Alpha Duties The Search for Excess Returns and Appropriate Fiduciary Duties

Modern finance theory and investment practice have shifted toward “passive investing.” The current consensus is that most savers should invest in mutual funds or ETFs that are (i) well-diversified, (ii) low-cost, and (iii) expose their portfolios to age-appropriate stock market risk. The law governing trustees, investment advisers, broker–dealers, 401(k) plan managers, and other investment fiduciaries has evolved to push them gently toward this consensus. But these laws still provide broad scope for fiduciaries to recommend that clients invest instead in specific assets that they believe will produce “alpha” by outperforming the market. Seeking alpha comes at a cost, however, in giving up some of the benefits of the well-diversified, low-cost, appropriate-risk baseline. Too little attention has been given in fiduciary law to this tradeoff and, thus, to when seeking alpha is prudent and beneficial for savers, and when it is not.

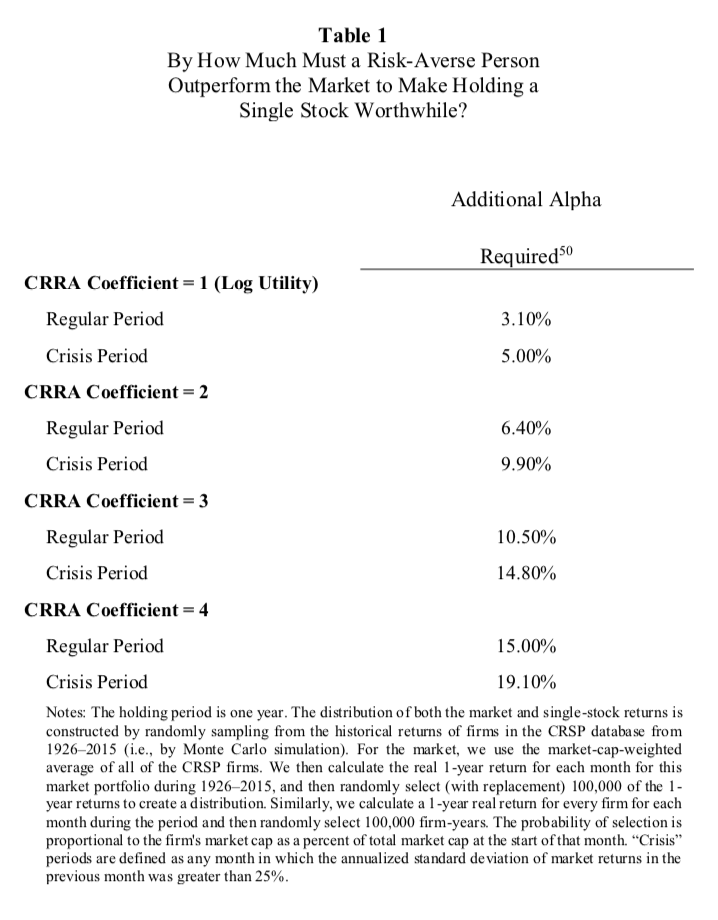

This Article begins to fill that gap by making two contributions. First, we provide the first benchmark estimates of how much alpha is required before ordinary investors would be better off departing from the consensus. For example, we estimate that a person of average risk aversion would annually need to beat the market by (i.e., obtain alpha of) between 6% and 15% before being willing to entirely forego the benefits of diversification and hold an individual stock (and that during a financial crisis such a person would need an annual alpha between 9% and 18%). Second, we consider the implications of our results for the various branches of law governing investment fiduciaries. We propose generally that fiduciaries should prudently weigh these alpha tradeoffs, and then should explain them to their clients before recommending (or executing) investments that deviate from the low-cost, well-diversified, age-appropriate exposure standard. We argue that through new technology, this kind of information can be given to retirement savers and others at quite low cost. Our results also have a variety of more specific applications. For example, our work shows that the value of diversification increases during periods of market upheaval, and therefore the duty of trustees to diversify personal trusts and employee retirement plans should likewise strengthen during such periods.

I. Introduction

Investment fiduciaries—like trustees, investment advisers, brokers, and 401(k) plan managers—help direct trillions of dollars of savings, including most of the nonhousing wealth of ordinary savers.[1] Because these fiduciaries play a variety of roles in the investment process, no single body of law applies to all of them. Nevertheless, the fiduciary duties imposed by these different branches of law are aimed at a common problem: ensuring that savers’ funds are invested prudently, with a level of risk appropriate for each investor’s circumstances and earning the highest expected return given that level of risk. The question of how to invest prudently is often viewed by retail investors as daunting, but today’s consensus is actually easily described: absent some opportunity to beat the market, one should invest in vehicles (such as mutual funds or ETFs) that are (1) well-diversified, (2) low-cost, and (3) expose one’s portfolio to age-appropriate stock market risk.[2] This consensus arose from decades of empirical and theoretical finance research. The laws governing investment fiduciaries have evolved to reflect this consensus and to push fiduciaries towards recommending (or executing) strategies consistent with it. There remains ample scope, however, for fiduciaries to recommend investing instead in specific assets that promise to deliver above-market returns. This is known in the argot of finance as “seeking alpha.”[3] Alpha investment opportunities often involve a tradeoff: investors gain expected excess returns but are required to sacrifice some of the benefits of diversification, low fees, or appropriate risk.

The laws governing fiduciaries have paid too little attention to identifying when seeking alpha is prudent, i.e., when the expected excess returns outweigh the costs of departing from the low-cost, diversified, appropriate-risk baseline. Indeed, we are not aware of any systematic attempts to provide estimates of how much alpha is needed to justify under-diversification costs or taking on the wrong level of market risk. Yet, these estimates are necessary before one can rationally distinguish beneficial alpha seeking from the imprudent chasing of excess returns. Our first contribution in this Article is to provide a methodology for evaluating these costs and then to empirically estimate them.[4]

Our estimates of the required offsetting alpha are often substantial. For example, we calculate that an investor with average risk aversion would need to expect an annual alpha between 6% and 15% before being willing to entirely forego the benefits of diversification by holding only an individual stock. Moreover, during a period of market upheaval she would need to expect an alpha between 9% and 18%. Alpha of this magnitude would easily more than double the risk premium normally paid on stock.[5]

Of course, most alpha opportunities are not so extreme as to necessitate investing solely in an individual stock. But some diversification is always sacrificed when investors adopt an alpha-seeking strategy. This is because the choice to concentrate one’s investments in an alpha opportunity implies some movement away from the portfolio that would have best diversified risk. This results in the investor bearing some risk that is specific to the alpha investments—called “idiosyncratic risk”—which could otherwise have been diversified away. Even more modest departures from full diversification can, as we later show, impose substantial losses in alpha-seeking portfolios as large as 50 stocks.

In this Article, we identify two other benefits that alpha investors sometimes sacrifice in their attempts to achieve above-market returns. Besides sacrificing the benefits of diversification, investors also at times take on too much or too little exposure to stock market risk when pursuing alpha investment opportunities. While the diversification tradeoff involves bearing a nonoptimal amount of idiosyncratic risk in return for alpha, the exposure tradeoff involves taking on nonoptimal amounts of stock market risk, often called “systemic risk,” to get alpha. Some alpha strategies involve both of these tradeoffs. For example, an investor who believes that her company will strongly outperform the market and chooses to invest all her savings in it might be exposed to nonoptimal amounts of both systemic and idiosyncratic risk. Finally, investors may be willing to pay large fees to fund managers whom they expect will deliver returns that more than offset the fee expense. Common sense tells us that a manager charging a large, supracompetitive fee must obtain alpha of at least the size of the excess fee to make it worth investing with her. But intuition provides no clear guideline for what minimum alpha is required to justify sacrificing diversification or optimal market exposure. Our results suggest the offsetting alpha is frequently substantial in real-world settings.

Having empirically estimated the minimum compensating alphas needed to justify these diversification, market risk, and excess-fee tradeoffs, we explain how fiduciary duties should take into account these alpha tradeoffs. Our results have both general implications, which apply across a variety of contexts, and more specific applications for trustees, investment advisers, brokers, and 401(k) administrators, among others.

Our goal in this Article is to make retail alpha investing “safe, legal, and rare[r].”[6] We do not propose that fiduciaries eschew all alpha opportunities, by insisting, for example, that all retail portfolios be invested in low-cost, passively managed index funds.[7] Rational investors, guided or unguided by fiduciaries, may sometimes identify credible alpha opportunities. We make no claim that such opportunities are fleetingly small. As a theoretical matter, there can be both Type I alpha errors (mistakenly pursuing alpha that will not pan out) and Type II alpha errors (mistakenly failing to pursue alpha that would deliver superior returns). And while some of our regulatory proposals might reduce Type II errors (for example, by enabling currently chilled trust fiduciaries to more easily trade off diversification for alpha), the bulk of our efforts here are to reduce existing Type I errors. Few retail investors, even when guided by investment fiduciaries, have sufficient information to justify the costs of seeking alpha. Indeed, the very magnitude of our estimates of required excess returns provides good reason for thinking that too many fiduciaries currently “seek alpha” on behalf of their clients.

Accordingly, we argue that fiduciaries who recommend or invest in alpha portfolios should be required to explicitly consider the costs of doing so. Specifically, fiduciaries should (1) estimate the costs of excessive fees, failing to diversify, and deviating from what otherwise would be optimal exposure, (2) separately estimate and justify the expected alpha from the investment decision, and (3) show that the expected alpha exceeds these costs. Fiduciaries who are recommending alpha-seeking portfolios should have a duty to explain the pertinent tradeoffs to their clients. Moreover, fiduciaries should have dynamic mechanisms in place to update their recommendations based on evolving market conditions and to keep track of their success (across clients) in predicting alpha.

Beyond this general duty to explicitly consider and explain alpha tradeoffs, our results have a number of specific implications for various financial fiduciaries. For example, our estimates show that the value of diversification increases during periods of market upheaval. We therefore argue that the duty of trustees (of both personal trusts and defined benefit ERISA plans) to diversify should be stricter during these periods. Likewise, we argue that when idiosyncratic risk is high, trustees and the courts must be more sensitive to whether trusts waiving the duty of diversification—often these are trusts holding a family business—must nevertheless be diversified to protect the beneficiaries.

Trustees are subject to a strict duty of loyalty to consider only the best interests of the trust’s beneficiaries. If trustees make bad decisions to seek alpha, therefore, those mistakes will usually arise from genuine errors concerning the costs and benefits of trying to get alpha. By contrast, there is widespread concern that due to conflicts of interest, brokers may recommend that retail clients imprudently seek alpha by buying high-fee mutual funds. These funds in turn pay the broker substantial commissions. Both the Department of Labor (the “Fiduciary Rule”) and the Securities Exchange Commission (“Regulation Best Interest”) have proposed or promulgated major regulations on this issue in the last couple of years. Because the Fiduciary Rule has been vacated, the SEC’s proposed rule is the most likely candidate to significantly alter the status quo. To determine whether a broker’s advice was unacceptably biased, the SEC’s proposed new rule would look at both (1) the broker’s conflict of interest and (2) how prudent the advice was. Our alpha analysis can help the agency refine that second question to more accurately decide when brokers are putting their own interests ahead of their clients’. In addition, to help assure that fiduciaries can perform a reasonable alpha cost–benefit assessment, we also recommend that Financial Industry Regulation Authority (FINRA) licensing tests for broker–dealers and registered investment advisers be enhanced to require would-be licensees to understand the three tradeoffs at the heart of our analysis.

