A Functional Analysis of SIFI Insolvency

In a 1989 article that remains one of the clearest, most sensible explications of an especially tricky point of bankruptcy law, Jay Westbrook announced a forthright methodology: “I call my approach ‘functional,’ because it proceeds by working through the problem from first principles.”[1] The same basic technique can tell us a lot about how banks—and other bank-like creatures or SIFIs,[2] to use the industry lingo—should fail.

Since the disgrace of Lehman, the question of how to handle failing SIFIs has been quite vexed.[3] On the one hand, governmental rescue of shareholders and other investors is beyond annoying, and there is some intuitive sense that if management does a poor job, they and their investor backers should face the consequences just like any other firm.[4] That bank managers would have the temerity to pay themselves large bonuses shortly after a taxpayer rescue only emphasizes the point.[5]

On the other hand, there is a widespread understanding that a large bank, or a sufficiently interconnected one, is not quite like Kmart, Enron, or even American Airlines, in that when the bank fails, it tends to take a large chunk of the economy along with it.[6] Pre-failure regulation can mitigate some of the effects,[7] but by the time we get to insolvency—or “financial distress,” if we want to acknowledge that here we are talking as much about liquidity as balance sheets[8]—the regulatory string has pretty much played out.[9] And in the end, we have trouble deciding if we really mean to treat large financial institutions like normal failed firms.[10]

Thus, the 2010 legislative response to Lehman, and AIG, and Bank of America, and Citibank, and every other large financial institution that almost failed (or did, in the case of Lehman) was notably wobbly on the question of “how will a big bank fail?” Dodd-Frank created a new, FDIC-focused “orderly liquidation authority” (OLA) to handle these cases but then made it incredibly difficult to actually use OLA.[11] Instead, banks are told to plan for failure under the Bankruptcy Code, and this time they should not expect any of the help that Lehman got.[12]

When, if ever, the new system will be used is left uncertain, particularly given that the ability to invoke the process is left in the hands of a politically appointed Treasury Secretary after consultation with the President.[13] In past administrations we might have assumed that, when push came to shove, the Secretary would do the right thing. Present-day developments might leave us a bit more circumspect on this point.[14]

Ultimately, after nearly a decade of waffling between “special” and “normal” bankruptcy for banks, I believe we are now ready to build upon what we have learned and to take the necessary further step: stop feigning that bank insolvency can or should happen in bankruptcy court.

I reach this conclusion through application of Professor Westbrook’s functional analysis. Namely, we need to consider what it is that we are trying to achieve in a bank-insolvency case and how that compares with bankruptcy law in general. Bank insolvency, I submit, is all about special priorities: both ordinal and temporal. The Bankruptcy Code, on the other hand, takes an “equality is equity” approach to priorities as a baseline, mostly using state law to draw the claim–asset border.[15] Bargaining for results within the general “equality” framework is another key feature of traditional insolvency law.[16]

Financial institution insolvency law expressly rejects this model; it instead is all about protecting some favored group from the effects of insolvency.[17] There is no equality here, and it was never intended that there would be equality.[18] And thus it is time to stop pretending SIFI insolvency is “normal” corporate insolvency—it is bigger.

I. The Problem

Large American financial institutions are typically made up of a holding company and several additional key pieces.[19] Each piece of the financial institution, including the holding company, is subject to a different regulatory and insolvency regime.[20]

For example, in a June 2017 report to the Federal Reserve and the FDIC, JPMorgan Chase & Co. noted that it is “supervised by multiple regulators.”[21] The Report describes the domestic front as follows:

- The Federal Reserve acts as an umbrella regulator . . . .

- The firm’s national bank subsidiaries, JPMCB and CUSA, are subject to supervision and regulation by the OCC and, with respect to certain matters, by the Federal Reserve and the FDIC.

- Nonbank subsidiaries, such as JPMS LLC, are subject to supervision and regulation by the SEC and, with respect to certain futures-related and swaps-related activities, by the CFTC.

- The firm conducts securities underwriting, dealing[,] and brokerage activities in the United States through JPMS LLC and other broker–dealer subsidiaries, all of which are subject to SEC regulations, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority[,] and the New York Stock Exchange, among others.

- Certain of the firm’s subsidiaries are registered with, and subject to oversight by, the SEC as investment advisers.

- In the United States, one subsidiary is registered as a futures commission merchant, and other subsidiaries are either registered with the CFTC as commodity pool operators and commodity trading advisors or exempt from such registration. These CFTC-registered subsidiaries are also members of the National Futures Association.

- JPMCB, J.P. Morgan Securities LLC, J.P. Morgan Securities, PLC[,] and J.P. Morgan Ventures Energy Corporation have registered with the CFTC as swap dealers.

- The firm’s commodities business is also subject to regulation by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, London Metals Exchange[,] and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.[22]

Other large American financial institutions would also be subject to insurance regulators, typically at the state level. Most, of course, are also subject to foreign regulation.[23]

There are historical reasons for this fragmentation, mostly tied to the tendency to develop American financial law in times of crisis, beginning with the Civil War, with new laws being added piecemeal to address then-recent events.[24] As with most American legislation, particularly at the federal level, there has never been a single reform law enacted to consolidate the whole. The result is that both pre-failure regulation and post-failure “resolution” of a large financial institution is typically achieved piece by piece, with one regulator taking an arm while another takes a leg. As discussed below, Dodd-Frank only partially improves on this situation.

A. The Fundamentals of Financial Institution Insolvency

A prototypical large American financial institution or SIFI is comprised of four basic regulated pieces: a holding company, one or more depository banks, a broker–dealer, and insurance companies.[25] Interspersed between is the “dark matter” of global banks: unregulated subsidiaries. These allow banks to do financy stuff outside the regulatory architecture of the core parts of the bank, although in theory they remain subject to the umbrella regulation of the Federal Reserve.[26]

In a world before Dodd-Frank, or in a world where OLA is not invoked, the holding company is subject to the normal Bankruptcy Code process, presumably chapter 11.[27] While the Federal Reserve has regulatory powers over the holding company under the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956,[28] that Act contains no insolvency provisions.[29] Thus, we fall back on the business insolvency system of general applicability. Recent examples have included the notorious September 15, 2008, chapter 11 filing of Lehman Brothers Holdings, Inc. and the chapter 11 filing of Washington Mutual’s parent company.[30]

Most depository banks are insured by the FDIC.[31] Whenever the Comptroller of the Currency appoints a receiver for an insured national bank, the Comptroller must appoint the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation receiver.[32] As the exclusive statutory receiver of any insolvent insured national bank, the FDIC cannot be removed as receiver, and the courts have no ability to interfere with the process.[33] Likewise, even under the old pre-New Deal rules, and those still applicable to uninsured national banks (mostly trust companies), the Comptroller has the ability to appoint the receiver without ever going to court.[34]

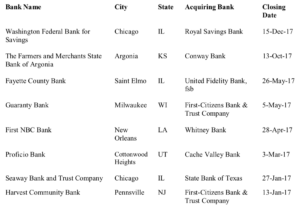

Recent examples of the modern FDIC approach include the aforementioned Washington Mutual primary operating subsidiary and the banks shown on the table, which includes all the FDIC receiverships in 2017.[35] Note the inevitable resolution of these banks by transferring the deposits to a healthy institution;[36] the FDIC pursued a similar strategy with Washington Mutual, where Chase took over its branches and deposits.[37]

