A Negotiation Class: A New, Workable, and (Probably) Lawful Idea

Introduction

In their forthcoming article, The Negotiation Class: A Cooperative Approach to Class Actions Involving Large Stakeholders,[1] Professors Francis E. McGovern and William B. Rubenstein have created a new way to solve a major problem in a proceeding with a very large number of plaintiffs suing for money damages in a situation that can sensibly and fairly be resolved only by settlement. In those cases, the defendant is seeking as close to global peace as possible, but Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and due process require that each plaintiff be given an opportunity to opt out from any settlement. The problem for the defendant is that, if a settlement is reached, the plaintiffs with the strongest cases may opt out, resulting in the defendant paying too much for the weaker claims that settle, and still having to litigate the better ones. The authors’ solution, summarized below, solves that problem by moving the opt-out up front, so that it precedes the negotiation of the price for the class settlement. Therefore, the defendant will know before starting the negotiation process who is in and who is out of the class, hence the name “Negotiation Class.”

I agree that the negotiation class concept solves the adverse selection problem for the defendant and also strengthens the position of class counsel in negotiation. In addition, this solution solves another problem that I have seen in a number of class action settlements, most recently in the National Football League Concussion Case.[2] Before the opt-out takes place in a negotiation class, the class must agree on the formula by which the funds will be allocated if a settlement is reached with the defendant, and then the proposal must be approved by a supermajority vote of the class, as well by the court under Rule 23(e) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

For the reasons I explain in greater detail below, this process is much more likely to result in an allocation that is fair to all segments of the class with their differing interests. That is because class counsel needs as many class members as possible to remain in the class so that the defendant will be willing to negotiate over as close to a global settlement as possible. A negotiation class is unlike the typical settlement in which the allocation is done by class counsel after the deal with the defendant is struck, when absent class members have little leverage. By contrast, in the negotiation class, the allocation occurs first, when class members are not forced to choose between no deal and a bad deal. As a result, in order to reach agreement on an allocation formula, class counsel must consider the interests of all subgroups within the class (or realistically, their lawyers), even if they are not actually at the bargaining table. And class counsel must listen and take those views into account so that the class supports the allocation when the judge is asked to certify the class, so that large numbers of class members do not opt out, and so that the class as a whole votes to support the ultimate settlement if class counsel is able to reach an agreement with the defendant.

The authors of The Negotiation Class developed it while one (McGovern) was serving as a special master, and the other (Rubenstein) was a legal adviser to Judge Dan Polster, who is handling the multidistrict litigation (MDL) proceeding that has more than 2,500 opioid cases pending before him. Most of the cases were brought by counties, cities, and other units of local government that incurred massive expenses to pay the costs imposed by the opioid epidemic. Lead counsel for the plaintiffs in the MDL took up the authors’ idea and then implemented it in that proceeding. Judge Polster went along with most of what the plaintiffs proposed,[3] but in a decision handed down on September 24, 2020, a divided panel of the Sixth Circuit set aside the order approving certification of a negotiation class.[4] Because this Response is primarily intended as an analysis of the advisability of having negotiation classes, not their legality under current Rule 23, it will only respond briefly to some of the arguments that the Sixth Circuit majority accepted.

This Response proceeds in two parts. The first discusses the McGovern–Rubenstein proposal in greater detail, using as a hypothetical example, the claims of the fifty states, plus the District of Columbia, against the defendants in the opioid litigation. In the real case, the states all filed their own actions in state courts, with only state law claims, so that their cases cannot be removed. I use the states example because it is a simpler use of the concept of a negotiation class than the even more complicated class that Judge Polster approved. It also allows the basic legal and workability issues common to all potential negotiation classes to be explored without the complexity of the class that Judge Polster actually certified. In Part I, I also spell out the benefits that this process has for class members whose interests are not directly represented by lead or interim class counsel. I then compare it with the NFL Concussion Case where, I argue, the settlement was unfair to much of the class because the allocation decisions were arbitrary in many respects. I conclude that the overall balance struck by this new approach is both lawful and workable.

Part II assumes that negotiation classes are generally permitted and then examines the local governments’ class that was certified by Judge Polster. It explores the major specific objections made to the class by the appellants and the Sixth Circuit majority in the appeal, as well as some questions that I have identified on my own. I conclude that some of these objections are well-taken and that most could have been cured on remand if the class certification had been upheld.

I. The Negotiation Class—In Theory

The authors of The Negotiation Class divide the process into five steps.[5] Another way to look at it, and one that helps with parts of the legal analysis, is to consider it in two phases: prenegotiation and negotiation. In the first, the plaintiffs do not interact formally with the defendant. For simplicity, I assume only one defendant, but there is no reason why the idea will not work—and perhaps be even more useful—with multiple defendants. In this phase, all of the plaintiffs attempt to reach agreement on an allocation of whatever settlement is reached in phase two, they present the allocation to the court for class certification, and, if approved, class members are given an opportunity to opt out. In the workability aspects of this section, I will focus on the allocation step and will discuss the details of certification and opt-out when I turn to how this approach was carried out in the actual opioid litigation.

A. Phase One

1. Workability and Fairness to the Class

Let us assume that the proposed negotiation class is comprised of the fifty states plus the District of Columbia. The first step would be for all fifty-one members to meet, not to discuss how much they want the defendant to pay, but rather to focus on what is often the last question addressed by class counsel: How to divide up whatever settlement they can achieve. Obviously, at this point, they cannot allocate actual dollars but must instead derive a formula to be applied if the class and the defendant can agree on a total. In a few cases, the formula can be as simple as a pro rata share based on, for example, the amount of overcharge resulting from a price-fixing scheme or other unlawful conduct. However, in most cases, the allocation question will be more complex and, in many cases, not answerable by law, logic, or facts alone, but will end up being the product of multiple compromises.

Take the state opioid class example and simplify it by assuming that the applicable law is the same for all fifty-one class members. One allocation method would be to divide the prospective pie by fifty-one, but that is certain to be objectionable to much of the class because the harm suffered by different states would vary widely. Another would be to agree to allocate the money in proportion to each state’s damages provable to a special master, which would be unworkable because no one could be paid until all cases with damages were concluded.