We also suggest that ERISA be revamped to reduce the chance that savers in self-directed retirement accounts make ill-advised alpha investments. Specifically, we propose that the Department of Labor should issue new regulations interpreting § 404(c). These regulations would require that, in order to qualify for safe-harbor immunity, 401(k) plan sponsors periodically provide investors with an individualized portfolio analysis of potential diversification, exposure, and fee mistakes. This disclosure should include warnings about the alpha that would be required to justify the participant’s portfolio choices and an estimate of how frequently retail investors with similar portfolios have achieved alphas of that size.

Our concerns about brokers and 401(k) plan managers reflect a desire to help prevent retail investors from mistakenly seeking alpha. Research suggests this is where the most serious alpha mistakes are made.[8] Thus the gains from improving fiduciary conduct are likely to be greatest in these areas. Nevertheless, our results—e.g., the increasing importance of diversification during periods of upheaval—have important implications even for financially sophisticated parties because they are not yet widely appreciated. Moreover, our general proposal that fiduciaries should be required to weigh the costs and benefits of seeking alpha makes sense even when both the fiduciary and the beneficiary are sophisticated for the same reason that fiduciaries are held to an enforceable duty to act prudently along other dimensions in such contexts.

The costs of implementing these alpha duties is significantly lower today than it would have been in the past. With the advent of fintech like “robo-advisors,” fiduciaries can usually make reasonable estimates of the alpha tradeoffs at quite low costs. In addition, while we are cognizant that our proposed duties could add to litigation expenses, we believe the existence of an effective safe-harbor when fiduciaries recommend a passive strategy limits this concern. Likewise, following existing trust law, any litigation arising out of these duties should be focused on the process used by the fiduciary rather than a substantive second guessing of the fiduciary’s conclusion, to avoid incentivizing investors who lost money after receiving ex ante prudent advice to sue nevertheless.

Finally, we also consider the potential ramifications of our proposals for the broader economy rather than just investor protection. Our proposals aim in large part to reduce Type I errors: mistaken bets on alpha which will not pan out for the investor. Eliminating these bets will shift funds away from investment managers who try to find alpha by locating underpriced assets to passive funds which do not engage in price discovery. This in turn suggests that reducing Type I alpha errors may make asset prices less accurate. We conclude, however, that this effect is likely to be modest and self-limiting. The price discovery that would be lost is likely to be the most marginal (which is why it does not earn enough alpha to pay its costs). Moreover, if securities prices become less accurate that will make it easier to find alpha, drawing funds back into price discovery.

The remainder of this Article is divided into three Parts. Part II explains theoretically why alpha expectations might justify what otherwise would seem to be mistaken failures to diversify, minimize fees, or maintain age-appropriate exposure to equities. Part III presents our empirical estimates of the alpha required under a variety of conditions, levels of risk aversion, and different degrees of departure from optimal diversification, exposure to market risk, and competitive fees. Finally, Part IV draws out the normative implications of our analysis for three different sets of investment fiduciaries: trustees who might pursue alpha opportunities when investing trust assets, broker–dealers and investment advisers who might recommend or execute alpha opportunities for their clients, and ERISA fiduciaries who might offer alpha opportunities in 401(k) plan menus.

II. Distinguishing Between Mistakes and Tradeoffs

A. The Three Central Investment Mistakes

Retail investors often struggle to decide how best to invest non-precautionary savings.[9] Nevertheless, the consensus among economists and financial professionals is surprisingly straightforward: Absent an alpha opportunity, one should hold a portfolio which is (1) well-diversified, (2) low-cost, and (3) exposes you to age-appropriate stock market risk. The flip-side of this guidance is that there are three central investment mistakes: failing to diversify, paying high (supracompetitive) fees, and failing to expose one’s portfolio to an appropriate amount of market risk.

Failing to diversify can be an investing mistake because diversification can reduce risk at very low cost. This means that diversification allows investors to reduce the volatility of returns without reducing expected returns. As a theoretical matter, full diversification would require portfolios holding some of every risky asset—including, for example, international equities, real estate investments, and all manner of fixed income securities.[10] In practice, substantial benefits from diversification can be achieved by holding as few as ten well-selected large-cap stocks.[11] While a portfolio of this size is far less risky than a single-stock portfolio, there remain very important benefits to further diversification, particularly during periods of high volatility.

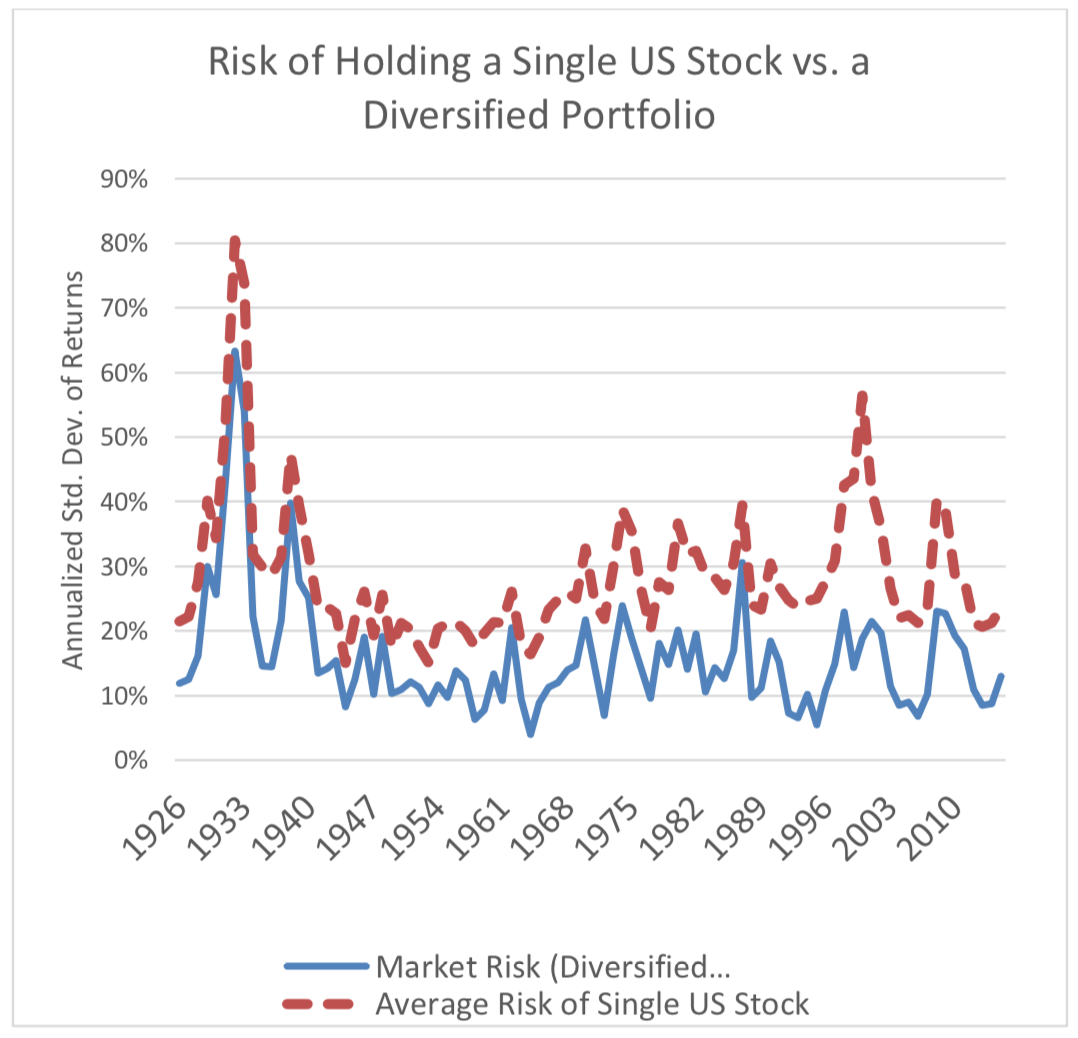

We estimate that diversification during normal times can reduce the standard measure of volatility, the standard deviation of the annual return, by 14.3%—from 33.5% on an average individual U.S. equity to 19.2% on a fully diversified portfolio of U.S. stocks.[12] What’s more, the benefits of diversification tend to be greater during periods of economic upheaval. In Figure 1, we plot the standard deviation of a diversified portfolio of CRSP stocks and the average volatility of individual stocks over time. During times of crisis, diversification reduces the standard deviation of return by 16.6%—from 51.4% on an average individual stock to 34.8% on a diversified portfolio of U.S. stocks. Failures to diversify risk are generally not as stark as investing all of your savings in company stock, but lower-bound estimates on partial failures to diversify 401(k) savings have been estimated to be equivalent to paying excess fees of 0.71% annually.[13]

Paying excessive fees can be an investment mistake because these fees eat away at the net return. For example, paying an excess fee of 2% over time can halve your retirement savings.[14] Overcharges on this order of magnitude have routinely occurred in the real world. One of us, in analyzing more than 3,500 401(k) plans (with more than $120 billion in assets), found that the top 5% had excess fees of 2.05% (with average excess fees of 0.63%).[15]

Figure 1

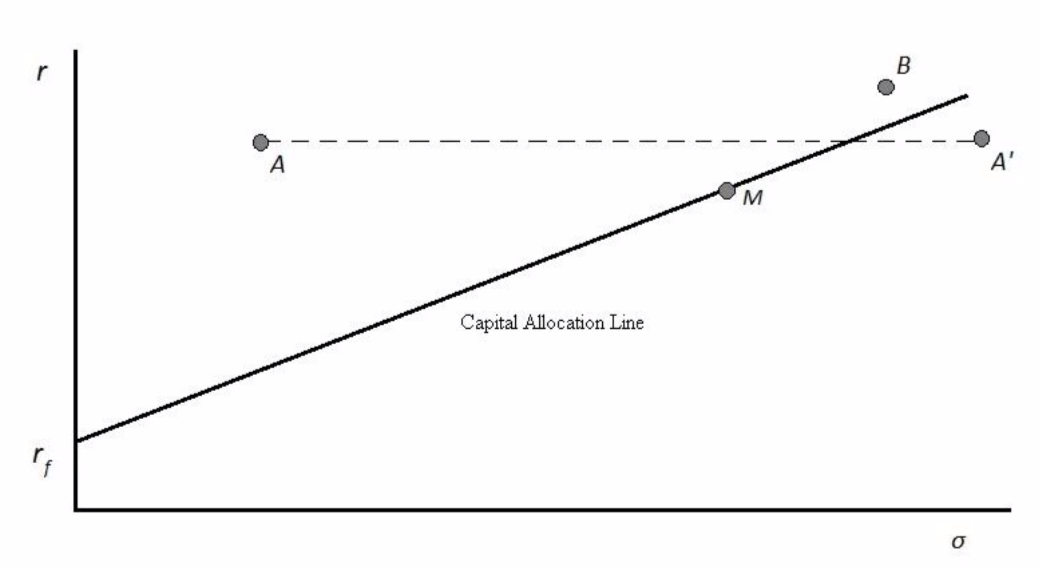

Exposing one’s portfolio to the wrong amount of market risk is a mistake because investors who take on too much or too little stock market risk fail to optimally trade off risk and return. We will henceforth call this a “beta” mistake because in the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), beta is a numeric measure of how exposed a portfolio is to market risk. A portfolio with a beta of 0 is invested in risk-free assets, while a portfolio with a beta of 1 is invested 100% in equities. Investors can make beta mistakes by exposing their portfolio to either too much or too little stock market risk given their personal risk tolerance. The two types of beta mistakes are depicted in the following figure:

Figure 2

Point A in Figure 2 depicts the expected return and risk (standard deviation of expected return) of a portfolio that optimally balances risk and return for a particular investor. In this Figure, the straight line is the “Capital Allocation Line,” which represents the set of the best achievable investment portfolios. (These are the best portfolios because in a simple CAPM model like this, one cannot beat the market.[16]) Each point on the Capital Allocation Line (CAL) is uniquely associated with a particular beta—that is, the percentage of the portfolio exposed to market risk. At the far left (the y-axis), the portfolio is composed exclusively of risk-free assets, which earn the risk-free rate, Rf. Because it has no market exposure, this portfolio thus has a beta of 0. The beta increases as one moves along the CAL to the northeast (say, from Point B to C). The curved lines represent this investor’s “iso-utilities,” the set of returns and risks for which the investor’s utility is constant. Higher iso-utility curves lie northwest because investors prefer higher expected returns and lower risk. Point A is optimal because at that point the benefits to the investor of decreasing risk by moving down the CAL are exactly offset by the value she places on the associated decrease in expected return (and vice versa moving up the CAL). Points B and C depict exposure mistakes with portfolios that place the investor on a lower iso-utility curve. Point B represents a portfolio that includes too few risky investments, given the investor’s risk preferences, while Point C represents a portfolio that includes too much risky investment.

Robert Merton in 1969 offered a simple equation to estimate the optimal portfolio exposure as a function of just three variables[17]:

where βM is the measure of optimal exposure to market risk, the Risk Premium is the amount by which the return on risky assets (say, a diversified portfolio of stocks) is expected to exceed the risk-free return (on say, government bonds), σ2 is the expected volatility of returns (captured, say, by the variance of expected stock returns), and Risk Aversion is the investor’s “relative risk aversion,” which measures how sensitive she is to risk, with 0 indicating she is risk neutral and with larger numbers indicating an increasing unwillingness to bear additional risk to get a fixed increase in her expected returns.[18] Like many economic models, Merton’s assumes that investors exhibit “constant relative risk aversion” (CRRA), which much empirical work, though not all, suggests is a reasonable approximation of real behavior.[19] We also adopt the assumption of CRRA in our empirical work below.[20] Studies estimate that the relative risk aversion of average investors is in the range of 2 to 4.[21] For example, if the risk premium is 4%, the standard deviation is 20%, and risk aversion is 2, then the optimal beta will be 50%.[22]

Merton’s investment exposure equation makes intuitive sense: an investor should, all else equal, be willing to hold a portfolio that is more exposed to market risk when the expected premium of holding risky assets is larger, and be less willing to hold a portfolio that is more exposed to market risk when the expected volatility of risky assets is higher or if the investor is more averse to that risk.

Merton’s exposure equation, however, excludes the age of the investor. If investors tend to become more risk averse as they age, then it would be natural that they would reduce their equity exposure as they grew closer to retirement. Target-date mutual funds tend to follow a variety of age-contingent strategies, such as the following “birthday rule”:

A target-date fund following the birthday rule would invest approximately 90% of its assets in equities when the investor is 20 and approximately 50% of its assets in equities when the investor is 60.[23]

To assess whether an investor is making a beta mistake, we must know what the right exposure to stock market risk would be. Reasonable people can differ over some range of exposures. However, some exposures are prima facie unreasonable judged by any of these standards.[24] For example, one study found that in 2007, roughly half of 401(k) participants in their 20s had no exposure to equity.[25] These investors are likely making exposure mistakes (akin to Point B in Figure 2) by not capturing any of the substantial risk premium on equity. Such low beta portfolios fail both the Merton and birthday rule beta standards.[26] Of course, with sufficiently high risk aversion or pessimistic market expectations, a low beta might be justified. But young people putting all their savings in money market accounts is a horrible way to save for retirement. The same study found that more than a fifth of older 401(k) participants (ages 56–65) had more than 90% of their portfolio in equities.[27] This is likely an example of the second type of exposure mistake (akin to Point C in Figure 2), as these participants are arguably exposing too many of their assets to stock market risk. However, it is admittedly harder to empirically identify this second form of beta error. Oldsters who invest almost entirely in equities are inconsistent with the lifecycle dicta but not necessarily inconsistent with Merton’s exposure equation, if, for example, the participants are not particularly risk averse and hold more sanguine views about the stock market.[28]

B. Three Alpha Investing Tradeoffs

While the last section explained how failing to diversify, economize on fees, or give one’s portfolio appropriate exposure to equities can be mistakes, this section explains how each of these deviations might instead be justified by sufficient expectations that particular investment opportunities will deliver risk-adjusted returns superior to investing in the market as a whole. We will call such opportunities “alpha” investments following popular finance parlance. The term derives from how one might measure whether an investment generates excess returns: regressing the returns of that investment on the returns of a diversified portfolio of risky assets, which we will henceforth simply call the “market portfolio.”

The regression (in simplified form[29]) is: where is the return of the investment in question in period t and is the return on the market portfolio in period t. If the investment outperforms the market, the regression will yield a positive intercept, αi, hence the term “alpha.” Note that by controlling for the investment’s correlation with market returns, , the regression adjusts for the investment’s exposure to market risk. Thus, alpha will not automatically be generated by investments with high market exposure and high expected returns.

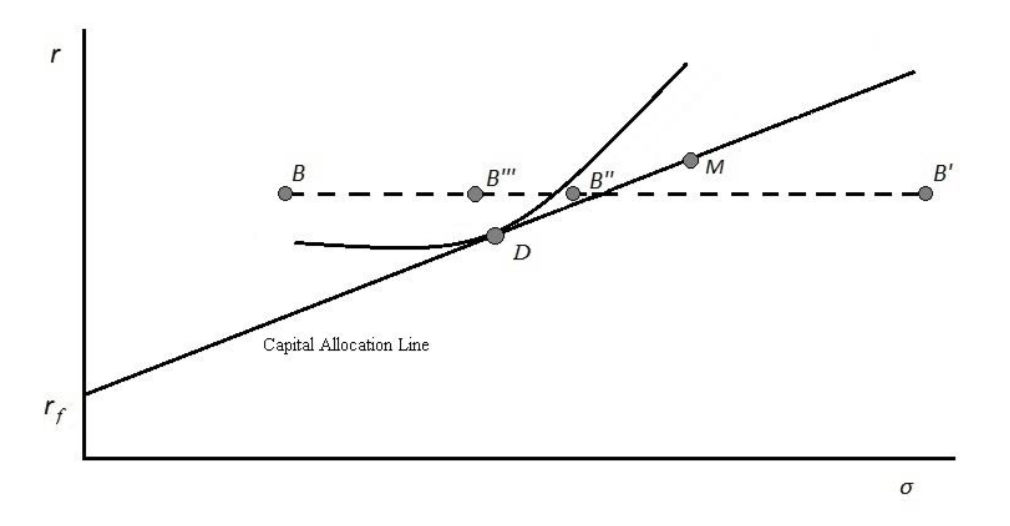

Graphically, the possibility of an alpha investment is depicted in Figure 3:

Figure 3

In Figure 2, we assumed away a number of real-world complexities, which meant that alpha opportunities were impossible. Recall that in that world, the CAL represents the set of the best achievable portfolios, which consists of (0 alpha) portfolios mixing risk-free assets and the market portfolio (Point M). If we now consider a world in which alpha opportunities can exist, alpha investments will lie above the CAL, like Points A and B in Figure 3.[30] Since Point A is to the left of Point M, it represents an investment with a β < 1. In contrast, Point B represents an alpha investment (again lying above the CAL) but with more heightened exposure to systemic risk with a β > 1. Because the risk-adjusted expected returns of these two investments exceed the expected market return, one would rationally want to hold them as part of a diversified portfolio. Indeed, the excess returns could even cause one to be willing to overweight them in a portfolio—investing more than would be necessary to diversify.

Overweighting an alpha opportunity will come at a cost, however. The investor will bear some of the risk specific to the alpha investment—its “idiosyncratic risk”—which would have been diversified away if she did not overweight it. To make this more concrete, imagine that the alpha investment opportunity is “lumpy”: the investor must invest all her savings in A or buy none at all.[31] Say A is a startup with a minimum investment equal to the investor’s savings. The additional idiosyncratic risk of investing only in A is shown in Figure 3 as Point A′, which lies horizontally to the right of A. Given its level of systemic risk, A is a positive alpha opportunity lying above the CAL, but once we account for the loss of diversification, such a lumpy alpha opportunity need not make the investor better off. Indeed, as shown in Figure 3, Point A′ lies below the CAL.

More generally, the additional expected return from investing in a lumpy alpha opportunity might or might not exceed the detrimental loss of diversification. For example, Figure 4 shows three possible outcomes of bearing the idiosyncratic risk of an alpha opportunity.

Figure 4

Point B′ is, like Point A′, an alpha opportunity that lies below the CAL once we account for idiosyncratic risk. Point B′′ is an alpha opportunity that lies above the CAL once we account for idiosyncratic risk, but it still lies below the utility the investor could achieve by investing in a fully diversified portfolio at Point D. And Point B′′′ is an alpha opportunity that lies above both the CAL and the investor’s utility from holding a diversified portfolio. Only in the last case (Point B′′′) would the investor be better off foregoing the benefits of diversification and placing all her savings in the alpha opportunity. Accordingly, it is not true that investors should always remain diversified. But the foregoing shows that sacrificing diversification requires a sufficient offsetting alpha.