The law provides that SIPC or the SEC may file an application for a protective decree with a federal district court if SIPC determines that any member has failed or is in danger of failing to meet obligations to customers and meets one of four worrisome conditions.[41] Upon filing, the case is quickly referred to the bankruptcy court.[42] The powers of the trustee in a SIPA case are essentially the same as those vested in a chapter 7 trustee appointed under the Bankruptcy Code, but the SIPA trustee operates with somewhat less judicial oversight.[43] Before the case even gets underway before the court, customers will have their accounts transferred to a healthy broker.[44]Normally broker–dealers are handled under SIPA—the Securities Investor Protection Act. SIPA created SIPC—the Securities Investor Protection Corporation—a quasi-private company that oversees an insurance fund for customers.[38] Although SIPC is an independent body, the SEC has oversight power over its bylaws and rules and may compel SIPC to promulgate regulations to effectuate the purposes of SIPA.[39] The insurance in this case, unlike the more familiar FDIC deposit insurance, protects only against securities or cash that are missing at the point of insolvency; there is no guarantee of value.[40]

While the holding company is in chapter 11, the depository bank is handled by the FDIC, the broker–dealer is liquidated by a SIPA trustee, and the insurance companies will be subject to state court receiverships under the oversight of the state insurance commissioner.[45] Insurance companies, no matter what size, are regulated by the states, and thus their insolvencies are also a question of state law.[46]

The basic structure of insurance failure is fairly uniform across the states: the insurance regulator goes to court and gets a receiver appointed, often the regulator itself,[47] to take control of the insurance company.[48] State guaranty funds, set up and paid for by solvent insurance companies operating within the jurisdiction, pay covered policyholder claims up to certain limits, which are often rather low.[49]

And then the unregulated bits of a big financial institution bring us back to chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code. At least the holding company and the “extra” bits of the financial institution end up in the same process; the other pieces are in a variety of forums—some in courts, some not.

B. Dodd-Frank’s OLA Solution

Recognizing that this overall system was somewhat less than ideal, the drafters of Dodd-Frank created a new super bankruptcy system, OLA. But OLA only partially solves the problem of an integrated financial institution being pulled apart by regulatory (and insolvency) balkanization.[50] And it does nothing to address the issue of cross-border SIFIs, which is rather important, considering that every SIFI is, almost by definition, a cross-border SIFI.[51]

First, Dodd-Frank’s drafters had no stomach for a fight with state insurance regulators, and thus insurance company insolvency remains outside the new order.[52] Broker–dealers are swept up in the process, but in an opaque way: the OLA receiver can take whatever assets it wants, leaving the residue behind. And the entire process is extremely difficult to commence and operates only as a backstop to the normal rules.[53]

In particular, to invoke OLA, the FDIC needs the agreement of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors (by a two-thirds majority) and the Treasury Secretary, who is required to consult with the President.[54] If the SIFI in question is more broker–dealer than depository bank—Goldman Sachs might be an example here—the SEC takes over the FDIC’s role in initiation, but the FDIC will, nonetheless, become the receiver if the process goes forward.[55] The statute expressly provides that the regulators must consider the effect of default on financial stability, on low income, minority, or underserved communities, and on creditors, shareholders, and counterparties.[56]

The Treasury Secretary is separately charged with evaluating the use of OLA under a two-part test.[57] First, the Secretary looks at whether the SIFI is in default or in danger of default.[58] A bank is in default when it is likely to file for bankruptcy, has incurred debts that will deplete all or most of its capital, has more debts than assets, or will likely be unable to pay its debts in the normal course of business.[59] In essence, a bank is insolvent if it is insolvent under any reasonable definition of the term.

Second, the Secretary must evaluate the systemic risk involved in the potential default of the SIFI in question.[60] The Secretary also must find that “no viable private sector alternative is available to prevent the default of the financial company.”[61]

If the SIFI clears these hurdles, the company’s board is presented with a choice: consent (and be exculpated from any potential liability to shareholders) or we, the regulators, will go to court.[62] Presumably, the board consents in most cases, and the FDIC is appointed as a receiver for the company.

As a receiver, the FDIC takes on the duties of transferring or selling assets, creating bridge financial organizations that can help assume assets or liabilities during the liquidation process, and approving valid claims against the company that will need to be paid.[63] The Orderly Liquidation Fund acts as a government-run DIP loan[64] throughout the process.[65] The Treasury lends the FDIC money to resolve the institution.[66] If there is a net cost, the FDIC then recoups the money spent by imposing a fee on surviving large, complex financial institutions.[67]

OLA provides a set of basic rules for all proceedings.[68] All action under OLA must be taken to preserve the financial stability of the economy as a whole, not merely to preserve the specific company in question.[69] Shareholders cannot receive payment until all other claims are paid—that is, the normal priority rules apply.[70] Management “responsible” for the SIFI’s failure must be “removed.”[71] Presumably, that means they must be fired—and not banished, or transported to Australia, or something like that. The FDIC is also prohibited from providing equity financing to the SIFI, which makes sense, given that other parts of Title II also call for liquidation of the defaulting SIFI.[72]

C. SPOE and “Chapter 14”

Because the application of OLA to an entire financial institution would appear to be unwieldly and would not cover the international aspects of the corporate group, a new approach was needed.[73] Single point of entry (SPOE) was that new strategy.

The SPOE idea benefits from a simple elegance: insolvency should only involve the holding company and no other part of the institution.[74] All problems would be solved at the holding-company level by having the holding company take on the burdens of financing the entire operation.[75] Other subsidiaries might interact with the outside world as part of their normal trading operations—the swaps subsidiary would continue to engage in trading, for example—but the holding company would be in charge of all general finance.[76]

Thus, if the financial institution were to encounter financial distress, its equity interests in its subsidiaries would quickly move to a new “bridge bank,” while its bondholders would look to the equity of that new holding company for their recovery.[77] Shareholders in the old institution—“to use an expression more forcible and familiar than elegant”[78]—would be wiped out. At the same time, the subsidiaries would benefit from forgiveness of their liabilities to the parent company, providing a source of relief for strained balance sheets.

SPOE itself addresses the problems of using OLA, but there remains the issue of Dodd-Frank’s stated preference for normal bankruptcy procedures. To meet this challenge, a variety of parties have come forth with proposals to amend the Bankruptcy Code to facilitate a SPOE-style bankruptcy proceeding.[79] Lumped under the general heading of “chapter 14,” after one of the early Hoover Institute proposals,[80] these plans would allow a quick holding-company-only bankruptcy case for a financial institution. In some cases, the new chapter 14 would replace OLA entirely, while in others it would simply make the Bankruptcy Code a more attractive alternative to OLA.[81]

Most of the recent versions of chapter 14 have been designed to use SPOE within a procedure that at least resembles chapter 11. The debtor holding company would file a petition and would initiate a near immediate 363 sale of its assets to a buyer–trust.[82] The debtor would then move toward confirmation of a liquidating plan that would distribute interests in the trust as payment to creditors.[83]

Chapter 14 thus tethers the Bankruptcy Code to the SPOE approach to bank resolution. The vital question then is whether SPOE will work, or, more aptly, whether it will work most of the time.[84] Undoubtedly, there is something odd about fixing a shortcoming in a financial institution through the holding company when the holding company itself is probably the least likely place for such a flaw to develop.[85] Almost like doing a root canal by way of orthoscopic surgery on the knee—it could work, but it seems terribly indirect.