Ideally, the class would seek out readily provable proxies that could be used directly via an allocation formula or at least be the basis for negotiating one. For example, population might be one input, on the theory that the opioid crisis was everywhere, or at least equally spread among the states. A second proxy might be the total of specific opioids sold in each state during the class period (presumably cabined by the statute of limitations on one end and, in this case, the unrealistic assumption that the epidemic is now over on the other). Or the states could use opioid-related deaths, Medicaid spending, or any number of other more or less objective factors to produce an allocation formula. In turn, that formula could take one of two basic approaches. One approach would spell out exactly what percentage each state will get, down to three decimal places. This would be the simplest approach to implement and clearest to all class members, but it would require detailed front-end calculations and agreements that may delay the process. A more complex formula would leave some of the fact-finding to a later date, but establish the allocation method, specifically which factors to take into account and what share of the allocation formula each factor would affect. In the actual case, the class chose three public-health-related factors for each class member—the number of opioid overdoses, the number of opioid deaths, and the number of opioid pills per capita—and created an algorithm that weighted them in an agreed upon manner.[6]

However the factors are chosen, the goal is to reach a formula that is both understandable to all class members and that is reasonably certain in its application.

Even attempting to illustrate how this process might work shows that there is no right answer to the allocation question and that compromise is the key element in the process. There are arguments for and against any of these (and many other) factors, but the class members know that unless they can reach agreement among themselves and have that agreement be sustained by the class’s vote at the end of the process (and approved by the court), there will be no settlement to divide. Moreover, in reaching this compromise, the class does not have to establish that certain facts would be provable or even admissible at a damages trial, but only that the class as a whole is willing to take them into account, along with other facts that other class members believe to be more relevant, as part of an agreed-on allocation formula. In other words, all the class’s interests must be represented in the allocation formula so that the class will vote to approve the deal at the end. As a practical matter, that requires all of the class’s various interest groups to be involved in the allocation bargaining process.

My strong support for the negotiation class concept is also based on a reason not discussed in McGovern and Rubenstein’s article: my experience in a number of cases in representing absent class members—those whose lawyers, if they have one, are not part of the class counsel team. The settlement process in a traditional settlement class focuses on maximizing the total dollars and assuring that the class members whose lawyers are on the leadership team are duly compensated, with little effort to assure that all potential class members fairly share in the settlement. My most recent example is the NFL Concussion Case, in which I was counsel for the amicus Public Citizen. Public Citizen objected to the settlement because class counsel reached a settlement that produced a system of payments that went to a very small percentage of the class, which I saw as a lack of adequate representation.[7] To be clear, the courts concluded that the settlement should be approved, and I do not seek to relitigate that case here, but only to show how differently it would have played out had the lawyers followed the negotiation class approach. But first, it is necessary to summarize the facts of that case as they would be relevant in a negotiation class situation.

Approximately 21,000 former NFL players sued for money damages for concussion-related injuries. According to paragraph 74 of the class complaint, studies and tests established that concussions resulted in early-onset of Alzheimer’s Disease, dementia, depression, deficits in cognitive functioning, reduced processing speed, attention and reasoning, loss of memory, sleeplessness, mood swings, personality changes, and the debilitating and latent disease known as Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (“CTE”).[8]

The class contended that the NFL was responsible for all of these injuries, but there were substantial factual and legal differences among their claims, such that no one asserted that a litigation class could be properly certified.

This case was not the first time that the NFL had been confronted with the question of whether to pay any claims that professional football caused dementia and traumatic brain injury in many former players. In 2007, the League had established the 88 Plan, which was the number of former all-pro tight end John Mackey. Mackey’s widow’s request to the NFL prompted it to start the program to provide limited funding for former players who suffered from the effect of brain injuries. According to class counsel, and there is no reason to doubt them, during the settlement discussions in the class action, the League stated that it was only willing to pay for those diseases under the 88 Plan because it had concluded that the science did not support payment for anything else.[9] The NFL agreed to pay not just those class members who had one of these four diseases at the time of settlement, but any class member who developed them in the future or for whom their initial diagnosis was of one disease but who later developed another more serious one.

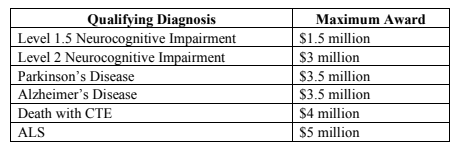

The settlement established a grid for what it called qualifying diagnosis, which provided for a maximum payment for each disease as follows:[10]

The problem for most of the class was that unless a player developed one of the diseases specifically defined in the settlement agreement, the player would receive no money, but would receive testing and some modest medical assistance in a short time period after the settlement was approved. Most significant for these purposes, class counsel’s own expert estimated that only 17% of the class would ever have a qualifying diagnosis, which meant that the rest would receive no monetary relief.[11] There was no dispute that many former players had serious cognitive and other health problems, but that in all likelihood, they would never develop a qualifying disease. Yet there were no additional subclasses or other representatives to speak up for those who did not have one of those diagnoses. In the end, Judge Layn Phillips (the court-appointed mediator) decided, and class counsel concluded, after reviewing the evidence regarding all the diseases alleged in the complaint, that it would be “fair” to compensate class members only for “early-onset dementia, Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and ALS.”[12]

Why did that happen? Class counsel did not set out to harm the 83% with no qualifying diagnosis, but those class members had no champion at the bargaining table, and each member of the class counsel team had individual clients who would benefit from the proposed settlement. Is there any wonder, especially in light of the NFL’s insistence on limiting compensation to the listed diagnoses, that class counsel did not demand that the money be spread more broadly?[13]

When the original settlement proposal was submitted to Judge Anita Brody, to whom the MDL was assigned, it was capped at $765 million. In that posture, despite the protestations of the NFL during the negotiating process about limiting the diseases for which there would be any compensation, there was no reason why it cared to which players the money was awarded and for what conditions. Nonetheless, class counsel never pushed back on the disease limitation or explained why it was fair to the class to confine the payments to those diseases. Judge Brody, without holding a hearing or receiving input from other class members, informed the parties eight days after the settlement was filed that the cap was unacceptable and would not be approved. The NFL subsequently agreed to remove the cap, and except for the addition of death by CTE noted above, nothing of substance was changed. With no cap, the NFL at least had a reason not to agree to compensate for other diseases or conditions. By contrast, in a negotiation class, the class members must create an allocation scheme among themselves up front because it is unlikely that a defendant will agree to an unlimited fund. Thus, the allocation issues will necessarily be resolved before the cap is negotiated, with all class members participating in that process, and thereby avoid a situation in which only a limited group of class members would be compensated.[14]

This 83–17 divide was the most significant intraclass conflict, but it was far from the only one. The settlement grid provided for maximum payments to the listed diseases, which ranged from $1 to $5 million. Where did those numbers come from? Surely not from prior settlements or judgments since there had been no prior concussion cases. They, of course, were nice round numbers to which class counsel and the NFL agreed. But those numbers were only the starting points from which two kinds of reductions were made. On the apparent theory that the number of years played in the NFL was correlated to each of these diseases (and identically for each), if a class member had played fewer than five seasons, which was true for an estimated 60% of the class, there was a 10% reduction in the award for each half-season fewer than five played.[15] In addition, because all of these diseases are also found in individuals who have never suffered concussions playing football, and are often the result of aging, there were further discounts for each five years beyond the age of forty-five at which the player was first diagnosed with the disease.