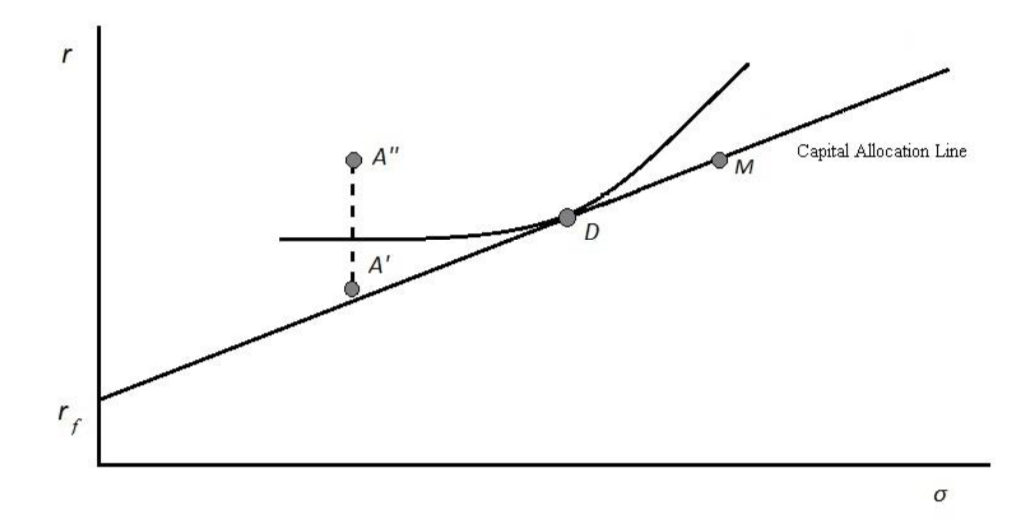

A similar argument also applies to an investor trading off alpha for moving away from her ideal beta (exposure to market risk). A lumpy alpha opportunity might force an investor to be exposed to more or less market risk than she would have chosen from the zero-alpha alternatives on the CAL. As discussed above, this deviation in exposure would reduce the investor’s expected utility. But, as before, expecting a sufficient alpha can outweigh the costs of departing from the ideal level of exposure. For example, in Figure 5, Point D reflects the optimal portfolio for an investor, absent any alpha opportunities.

Figure 5

Now imagine that the investor is offered an alpha investment that exposes her to less systemic risk than at Point D, which means she will also obtain less of the risk premium. This positive alpha investment might either be utility-enhancing or not. In Figure 5, Point A′ shows an alpha opportunity that lies above the CAL but not above the investor’s iso-utility curve. Point A′′, in contrast, shows an alpha opportunity that lies above both the CAL and the investor’s iso-utility curve. Only in the latter case would the alpha benefit outweigh the cost of having a beta that is too low given the investor’s risk preferences.[32]

Finally, the opportunity to obtain alpha might justify paying what otherwise would seem to be excessive fees. For example, imagine an investor is contemplating whether to invest in a well-diversified, actively managed mutual fund that charged f basis points in fees more than competitive passive indexes, but which is expected to generate excess returns of α basis points. Here, the fee/alpha tradeoff is relatively straightforward. The key question is whether the excess expected returns justify the excess management fees:

α > f

One should invest in the alpha opportunity only if expected alpha is greater than the excess fee. Graphically, this condition requires that the expected return of the opportunity net of the excess fee lies above the CAL.

As with the other examples examined above, our excess-fee hypothetical again isolates a single tradeoff—here the fee/alpha tradeoff. By assumption, the actively managed fund is well-diversified and non-lumpy so that the investor need not take on idiosyncratic risk and can adjust her equity exposure by mixing the fund to different degrees with government bonds. Real-world investments at times do only require considering the tradeoffs on one of these three dimensions. A mutual fund focused on one industry might sacrifice diversification without sacrificing fees or exposure. Or a high-fee target date fund (such as Fidelity Freedom Funds with expense ratios as high as 70 basis points annually[33]) might sacrifice competitive fees without diversification or exposure. Or a twenty-year-old’s 100% money market portfolio investment might sacrifice exposure without sacrificing diversification or competitive fees.[34] In each of these examples, an investor would need to have a sufficient alpha expectation to justify the isolated sacrifice of diversification, competitive fees, or optimal equity exposure.

But in many other contexts, the alpha investment opportunity will entail sacrificing some combination of diversification, competitive fees, or optimal market exposure. Actively managed funds, for example, usually both have higher fees and require some diversification sacrifices because the fund managers must pick a limited number of firms that they believe will outperform the market. Lumpy, all-or-nothing investment opportunities are particularly prone to simultaneously requiring the sacrifice of both diversification and optimal equity exposure. Starting a family business, for example, might expose an investor to both idiosyncratic risk and too much (or too little) systemic risk.[35] The key question in such situations would be whether the alpha expectation is sufficient to justify the total risk (systemic and idiosyncratic combined) that the investor has to take on. As shown graphically, this means not only that the expected return lies above the CAL when considering total risk, but the expected return lies above the iso-utility curve for the next-best market alternative.

Our theoretical analysis has focused on the CAPM and lumpy alpha opportunities, but it can easily be generalized. For example, Eugene Fama and Kenneth French have identified two attributes (or “factors”) that empirically have been associated with excess returns, namely firms with small market capitalizations and those with a high-ratio book value to market value.[36] From a CAPM perspective, the excess returns that tend to be garnered by small-cap stock or high book value stock can be interpreted as an “alpha,” which would lead rational investors to want to overweight small-cap stocks in their portfolios. But as depicted in Figure 3, this overweighting will cause at least some diversification loss, pushing up the portfolio risk, possibly inside the CAL (as in Point B′). Rational investors would not want, however, to overweight in ways that reduce utility below the iso-utility line.[37]

How much to overweight becomes a central concern when the alpha opportunity is not a lumpy, all-or-nothing investment choice, but can be chosen by an investor in various increments. An actively managed mutual fund with high management fees is a quintessential example of a non-lumpy investment because the investor can vary the proportion of her portfolio that she chooses to invest in the high-fee fund. An opportunity to start a family business, in contrast, is a much more lumpy investment as it might require committing a substantial proportion of an investor’s portfolio. Minimum investment requirements imposed by various types of funds (including hedge and private equity funds) also can make investment options a lumpy or discrete portion of a portfolio.

Theory tells us that when a non-lumpy alpha opportunity arises, rational investors would want to “tilt” or overweight their portfolios toward the investment.[38] The extent of tilt will depend on the particular costs and benefits (and will be empirically estimated in the next section). When the alpha opportunity is lumpy, the optimal all-or-nothing investment choice will be “nothing” if the alpha is not sufficient to justify the incremental diversification, exposure, and fee losses.

III. Empiricism

The last Part explained as a theoretical matter why investment opportunities with expectations of sufficient above-market returns could justify reduced diversification, high fees, or non-optimal exposure to market risk. In this Part, we turn from theory to numbers—to estimate how much alpha is required to justify a failure to diversify, economize on fees, or obtain age-appropriate exposure to market risk. The estimates (and the ability to make such estimates) are important because, as we will argue in Part IV, fiduciaries who make one of the presumptive mistakes without considering whether they have the requisite alpha or who do not have a sufficient basis for believing that an investment opportunity has a sufficient alpha might, in a variety of contexts, be held liable.

The analyses below should be thought of as benchmarks, not the definitive estimates of the requisite alpha, because our results are dependent in part on our assumptions, including about the investor’s other sources of income, the investor’s preferences, and, in some analyses, the use of CAPM. An analysis by an actual fiduciary would need to be tailored to the investor’s life circumstances including her sources of income other than investments, age, risk preferences, etc. In addition, as noted above, we make the common assumption that the investor’s preferences can be represented by constant relative risk aversion. Financial economists, however, have suggested several other models of risk aversion, which help explain swings in asset prices during recessions and booms. These models typically posit larger increases in risk aversion (or something akin to that) during recessions than those implied by constant relative risk aversion.[39] Using these models would further increase the estimated alpha required to forego diversification during recessions and periods of market upheaval.[40]

With respect to trading off alpha for taking on non-optimal amounts of market exposure, we invoke CAPM’s results to understand how increasing market exposure changes expected returns and overall risk.[41] Although CAPM remains widely used, there is a broad literature arguing that it is incomplete and contending that multifactor models should be used instead.[42]

A. Excess Fees

The required alpha to justify a mutual fund’s excess fees is the easiest to estimate. As mentioned in the last Part, the required alpha is simply the amount by which the fees exceed the competitive expense ratio charged by other funds offering well-diversified portfolios of similar investment classes. It would be a “nirvana fallacy” mistake to assume that the competitive market can offer diversified portfolios at zero cost. For domestic equities, there are a host of diversified funds and ETFs that annually charge less than 25 basis points. While for emerging markets, the competitive expense ratios are somewhat more, but many are offered with fees of less than 50 basis points.[43] It is only the excess above the competitive price that needs to be traded off against alpha. When considering combination-fee tradeoffs, one can begin by simply subtracting the excess fees from the expected alpha and then asking whether the alpha net of excess fees is sufficient to justify the shortfall in diversification or exposure. Thus, in considering the required alphas estimated below, they should be construed as the net alphas that are required to take on deviations from optimal diversification or exposure.

Various studies have reported negative average mutual fund alphas (ranging between –0.45% and –0.60% per year).[44] Nonetheless, some scholarship suggests that winning bets on actively managed higher-fee mutual funds do exist for a small percentage (less than 3%) of funds.[45] However, studies suggest that such alpha over-performance is not persistent.[46] For example, a recent study found that of the top half of funds in 2010, only 4.47% were able to stay in the top half for five years, and only 0.28% stayed in the top quarter.[47]

B. Diversification Costs

Estimating the required alpha to justify sacrificing diversification is the central empirical motivation for this Article. Imagine that you had a lumpy choice of either investing all your savings in a single stock representative of public U.S. companies (say, your company’s) or in a fully diversified mutual fund of U.S. equities. How big would the expected alpha on the single stock have to be to justify the obvious loss in reduced idiosyncratic risk that could be achieved through diversification?[48]

To answer this question, we examined historical data on U.S. stocks from the mid‑1920s through 2015. We calculated the utility of investors with various levels of risk aversion from holding either a diversified portfolio or a single stock over the course of one year. We then estimated how much alpha the individual stock must generate before an investor would prefer the individual stock with its higher alpha-boosted returns but higher risk to the diversified portfolio. We made separate calculations for periods of market upheaval because idiosyncratic risk rises during economic crises,[49] meaning that the required alpha will usually rise as well. We defined these crisis periods as those in which the annualized standard deviation of market returns over the previous month was 25% or more. (Further details on our calculations are included the following table.)

Table 1 teaches several important lessons. First, we can see that rational investors, even during regular periods, would require quite substantial alphas before foregoing the benefits of diversification. For investors with moderate risk aversion (measured by CRRAs between 2–4), the required excess annual returns by which an investment would need to be expected to beat the market ranges from 6.4% to 15.0%.[51] Intuitively, investors with higher levels of risk aversion demand greater increases in expected return to bear the same increase in risk. Thus, they will require a higher alpha before they are willing to bear the same amount of additional idiosyncratic risk.[52] As we discuss in detail, these large alphas are consistent with the increasing emphasis on the importance of diversification in fiduciary law, particularly in trusts, over the last 30 years.

