies for violations of those laws. If exercising state-law remedies does not stand as an obstacle to COPPA in purpose or effect, then those remedies are treatments consistent with COPPA.”[206] This holding opens the possibility of lawsuit by minors based on state-law remedies, including common law of torts, despite the COPPA regime.

Moreover, a group of minors continues to remain unprotected as COPPA only applies to minors below the age of thirteen. As previously noted, the age limit is inconsistent with the common law protection that declares contracts of minors below the age of eighteen voidable, and in certain circumstances, void.[207] Nevertheless, although not required by COPPA, companies may ask for parental waivers to insulate themselves from potential liability for kids between the ages of thirteen to eighteen.[208] In such cases, given this piece’s analysis of waivers of liability, courts should view EdTech as a commercial player engaged in a commercial activity and invalidate the consent and waiver forms.[209] Therefore, where common law privacy harms such as intrusion upon seclusion or appropriation of likeness can be associated with certain activities of an EdTech company or, more broadly, a company that is active in the children’s digital-economy landscape, parental waivers of liability for privacy harms should be invalidated as working against the best interests of the child.

Conclusion

Interaction with the EdTech industry has increasingly become part of parents’ and students’ lives. However, the current legal protections fall short in protecting minors’ digital privacy. COPPA relies on parental consent for the protection of minors’ digital privacy. This piece argued that relying on parental consent forms to protect children’s digital privacy is inadequate and ill-suited. By comparing the privacy-protection apparatus to parental waivers for minors’ physical injuries in torts, this work illustrated that waivers are disliked by courts—and in physical settings, most jurisdictions do not uphold parental waivers. In most cases when courts do uphold waivers, such waivers are associated with schools and nonprofit activities that are understood as noncommercial activities. Nevertheless, the EdTech industry is a for-profit industry, albeit one operating at schools, and the contracts between the school and the EdTech companies are of a commercial nature. With the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, the EdTech industry has further become a necessary medium for acquiring education for many children, which underscores the public policy defense that necessitates stepping away from insufficient parental consent forms.

This important and one-of-a-kind common law analysis reinforced the need to move away from frameworks that seek to protect children’s digital privacy by relying on notice and parental consent forms and instead advocated for the adoption of positive law to protect children’s digital privacy. Finally, this piece also illuminated a narrow way to bring lawsuits for digital privacy harms based on common law privacy torts.

- . Complaint, New Mexico ex rel. Balderas v. Google, LLC, 489 F. Supp. 3d 1254 (D.N.M. 2020) (No. 1:20-cv-00143-NF). ↑

- . 489 F. Supp. 3d 1254 (D.N.M. 2020), appeal dismissed, No. 20-2172, 2021 WL 8650746 (10th Cir. Dec. 17, 2021). ↑

- . 15 U.S.C. § 6502. ↑

- . N.M. Stat. Ann. §§ 57-12-1 to 57-12-26 (West 2022). ↑

- . For an analysis of this case, see Zahra Takhshid, New Mexico v. Google LLC: Children’s Privacy in the Age of e-Learning, JOLT Digest (Mar. 16, 2020), https://jolt.law.harvard.edu/digest/new-mexico-v-google-llc-childrens-privacy-in-the-age-of-e-learning [https://perma.cc/3XTV-FJPM]. ↑

- . Balderas, 489 F. Supp. 3d at 1258–59; Brief for Appellant at 23, Balderas, No. 20-2172 (10th Cir. Dec. 17, 2021). COPPA defines “personal information” (commonly referred to as Personally Identifiable Information or PII) as individually identifiable information about an individual collected online, including:(1) A first and last name;(2) A home or other physical address including street name and name of a city or town;

(3) Online contact information as defined in this section;

(4) A screen or user name where it functions in the same manner as online contact information, as defined in this section;

(5) A telephone number;

(6) A Social Security number;

(7) A persistent identifier that can be used to recognize a user over time and across different Web sites or online services. Such persistent identifier includes, but is not limited to, a customer number held in a cookie, an Internet Protocol (IP) address, a processor or device serial number, or unique device identifier;

(8) A photograph, video, or audio file where such file contains a child’s image or voice;

(9) Geolocation information sufficient to identify street name and name of a city or town; or

(10) Information concerning the child or the parents of that child that the operator collects online from the child and combines with an identifier described in this definition.