The necessity for any such adjustments, as well as the amounts and cut-offs for them, were not the products of law or any prior settlements, but simply what class counsel considered was fair to keep the total dollars within the negotiated cap. What is most interesting about these grid numbers and the adjustments is that they were entirely within the control of class counsel once the defendant had negotiated a cap. To be sure, neither the plaintiffs nor the NFL knew exactly how many valid claims there would be in each category and for each adjustment, but they both had reasonable estimates of those numbers. The fundamental problem was that the dollar figures on the grid were literally picked out of the air by class counsel with no input from the hundreds of other lawyers who had filed their own cases for other class members.

Despite these intraclass conflicts, which class counsel resolved by making all the allocation decisions themselves, Judge Brody and the court of appeals approved the settlement. It is not as though there were no objectors, but the principal objections came from class members who argued that the evidence strongly supported the conclusion that football concussions caused CTE and that the deal had to include CTE injuries as well.[16] There were many former players who had plausible CTE claims, and if this had been a negotiation class, their representatives would have been a meaningful part of the allocation process. In that posture, it is hard to imagine that they would have come away empty-handed because their subsequent vote would be needed at the second phase.

However, except for objections based on the failure to include CTE injuries on the grid, there were no significant objections from class members who were suffering from the many other serious conditions that the operative class complaint alleged were concussion-related injuries, but for which they would receive no compensation. This was not a case in which the absent class members were unrepresented: almost everyone in the MDL had a lawyer who had filed a complaint on his behalf. It is true, as class counsel had argued, that any class member who subsequently developed any of the diseases on the grid would be compensated, and perhaps their lawyers told them that for that reason, there was no basis to object. But there is another reason why most of those lawyers did not object: those lawyers also had clients who were on the grid, and if they objected to help one client, they were likely harming another. Put another way, the combination of the settlement grid and the conflicted status of the lawyers whose clients were left off the grid, created a structural conflict of interest that precluded the Rule 23(e) settlement process from working as it was envisioned.[17]

In its amicus briefs, Public Citizen (for whom I was co-counsel) argued that class counsel alone could not adequately represent all of the divergent interests. The class counsel in the NFL Concussion Case were doing what the Court in Amchem Products, Inc. v. Windsor[18] said that they could not properly do (and what the mediator in the case said they did): Play God and decide which class members got how much and on what basis. Class counsel correctly observed that the main problem in Amchem was that class members who developed diseases in the future were not represented. They avoided that here with a separate subclass for those who did not have a qualifying disease by providing that those class members who eventually developed one would be entitled to the same benefits as those who were ill at the time of the settlement.[19] In response to the charge that those who would receive nothing also needed representation, class counsel asserted that Public Citizen wanted to create multiple subclasses and that the bargaining process could not work with so many interests at the table, an argument that the court of appeals accepted.[20] Although the exact number of subclasses was never specifically discussed, it would have been somewhere between twelve and twenty, not perfect, but far more representative than the two subclasses of present and future injuries that class counsel created.[21]

An extreme irony on this score comes from the actual negotiating class in the opioid case. There are forty-nine class representatives from thirty states, each with its own lawyers, plus class counsel (including the chief lawyers from the cities of New York, San Francisco, and Chicago), as well as the lawyers in the other 1,300 filed cases, and perhaps some from the 34,458 local governments that will be part of the class.[22] Yet somehow they agreed to attempt to negotiate, and then successfully negotiated, an allocation formula that will bind the entire class and have to be approved by the votes of the class after the deal has been struck with the defendants. And who is the lead class counsel? Christopher Seeger, who was lead class counsel in the NFL case.[23] And is who is his lead appellate counsel? Samuel Issacharoff, who was lead appellate counsel in the NFL case.[24] These are the very lawyers who insisted that it would have been impossible to broaden the negotiating team in the NFL case, and they are just fine with an exponentially larger negotiating group in the opioid case.

Beyond irony, there is a real problem with the approach taken in the NFL Concussion Case: It implies that if a class encompasses so many interests that a classwide bargaining process is impossible, it is legitimate for class counsel to play God and make allocations based on what they alone think is fair to different groups within the class, all of whom are their clients. Of course, it is not. The beauty of the negotiation class process is that it has to solve this allocation problem in order to succeed. By giving the many splinter groups within the class a vote at the end, their interests must be accounted for in the allocation and the negotiation process leading to it. Put differently, class member democracy (the vote) replaces class counsel theocracy (the NFL counsel’s admitted approach).

For all these reasons, I whole-heartedly endorse the approach of the negotiation class in which as many relevant parties as possible come to the table at the outset and decide (or, more realistically, reach an acceptable compromise) on allocation issues before they begin negotiating over a single dollar amount with the defendant, all in the shadow of knowing that each class member will have a vote at the end. Not only is that system workable, but it is much fairer to all class members than having to argue about allocation once the dollar amount of the settlement has been reached. And if there is an actual agreement reached by class members on the allocation formula, there will be no need for any subclasses of the kind that allegedly would have prevented settlement in the NFL case.

2. Legality

But is a negotiation class lawful, which means, does reaching an allocation agreement, obtaining class certification for negotiation purposes, and providing a front-end opt-out, comply with Rule 23 and due process, both as a general matter and as applied? I defer the as-applied inquiry to Part II, where I examine the application of the negotiation class concept to the actual local governments class in opioids, but the issue of whether any negotiation class is ever permissible must be addressed on its own.