Second, we see from the table that the alpha required during crisis periods is substantially larger than during regular (non-crisis) periods. For investors with moderate risk aversion (again measured by CRRAs between 2–4), the required alpha to forego diversification benefits ranges from 9.9% to a whopping 19.1%, ballooning during these crisis times. This is primarily because idiosyncratic risk rises during crises. During ordinary periods, the idiosyncratic risk (measured as a standard deviation of return) is 27.4%, while during crisis periods, the standard deviation is 37.8%. As idiosyncratic risk increases, the benefits of diversification increase and therefore the alpha required to get investors to give up diversification increases as well.[53]

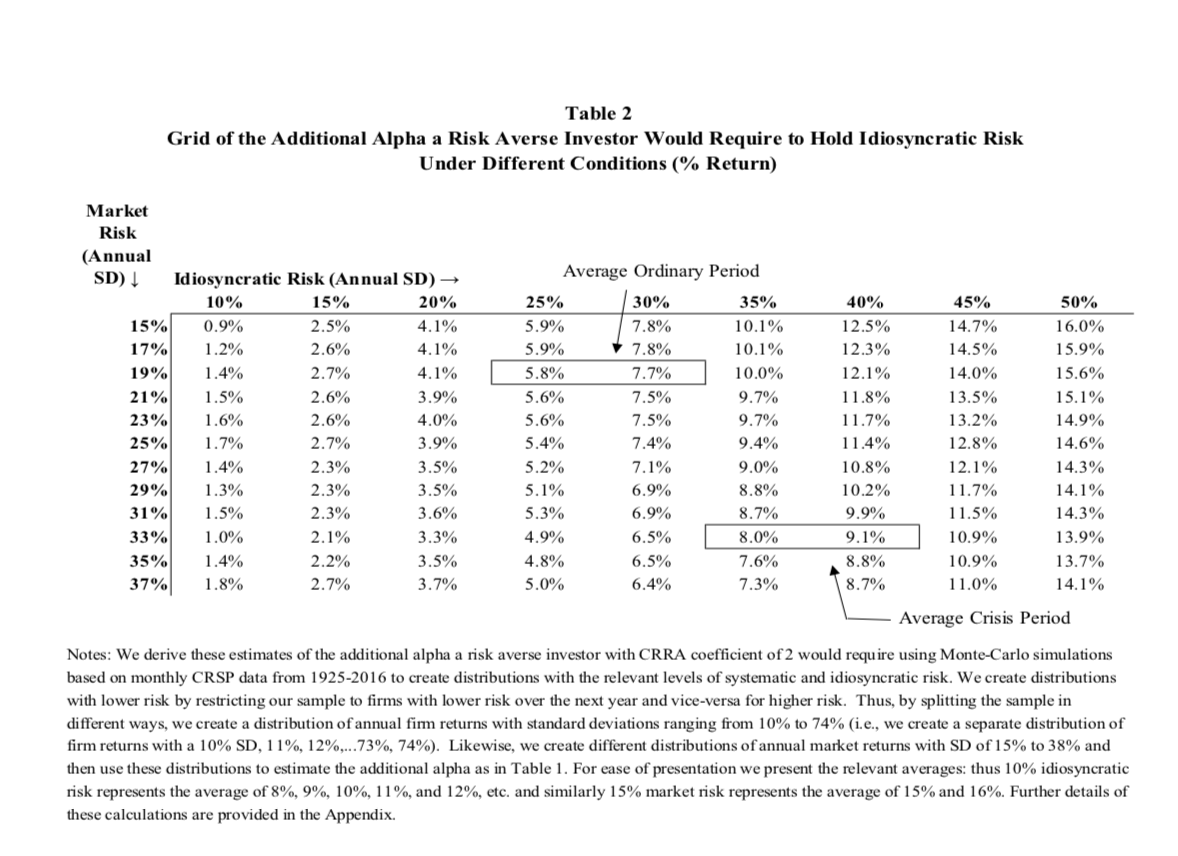

Table 2 estimates the required alpha that would be necessary to compensate for bearing different levels of idiosyncratic risk, given different levels of systemic risk.

Table 2 helps us more clearly see why the required alpha rises during crises as both systemic and idiosyncratic risks rise, pushing southeast in the table. But the table is also useful in that it allows a more nuanced and specific assessment of how much annual alpha is required in particular circumstances. The market risk at any time can be estimated by viewing forward-looking market volatility measures (such as the VIX), and the idiosyncratic risk can be similarly estimated for any stock with traded options.[54] Using these two inputs, one could assess what alpha was necessary for more particularized situations. Thus, for example, we estimate that an Enron employee with slightly below-average risk aversion (CRRA = 2) who forewent diversification to invest her retirement savings entirely in company stock would need to expect at least an average alpha of 10.8%.[55] In fact, we have created an online widget that lets anyone plug in three variables (a level of CRRA risk aversion, a level of market risk, and a level of idiosyncratic risk for a particular stock) to determine the alpha required to take on the additional idiosyncratic risk.[56]

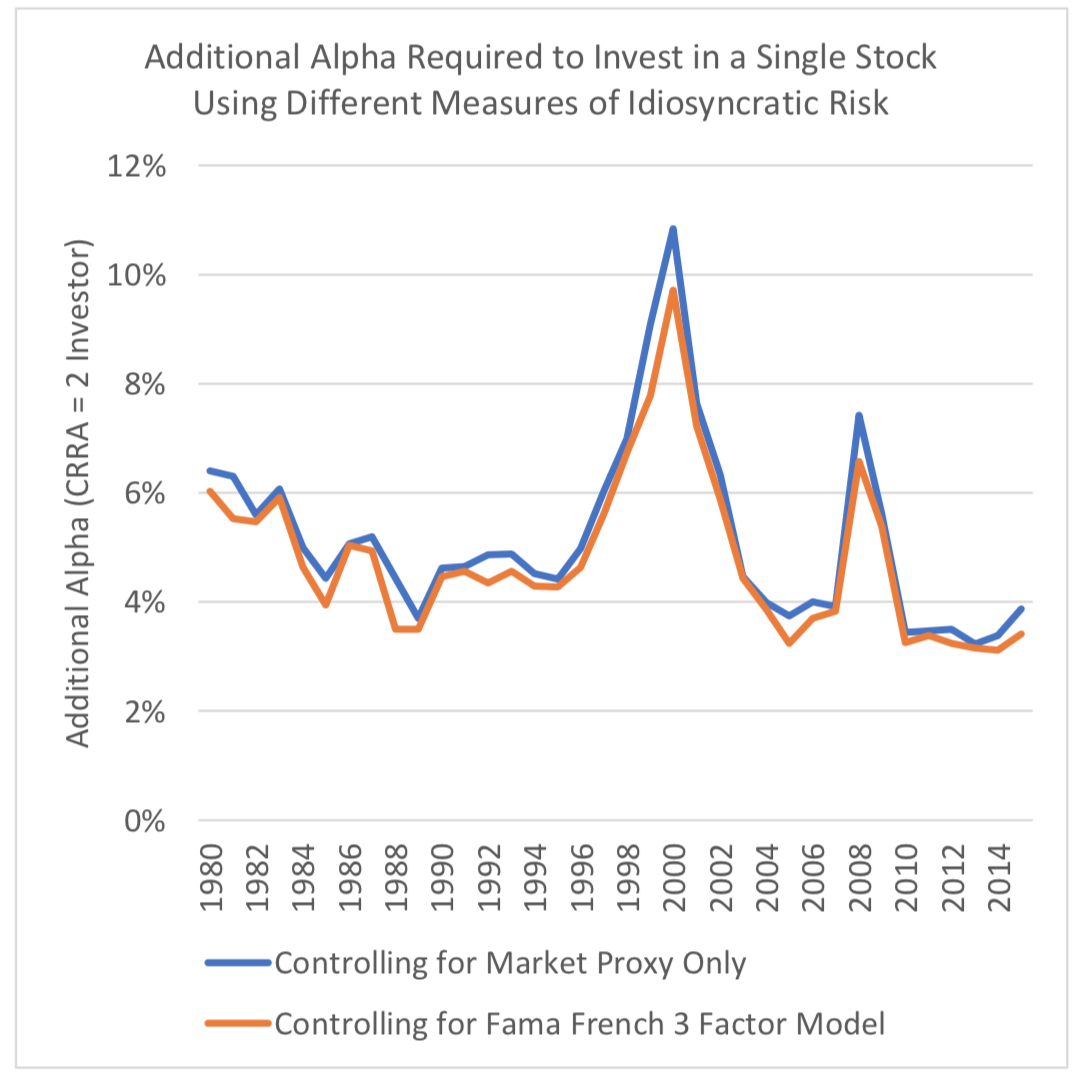

The results above barely budge if we instead use the Fama–French three-factor model to measure the amount of uncompensated risk inherent in holding an average stock. As noted above, Eugene Fama and Kenneth French have shown that a stock’s relative market capitalization and the ratio of its book value to market value also help predict its return, along with market exposure. They hypothesize that a stock’s market exposure is an incomplete measure of the kinds of undiversifiable risk faced by its owners, and these other two factors proxy for these other risks, which help drive returns.[57] Nevertheless, when we use the Fama–French model to measure how much alpha an investor would demand, the results are basically unchanged:

Figure 6

Of course, most alpha investment opportunities are not quite so extreme as to require investing in a single stock. While the previous tables have focused on all-or-nothing tradeoffs, in most real-world settings investors are only required to partially de-diversify in order to reap higher expected returns. For example, some investors may invest all their savings in an actively managed mutual or hedge fund that invests in several stocks that the fund’s managers believe will outperform the stock market generally. Investing heavily in sector funds also sacrifices some potential diversification because the investor’s portfolio bears the risk particular to that industry instead of diversifying it away by investing in the other sectors of the economy. These partially diversified positions also require offsetting alphas (but not as much as alpha opportunities that invest in a single stock).