16 C.F.R. § 312.2 (2022). ↑

- . Balderas, 489 F. Supp. 3d at 1255. ↑

- . Id. at 1255–56. ↑

- . Id. at 1264. ↑

- . Id. at 1258–59 (first quoting Complaint, supra note 1, at 18; and then quoting 16 C.F.R. § 312.2). ↑

- . Id. at 1259 (quoting Complying with COPPA: Frequently Asked Questions, Fed. Trade Comm’n (Mar. 2015), https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/complying-coppa-frequently-asked-questions [https://perma.cc/BBL3-S5HH]; see also 16 C.F.R. § 312.5(b) (2022) (“Any method to obtain verifiable parental consent must be reasonably calculated, in light of available technology, to ensure that the person providing consent is the child’s parent.”). ↑

- . Balderas, 489 F. Supp. 3d at 1260. ↑

- . Google Workspace for Education Core and Additional Services, Google, https://

support.google.com/a/answer/6356441?hl=en [https://perma.cc/3G6N-955L]. ↑ - . New Mexico ex rel. Balderas v. Google, LLC, No. 20-2172, 2021 WL 8650746, at *1 (10th Cir. Dec. 17, 2021). ↑

- . See Barbara B. Lockee, Comment, Online Education in the Post-COVID Era, 4 Nature Elecs. 5, 5 (2021) (discussing how the pandemic forced a shift to virtual learning). ↑

- . Cathy Li & Farah Lalani, The COVID-19 Pandemic Has Changed Education Forever. This Is How, World Econ. F. (Apr. 29, 2020), https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-education-global-covid19-online-digital-learning/ [https://perma.cc/9GVA-NGQS]. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Enkelejda Kasneci, Kathrin Sessler, Stefan Küchemann, Maria Bannert, Daryna Dementieva, Frank Fischer, Urs Gasser, Georg Groh, Stephan Günnemann, Eyke Hüllermeier, Stephan Krusche, Gitta Kutyniok, Tilman Michaeli, Claudia Nerdel, Jürgen Pfeffer, Oleksandra Poquet, Michael Sailer, Albrecht Schmidt, Tina Seidel, Matthias Stadler, Jochen Weller, Jochen Kuhn, Gjergji Kasneci, ChatGPT for Good? On Opportunities and Challenges of Large Language Models for Education, EdArXiv Preprints (Feb. 1, 2023), https://edarxiv.org/5er8f/ [https://perma.cc/N7VE-4VSS] (presenting the potential benefits and challenges of educational applications of large language models like ChatGPT—an emerging AI powered chatbot that OpenAI introduced in 2022). ↑

- . Shancang Li, Li Da Xu, Shanshan Zhao, The Internet of Things: A Survey, 17 Inf Syst Front 243, 243 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-014-9492-7 [https://perma.cc/D9KW-9YPF] (“[T]he Internet of things (IoT) is a things-connected network, where things are wirelessly connected via smart sensors.”). ↑

- . See, e.g., Anita L. Allen, Minor Distractions: Children, Privacy and E-Commerce, 38 Hous. L. Rev. 751, 752–53 (2001) (discussing COPPA and the implications for parental autonomy and privacy law); Amy Rhoades, Big Tech Makes Big Data Out of Your Child: The FERPA Loophole EdTech Exploits to Monetize Student Data, 9 Am. U. Bus. L. Rev. 445, 447–48 (2020) (arguing that EdTech avoids COPPA liability and violates students’ privacy by mining data online); Kate Hamming, A Dangerous Inheritance: A Child’s Digital Identity, 43 Seattle U. L. Rev. 1033, 1048 (2020) (considering COPPA and the lack of federal laws to protect children’s personal information privacy or provide children with remedies against their parents); Lauren A. Matecki, Update: COPPA Is Ineffective Legislation! Next Steps for Protecting Youth Privacy Rights in the Social Networking Era, 5 Nw. J. L. & Soc. Pol’y 369, 370 (2010) (highlighting the shortcomings of COPPA in protecting children thirteen and over and noting the challenges with the rise of social networking). ↑