The contrary argument is very simple but unpersuasive. Rule 23 includes both litigation classes (the term does not actually appear, but the Rule was written with litigation in mind) and settlement classes, and it does not mention negotiation classes. According to this argument, because negotiation classes are not authorized, they are forbidden. The majority of the Sixth Circuit panel agreed with this argument, which is, in essence, that parties and courts may do only what is specifically authorized under Rule 23, and therefore negotiation classes are precluded.[25] The exhaustive dissent of Judge Moore reached the opposite conclusion, describing the majority’s approach as having “manacle[d] district courts” and “suffocate[d] the district court with textual piety,” whereas she concluded that the district court here properly “breathed life into a novel concept.”[26] The opening sentence in her concluding paragraph summed up her overall view of the issues presented: “We should not focus exclusively on the naked words of Rule 23 at the expense of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure’s equitable backdrop and in ignorance of the obvious precedent set by the settlement class’s creation and proliferation.”[27]

My vote is with Judge Moore mainly because, although settlement classes are expressly mentioned in Rule 23, that provision was not added until 2018, and the Court in Amchem in 1997 assumed that some settlement classes were permitted.[28] Ultimately, the Amchem Court found that the class there did not comply with other express limitations under Rule 23 and due process.[29]

There is another way to look at this first phase besides asking whether Rule 23 specifically authorizes negotiation classes. One could ask whether, in my states example, all the plaintiffs could jointly agree on an allocation formula before starting to negotiate with the defendant with no court involvement at that stage. I assume that such an agreement, made as part of an MDL litigation, would not run afoul of antitrust laws, and there is nothing in Rule 23 or any other Rule or statute that even arguably prohibits that approach.

If that is correct, the next question would be whether Rule 23 also precludes the states from asking the court to certify an agreed upon class, conditional on reaching an agreement with the defendant. The focus of this question on the appeal was on the one-time immediate opt-out after certification, but before any settlement with the defendant had been reached. A front-end opt-out is actually the norm under Rule 23 when certification of a litigation class is sought. In that situation, certification occurs “at an early practicable time” after the complaint is filed,[30] after which class members must be given the opportunity to exclude themselves from the class.[31] There seems to be no principled reason why that same opportunity cannot be applied to a class certified for negotiation only, with the possibility in both cases that the court may allow a new opportunity to opt out at the time of any settlement.[32] Indeed, the choice on whether to opt out will be a much more informed one in a negotiated class situation because the class members will know the allocation formula and know that they will have a right to vote on the back end. In addition, if they choose to opt out, they will still be a part of any litigation class that might be certified if the negotiation class fails to reach an agreement with the defendant.

In the opioid class appeal, class counsel argued that the defendants who opposed class certification have suffered no injury, and hence have no standing to appeal, but the majority disagreed.[33] Although defendants are correct that no order has been directed at them, they do have a real stake in assuring that the certification order cannot be challenged as outside of Rule 23. In particular, the whole theory behind a negotiating class is that the defendant will be more willing to bargain if it knows the precise size and composition of the class. That, in turn, requires that the front-end opt-out be valid because, if it is not, then the negotiation class has not solved the problem of back-end opt-outs. In that respect, the standing issue is like that in Phillips Petroleum Co. v Shutts,[34] in which the defendant objected to the nationwide class certified there. The class argued that the defendant had no standing to raise that objection, but the Court rejected that argument, finding that the defendant had a cognizable interest in assuring that it only paid the judgment against it if the class were properly certified so that no class member could sue it again on the same claim.[35] That reasoning applies here because of the opt-out order, and so the Sixth Circuit properly reached the validity of the negotiation class.

B. Phase Two—Legality

There are two elements in phase two: voting by the class and approval by the district court. The latter is no different from what takes place in a conventional settlement of a class action, except that it is also informed by, but not controlled by, the votes of the class. Those votes are likely to be a much better proxy than the number of objections or opt-outs, which should be recognized as of limited significance, unless there are very large numbers of either. And the court will, or at least should, be influenced by the favorable vote of those affected by the settlement if the issues are whether the payment from defendant is enough and whether the allocation is fair. There is always the possibility that the district court will see an affirmative vote and simply rubber stamp the settlement, doing no more than including the boilerplate language required by the Rule. But that can and sometimes does happen now, and there is no reason to think that an affirmative vote alone will result in any increase in the ill-advised approvals of settlements for negotiated classes.

The validity of a vote presents a different question. First, from a formal perspective, it is a different kind of check on unfair settlements than exists under Rule 23 now. But more to the point, the Bankruptcy Code contains express provisions for voting on business reorganizations under Chapter 11, including the express percentages required, and the vote is mandatory.[36] Moreover, the precise way that voting is to be conducted, as well as its role in the reorganization process, is spelled out in great detail by Congress, not by the plaintiffs in a particular negotiation class. Thus, because bankruptcy reorganizations can be reasonably analogized to class action settlements, one could argue that if voting is to be part of a class action approval process, it must be included in Rule 23 under the process by which the Rules are made, either by Congress or by the Supreme Court.[37] Under that approach, Rule 23 would have to set forth the circumstances in which a vote was required, as well as any supermajority requirements and whether any subgroups must separately approve the settlement.

Moreover, opponents would contend, the supermajority voting system in the opioid negotiation class, including the specific percentage chosen and the multiple ways that the votes will be counted, was simply agreed to by the class, unconstrained by Rule 23.[38] But in the future, a class could use a single vote by the entire class, with only a simple majority of those voting needed for approval. Because of the lack of any law controlling the voting system, opponents argue that the system is illegitimate.

I reject that formalistic approach, not because I believe that Rule 23 is controlled by its text (which does not preclude voting), but because that objection fails to recognize the limited and positive role that voting plays in assuring that any settlement of a negotiation class is fair to all parts of the class. First, because voting was agreed on by the class and approved at the front end, it is a necessary, but not sufficient, basis for approval of the settlement, which the court must still bless. The vote may not even be necessary: suppose that the deal with the defendant fails to obtain the necessary votes and class counsel decide to proceed, not as a previously certified negotiation class, but as a conventional settlement class. Counsel would have to file a new motion to have the (same) class certified as a settlement class, with a new opt-out right. Again, nothing in Rule 23 would prohibit that, even in the face of a negative vote.[39]

The most important reason why the inclusion of voting requirements does not invalidate the negotiation class approach is that the vote has no independent legal significance under the Rule or as a matter of due process. The court could still disapprove the settlement under Rule 23(e), even if 100% of the class supports it. What the vote does is give all class members an additional protection—largely by ensuring that their interests are considered in, and hence made a part of, the allocation mechanism up front—and provide the court with further evidence that the settlement is a reasonable one for all class members. Even if close to 25% of the class voted not to support a negotiated class settlement, that same percentage (or more) could also oppose a conventional class settlement, but that would not preclude the court from approving the settlement as in the best interests of the class.[40] If the vote is no more than an advisory recommendation, like an advisory jury under Rule 39(c) in a nonjury case, the inclusion of the vote does not affect the Rule 23 settlement approval process. Rather, it provides additional assurances to class members and the court that the proposed settlement is reasonable and fair to most, if not all, class members.