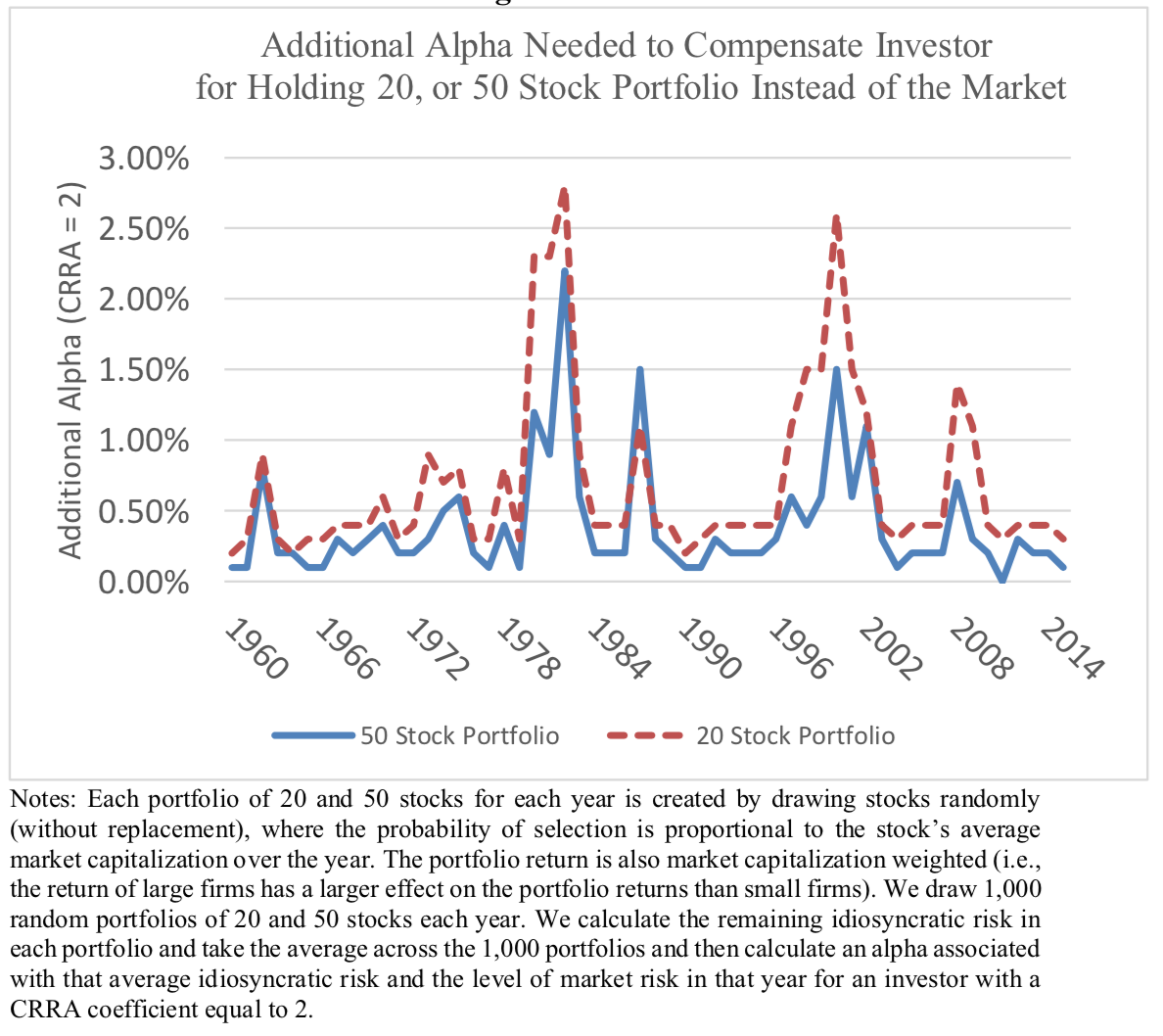

To investigate how much alpha is required to compensate an investor for only partially diversifying, we perform another set of simulations based on historical data. In particular, in each year from 1926 to 2015, we randomly choose 1,000 representative portfolios with a given number of stocks (e.g., 20 stocks or 50 stocks). We then calculate how much idiosyncratic risk remains in these partially diversified portfolios and, using the figures underlying Table 2, convert this level of idiosyncratic risk into an alpha. [58] We plot the results in Figure 7 for the 20- and 50-stock portfolios from 1960 to 2015:

Figure 7

Figure 7 reveals that the required level of compensating alpha is, as theory would predict, substantially lower for partially diversified portfolios. While the average annual compensating alpha for a single stock over this time period is 5.71%, we find that this drops to 0.70% when investing in 20 stocks and to 0.39% when investing in 50 stocks. But importantly, the figure shows that even with 50 stocks there are 5 separate years where the required offsetting alpha is at least 1%. It is often suggested that investors can achieve the most important benefits of diversification by investing in just 10 or 20 different stocks,[59] but our estimates show substantial variation in the requisite alpha necessary to justify even relatively small departures from full diversification. During periods with relatively high systemic risk, then, adding even small amounts of potentially diversifiable idiosyncratic risk can necessitate substantial alphas. If the normal risk premium for holding non-diversifiable market risk is 4%, then the alpha-adjusted risk premium required for adding on just the idiosyncratic risk of a 50-stock portfolio is frequently 25% higher.[60] The takeaway here is that even partially diversified investment opportunities can at times require relatively substantial alpha to make such an investment utility-enhancing. As explained below, these results suggest that the usual rule of thumb about how much diversification is “enough” may be too loose.

C. Exposure Costs

Finally, we estimate the “beta” costs of being non-optimally exposed to the equity risk premium. As discussed above, beta costs can come in two forms: one can have too little equity exposure (as when a 23-year-old invests all her savings in money market funds), or one might have too much equity exposure (as when a risk-averse 70-year-old with a modest nest egg invests all her savings in stock). And while beta costs often also require sacrificing diversification when an alpha investment is lumpy, in this section we isolate the compensating alpha required to offset having to take on inefficiently high or low beta. (In other words, we assume that there are no diversification or excessive-fee losses entailed in the investment.)

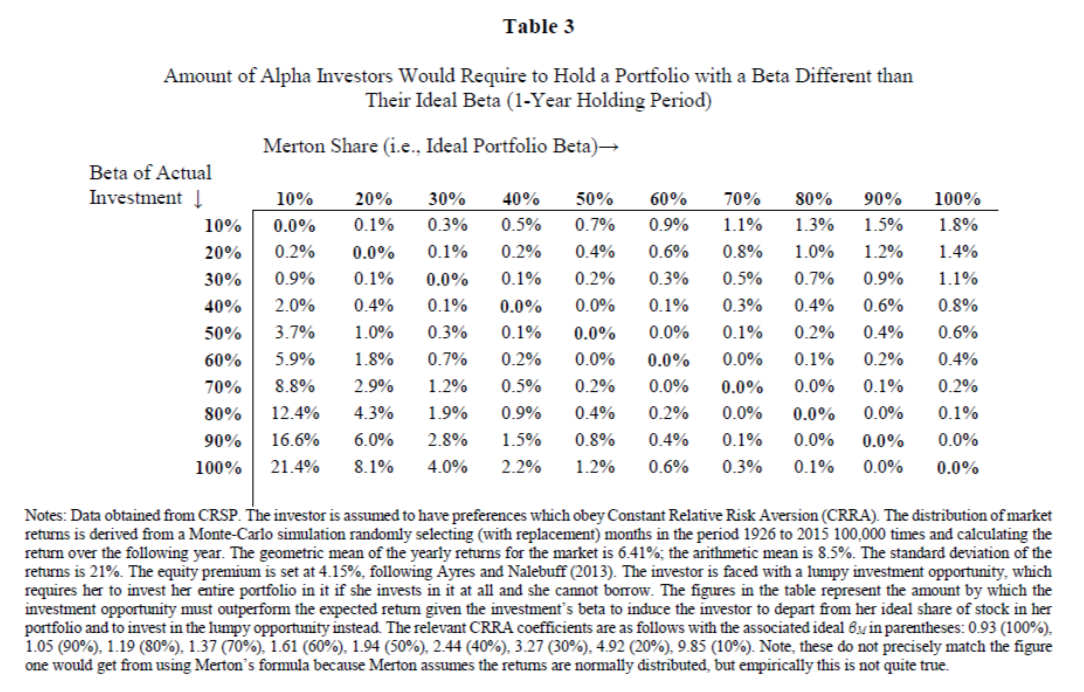

As emphasized above, the notion of a beta error is only comprehensible if we have a background idea of what an optimal exposure to equities would be. That optimal level is intuitively a function of a particular investor’s level of risk aversion, which might (or might not) increase as she ages. In the following table, we assume that the optimal equity exposure is determined by the Merton share described above (as βM) so that investors with higher constant relative risk aversion would optimally choose to have lower exposures to equity.[61] Applying a historical distribution of returns to the market portfolio and risk premiums, we can calculate the ideal β for an investor with any level of risk aversion. Taking investors with ideal β’s of 0.1, 0.2, . . . , 0.9, and 1 as examples, we then estimate how much alpha they would require to depart from their ideal β in Table 3 following.[62]

In Table 3, one can see the offsetting alphas from having too much or too little exposure to equities.[63] The table shows that investors are more sensitive to beta deviations as they become more risk averse. For example, an investor with a βM = 0.3 would need an annual alpha of 0.3% before making a beta deviation of 0.2, while an investor with a βM = 0.7 would only need an alpha of 0.1% for making that-sized beta deviation. More generally, the alpha required for putting risk-averse investors in high beta investments are substantially higher than the alphas required of relatively risk-neutral investors in low beta investments. Hence, we see in the diagonal corners of Table 3 that the alpha required for putting a βM = 0.1 investor into a β = 1 portfolio is a whopping 21.4%, while the alpha required for putting a βM = 1 investor in a β = 0.1 portfolio is only 1.8%. As we discuss below, this result accords with how fiduciary law has generally approached the question of beta mistakes: not investing aggressively enough is harmful, particularly over time, but the most damaging beta mistake in the short term is exposing a highly risk-averse client—a widow who is the sole beneficiary of a small trust set up for her maintenance—to too much risk.

In most real-world contexts, the estimates in Table 3 for lumpy investments should be seen as lower bounds on the required alphas for portfolio deviations from optimal betas. This is because the lumpiness of the investments usually entails some degree of diversification loss. The opportunity to invest a substantial portion of your portfolio in a friend’s start-up, for example, might force your portfolio above your optimal beta and expose your portfolio to idiosyncratic risk. Accordingly, in such circumstances it will be necessary in calculating the required alpha to account for (and offset) both types of losses. For example, if investing all of your savings in a friend’s start-up caused you, a βM = 0.5 (↔CRRA ≈ 2) investor, to take on β = 1 portfolio and expose your portfolio to average non-crisis idiosyncratic and market risk, then you would need at least an alpha of 7.6%: 6.4% to compensate for the diversification loss (as shown in Table 1) and an additional alpha of 1.2% to compensate for the beta loss (as shown in Table 3).[64]

D. Tilting Mistakes

While most of our foregoing estimates concern discrete investment opportunities, there are many real-world opportunities that give investors the option of varying the proportion of their portfolio that is invested. In such “non-lumpy” circumstances, theory suggests that an investor will want to “tilt” her portfolio toward alpha opportunities by overweighting the portfolio share of the alpha opportunity, even though this overweighting will expose the investor to some idiosyncratic risk. In this section, we investigate how much a person should invest in a non-lumpy alpha opportunity given two key variables: the size of the alpha and the total risk of alpha opportunity.[65] As with beta mistakes, tilting mistakes can come in two varieties: (1) an investor can under-tilt by putting too small a proportion of her portfolio in the non-lumpy alpha opportunity or (2) the investor can over-tilt by putting too large a proportion of her portfolio in the alpha opportunity.