- . In May 2022, the FTC announced its plan “to crack down” on educational technology companies that “illegally surveil” children learning online. Press Release, Fed. Trade Comm’n, FTC to Crack Down on Companies that Illegally Surveil Children Learning Online (May 19, 2022), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2022/05/ftc-crack-down-companies-illegally-surveil-children-learning-online [https://perma.cc/5JFS-8J4J]. ↑

- . Allen, supra note 20, at 754. ↑

- . See id. at 755 (discussing “the drive to protect children from threats to their safety and moral development”). ↑

- . Overview of the Privacy Act: 2020 Edition, U.S. Dep’t of Just., https://www.justice.gov/opcl/overview-privacy-act-1974-2020-edition/introduction [https://perma.cc/N7K7-DHXL] (Oct. 4, 2022). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974, Pub. L. No. 93-380, tit. V, § 513, 88 Stat. 571 (codified as amended at 20 U.S.C. § 1232g). ↑

- . See 20 U.S.C. § 1232g(b), (d) (prohibiting the funding of any program or educational agency or institution that engages in the practice of releasing educational records of students without the consent of their parents, and listing exceptions, and transferring the power to consent to the student at age eighteen). ↑

- . Id.; Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), U.S. Dep’t of Educ., https://www2.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/fpco/ferpa/index.html [https://perma.cc/A33L-RL76] (Aug. 25, 2021). Given new technologies, parental permission for the release of children’s records can also include the disclosure of “images of students’ faces or live footage of them to a company deploying a facial recognition system for the school.” Lindsey Barrett, Ban Facial Recognition Technologies for Children—and for Everyone Else, 26 B.U. J. Sci. & Tech. L. 223, 273 (2020) (first citing 20 U.S.C. § 1232(g); and then citing 34 C.F.R. § 99.3 (2019)). “Biometric record, as used in the definition of personally identifiable information, means a record of one or more measurable biological or behavioral characteristics that can be used for automated recognition of an individual. Examples include fingerprints; retina and iris patterns; voiceprints; DNA sequence; facial characteristics; and handwriting.” 34 C.F.R. § 99.3 (2019). ↑

- . Pam Dixon, A Brief Introduction to Fair Information Practices, World Priv. F. (June 5, 2006), https://www.worldprivacyforum.org/2008/01/report-a-brief-introduction-to-fair-information-practices/ [https://perma.cc/2V58-3A4T]. In 1980, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) also issued its privacy guidelines that influenced many countries in adopting similar principles (later updated in 2013). OECD Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/sti/ieconomy/oecdguidelinesontheprotectionofprivacyandtransborderflowsofpersonaldata.htm [https://perma.cc/VCG2-X2NK] (2013). ↑

- . Fed. Trade Comm’n, Privacy Online: A Report to Congress 7 (1998) [hereinafter Privacy Online], https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/privacy-online-report-congress/priv-23a.pdf [https://perma.cc/9KFF-SF6F]. ↑

- . Allen, supra note 20, at 752. ↑

- . 15 U.S.C. § 6502(b)(1). ↑

- . Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule, 16 C.F.R. pt. 312 (2000). The uses of the term COPPA throughout the piece refer to both the statute and the regulation. ↑

- . Allen, supra note 20, at 753 (footnote omitted). ↑

- . Id. at 771. ↑

- . Joseph M. Perillo, Contracts 259 (7th ed. 2014). Generally, minors are referred to as “infants” in the legal literature. Ian Ayres & Gregory Klass, Studies in Contract Law 468 (9th ed. 2017); Perillo, supra, at 259–60. ↑

- . Perillo, supra note 38, at 259–60; see Casey v. Kastel, 142 N.E. 671, 673 (N.Y. 1924) (finding contract with a minor voidable, not void). For example, a minor is liable in quasi-contracts for necessities like a basic public school education. See Perillo, supra note 38, at 271–72. ↑

- . Perillo, supra note 38, at 260. ↑

- . Id. (citing A.V. ex rel. Vanderhye v. iParadigms, LLC, 562 F.3d 630 (4th Cir. 2009)). ↑