II. The Negotiation Class—In Practice

The parties to the appeal to the Sixth Circuit raised a number of objections, but because the majority concluded that Rule 23 prohibited negotiation classes, it did not discuss most of them. In my opinion, none of them would have provided an independent basis for overturning the district court’s certification order, but several of them are worth noting and should have been fixed on remand if the order had been upheld. I begin by discussing the objections raised by the appellants and then turn to my own questions about this certification.

A. Specific Objections Raised on Appeal

One objection to the approval order was that there was no class complaint to which it related,[41] although there were thousands of complaints, including short-form complaints that had been approved along the way. It is unclear why there was no class complaint, and there surely could be no doubt as to what claims the defendant would be opposing or being asked to settle. Nonetheless, the court should have insisted on class counsel filing a class complaint to resolve any doubts, and that could still have been done on remand so that any confusion by defendants or class members would be eliminated going forward.[42]

Related to the issue of the necessity for having a negotiated class complaint is whether the class has satisfied the Rule 23(b)(3) requirement that common questions must “predominate over any questions affecting only individual members.”[43] If this were a litigation class, even one for just the states, let alone for all the diverse local governments, no one would seriously argue that the predominance requirement had been met. The question is whether the fact that this class has been certified for negotiation only is enough to satisfy the predominance requirement. And on that question, Amchem arguably presents a significant barrier.

In Amchem, the Third Circuit overturned the order approving the settlement class there on a number of grounds, including because of its view that all of the requirements of Rule 23 applied to settlement as well as litigation classes.[44] The Supreme Court disagreed that settlement was always irrelevant, and it expressly concluded that the superiority requirement, which immediately follows predominance in Rule 23(b)(3), is lessened because any concerns about manageability are significantly diminished when there is a settlement.[45] Because the opinion did not include an express statement making settlement applicable to predominance, and because of other broad statements in Amchem about the applicability of Rule 23 generally and predominance in particular, there is an argument that a strict predominance requirement is applicable to all settlement classes, which would include, but not be limited to, negotiation classes.

On the other hand, fairly read, the opinion in Amchem rejected the settlement primarily because it failed the adequate representation requirement in Rule 23(a)(4) arising from the serious conflicts between those class members who suffered current injuries and those whose injuries would arise in the future, all of whom were represented by the same class counsel.[46] The Sixth Circuit majority did not have to decide whether the class failed for lack of predominance because it found that negotiation classes generally were not authorized by Rule 23. It did note the problem, which it suggested compounded the concept of a negotiation class, asserting the district court had “papered over the predominance inquiry.”[47] The dissent, by contrast, found that the district court properly found that the class met the predominance requirement of Rule 23.[48]

In the end, only the Supreme Court, either by a decision in an actual case or by an amendment to Rule 23, can resolve the question. This is not the place to survey what the courts of appeals have done with predominance in the many settlement classes they have upheld, but once again, the NFL Concussion Case, which the Supreme Court declined to hear, is relevant to the applicability of the predominance requirement to settlement classes.

The claims asserted against the NFL included negligence, fraudulent concealment, fraud, negligent misrepresentation, negligent hiring, negligent retention, wrongful death and survival, and civil conspiracy.[49] Because each claim was based on the state law applicable to each individual class member, there was no common legal issue. Moreover, there were certain to be factual challenges to the claim that the acts of the NFL caused each plaintiff’s injuries, and the actual damages suffered by each class member would be individual and not common. In short, if Amchem were read to require predominance to be met irrespective of settlement, the NFL settlement class certification could not have been upheld. But it was, and this is what the Third Circuit said on the related issue of commonality:

Even if players’ particular injuries are unique, their negligence and fraud claims still depend on the same common questions regarding the NFL’s conduct. For example, when did the NFL know about the risks of concussion? What did it do to protect players? Did the League conceal the risks of head injuries? These questions are common to the class and capable of classwide resolution.[50]

Further on, it specifically rejected the claim that predominance was not satisfied:

But Amchem itself warned that it does not mean that a mass tort case will never clear the hurdle of predominance. Id. at 625, 117 S. Ct. 2231. (“Even mass tort cases arising from a common cause or disaster may, depending upon the circumstances, satisfy the predominance requirement.”). Moreover, this class of retired NFL players does not present the same obstacles for predominance as the Amchem class of hundreds of thousands (maybe millions) of persons exposed to asbestos.[51]

One need not agree with the Third Circuit’s distinctions from Amchem that it made in the NFL Concussion Case to conclude that the lack of predominance (or commonality) is not a proper basis to set aside that class settlement or those that arise in negotiated classes. Indeed, the whole point of settlement in any mass torts class action—and in particular in negotiated classes—is to eliminate the questions that are not common to the class and to leave only the single issue on which the class is united: How much should the defendant pay? Although the Third Circuit covered all the subparts of Rule 23, the main focus of the appeals was on improper allocation of the settlement fund, which was a problem of inadequate representation that was also at the heart of the objection in Amchem.

The argument that predominance should not be a real problem in negotiated classes is illustrated by an alternative means of resolving cases like this that is not, as a practical matter, far from the facts of this case. Suppose that all the states entered a binding agreement in which each of them assigned to a single state (or other entity) the right to sue for the opioid claims set forth in their complaints. Suppose further that the agreement also provided that the net proceeds of any such claims will be divided in accordance with a specific agreed-on formula. If there were no class, Rule 23 would not apply, and no other law would prohibit such an agreement from being implemented.[52]

That is, in essence, what is happening with opioid claims, and it explains why predominance should not be a barrier to settlement under a negotiation class. Predominance is intended to protect both the court and the defendants from having to try a case under the belief that a settlement down the road will dispose of all the litigation, only then to find that the trial is only a very small first step. Under that rationale, the negotiation class is no different from a hypothetical agreement among all the class members and should present no predominance issue. For that reason, the predominance requirement, reasonably interpreted, should not be a barrier, because the agreement on allocation and the limitation of the class certification to a negotiated settlement for the class as a whole have eliminated all questions except the common one: How much is the defendant willing to pay to resolve the claims in the class complaint?