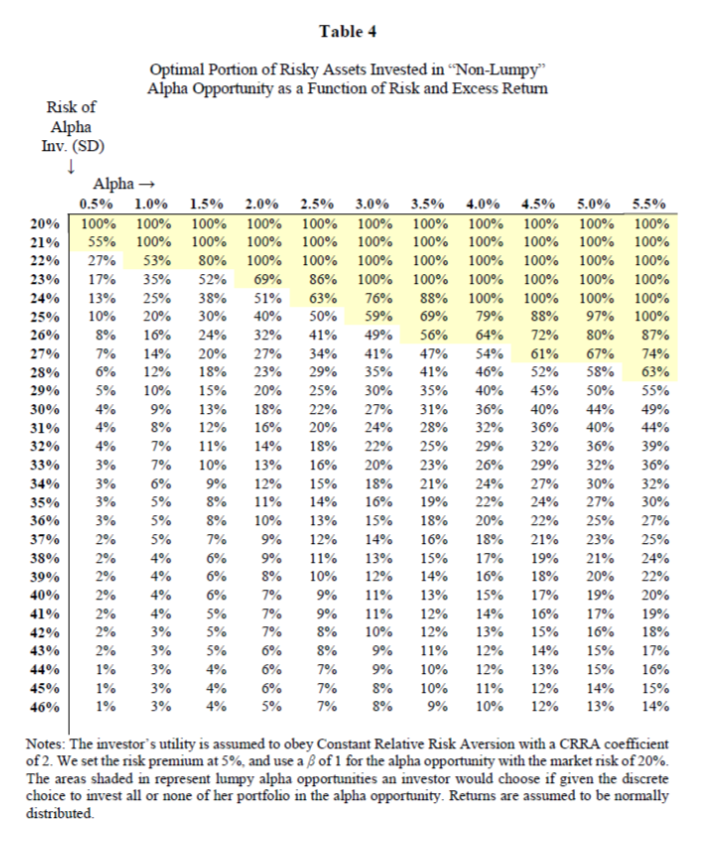

Table 4 estimates the optimal tilt for an investor with moderate risk aversion (CRRA = 2) depending on the size of the alpha and the riskiness of the alpha opportunity, fixing the riskiness of the market (20% standard deviation), the β of the alpha opportunity (β = 1), and the risk premium for holding the market portfolio instead of risk-free assets (5%).

Table 4 shows that when 100% tilting would expose the investor to relatively small additional idiosyncratic risk, that relatively small alpha is necessary to induce an investor to want to put all of her portfolio in the alpha opportunity. For example, if going full-tilt only increases the total risk standard deviation of return by 1 percentage point (from 20% to 21%), then Table 4 shows that an alpha of just 1% would be sufficient to induce an investor to want to invest all of her portfolio in the alpha opportunity (even though she has the non-lumpy option to invest a lesser proportion).

But as the cost of tilting increases, investors will optimally invest a lower proportion of their portfolio in the alpha opportunity. Thus, we see if a 1% alpha opportunity has an associated total risk of 30%, an optimal investor (with a CRRA risk aversion of 2) should want to invest only 9% of her portfolio in the alpha opportunity. Under these circumstances, investing less than 9% of one’s portfolio would represent an under-tilting error, while investing more than 9% would represent an over-tilting error. We conjecture in real-world settings that over-tilting is the more important error. Retail investors who are not aware of the size of the gains from diversification frequently hold only a few stocks, or even only stock in their company. Even if these investors believe the stocks will outperform the market, they are probably making a mistake by treating those stocks as though they require large minimum investments (as a share of the investor’s portfolio). Although there are situations in which the alpha is so great that one would want to hold only the alpha investment even if it is “non-lumpy”—as in the northeast corner of Table 4—these situations will be relatively rare in the real world, because they require very large alphas (or very small idiosyncratic risk).

Stepping back, we have provided in this Part some of the first estimates of the minimum alphas that are required to offset diversification and beta losses,[66] as well as excessive fees. But for a variety of reasons, these estimates should be viewed as ballpark measures. For example, our estimates on diversification losses assume that investors have a particular form of (constant relative) risk aversion. Other types of risk aversion are less mathematically tractable but might be more empirically relevant and give rise to alternative estimates.[67] In addition, we have not modeled investors’ exposure to the market through their human capital.[68] Also, our estimates have assumed that investors “know” a variety of variables, including the alpha of particular investment opportunities and the levels of idiosyncratic and market risk. But in many situations, investors are likely to have varying degrees of confidence in their beliefs about alpha and these other variables. While the expected market volatility is derivable from options prices,[69] investors’ beliefs about idiosyncratic risk and alphas might be less precise. For risk-averse individuals, less precise beliefs about alpha should militate toward demanding even higher alphas because uncertainty about alpha is another form of risk.[70]

Even with these caveats, the take-home result of this section is that investors need to have reasonable expectations that an investment will substantially beat the market before being willing to take on diversification, beta, and excess-fees losses. Financial economists normally expect that stocks will beat government treasuries by somewhere between 3 and 6 percentage points. But an investor who puts all her savings in a single stock would need an additional alpha of at least twice this amount (6.4% in Table 1) and during crisis periods an alpha of nearly 10% annually. Moreover, if the opportunity requires the investor to pay excessive fees, the alpha should be calculated net of this excess, and if the investment necessitated a beta deviation, an additional alpha to offset the exposure loss would be required. Investment opportunities with alphas of these magnitudes are not impossible, but they are likely to be sufficiently rare that the law should be quite concerned when fiduciaries advise clients to take on substantial diversification, beta, or excess-fees costs, or in the case of trustees, directly invest the beneficiaries’ funds in that manner.

Our concern with the mistaken pursuit of alpha that is not cost justified (Type I errors) leads us to argue below for interpreting fiduciary law to more robustly deter these mistakes. Our goal is, of course, to protect investors. One might object, however, that more complex interests are also at stake. Investors who make alpha bets after seeking out new information or engaging in fundamental valuation of firms help align prices with the discounted

cash-flow value of the businesses. This in turn, over the long run, allows the capital markets to allocate scarce capital to the most productive enterprises. Fiduciaries who guide investors to the low-cost, well-diversified baseline by investing in various passive mutual funds and ETFs, by contrast, are to a degree free‑riders who do not contribute to price accuracy. Thus, arguably, our proposed reforms could reduce price accuracy and, eventually, economic performance.

We take this concern seriously but believe it will have limited effect for a few reasons. First, to the extent our proposals are aimed at retail investors, we think such investors probably do relatively little in the way of price discovery. If we can reduce the number of people who use the broker window in their IRA or 401(k) plans to invest in individual stocks, this will have little effect on how closely market prices track fundamental value. Indeed, because most of these individuals are likely to be “noise traders,”[71] convincing them to stop investing in individual stocks might even improve price accuracy.

Reducing investment in high-fee, actively managed mutual funds, by contrast, might well marginally reduce price accuracy. It is worth distinguishing between two types of actively managed funds: (1) those which, after fees and de-diversification costs, break even compared with comparable passive indices and (2) those which, after fees and de-diversification costs, perform worse than those indices. The funds in the latter category cost more than they contribute in price accuracy.[72] Crimping investment in these funds will improve investor welfare while likely having a modest effect on price accuracy. Our proposal is not intended to limit investment in funds in the first category, which charge higher fees but obtain enough alpha to exactly offset those costs. These funds may do a significant amount of price discovery.[73] To the extent fiduciaries eschew these break-even funds under our proposals, say because recommending investing in passive funds is a clearer way to avoid potential liability, a meaningful amount of price discovery may be lost.

Nevertheless, if price accuracy does decline, the problem will be largely self-correcting. As price accuracy falls, the expected gains from making alpha bets through fundamental valuation or information discovery will increase. This will induce direct investors, and fiduciaries under our rules, to direct more clients into funds making alpha bets based on fundamental valuation or information discovery. Finally, in an era when the financial sector has earned as much as 40% of total corporate profits,[74] many people are reasonably concerned that we have devoted too many resources to finance and that many of the activities that are profitable for financial-sector firms do not have commensurate social gains. Reducing the investment in funds that do not earn enough alpha to outweigh their excess fees and the costs of failing to diversify might then be thought of as a salutary reduction in excessive resources devoted to finance.

IV. Legal Implications

The last two Parts analyzed the theoretical and empirical tradeoffs that often arise when investors pursue alpha investment opportunities. This Part develops the legal implications of these tradeoffs. More particularly, we describe what we call “alpha duties,” the legal duties that investment fiduciaries should have before recommending alpha investments or investing in such opportunities on their clients’ behalf.

This Part is organized around three types of fiduciaries: (a) trustees, (b) broker–dealers and investor advisers, and (c) 401(k) plan managers. The next section on trustees lays out the core limitations concerning recommendation and actual investment in alpha opportunities, while the subsequent sections explore specialized questions regarding upgraded licensing requirements of broker–dealers and investment advisers as well as “alpha-tized” 401(k) menu selections and fintech warnings.

A. Trustees

Trust law is typically thought of in the context of personal gratuitous transfers.[75] These kinds of trusts are important: U.S. banks and trust companies held more than $600 billion in assets as trustees of personal trusts in 2017.[76] This figure understates the true size of personal trusts because it does not include those with trustees who are individuals (rather than entities), and other commentators have estimated that personal trusts have at least $1 trillion in assets.[77]

In addition, much of what we say here applies to retirement accounts governed by ERISA. As the Supreme Court recently observed in Tibble v. Edison International:[78] “We have often noted that an ERISA fiduciary’s duty is ‘derived from the common law of trusts.’ In determining the contours of an ERISA fiduciary’s duty, courts often must look to the law of trusts.”[79] As of 2014 there were about $5.3 trillion invested in defined contribution ERISA plans (mostly 401(k) plans) and $3.0 trillion in defined benefit plans (traditional pension plans in which the employer promises a fixed payout schedule).[80] Again, these accounts constitute the majority of ordinary Americans’ savings not invested in housing. We discuss some issues peculiar to 401(k)s in the final section of this Part.

In the rest of this subpart, we discuss the basics of trust law, including the trustee’s fiduciary duties of loyalty and prudence. The duty of prudence is in turn broken down into many subsidiary duties when applied to trust investing. We address the implications of our results for three of these subsidiary duties, which are well-recognized under current law: (1) the duty to diversify, (2) the duty to take on only risk appropriate for the beneficiary’s circumstances, and (3) the duty to incur only reasonable costs. The law regarding the first two of these duties has evolved substantially over the last thirty years. In their modern form, these three duties restrain trustees from making the three central investment mistakes when there is no justification for doing so. The development of the law has been less complete, however, in using these duties to ensure alpha seeking is worth the cost, and we show how our work can help trustees and courts make better decisions on this question.