- . 15 U.S.C. § 6501(1); see also 16 C.F.R. § 312.2 (2022) (same). ↑

- . Complying with COPPA: Frequently Asked Questions, Fed. Trade Comm’n (July 2020), https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/complying-coppa-frequently-asked-questions [https://perma.cc/M672-RY3K]). ↑

- . Online Privacy and Security, Fed. Trade Comm’n, https://consumer.ftc.gov/identity-theft-and-online-security/online-privacy-and-security [https://perma.cc/4WAN-PE27]. ↑

- . 16 C.F.R. § 312.3(a)–(e) (2022). ↑

- . See Allen, supra note 20, at 758 (“COPPA was enacted to curb the informational privacy loss that threatens families with young children.”). ↑

- . Id. (noting that COPPA was passed in light of studies citing risks to children, like “informational privacy losses, . . . exploitation by advertisers, accessibility to child sexual predators, and exposure to adult content . . . . The [legislative intent] was to make it more difficult for Web sites to collect personal information . . . without a parent’s knowledge and consent”). ↑

- . Privacy Online, supra note 32, at 5. ↑

- . From the Garage to the Googleplex, Google, https://about.google/our-story/ [https://perma.cc/938D-5NZ6]. ↑

- . See generally Barrett, supra note 30 (discussing threats and harms to children from facial recognition technology). ↑

- . See Thorin Klosowski, Facial Recognition Is Everywhere. Here’s What We Can Do About It., N.Y. Times: Wirecutter (July 15, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/wirecutter/blog/how-facial-recognition-works/ [https://perma.cc/FF77-T4NX] (stating facial recognition’s first dramatic shift to the public stage came in 2001, when law enforcement used facial recognition technology on crowds at Super Bowl XXXV). ↑

- . Press Release, Fed. Trade Comm’n, FTC Strengthens Kids’ Privacy, Gives Parents Greater Control Over Their Information By Amending Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule (Dec. 19, 2012), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2012/12/ftc-strengthens-kids-privacy-gives-parents-greater-control-over [https://perma.cc/9KHY-AKG6]. ↑

- . Press Release, Fed. Trade Comm’n, Revised Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule Goes Into Effect Today (July 1, 2013), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2013/07/revised-childrens-online-privacy-protection-rule-goes-effect [https://perma.cc/Q63A-XURT]. ↑

- . Kristin Cohen & Peder Magee, FTC Updates COPPA Compliance Plan for Business, Fed. Trade Comm’n (June 21, 2017), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/blogs/business-blog/2017/06/ftc-updates-coppa-compliance-plan-business [https://perma.cc/KU2C-ZFHQ]. ↑

- . S. 1628, 117th Cong. § 1 (2021). ↑

- . Id. § 3(a)(19); see, e.g., id. § 3(b)(1) (amending a heading to include minors in addition to children). ↑

- . Id. § 3(a)(4), (b)(3). ↑

- . The bill was also once introduced in 2018. Hamming, supra note 20, at 1048. ↑

- . S. 1423, 117th Cong. (2021). ↑

- . S. 3411, 116th Cong. (2020). ↑

- . Id. § 2. ↑

- . Press Release, Ed Markey, U.S. Senator, Senators Markey and Blumenthal, Rep. Castor Reintroduce Legislation to Protect Children and Teens from Online Manipulation and Harm (Sept. 30, 2021), https://www.markey.senate.gov/news/press-releases/senators-markey-and-blumenthal-rep-castor-reintroduce-legislation-to-protect-children-and-teens-from-online-manipulation-and-harm [https://perma.cc/Z8JC-DBA3]. ↑

- . Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code §§ 22580–22582 (West 2022); Thomas R. Burke, Deborah A. Adler, Ambika K. Doran & Tom Wyrwich, California’s “Online Eraser” Law for Minors to Take Effect Jan. 1, 2015, Davis Wright Tremaine LLP (Nov. 17, 2014), https://www.dwt.com/insights/2014/11/californias-online-eraser-law-for-minors-to-take-e [https://perma.cc/J2RL-FV5S]. ↑