Judge Polster’s certification order concluded that the commonality requirement of Rule 23(a) was met because many (but not all) of the complaints filed in the MDL had a RICO count and that those claims predominate.[53] He also found common issues relating to whether the defendants violated the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), although he recognized that there is no private right of action under that law.[54] However, all of the complaints also have state law claims, including those for nuisance, and those laws vary widely from state to state.[55] Again, if certification were sought as a litigation class for all claims, and one state’s law did not govern the defendant’s behavior nationwide, it would plainly fail on commonality grounds, under cases like Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes.[56] But if, as shown above, predominance is not a concern in negotiation and other settlement classes, then neither is commonality, which is an easier requirement to satisfy than is predominance.

There is, however, one question arising from the court’s inclusion of only the RICO claim as its basis for its finding of commonality. Did the court limit the authority to settle to only the RICO claims, or may the parties settle all claims (as asserted in the many individual complaints and would be in a class complaint) so that defendants can obtain “global peace”? The final paragraph of the court’s opinion clarifies the matter by authorizing class counsel to negotiate, with all defendants on all claims, which makes it hard to understand why the prior parts of the opinion were limited to RICO claims.[57]

The Six Cities appellants who are class members also objected to the fact that class counsel postponed the question of how any money that goes to counties will be further distributed to cities or other subunits of government under those counties.[58] If a county has absolute control over its constituent parts, then there is no problem because the county will dictate the answer. But those cities that have filed their own lawsuits—including the three major cities whose lawyers are part of the class counsel team—presumably believe that they are entitled to recover their damages irrespective of what their counties recover. I doubt that this is a basis to deny certifications, but that does not mean it might not have been a potential problem in this case, especially given the very large number of governmental units in the class and the fact that their relationships to one another are matters of state law. It is true, as class counsel argue, and Judge Poster seemed to agree,[59] that not every detail need be resolved before class certification. Moreover, this hardly seems like the kind of issue that is incapable of resolution down the road, but it might have been easier to resolve, and to do so more fairly, sooner rather than later.

The Six Cities appellants also raised a variety of objections falling under the general category of conflict of interests mainly relating to the ability of class counsel to fairly represent the entire class, which the majority did not discuss and which the dissent rejected.[60] Another alleged conflict was that some class members were said to be more interested in using the negotiation process to make changes in how opioids are marketed in the future rather than recovering for past losses because the laws of those localities are less favorable than those of other class members.[61] In one sense, a conflict between those who prefer a focus on future remedies, in contrast to compensation for past damages, frequently arises in Rule 23(b)(3) class actions, but the theoretical problem becomes a legal problem only when the conflict results in significant segments of the class being harmed by the reality of the conflicts. I do not downplay the possibility that such conflicts may make some settlements impossible, but that is a question for Phase Two when a specific settlement is before the court and not as a basis for concluding that the concept of a negotiation class is unlawful or unworkable. Moreover, the requirement of the supermajority votes decreases the likelihood that real conflicts will develop, and surely the possibility of nonspecific conflicts should not be enough to overturn negotiated class certification at this stage.

B. Additional Questions

The current appeal only dealt with what I have called Phase One. After the district court approved the proposal, class members had sixty days to decide whether to opt out. For those who filed an objection, they had to choose between taking an appeal or opting out. Given how early in the process this was, there was no reason to require a class member to making a binding choice, at least until the appeal had been resolved, especially in this case where there was a legitimate (now realized) challenge to a new approach to class settlements. Accordingly, if the certification order had been upheld, the district court should have exercised its authority under Rule 23(e)(4) to allow those who appealed a second chance to opt out.[62] In future cases, the approval order should routinely provide that, if there is an interlocutory appeal, there will be a second sixty-day period after an affirmance becomes final, in which any class member who has opted out may come back into the class, and anyone who has joined an appeal may opt out within that same time frame. That additional opt-out is unlikely to affect the size of the class to any significant degree, and any uncertainty about the class size will surely be resolved before serious discussions with the defendant are concluded.[63]

The McGovern–Rubenstein proposal does not spell out how class counsel and class representatives should proceed in trying to achieve consensus on the allocation and voting issues. In the traditional class action, most class members have claims that are too small to warrant hiring an attorney. That was not the case in the NFL Concussion case, and it is surely not true in the opioid litigation, where there are 1,300 cases on file, although there are thousands of small counties and towns in the class that have not sued and do not have representation in the lawsuit. That does not mean that class counsel should meet with the lawyers for every city and county that has sued, let alone the representatives of the remainder of the estimated local government class of more than 34,000. But if consensus is the goal, and if one way to achieve that is to learn what suggestions or objections potential class members have, then efforts at a significant outreach as part of the discussion on allocation and voting would be in order, regardless of the precise requirements for upfront supervision of preliminary approvals and class notices as envisioned by the 2018 additions to Rule 23(e)(1) and (2). In addition, the statutory requirement to notify state attorneys general of class settlements[64] may not apply until there is an actual settlement proposal on the table, but it surely makes sense to give them notice of the possibility of a negotiation class. For both the state attorneys general and other class members, their early involvement may slow down the process a little at this stage, but it should help in the end. And if there are fatal flaws or even limited objections, it is better for all to have them surface when changes can be made before countless hours are wasted.

The two key elements in a negotiation class are the allocation formula and the voting rules. In reading the opinion approving the plan and the accompanying order, there were references to both, but the court did not detail the specifics of either, let alone were they explained in a way that an appellate court could use to decide whether to uphold them. However, the methods of allocation and voting are spelled out in reasonable detail in the report of the Special Master Cathy Yanni, who made specific recommendations as to both matters as part of the certification process.[65] Judge Polster adopted them in Part IV of his opinion on certification,[66] sensibly concluding that, even though the implementation of both formulas will not occur until there is an actual settlement, if there were obvious problems with either, this was the time to fix them.[67]

Even more important, the notice to the class and the FAQs were also less than complete in this regard. If class counsel (and defendants) in future negotiation class cases wish to be sure that there are no legitimate reasons for the court to allow a second opt-out once the deal has been struck, it is vital that the notice to the class, which is the basis on which class members decide whether to remain in the class or not, contains both the allocation formula and the voting methods in as much detail as reasonably possible. And to the extent that such descriptions appear to be vague, that may suggest that there is more work to be done before the notice and opt-out period can take place.[68]

Conclusion

If the Sixth Circuit’s ruling becomes the final word on the current legality of negotiation classes, that should not be the final word on the subject. Judge Moore’s dissent is not simply a rejection of the majority’s understanding of Rule 23, but more significantly, is an endorsement of the concept of a negotiation class and of the real-world benefits that it brings to the resolution of complex cases like opioids, with which I concur. Nothing in the majority’s opinion would prevent the Supreme Court, working through its rulemaking process, from amending Rule 23 to make the idea a reality.