And the notion that all the operating subsidiaries throughout the world will continue business as usual in the days after the parent company has failed assumes a high degree of rationality in the midst of financial collapse. It is almost as if the proponents of SPOE have already forgotten what happened in 2008. At the very least, they assume that the presence of Dodd-Frank will provide the assurance and calm that was rather obviously lacking before.

And while US regulators seem to be in favor of SPOE for domestic SIFIs, they seem quite happy to force “multiple points of entry” on international banks operating in the United States through mechanisms such as the Fed’s foreign bank (intermediate) holding company rules.[86] This has the predictable effect of undermining resolution planning at the international level as regulators jockey for position in anticipation of the next Lehman Brothers Europe.[87]

Overall, SPOE has something of the character of a parlor trick or one of those 1980s law review articles that suggested that chapter 11 could be replaced with a few simple contracts. One is left with the nagging feeling that it’s all a bit too crafty to actually work outside the parlor or the slide deck.

D. The Fundamental Problem

Chapter 14, SPOE, and OLA contain a stated preference for the Bankruptcy Code that papers over the reality that this country does not typically address bank insolvency under the Code. Rather, a receiver, appointed by a regulator, runs the show when a bank fails.

And while broker–dealers, insurance companies, and SIFIs more generally may not be “banks” in the narrow, legalistic sense, they are banks in the economic sense.[88] They take in funds with the promise of liquidity and invest those funds in longer-term assets, like loans, mortgage-backed securities, and the like.[89] And “when short-term debt funds longer-term liabilities, a defining characteristic of banks and much of the shadow banking system, the institutions that result are inherently fragile.”[90]

The fundamental problem, then, is what to make of the conflicting approach to bank insolvency. I address that issue in the next part of this Paper and argue that at heart this represents a confusion of bank insolvency and bankruptcy.

II. Functional Analysis

“Whenever an area of law has become conceptually and doctrinally confused, it is always helpful to return to first principles.”[91] With regard to bank or SIFI failure, such a return to core principles is long overdue.

“Equality of distribution among creditors is a central policy of the Bankruptcy Code. According to that policy, creditors of equal priority should receive pro rata shares of the debtor’s property.”[92] That is, traditional business bankruptcy is focused on questions of creditor rank and equality within ranks.[93]

Rank questions have both temporal and ordinal components. For a variety of practical reasons, some creditors get paid before others.[94] And negotiations over a chapter 11 plan hinge on who gets paid what within those classes that have yet to be paid when it comes time to formulate a plan.[95] What counts as a “claim” and what counts as an “asset” for purposes of bankruptcy is determined by reference to underlying state law, sometimes with a federal Bankruptcy Code overlay.

While the Code provides the framework of rank, the precise treatment of creditors within those ranks is a matter of negotiation. In a traditional chapter 11 case, this negotiation results in a reorganization plan that provides an outline of the reorganized debtor.[96] The plan can radically alter the debtor’s management, its ownership, its tax profile, its relationship with employees and future claimants, and perhaps even the type of business the debtor performs.[97] In place of a reorganization plan, the debtor might file a liquidation plan or a plan containing features of both.

Consider a recent example. Teen-apparel specialty chain rue21, Inc. emerged from bankruptcy on September 22, 2017.[98] Under the confirmed plan, prepetition holders of the $538.5 million term loan received about two-thirds of the equity in the reorganized company.[99] Holders of the $250 million 9.0% senior unsecured notes due in 2021, and all other unsecured claims, received a 4% equity stake.[100] The remainder of the new equity went to a DIP lender.[101]

In all cases, the distribution of the new equity was the product of negotiation between the various creditor groups, each trying to get as much as possible. Those negotiations happen within the equality framework established by the Bankruptcy Code.[102]

That stands in direct contrast to financial institution insolvency, where the key decisions about who gets what have already been made before the case commences.[103] In particular, financial institution insolvency mechanisms decide in advance that certain favored creditors will receive priority at the expense of the remaining creditors. Indeed, what happens after those favored creditors are taken out of the insolvency process is typically of lesser concern.

We see this most directly in broker–dealer liquidations where customers are made whole—through a segregated fund of customer property and a gap-filling insurance scheme—before any other creditor is even considered.[104] To the same effect are insurance receiverships, where policyholders are expressly elevated under the law of every state to an elite status that precedes all others.

Depository banks operate under a similar regime, through a combination of deposit insurance and, more recently, a federal depositor preference statute. More practically, the frequent use of purchase and assumption—or “P and A”—transactions, where depositors are transferred over to an acquiring bank, represents an even more obvious means of excluding a special class from an insolvency process.[105]

The “safe harbors” in the Bankruptcy Code provide a similar status for repo and derivatives trades, excepting them from all of the key provisions of the Bankruptcy Code.[106] To be sure, the safe harbors are far sloppier in providing their priority—in that they extend far beyond what is needed to protect the financial institutions engaged in these trades.[107] But whatever we think about the merits, they represent a policy decision by Congress to ditch the normal insolvency rules in favor of a system in which a certain preferred group prevails over the default rule of creditor equality.[108]

What, then, are the first principles of business insolvency at play here? At heart, business bankruptcy, and most of business insolvency, is aimed at recognizing a standard set of creditor priorities and ensuring creditor equality within those priorities. Creditors are urged to bargain for their specific treatment.

Bank insolvency, on the other hand, is about advancing legislatively defined policy goals that have been set in advance of insolvency.[109] We may disagree about the wisdom of certain of those goals, but they are set through a legislative process and not within the framework of creditor bargaining so familiar to bankruptcy attorneys.[110]

On the surface, bank insolvency thus looks like normal insolvency, but it is really quite different.[111] The next part of this Paper, thus, looks at the implications of that conclusion for one key aspect of insolvency law: the role of bankruptcy courts.

III. The Problem of Courts

In one of their myriad attempts to replace Dodd-Frank’s OLA with a new chapter of the Bankruptcy Code, House Republicans argued that:

[T]he bankruptcy process is administered through the judicial system, by impartial bankruptcy judges charged by the Constitution to guarantee due process in public proceedings under well-settled rules and procedures. It is a process that is faithful to this country’s belief in the Rule of Law.[112]

It is hard to quarrel with the rule of law, capitalized or not. Nonetheless, I use this part of the paper to explain why courts are an uneasy fit in the case of a SIFI insolvency.

As a starting point, “corporate bankruptcy scholars tend to characterize bankruptcy as an extension of the private transactional realm, with judges external to that world.”[113] This conception of business bankruptcy, although clearly overstated and even wrong, presents a problem for efforts to apply the “normal rules” to SIFI insolvency. In short, given the broad public effects and regulatory considerations tied to a SIFI’s failure, the notion that a system of private bargaining could or should address the matter is nonsensical.[114]

Financial institutions create debt instruments that are something more than debt, and indeed become valuable social products.[115] More broadly,

financial markets are integral to the production of commercial goods, public goods, and social services. Many businesses and individuals regularly rely upon financial institutions to provide short-term loans when the individual or business experiences temporary cash management difficulties.[116]

In addition, financial institutions play key roles in the creation of money.[117] About 70% of the U.S. money supply is in the form of deposits.[118] For deposits to perform this function—and more broadly for banks to function as the institutional backbone of the payment system—depositors need to be reasonably confident that: (1) there will not be a significant delay in transferring or withdrawing deposited funds (illiquidity) and (2) these funds will not be written down or converted into equity in the context of any bankruptcy proceeding (loss of value).[119]

All would tend to argue against some sort of closed insolvency system where the public interest is shut out in favor of bilateral or even multiparty private negotiation.