- . Teens’ Online Privacy, Consumer Fed’n of Calif., https://consumercal.org/about-cfc/cfc-education-foundation/what-should-i-know-about-privacy-policies-2/teen-online-privacy/ [https://perma.cc/3NQV-PCYT]. In October 2021, Google announced that it is possible for children below the age of eighteen or their parents to ask Google to remove their images, with exceptions for newsworthiness and public interest. See Remove Images of Minors from Google Search Results, Google, https://support.google.com/websearch/answer/10949130?hl=en [https://perma.cc/GJT9-TU4V]; see also James Vincent, You Can Now Ask Google to Remove Images of Under-18s from Its Search Results, The Verge (Oct. 27, 2021, 3:56 AM), https://www.theverge.com/2021/10/27/22748240/remove-images-google-search-results-under-18-request-how-to [https://perma.cc/A5EV-893Y]. ↑

- . Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 22580(d) (West 2022). ↑

- . Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.99.30(b)(1) (West 2023). The law takes effect July 1, 2024.

2022 Cal. Legis. Serv. Ch. 320 (A.B. 2273) (West). ↑ - . 15 U.S.C. § 6502(d). ↑

- . K-12 School Service Provider Pledge to Safeguard Student Privacy, Student Priv. Pledge, https://studentprivacypledge.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Student-Privacy-Pledge-2-Pager.pdf [https://perma.cc/A5ZV-CK2X] [hereinafter The Pledge]; see also Student Priv. Pledge, https://studentprivacypledge.org [https://perma.cc/8DHF-Y37G] (counting 258 total 2020 Pledge signatories as of February 2023). ↑

- . The Pledge, supra note 68. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . The Pledge has other shortcomings too. For example, it carves out an exception for nonidentifiable student information without explaining the procedure of identification. See id. (defining “student personal information” as “personally identifiable information as well as other information when it is both collected and maintained on an individual level and is linked to personally identifiable information” (emphasis added)). The Electronic Frontier Foundation reports on this issue that “[w]hile the U.S. Department of Education has drafted guidance on data de-identification, the 2020 Pledge fails to define that term and thus fails to provide a standard for de-identification that provides some baseline privacy protection and that can be used to determine signatories’ compliance with the Pledge.” Sophia Cope, Jason Kelley & Bill Budington, FPF’s 2020 Student Privacy Pledge: New Pledge, Similar Problems, Elec. Frontier Found. (Sept. 28, 2021), https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/09/fpfs-2020-student-privacy-pledge-new-pledge-similar-problems [https://perma.cc/ZR3F-45VF]. This is important as “[n]ot all de-identification processes provide adequate protection. For example, an edtech provider might build a student profile that contains sensitive student data and then simply replace that student’s name with an ID number.” Id. ↑

- . See, e.g., Stacey B. Steinberg, Sharenting: Children’s Privacy in the Age of Social Media, 66 Emory L.J. 839, 843–44 (2017) (arguing that by sharing information about their child, parents create an “indelible digital footprint,” which the child has no control over); Hamming, supra note 20, at 1048 (discussing how COPPA gives parents “the ultimate authority to make choices about their children’s data privacy”). ↑

- . See, e.g., Georgia Wells, Jeff Horwitz & Deepa Seetharaman, Facebook Knows Instagram Is Toxic for Teen Girls, Company Documents Show, Wall St. J. (Sept. 14, 2021, 7:59 AM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-knows-instagram-is-toxic-for-teen-girls-company-documents-show-11631620739 [https://perma.cc/7GL6-74Q2] (illustrating that despite having knowledge of the harmful effects Instagram has on teenage girls, Facebook has made little effort to remedy these effects and frequently downplays the issue in public). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Protecting Kids Online: Testimony from a Facebook Whistleblower: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Consumer Prot., Product Safety, and Data Sec., 117th Cong. 1–2 (2021) (statement of Frances Haugen), https://www.commerce.senate.gov/2021/10/protecting%20kids%20online:%20testimony%20from%20a%20facebook%20whistleblower [https://perma.cc/L8V4-Y5N3]. ↑

- . Li & Lalani, supra note 16. ↑