Perhaps more significantly, if that process goes forward, in contrast to other bold ideas, this one will have had a test drive in the opioid cases, and at least some of its potential problems will have already surfaced, enabling a clearer and more defect-free amendment to be approved. It is no surprise that there were some bumps in the road, given the size and complexity of the class and the legal and factual issues in the MDL proceeding. In some ways, it is surprising that there were not more. Fortunately, the implementation problems that surfaced do not go to the heart of the negotiation class concept, and most can be readily cured without undermining the benefits of the basic concept. That in itself is quite a triumph.

- .Francis E. McGovern & William B. Rubenstein, The Negotiation Class: A Cooperative Approach to Class Actions Involving Large Stakeholders, 99 Texas L. Rev. 73 (2020). ↑

- .In re Nat’l Football League Players’ Concussion Injury Litig. (NFL Concussion Case), 821 F.3d 410 (3d Cir. 2016), cert. denied, 137 S.Ct. 591 (2016). ↑

- .In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 332 F.R.D. 532, 536 (N.D. Ohio 2019). ↑

- .In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 976 F.3d 664, 667 (6th Cir. 2020). Class counsel have filed a petition for rehearing en banc, which is currently pending before the 6th Circuit. ↑

- .McGovern & Rubenstein, supra note 1, at 79. ↑

- .See Report of Special Master Cathy Yanni at 5, In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 332 F.R.D. 532 (N.D. Ohio 2019) (No. 17-md-02804), ECF No. 2579. ↑

- .NFL Concussion Case, 821 F.3d 410, 432 n.9 (3d Cir. 2016). ↑

- .Joint Appendix Vol. III at 882, NFL Concussion Case, 821 F.3d 410 (3d Cir. 2016) (No. 2:14-cv-0029-AB). ↑

- .Joint Appendix Vol. XII at 3575–76, NFL Concussion Case, 821 F.3d 410 (3d Cir. 2016) (No. 2:14-cv-0029-AB). ↑

- .NFL Concussion Case, 821 F.3d at 424. At the urging of the district court, the NFL also agreed to make payments of $4 million for death with CTE, provided the player died before final approval of the settlement on April 22, 2015. Id. at 423–24. ↑

- .Joint Appendix Vol. IV at 1568, NFL Concussion Case, 821 F.3d 410 (3d Cir. 2016) (No. 2:14-cv-0029-AB). ↑

- .Joint Appendix Vol. XII at 3807, NFL Concussion Case, 821 F.3d 410 (3d Cir. 2016) (No. 2:14-cv-0029-AB). ↑

- .There is no debate that the two individuals who were designated as class representatives did not have any meaningful role in the actual bargaining, and so the entire burden of assuring adequate representation law was on class counsel. ↑

- .As for the notion that the NFL would never allow the payment to more than the listed diseases, this is what its lead counsel said at the fairness hearing: “What has been lost in the fog of the objections is that the league chose to do the right thing here” by agreeing to a substantial monetary settlement. Joint Appendix Vol. XV at 5389, NFL Concussion Case, 821 F.3d 410 (3d Cir. 2016) (No. 2:14-cv-0029-AB). There is no reason to think it impossible that, when all sides were motivated to reach a fair settlement, fair representation of the interests at stake would produce a settlement that benefited more of the class. ↑

- .Joint Appendix Vol. III, supra note 11, at 997. ↑

- .NFL Concussion Case, 821 F.3d 410, 421–22, 430, 433, 441–44 (3d Cir. 2016); In re Nat’l Football League Players’ Concussion Injury Litig. (NFL Concussion Case), 307 F.R.D. 351, 396–403 (E.D. Pa. 2015). ↑

- .This may also be one of the reasons why there were so few opt-outs. ↑

- .521 U.S. 591 (1997). ↑

- .NFL Concussion Case, 307 F.R.D. at 376. ↑

- .NFL Concussion Case, 821 F.3d at 432 n.9 (“We agree with the District Court that additional subclasses were unnecessary and risked slowing or even halting the settlement negotiations.”). ↑

- .In some respects, reaching agreement in a negotiation class is similar to doing so among a large and diverse group of creditors, including tort claimants, in a bankruptcy reorganization proceeding under Chapter 11. See, e.g., In re Dow Corning Corp., 280 F.3d 648 (6th Cir. 2002). ↑

- .In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 976 F.3d 664, 667 (6th Cir. 2020). ↑

- .Jeff Overley, Lead Attys Approved For Opioid MDL ‘Negotiation Class’, Seiger Weiss LLP (Aug. 19, 2019, 8:29 PM), https://www.seegerweiss.com/news/lead-attys-approved-for-opioid-mdl-negotiation-class/ [https://perma.cc/8TFK-S3S2]; Christopher A. Seeger Named Plaintiffs’ Co-Lead Counsel In Multidistrict NFL Concussion Litigation, Seeger Weiss LLP (May 15, 2012), https://www.seegerweiss.com/news/christopher_a_seeger_named_plaintiffs_co-lead_counsel_in_multidistrict_nfl_concussion_litigation/ [https://perma.cc/GFD3-BFMG]. ↑

- .Paul Anderson, The Future of the NFL Concussion Settlement, NFL Concussion Litig. (Nov. 15, 2015), https://nflconcussionlitigation.com/?p=1799 [https://perma.cc/E3SD-94DF]; Nate Raymond, Case to Watch: Opioid Plaintiffs to Defend Novel ‘Negotiating Class’ on Appeal, Reuters (July 24, 2020, 3:13 PM), https://www.reuters.com/article/health-opioids/case-to-watch-opioid-plaintiffs-to-defend-novel-negotiating-class-on-appeal-idUSL2N2EV1SL [https://perma.cc/6WDL-48WN]. ↑