And indeed the entire notion of systemic importance undermines the basis for private bargaining.[120] That the failure of a SIFI affects not only the bank itself or its investors, but also other companies and individuals, inherently takes it out of the realm of private bargain and into a more general, public sphere.[121]

Turning to a more sensible conception of corporate bankruptcy, we have to acknowledge that modern bankruptcy courts play an active role in moving the case to confirmation of a plan.[122] Thus, chapter 11 is a multifaceted competition between various stakeholder groups and the debtor, with the court pushing the entire thing forward within a framework that we shorthand by reference to the “pari passu principle.”[123]

A full theoretical conception of judging within chapter 11 is beyond the scope of this Paper. But the aim here is to contrast any reasonable conception of chapter 11 with the aims of financial institution insolvency. In short, we have to consider chapter 11, a multiparty negotiation conducted within the structure of creditor equality, with the policy aims of bank insolvency, broadly defined. A bankruptcy proceeding:

is a specialized process for dispute resolution in connection with firms and individuals in financial or economic distress, but it is hardly narrow, technical, or specialized in substance. Bankruptcy cases frequently raise a broad range of legal issues beyond the intricacies of bankruptcy-specific doctrine. They routinely implicate non-bankruptcy-specific rules of decision and have done so throughout the modern history of federal bankruptcy law. Both as a matter of doctrine and theory, bankruptcy law aims to honor to the greatest extent possible the parties’ non-bankruptcy entitlements. Typically, state common law or statutory rights make up those non-bankruptcy entitlements, and bankruptcy courts therefore must decide matters that require application of non-bankruptcy-specific common law or statutory provisions.[124]

In contrast, financial institution insolvency advances the policy goals of the legislature and financial regulators. Specifically, it advances the policy of regulators—including the legislature—at the point of financial distress.[125] Its primary aim is not adjudicatory, but rather regulatory.

The fact that bank insolvency has specific policy aims itself suggests an immediate point of difference with chapter 11. Whereas normal corporate insolvency provides a framework for negotiation, SIFI insolvency aims to preordain the outcome of the process.

A bankruptcy judge is an uneasy fit in such a process, inasmuch as the judge is left with little to do when the key decisions have all been made in advance by statute or regulation. An example is seen in OLA itself, where the court’s sole role is to determine whether the Treasury Secretary’s determination on two points—“that the covered financial company is in default or in danger of default and satisfies the definition of a financial company under § 5381(a)(11)”—was arbitrary and capricious.[126] After that the court is essentially told to “go away.”[127]

The still-pending Financial CHOICE Act, a sweeping chapter 14-style bill that the House passed in June 2017,[128] follows a more extreme path. Although it purportedly replaces OLA with normal bankruptcy procedures, one of the first things to happen in a bank bankruptcy under the Act is the removal of all of the debtor’s assets from the bankruptcy estate.[129] Essentially, the bankruptcy court is left to sort out a fight over the residue, while the bulk of the action happens off stage.

Indeed, after the initial transfer, everything will apparently be resolved under state trust law, presumably New York State’s law. The bill provides that “[a]fter a transfer to the special trustee under this section, the special trustee shall be subject only to applicable nonbankruptcy law, and the actions and conduct of the special trustee shall no longer be subject to approval by the [bankruptcy] court in the case under this subchapter.”[130]

The CHOICE Act provides that the trust:

shall be a newly formed trust governed by a trust agreement approved by the court as in the best interests of the estate, and shall exist for the sole purpose of holding and administering, and shall be permitted to dispose of, the equity securities of the bridge company in accordance with the trust agreement.[131]

Thus, the bankruptcy court has some fleeting power before approval of the trust, but that must be exercised under extreme time limits—perhaps as little as one day.[132]

The terms of the trust are only subject to a few vague rules, and the pronouncement that “the trustee shall confirm to the court that the [Federal Reserve] Board has been consulted regarding the identity of the proposed special trustee and advise the court of the results of such consultation.”[133] The latter leaves open at least the theoretical possibility that a trustee could be appointed in the face of Fed objections—so long as the bankruptcy court is willing to sign the order.

The only other express role for regulators is a requirement that the trustee consult with the FDIC and the Fed before selling the shares of the debtor, and, again, the trustee must disclose the results of those discussions to the bankruptcy court.[134] The court, however, has no actual power over the trustee at this point.

Thus, an elected New York Supreme Court judge and (perhaps) the state attorney general will exercise some loose oversight over the process, but otherwise, the assets will largely disappear from the public eye. If that looks too menacing to management, the trust could be formed under the law of some other jurisdiction—indeed, there appears to be no express requirement that the trust be formed under domestic law. Thus, the bankruptcy court might have twenty-four hours to approve a trust governed by Manx law, to take one possible example.

The trust might even avoid application of the Bank Holding Company Act if it were established with a term of less than twenty-five years.[135] The underlying holding company that the trust owns would be subject to regulation, but the trust has the potential to be entirely opaque. This from legislation that is sold as increasing transparency.

In short, while a modern chapter 11 case features “hands on” judicial involvement, and that is a key feature of chapter 11 as practiced, such a role is inconsistent with the policy goals of a financial institution insolvency case. The CHOICE Act, the most prominent of the recent chapter 14 proposals, is at best a pretend bankruptcy case for financial institutions.

IV. Facing Facts

At a broad level, the global financial system is designed to fail.[136] The very structure of SIFIs and the nature of the explicit and implicit governmental backstops baked into the system will always encourage banks to take ever-larger risks.[137] But this is inextricably linked to my earlier observation that banks supply social goods; as a nation, we like money and credit, but using the same institutions to provide both presents us with some important and awkward policy trade-offs.

Regulators inevitably find it impossible to keep up, since bankers will always beat them in resources and influence.[138] Nevertheless, because we worry about a world without big banks, and what it would look like, we tolerate this death-defying condition.[139]

In this context, the insolvency system for SIFIs matters quite a bit.[140] A bank near insolvency must not be allowed to operate, since shareholders have nothing left to lose from taking ever riskier bets, and have every incentive to leave taxpayers “holding the bag.” The credibility of the threat to take the SIFI away from its owners—the shareholders and managers—and run it in the public interest is vital if this downward spiral is to be avoided.

One fundamental aspect of a credible SIFI insolvency system is that, upon activation, the outlines of “what will happen” are both clear and credible.[141] One part of that certainty traditionally comes from the complete protection of certain favored classes of creditors—that is, in bank insolvency, priority dominates over equality.

Another aspect of the clarity that SIFI resolution requires is an understanding at the outset of the process of how the resolution case will proceed.[142] Bank, broker–dealer, and insurance company resolutions all follow formally distinct insolvency models in this country, yet any such entity works through its insolvency with similar goals. For example, when a broker–dealer fails, customer accounts are moved to a healthy broker, any gap in customer assets is made up by SIPC, and the typical customer ceases to concern itself with the insolvency process.[143] Stockbrokers from the local Main Street broker to Lehman Brothers have followed this model.

Chapter 11 offers no similar certainty at inception. First, the parties might dispute and litigate the question of what “equality” looks like in any particular chapter 11 case. Next, the precise form of the reorganization plan is up for grabs in every case. Plans in one case are often modeled on what “worked” in a prior case, but the precise contours of the plan are largely unknown at the commencement of the case.