We then argue that taken together these three duties impose what we have called “alpha duties” on trustees. Under these duties, trustees should calculate the cost of a given alpha-seeking strategy in terms of under-diversification, excess fees and costs, and non-optimal exposure, and compare that to a reasonable estimate of the expected alpha to decide whether a strategy is prudent. These alpha duties accord with the Third Restatement’s approach to prudent active investment.[81] The duties also serve as a model for what we would propose for fiduciaries in other situations.

1. Trust Basics.—A trust separates the legal and beneficial ownership of property. The trustee is by default given all the powers over the property of an owner to manage and invest it for the advantage of the beneficiaries.[82] It should also be noted that most trust law is default law—i.e., the person creating the trust (the settlor) can usually opt out if she chooses—but the default is nevertheless highly influential.[83]

2. The Trustee’s Fiduciary Duties.—A trustee has two main duties: (1) loyalty and (2) prudence, as well as a variety of subsidiary obligations, which are “applications of prudence and loyalty.”[84] Trust law has long contained a stringent duty of loyalty that requires the trustee to manage the trust solely in the interest of the beneficiaries.[85] While there have been incremental changes, the scope of the duty of loyalty has been largely stable for over a century.

3. Prudence.—By contrast, the duty of prudence, as it applies to trust investments, has undergone substantial changes over the last thirty or so years. Prior to the 1980s, most states limited the types of property a trustee could invest in either through formal lists or the “constrained prudent man rule.” Both doctrines channeled trust property into bonds or real property and banned investment in some or all equities.[86] The rules frequently prevented trustees from giving beneficiaries enough exposure to equities—i.e., the rules forced trustees to make beta mistakes by investing with too low betas—and during the high inflation periods in the 1970s and 1980s, bond-heavy trust portfolios floundered. In addition, it was unclear in some states whether there was a duty to diversify.[87] These rules ran counter to the finance research and practice, discussed above.[88]

Observing these failures, trust-law reformers succeeded during the 1990s in breaking down the previous constrained approach. The 1994 Uniform Prudent Investor Act (UPIA), eventually adopted in 45 states, abrogated bans on investing in categories of risky assets and instead requires the trustee simply to “invest and manage trust assets as a prudent investor would, by considering the purposes . . . [and] circumstances of the trust.”[89] The remaining states adopted similar measures, although not based on the UPIA language.

Although the prudent investor standard provides useful flexibility, some commentators have complained that it fails to prevent trustees from investing in portfolios that are too risky for the beneficiaries.[90] Likewise, while the UPIA clarified the importance of the duty to diversify, it provides relatively little guidance as to how much diversification is enough or when circumstances make a relatively undiversified portfolio prudent. Our results can help to address these problems by fleshing out the meaning of appropriate risk and the duty to diversify under the Act.

4. Subsidiary Duties: Prudent Diversification.—Under the UPIA (and the Restatement), the trustee has a duty to diversify the trust portfolio “unless the trustee reasonably determines that, because of special circumstances, the purposes of the trust are better served without diversifying.”[91] The official comment lists two common circumstances in which not diversifying might be prudent: (1) if the trust consists in part of property with a low tax basis or (2) if the trust contains a family business. In addition, trust law permits prudent active management of trust assets,[92] which entails not fully diversifying.

Although the UPIA does not necessarily set up a formal shifting of the burden of persuasion or of going forward, the text of the rule, at a minimum, makes it incumbent on the trustee to make a showing that her decision was reasonable, if she fails to diversify.[93] But that begs the question: how much concentration of the trust portfolio must a complaining beneficiary show before the trustee owes an explanation? The leading textbook in trusts and estates notes the received wisdom:

In light of the studies showing that diversifying into 20 to 30 unrelated large capitalization stocks removes most of the diversifiable risk from a stock portfolio, a good rule of thumb is that a concentration in a single security of more than 5 percent requires explanation.[94]

Our work shows that during volatile periods when idiosyncratic risk is high, this rule of thumb is probably too loose. A random, market-weighted, portfolio of 50 stocks will have few or no stocks with concentrations above 5%, but will still impose high costs during volatile periods. These under-diversification costs have been up to 150 basis points per year for moderately risk-averse beneficiaries during unsettled periods.[95] By comparison, during calm periods like 2003–2007 and 2011–2015, a random market-weighted portfolio of 10 stocks would have imposed much smaller—although still important—average costs of about 60 basis points for the same investor. This is true despite the 10-stock portfolio raising serious red flags under the 5% concentration rule of thumb, while the 50-stock portfolio would not.[96] During volatile periods, concentrations of the trust corpus in individual stocks of more than about 3 percentage points over the firm’s share of the market as a whole[97] should usually be considered not diversified, triggering an explanation from the trustee.[98] If a trustee cannot always quickly shift the portfolio from active management to broad diversification as soon as idiosyncratic risk rises, this suggests the trustee should be more concerned about potential diversification costs even during calm periods than our results above would otherwise indicate.

The arguments above apply with equal force to trustees of defined benefit employee retirement plans under ERISA. These trustees are under a statutory duty to diversify, like the trustees of personal trusts under the UPIA and the Restatement.[99] For these ERISA fiduciaries, the duty of diversification should likewise be stricter during periods of upheaval when the value of diversification increases.[100]

To give a concrete sense of how our work can provide guidance for courts evaluating whether trustees have fulfilled their duty to diversify, consider a private trust that has invested all of the trust’s assets in a single stock.[101] Assume the trustee justifies the failure to diversify because selling the stock would trigger a capital gains tax realization. In this case, the alpha the trustee hopes to obtain is from the tax savings and is readily calculable. For simplicity, imagine the stock has a 0 tax basis, average idiosyncratic risk, and a single beneficiary with moderate risk aversion (with a CRRA coefficient of 2) during a relatively calm period. We calculated (in Table 1, supra) the benefit of diversifying would be equivalent to adding 6.3% to the return to the stock for the year. Ignoring the potential step-up basis at death,[102] triggering the tax this year rather than postponing it until next year would cost the trust:

α =

where τ is the tax rate and is the risk-free rate. The first part of this equation represents the lost time value of money in failing to delay recognizing the untaxed gains, while the second part represents the fact that investors only capture the after-tax portion of these gains. This expression represents the excess, alpha-like return the trust can expect from postponing realization. Even taking the risk-free rate as high as 5%, and if τ = 20% is the long-term capital gains rate, then the tax benefit to not diversifying is 0.8% of the value of the untaxed gain and it would be imprudent not to diversify. The alpha benefit from not diversifying (0.8%) is outweighed by the cost of failing to diversify (6.3%).

With a portfolio that is not as extremely under-diversified, the tax benefits might justify remaining undiversified. For example, if the trust instead held a portfolio of 10 stocks with 0 basis, whether it would be prudent to fully diversify might depend on the volatility of the market.[103] During volatile periods, the benefits of diversification increase, but the tax benefits are roughly fixed. Thus, during calm periods when the diversification benefits are only around 0.5%, it might be prudent to not fully diversify, thus saving the tax costs of 0.8%. During more volatile times, however, it would be imprudent not to diversify. For example, the average benefit of diversifying during 1999–2001 or 2008–2009 was 2.2%, well in excess of the 0.8% tax costs.[104]

Under other circumstances the gains from concentrating the trust portfolio may be harder to calculate, but it can still be important to estimate the costs of having a concentrated portfolio. For example, trusts are often used to perpetuate family businesses. In these businesses, the benefits of not diversifying are diffuse and difficult to quantify. These benefits include the potential for obtaining returns higher than the market, employment at the firm for family members, perquisites, family sentiment and pride of ownership, etc. Still the trustee can estimate the cost of failing to diversify—that is, the offsetting alpha required to make concentrating the trust assets in the family firm prudent—by using the average of small publicly traded firms in the same sector.[105] This provides a benchmark against which the benefits of control can be weighed. Moreover, these costs of not being diversified are likely to change significantly over time, with costs rising during volatile periods. Thus, all else equal, a prudent trustee will be more likely to seek or accede to a bid for the family firm in the midst of an unsettled market than in calm periods.[106] This is true even if the mean expected return for the firm was the same in both periods.

Frequently, the trustee is not only permitted to retain the concentrated position in a family firm but also required to do so by the settlor in the trust instrument. In such cases, the firm’s prospects or level of idiosyncratic risk may change in ways not anticipated by the settlor. Increases in risk may force the trustee to petition the court to allow her to sell the firm to avoid serious harm to the beneficiaries.[107] This is known as an “equitable deviation.” Our results demonstrate that courts should be most amenable to these petitions during periods when idiosyncratic risk is high. This is consistent with the most famous equitable deviation case, In re Pulitzer’s Estate.[108]

The Pulitzer case arose from the potential sale of the New York World newspaper during the throes of the Great Depression. In 1931, the trustees of Joseph Pulitzer’s testamentary trust petitioned the court to allow the sale of the New York World, which the trust was required to hold. At that time, the paper was foundering, and the early years of the Great Depression were a period of enormous market upheaval and spikes in idiosyncratic risk.[109] A moderately risk-averse person would have needed to receive a staggering 162% expected alpha to make her willing to hold only one of the publicly traded newspapers during the period, instead of a diversified portfolio of U.S. stocks, as compared with 19% from 1926 to September 1929.[110] Although the court did not use the language of risk, it wisely concluded that changed circumstances unforeseen by Pulitzer required the trustees to be allowed to sell the paper.[111]

Our results also militate toward the possible creation of a new duty, or at least best practice, for the drafter of the trust to warn settlors who are interested in setting up a trust that would depart from the diversified, low-fee, appropriate-risk benchmark about the offsetting alpha that would be required to justify that departure. Courts might even establish a cautionary “altering rule,” mandating that to be effective, a trust instrument opting out of the default duty to diversify must indicate that the settlor has been apprised of and understands the alpha tradeoff relevant to the investment restriction that the settlor wishes to put in place.

5. Subsidiary Duties: Prudent Exposure to Risky Assets.—The drafters of the UPIA recognized that no assets are categorically imprudent for all beneficiaries. This allows today’s trustees to avoid being forced to make beta mistakes by having too little exposure to equities, unlike the old constrained prudent man approach. The drafters also realized, however, that creating a portfolio with high systemic risk is usually imprudent for trusts meant for highly risk-averse beneficiaries, i.e., “widows and orphans” trusts.[112] Subpart III(C), infra, quantifies this intuition, showing that, unsurprisingly, the trustee should expect very large alphas before it would be prudent to invest the portfolio of highly risk-averse beneficiaries with full market exposure. A risk-averse investor who but-for the alpha opportunity would only rationally invest 10% of her portfolio in equities would need an offsetting annual alpha of 21.4% before investing in a well-diversified all-equity portfolio with a beta of 1.[113] Opportunities with so much alpha are, of course, rare. By contrast, relatively risk-tolerant individuals (CRRA = 1) would happily take very low exposure to risky assets if they could obtain alphas one-tenth that size.