- .In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 976 F.3d at 672–74. ↑

- .Id. at 677 (Moore, J., dissenting). The remainder of her analysis of this basic issue is at 677–80. Her dissent ran almost forty-two pages in print and the majority was only seventeen. ↑

- .Id. at 708 (Moore, J., dissenting). ↑

- . The dissent concluded that settlement classes were first recognized in the Rules in 2003, not 2018, but also recognized that nothing turns on which is the correct date. Id. at 684 n.18 (Moore, J., dissenting). ↑

- . Amchem Prods., Inc. v. Windsor, 521 U.S. 591, 615, 625 (1997). ↑

- .Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 (c)(1)(A). ↑

- .Id. at 23(c)(2)(B)(v). ↑

- .Id. at 23(e)(4). ↑

- . In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 976 F.3d at 670. The dissent disagreed with that conclusion because it found, as I do, that the reasons provided by defendants and the majority were unpersuasive. Id. at 704–07 (Moore, J., dissenting). Neither opinion confronted the argument for standing based on the defendants’ need to know whether the opt-out provision is valid (as I argue in the text). ↑

- .485 U.S. 797, 803–04 (1985). ↑

- .Id. at 805. ↑

- .11 U.S.C. § 1126(c) (2018). ↑

- .28 U.S.C. § 2072 (2018). ↑

- .Report of Special Master Cathy Yanni, supra note 6, at 10. ↑

- .Because the negotiation class is not based on a Rule or statute, there is nothing that requires a vote at all, let alone a 75% supermajority. Because the court must still approve the settlement, it is possible that future negotiation classes may neither have a voting component, nor one that is only simple majority. These possibilities suggest that, at an appropriate time, Rule 23 should be amended to formalize what constitutes a supermajority, if one is to be required. ↑

- .With an estimated 83% of class members in the NFL Concussion Case expected to receive no financial benefits, a properly informed class might well have voted to reject the entire settlement, and almost surely would have garnered an opposition exceeding 25%. Yet even after such a negative vote, Rule 23(e) would not have forbidden the court from approving that settlement. ↑

- .Brief of Appellants at 31–32, In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 976 F.3d 664 (6th Cir. 2020) (No. 19-4097). ↑

- .In the NFL Concussion Case, a class complaint was filed only when the settlement was submitted for approval, and no one suggested that the timing of the filing was problematic. Defendants in the opioid case also argued that the district court had not made a “rigorous” examination of the class claims and that there were factual disputes. The lack of specificity for both (and the apparent failure to raise the factual-basis argument below) persuaded me that those objections were unlikely to derail the certification order or were the kind of objection that would make the negotiation class unlawful or unworkable in the future, which is my major interest. The majority did not address the issue, and the dissent indirectly rejected it by acknowledging the need for a “rigorous” analysis and then finding no fault with what the district court did. In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 976 F.3d 664, 686 (6th Cir. 2020). ↑

- .Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(3). ↑

- .Amchem Prods., Inc. v. Windsor, 521 U.S. 591, 609 (1997). ↑

- .Id. at 619–20. ↑

- .Id. at 625–28. ↑

- .In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 976 F.3d at 675. ↑

- .Id. at 687–91 (Moore, J., dissenting). ↑

- .NFL Concussion Case, 821 F.3d 410, 422 (3d Cir. 2016). ↑

- .Id. at 427. ↑

- .Id. at 434. ↑

- .As discussed in the Baker article, supra note 15, at 1169, counsel would still have to comply with the applicable ethical rules in making the allocations. ↑

- .In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 332 F.R.D. 532, 548–50 (N.D. Ohio 2019). ↑

- .Id. at 550–51. ↑

- .See id. at 544 (referencing state law claims). ↑

- .564 U.S. 338 (2011). ↑

- .In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 332 F.R.D. at 556 (authorizing negotiation “on any of the claims or issues identified here, or those arising out of a common factual predicate.”). The court also certified issues relating to the CSA, which is even more baffling, because issue certification orders made under Rule 23(c)(4) are needed for litigation, not settlement purposes. The Sixth Circuit majority criticized the district court for attempting to certify an issue class, In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 976 F.3d 664, 675 (6th Cir. 2020), but the dissent was untroubled by the inclusion of an issue class. Id. at 685–91 (Moore, J., dissenting). ↑

- .Brief for Appellants at 9, In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 976 F.3d 664 (6th Cir. 2020) (No. 19-4099). ↑

- .In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 332 F.R.D. at 553. He also made another observation, which is in some tension with his flexibility conclusion: “The allocation and voting plans are therefore fixed – class members will make opt-out decisions based on them – and they will not change if a settlement is reached.” Id. at 552. However, like all agreements, this allocation formula will inevitably be subject to interpretation, which to some class members may seem like a change. Moreover, if the need for clarifications or amendments is recognized down the road to assure that the settlement can be efficiently and fairly carried out, class counsel should not be precluded from making them. It is possible that a specific change might trigger a further opt-out if a class member could show a significant adverse impact from the change. Similar problems might occur with the voting rules, and they too should be subject to minor amendments or adjustments if necessary. ↑

- .In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 976 F.3d at 692–95 (Moore, J., dissenting). ↑

- .Id. at 696–97 (Moore, J., dissenting). Like the other alleged conflicts, the majority did not discuss it, and the dissent rejected it. ↑

- .The additional opt-out in Rule 23(e)(4) literally applies when a settlement is presented to the court. However, there is no reason why courts should not be able to allow a second opt out at other times. For the converse cases, where class members who opted out have a change of heart, there is rarely an objection to allowing them to come back in. ↑

- .I would also allow a second opt out to other class members who were not appellants, so as not to put a premium on a class member filing a separate appeal or joining an appeal of another. This suggestion is not central to the main opt out point. ↑

- .28 U.S.C. § 1715. ↑

- .Report of Special Master Cathy Yanni, supra note 6, at 10. ↑

- .In re Nat’l Prescription Opiate Litig., 332 F.R.D. 532, 553–54 (N.D. Ohio 2019). ↑

- .As part of the voting formula, there are two subclasses and hence two subgroups for voting. The reason for this division is that only those class members who filed suit before June 14, 2019—the date that the motion to certify was filed—are eligible to seek attorneys’ fees for their counsel who can show contributions to the settlement. However, in all other respects, the two groups use the same allocation formula to determine the amount of their recovery. ↑

- .As discussed in the Baker article, supra note 15, at 1169, counsel would still have to comply with the applicable ethical rules in making the allocations, even though this is a class action, not an inventory settlement. ↑