This uncertainty does not work in the context of financial institution insolvency.[144] And thus, banks are resolved without court involvement, and broker–dealers and insurance companies are resolved with court involvement only in the later stages of the process, when the issue becomes reconciling claims more than stabilizing the institution. These are fundamentally different processes from chapter 11.[145]

OLA tries to hide this reality by providing a thin veneer of judicial oversight at the outset of the case before quickly dispensing with the judge.[146] The CHOICE Act is in many respects even more disingenuous in that it pretends to be a normal bankruptcy process.[147] But the court loses control over the debtor’s assets at the outset of the case, and the public agencies—the FDIC and the Fed—are not granted any meaningful participation in the process. Even the regulatory status of the post-transfer trust—which clearly should be considered “a financial holding company” under the Bank Holding Company Act, but might evade even that basic regulation—is left rather vague under the proposed Act.

The CHOICE Act pretends to be a bankruptcy case pretending to be a bank insolvency case, while being neither. Instead, it puts the bulk of the control in the hands of a private trustee who has broad control over the SIFI’s assets with limited oversight. That trustee might be subject to only a state attorney general’s normal power over trusts.

The entire chapter 14 project is based on this same basic misunderstanding of the goals of bankruptcy, as contrasted with the goals of SIFI resolution.[148] In theory, a SIFI could be resolved in a bankruptcy process, but policymakers have generally believed that the societal costs would be too high. And indeed, if we think back to the pre-FDIC bank receiverships—where depositors were mere unsecured creditors[149]—that supposition is likely correct.

Chapter 14 advocates point to the transparency of chapter 11 as a virtue to be lauded over normal bank insolvency procedures.[150] The latter, in their view, are too apt to become mechanisms of bailout and favoritism, whereas chapter 11 looks like a more virtuous market system. The question is whether realizing due process “up front”—as opposed to after the fact, in the form of a lawsuit against the FDIC or other regulators—really works in conjunction with the policy goals that motivate bank-resolution mechanisms.

Arguably, the CHOICE Act itself tells us that the answer to this question is “no,” since the actual in-court part of the process is so slight under the proposed law. If that is the best that the advocates of “bankruptcy for banks” can do, we might suspect that true bankruptcy will never actually work.

Conclusion

Bank insolvency uses much of the language of “normal” insolvency. But bank resolution is not the same as chapter 11 or any other business insolvency process. Bank insolvency is about special priorities, whereas corporate bankruptcy is about creditor equality and bargaining. Too often, we let the similar language confound the analysis.

In an idealized world, bank insolvency is a purely technical project with fixed distributional consequences. In reality, particularly when the insolvency has systemic consequences, it takes on a political dimension as well. That is, while certain policy choices are made ex ante, through the choice of resolution mechanism, other policy choices will have to be made ex post, when failure actually happens.

All of the “super chapter 11” or “chapter 11 for banks” proposals—including the actually enacted OLA—attempt to put a judicial gloss on the policy and political process that is bank insolvency. Some, like the CHOICE Act, appear aimed at moving policy choices away from regulators by pretending to give power to judges, while actually moving policy choices to private actors.[151]

It is thought that this judicial veneer will provide a kind of legitimacy to bank insolvency that proponents believe was lacking in the rescue efforts in 2008. But, if taken seriously, the judicial role is entirely incompatible with efforts to contain a systemic crisis. Moreover, the veneer is quite apt to crack in any event: consider the broad role played by the U.S. and Canadian governments in the automotive bankruptcy cases, which involved at best marginally systemic debtors.[152] Somewhat confusingly, many of the critics of those cases nonetheless support some form of chapter 14.

If we do not take the judicial role in bankruptcy for banks seriously and see it as instead a smokescreen, the conclusions are even more disturbing. At best, the CHOICE Act—and proposals like it—are little more than disguised power grabs by insiders designed to use rule of law concerns as a cover for a deregulatory agenda. When an actual systemic crisis comes, it seems inevitable that the need for governmental assistance will arise yet again, and we will be right back where we were in 2008.[153]

My goal has been to draw attention to the confused thinking involved in many current approaches to bank insolvency. Bank and business insolvency use similar language to describe fundamentally different mechanisms. Only by a return to first principles can we reach sensible policy analysis.

- .Jay Lawrence Westbrook, A Functional Analysis of Executory Contracts, 74 Minn. L. Rev. 227, 230 (1989). In a recent article, Professor Westbrook abandoned the phrase “Functional Analysis” in favor of the alternative “Modern Contract Analysis,” but I take that change to be limited to the specific context of § 365 of the Bankruptcy Code. Jay Lawrence Westbrook & Kelsi Stayart White, The Demystification of Contracts in Bankruptcy, 91 Am. Bankr. L.J. 481, 484 n.16 (2017). ↑

- .Systemically Important Financial Institutions. ↑

- .Kathryn Judge, The First Year: The Role of a Modern Lender of Last Resort, 116 Colum. L. Rev. 843, 849 (2016). ↑

- .See Arthur E. Wilmarth, Jr., Turning a Blind Eye: Why Washington Keeps Giving In to Wall Street, 81 U. Cin. L. Rev. 1283, 1379–81 (2013) (noting that major banks have entered relatively modest settlements with the SEC without admitting liability—a practice that one judge criticized as “half-baked justice at best” because it fails to impose sanctions on specific individuals). ↑

- .Saule T. Omarova, Wall Street as Community of Fate: Toward Financial Industry Self-Regulation, 159 U. Pa. L. Rev. 411, 415 (2011). ↑

- .Kathryn Judge, Interbank Discipline, 60 UCLA L. Rev. 1262, 1272 (2013); see also Henry T.C. Hu, Swaps, the Modern Process of Financial Innovation and the Vulnerability of a Regulatory Paradigm, 138 U. Pa. L. Rev. 333, 367–70 (1989) (contending that there is widespread belief that the collapse of a financial institution “could cause the money supply to drop unexpectedly, thereby causing unemployment to rise and output to fall”). ↑

- .See Martin Wolf, Banking Remains Far Too Undercapitalised for Comfort, Fin. Times, Sept. 21, 2017, at 9 (“Banking remains less safe than it could reasonably be. That is a deliberate decision.”). ↑

- .See Adam J. Levitin, In Defense of Bailouts, 99 Geo. L.J. 435, 455–56 (2011) (explaining how a “domino effect” can exist among financial firms, expanding financial distress beyond insolvency and into liquidity). ↑

- .See Peter Conti-Brown, Elective Shareholder Liability, 64 Stan. L. Rev. 409, 419 (2012) (highlighting the fact that Dodd-Frank is a preventative regulatory measure that seeks to prevent financial crises and taxpayer-funded bailouts). ↑

- .Anat R. Admati, Financial Regulation Reform: Politics, Implementation, and Alternatives, 18 N.C. Banking Inst. 71, 74–75 (2013). ↑

- .See David A. Skeel, Jr. & Thomas H. Jackson, Transaction Consistency and the New Finance in Bankruptcy, 112 Colum. L. Rev. 152, 196 (2012) (explaining that the trigger for using the OLA is “more complex—calling for U.S. Treasury initiation with the concurrence of the Federal Reserve and FDIC . . .”). ↑

- .Stephen J. Lubben, Transaction Simplicity, 112 Colum. L. Rev. Sidebar 194, 203 (2012). ↑

- .12 U.S.C. § 5383(b) (2012). ↑

- .Cf. Barry Schwartz, George Washington and the Whig Conception of Heroic Leadership, 48 Am. Soc. Rev. 18, 26 (1983). Schwartz observes:At a time when most Americans take for granted their government’s ability to outlive its unscrupulous leaders and protect individual liberties, it is difficult to appreciate the whiggish obsession about abuse of power, or to take seriously the conviction that government stands or falls on the virtues of its leaders.Id. ↑

- .See, e.g., Westbrook, supra note 1, at 252 (characterizing the principle that “all creditors be treated equally” as the “most universal of all insolvency principles throughout the world”). For more on the stated goals of chapter 11, see Sarah Pei Woo, Regulatory Bankruptcy: How Bank Regulation Causes Fire Sales, 99 Geo. L.J. 1615, 1621–22 (2011). ↑

- .Thomas S. Green, Comment, An Analysis of the Advantages of Non-Market Based Approaches for Determining Chapter 11 Cramdown Rates: A Legal and Financial Perspective, 46 Seton Hall L. Rev. 1151, 1155 (2016). ↑

- .See Daniel R. Fischel et al., The Regulation of Banks and Bank Holding Companies, 73 Va. L. Rev. 301, 318 (1987) (“The primary difference is that the thrust of bankruptcy laws is to ensure that creditors of the same class are treated equally, whereas federal deposit insurance ensures that certain classes of creditors are paid in full.”). The authors of the foregoing argue that “the economic functions of bankruptcy laws and federal deposit insurance are very similar.” Id. In this Paper, I argue otherwise. ↑

- .In an earlier era, the bank and bankruptcy systems may have had similar goals, but that was before the advent of deposit insurance and the general move away from creditor equality in the financial context. See Davis v. Elmira Sav. Bank, 161 U.S. 275, 284 (1896) (“[O]ne of the objects of the national bank system was to secure, in the event of insolvency, a just and equal distribution of the assets of national banks among all unsecured creditors, and to prevent such banks from creating preferences in contemplation of insolvency.”). ↑

- .This part of the paper draws heavily on my forthcoming book: Stephen J. Lubben, The Law of Failure: A Tour Through the Wilds of American Business Insolvency Law (forthcoming 2018). ↑

- .See John C. Coffee, Jr. & Hillary A. Sale, Redesigning the SEC: Does the Treasury Have a Better Idea?, 95 Va. L. Rev. 707, 719–20 (2009) (describing the United States’ unique approach to regulation: three different agencies oversee banks, while another agency oversees securities and yet another oversees futures); Patricia A. McCoy et al., Systemic Risk Through Securitization: The Result of Deregulation and Regulatory Failure, 41 Conn. L. Rev. 1327, 1343 (2009). ↑

- .JPMorgan Chase & Co., Resolution Plan Public Filing 134 (2017). ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .JPMorgan Chase specifically mentions regulators in England, Japan, and Hong Kong. Id. ↑

- .See Mark J. Roe, Some Differences in Corporate Structure in Germany, Japan, and the United States, 102 Yale L.J. 1927, 1948–49 (1993) (introducing the development of American banking regulation); Arthur E. Wilmarth, Jr., The Transformation of the U.S. Financial Services Industry, 1975–2000: Competition, Consolidation, and Increased Risks, 2002 U. Ill. L. Rev. 215, 225–27, 313–14 (2002) (summarizing the restructuring of the banking industry, including the passage of the FDICIA in 1991 in response to banking failures); see also Kenneth E. Scott, The Dual Banking System: A Model of Competition in Regulation, 30 Stan. L. Rev. 1, 9 (1977) (stating that “the national banking system was created during the Civil War”); Edward L. Symons, Jr., The “Business of Banking” in Historical Perspective, 51 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 676, 698–99 (1983) (discussing the National Bank Act). ↑

- .Howell E. Jackson, The Expanding Obligations of Financial Holding Companies, 107 Harv. L. Rev. 507, 509 (1994). ↑

- .Michael S. Barr, The Financial Crisis and the Path of Reform, 29 Yale J. on Reg. 91, 99 (2012). ↑

- .See Cassandra Jones Havard, Reconciling the Dormant Conflict: Crafting a Banking Exception to the Fraudulent Conveyance Provision of the Bankruptcy Code for Bank Holding Company Asset Transfers, 75 Denv. U. L. Rev. 81, 81–82, 89–92 (1997) (clarifying that the “Bankruptcy Code . . . governs the insolvency proceedings of the bank holding company” and providing examples of holding companies filing under chapter 11). ↑

- .12 U.S.C. § 1841 (2012). ↑

- .Cf. Henry N. Butler & Jonathan R. Macey, The Myth of Competition in the Dual Banking System, 73 Cornell L. Rev. 677, 697–98 (1988) (noting that “[t]he Bank Holding Company Act regulates the activities of any company that controls a bank” without mention of insolvency proceedings). ↑

- .See Diane Lourdes Dick, The Chapter 11 Efficiency Fallacy, 2013 BYU L. Rev. 759, 790 (2013) (describing the Washington Mutual bankruptcy); see also Stephen J. Lubben & Sarah Pei Woo, Reconceptualizing Lehman, 49 Tex. Int’l L.J. 297, 303 (2014) (describing the Lehman bankruptcy). ↑

- .Key exceptions include certain financial technology companies (at this point, more potential than real) and trust companies, both of which might operate under a national bank charter without deposit insurance. See, e.g., 12 U.S.C. § 27(a) (2012) (outlining when the comptroller may authorize an association to commence banking). ↑

- .12 U.S.C. § 1821(c)(2)(A)(ii) (2012); see also Edward H. Klees, How Safe Are Institutional Assets in a Custodial Bank’s Insolvency?, 68 Bus. Law. 103, 108–09 (2012) (explaining that the FDIC acts as receiver for insolvent national banks). ↑

- .12 U.S.C. § 1821(j) (2012). ↑

- .Hirsch Braver, Liquidation of Financial Institutions: A Treatise on the Law of Voluntary and Involuntary Liquidation of Banks, Trust Companies, and Building and Loan Associations § 1015, at 1182 (1936). ↑

- .Fed. Deposit Ins. Corp., Failed Bank List, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/individual /failed/banklist.html [https://perma.cc/AU5F-9LVM]. ↑

- .Cheryl D. Block, A Continuum Approach to Systemic Risk and Too-Big-to-Fail, 6 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. 289, 334–35 (2012). ↑

- .Dick, supra note 30, at 793–94. ↑

- .Onnig H. Dombalagian, Substance and Semblance in Investor Protection, 40 J. Corp. L. 599, 600 (2015). ↑

- .15 U.S.C. § 78ccc(e) (2012). ↑

- .See Jeanne L. Schroeder, Is Article 8 Finally Ready This Time? The Radical Reform of Secured Lending on Wall Street, 1994 Colum. Bus. L. Rev. 291, 463–64 (“SIPC buys [unsatisfied customer] claims . . . up to the statutory maximum amount . . . and is subrogated to the customers’ general credit claims against the debtor.”). ↑

- .15 U.S.C. §§ 78eee(a)(3)(A), 78eee(b)(1), 78ggg(b) (2012). The institution of a case under the SIPA brings any pending bankruptcy case to a halt. Irrespective of the automatic stay, the SIPC may file an application for a protective decree under SIPA. 11 U.S.C. § 742 (2012). ↑

- .15 U.S.C. § 78eee(b)(4) (2012). ↑

- .15 U.S.C. § 78fff-1(a) (2012); see also id. § 78fff-1(b)(2) (describing trustee’s conditional authority to guarantee all or part of the indebtedness of the debtor to a lender). ↑

- .Dombalagian, supra note 38, at 605. ↑

- .Stephen J. Lubben, Financial Institutions in Bankruptcy, 34 Seattle U. L. Rev. 1259, 1274 (2011). ↑

- .See generally, e.g., Cal. Ins. Code, §§ 1064.1–1064.13 (West 2012) (giving examples of insolvency under California state law). ↑

- .Iowa Code Ann. § 505.9 (West 2015). In New York, the regulator acting as receiver has a separate, dedicated staff, collectively known as the New York Liquidation Bureau. See also State ex rel. ISC Financial Corp. v. Kinder, 684 S.W.2d 910, 913 (Mo. Ct. App. W.D. 1985) (“The director of insurance is to be the receiver and he is to conduct the affairs of the receivership under the supervision of the court, in accordance with the statutory system.”). ↑

- .See Ala. Code § 27-34-50 (2007) (fraternal benefit societies); Del. Code Ann. tit. 18, § 5906 (West 2015) (domestic insurers); Haw. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 432:2-606 (LexisNexis 2014) (domestic societies); Iowa Code Ann. § 508.22 (West 2015) (life insurance companies); Nev. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 696B.220 (West 2015) (domestic insurers); N.Y. Ins. Law § 7405 (McKinney 2016) (domestic insurers); Utah Code Ann. § 31A-27a-401 (LexisNexis 2017) (domestic insurers); W. Va. Code Ann. § 33-10-6 (LexisNexis 2017) (domestic insurers). ↑

- .See, e.g., Ala. Code § 27-44-8 (2007) (capping liability at $100,000 in cash values per insured); Cal. Ins. Code § 1063.2 (West 2014) (describing the mechanics of compensating insured persons in case of an insurance company’s insolvency); Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 304.36-020 (LexisNexis 2011) (establishing funding for insured persons in cases of insurers’ insolvency); Mass. Gen. Laws Ann. ch. 175D, § 5 (West 2007) (same); 27 R.I. Gen. Laws Ann. § 27-34.3-8 (West 2017) (discussing the association’s ability to pay the impaired insurer’s contractual obligations); Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 26-42-106 (2018) (same); see also de la Fuente v. Fla. Ins. Guar. Ass’n, 202 So. 3d 396, 401 (Fla. 2016) (describing and applying Florida’s statutory fund for claims against insolvent insurance companies). In New York, there are three distinct, statutory security funds, known as the Property/Casualty Insurance Security Fund, the Public Motor Vehicle Security Fund and the Workers’ Compensation Security Fund. In addition, life insurance policy holders are protected by the Life Insurance Company Guaranty Corporation of New York, created under Article 77 of the State’s insurance law. See Ky. Ins. Guar. Ass’n v. Nat. Res. & Envtl. Prot. Cabinet, 885 S.W.2d 315, 316, 318 (Ky. Ct. App. 1994) (construing broadly Kentucky’s statutory fund for claims against insolvent insurance companies). ↑

- .Lubben, supra note 45, at 1268. ↑

- .Edward F. Greene & Joshua L. Boehm, The Limits of “Name-and-Shame” in International Financial Regulation, 97 Cornell L. Rev. 1083, 1106 (2012); see also Oscar Couwenberg & Stephen J. Lubben, Corporate Bankruptcy Tourists, 70 Bus. Law. 719, 722 (2015) (stating that “most large corporate groups have at least some international operations”). ↑

- .See Stavros Gadinis, From Independence to Politics in Financial Regulation, 101 Cal. L. Rev. 327, 371 (2013) (“Because insurance companies are state-regulated, the Act does not change states’ insolvency regimes but establishes a mechanism that allows the federal government to trigger the insolvency process at the state level.”); see also Matthew C. Turk, The Convergence of Insurance with Banking and Securities Industries, and the Limits of Regulatory Arbitrage in Finance, 2015 Colum. Bus. L. Rev. 967, 1007 (2015) (explaining how Dodd-Frank maintains a “decentralized state-led system”). ↑

- .See David Zaring, A Lack of Resolution, 60 Emory L.J. 97, 124 (2010) (detailing the complexity of commencing the resolution-powers process). ↑

- .12 U.S.C. § 5383(a)(1)(A) (2012). ↑

- .See id. § 5383(a)(1)(B). The statute provides:In the case of a broker or dealer, or in which the largest United States subsidiary (as measured by total assets as of the end of the previous calendar quarter) of a financial company is a broker or dealer, the Commission and the Board of Governors, at the request of the Secretary, or on their own initiative, shall consider whether to make the written recommendation . . . . ↑

- .Id. § 5383(a)(2)(A)–(C), (G). ↑

- .Id. § 5383(b). ↑

- .Id. § 5383(b)(1). ↑

- .Id. § 5383(c)(4). ↑

- .Id. § 5383(b)(2). ↑

- .Id. § 5383(b)(3). ↑

- .Id. §§ 5387, 5382(a)(1)(A)(i). ↑

- .See generally id. § 5390 (outlining the powers and duties of the FDIC once appointed as receiver). ↑

- .Companies that enter chapter 11 continue to be run by their existing management in almost all cases. The ongoing entity is known as the debtor in possession (DIP). DIP loans are typically asset-based, revolving working-capital facilities agreed to at the start of a chapter 11 case to provide both immediate cash as well as ongoing working capital during the process. ↑

- .Id. § 5390(n). ↑

- .Id. § 5390(n)(1). ↑

- .Id. § 5390(o). ↑

- .Id. § 5386. ↑

- .Id. § 5386(1). ↑

- .Id. § 5386(2)–(3). ↑

- .Id. § 5386(4). ↑

- .Id. § 5384(a). ↑

- .See generally Stephen J. Lubben, Resolution, Orderly and Otherwise: B of A in OLA, 81 U. Cin. L. Rev. 485 (2012) (examining the complexity of resolving Bank of America under OLA and accompanying issues). ↑

- .For a critical review of SPOE, see Stephen J. Lubben & Arthur Wilmarth, Jr., Too Big and Unable to Fail, 69 Fla. L. Rev. 1205 (2017). ↑

- .Kwon-Yong Jin, How to Eat an Elephant: Corporate Group Structure of Systemically Important Financial Institutions, Orderly Liquidation Authority, and Single Point of Entry Resolution, 124 Yale L.J. 1746, 1751–52 (2015). ↑

- .Jeffrey N. Gordon & Wolf-Georg Ringe, Bank Resolution in the European Banking Union: A Transatlantic Perspective on What It Would Take, 115 Colum. L. Rev. 1297, 1325 fig.3 (2015). ↑

- .Catherine Gallagher Fauver, The Long Journey to “Adequate”: Wells Fargo’s Resolution Plan, 36 Rev. Banking & Fin. L. 647, 658 (2017). ↑

- .Adrian H. Joline, Railway Reorganizations, 8 Am. Law. 507, 508 (1900) (referring to shareholders in railroad foreclosure cases). ↑

- .Edward J. Janger & John A.E. Pottow, Implementing Symmetric Treatment of Financial Contracts in Bankruptcy and Bank Resolution, 10 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. 155, 180 (2015); Jodie A. Kirshner, The Bankruptcy Safe Harbor in Light of Government Bailouts: Reifying the Significance of Bankruptcy as a Backstop to Financial Risk, 18 N.Y.U. J. Legis. & Pub. Pol’y 795, 831 (2015). ↑

- .Stephen J. Lubben, What’s Wrong with the Chapter 14 Proposal, Deal Book, N.Y. Times (Apr. 10, 2013), https://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/04/10/whats-wrong-with-the-chapter-14-proposal/?mcubz=3 [https://perma.cc/D97Z-U5SW]. ↑

- .Stephanie P. Massman, Developing a New Resolution Regime for Failed Systemically Important Financial Institutions: An Assessment of the Orderly Liquidation Authority, 89 Am. Bankr. L.J. 625, 637 (2015). One early version, which would have replaced Title II entirely, is reviewed in Bruce Grohsgal, Case in Brief Against “Chapter 14,” Am. Bankr. Inst. J., May 2014, at 44, 113. Instead of creating a new chapter 14 of the Code to deal with large financial institutions that seek bankruptcy protection, the Financial Institution Bankruptcy Act of 2014, passed by the House but never acted upon by the Senate, sought to create a new Subchapter V of the Code to deal with such entities. Compare H.R. 5421, 113th Cong. (2014) (enacted) with Financial Institution Bankruptcy Act of 2014, H.R. REP. NO. 113-630, at 11 (2014). The pending CHOICE Act, discussed later in this Paper, would combine the latter approach with a full repeal of Title II of Dodd-Frank. Financial CHOICE Act of 2017, H.R. 10 § III (as passed by House, June 18, 2017), https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/10/text#tocHF34EA86F881447208D253C613F969973 [https://perma.cc/TRC2-32M9]. ↑

- .For more on the 363 sale process, evaluated from a comparative perspective, see Stephanie Ben-Ishai & Stephen J. Lubben, Involuntary Creditors and Corporate Bankruptcy, 45 U.B.C. L. Rev. 253, 256, 272 (2012). ↑

- .Id. at 272. ↑

- .Lubben & Wilmarth, supra note 74. ↑

- .John Crawford, “Single Point of Entry”: The Promise and Limits of the Latest Cure for Bailouts, 109 Nw. U. L. Rev. Online 103, 107 (2014); Nizan Geslevich Packin, Supersize Them? Large Banks, Taxpayers and the Subsidies that Lay Between, 35 Nw. J. Int’l L. & Bus. 229, 276 (2015). ↑

- .Press Release, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Fed. Reserve, Federal Reserve Board Approves Final Rule Strengthening Supervision and Regulation of Large U.S. Bank Holding Companies and Foreign Banking Organizations (Feb. 18, 2014), https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20140218a.htm [https://perma.cc/BZD5-CAWP]. ↑

- .See Lubben & Woo, supra note 30, at 326–27 (predicting international regulators’ responses to banking regulations in the United States and the United Kingdom). ↑

- .Karl S. Okamoto, After the Bailout: Regulating Systemic Moral Hazard, 57 UCLA L. Rev. 183, 195 (2009); Morgan Ricks, Regulating Money Creation After the Crisis, 1 Harv. Bus. L. Rev. 75, 97 (2011). ↑

- .Jeffrey N. Gordon & Christopher Muller, Confronting Financial Crisis: Dodd-Frank’s Dangers and the Case for a Systemic Emergency Insurance Fund, 28 Yale J. on Reg. 151, 158, 162 (2011). ↑

- .Kathryn Judge, The Importance of “Money,” 130 Harv. L. Rev. 1148, 1150 (2017) (reviewing Morgan Ricks, The Money Problem: Rethinking Financial Regulation (2016)). ↑

- .Westbrook, supra note 1, at 243. ↑

- .Begier v. IRS, 496 U.S. 53, 58 (1990). ↑

- .See Chrystin Ondersma, Shadow Banking and Financial Distress: The Treatment of “Money-Claims” in Bankruptcy, 2013 Colum. Bus. L. Rev. 79, 106 (“[Not] all creditors have always been treated equally without exception; secured creditors are protected up to the value of their collateral . . . .”). ↑

- .See Stephen J. Lubben, The Overstated Absolute Priority Rule, 21 Fordham J. Corp. & Fin. L. 581, 605 (2016) (“Operating companies pay creditors according to business needs, without regard for actual priority.”). ↑

- .See Maxx M. Johnson, The Not-So-Settled Absolute Priority Rule: The Continued Threat of Priority-Deviation Through Interim Distributions of Assets in Chapter 11 Bankruptcy, 13 Seton Hall Cir. Rev. 291, 294 (2017) (“Priority for creditors could mean the difference between getting paid in full and not getting paid at all.”). ↑

- .See Michelle M. Harner, The Search for an Unbiased Fiduciary in Corporate Reorganizations, 86 Notre Dame L. Rev. 469, 494 (2011) (“The creditor’s objective and pursuit of control . . . might conflict with the debtor’s restructuring plan or the efforts of other creditors or shareholders to influence the process.”). ↑

- .See Chrystin Ondersma, Employment Patterns in Relation to Bankruptcy, 83 Am. Bankr. L.J. 237, 247 (2009) (finding that companies lose around fifty percent of employees in the years near bankruptcy filing). ↑

- .Rue21, Inc., rue21 Completes Financial Restructuring Process, PR Newswire (Sept. 22, 2017), https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/rue21-completes-financial-restructuring-process-300524488.html [https://perma.cc/JQA3-5Q66]. ↑

- .First Amended Debtors’ Disclosure Statement for the Debtors’ First Amended Joint Plan of Reorganization Pursuant to chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code at 10, 25, In re rue21, Inc., 575 B.R. 90 (Bankr. W.D. Pa. 2017) (No. 17-22045). ↑

- .Id. at 12, 26. ↑

- .Id. at 16–17. ↑

- .On the general construction of corporate bankruptcy systems, see Oscar Couwenberg & Stephen J. Lubben, Essential Corporate Bankruptcy Law, 16 Eur. Bus. Org. L. Rev. 39, 42–44 (2015). ↑

- .Richard M. Hynes & Steven D. Walt, Why Banks Are Not Allowed in Bankruptcy, 67 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 985, 989 (2010). ↑

- .See In re Bernard L. Madoff Inv. Sec. LLC, 654 F.3d 229, 240 (2d Cir. 2011) (noting that the “SIPC provides advances on customer property”). To be sure, if we view broker–dealers as holding assets in custody on behalf of their clients, they are somewhat different from the other financial institutions because it is not that clients receive preferential treatment vis-à-vis other creditors. Rather, it is that their assets never formed part of the bankrupt broker–dealer’s estate in the first instance. Of course, we also backstop that segregation from the estate with a special insurance fund, which then pushes broker–dealers a bit closer to the traditional financial institutions. Perhaps it is best to admit that they operate under a somewhat mixed model. ↑

- .Paul Lund, The Decline of Federal Common Law, 76 B.U. L. Rev. 895, 950–51 (1996). ↑

- .Stephen J. Lubben, Failure of the Clearinghouse: Dodd-Frank’s Fatal Flaw?, 10 Va. L. & Bus. Rev. 127, 152 (2015); Rizwaan J. Mokal, Liquidity, Systemic Risk, and the Bankruptcy Treatment of Financial Contracts, 10 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. 15, 43 n.21 (2015). ↑

- .Edward J. Janger, Response, Arbitraging Systemic Risk: System Definition, Risk Definition, Systemic Interaction, and the Problem of Asymmetric Treatment, 92 Texas L. Rev. See Also 217, 228–29 (2013). ↑

- .John J. Chung, From Feudal Land Contracts to Financial Derivatives: The Treatment of Status Through Specific Performance, 29 Rev. Banking & Fin. L. 107, 136, 138–39 (2009). For a general critique of the policymaking behind the safe harbors, see Stephen J. Lubben, Subsidizing Liquidity or Subsidizing Markets? Safe Harbors, Derivatives, and Finance, 91 Am. Bankr. L.J. 463, 472–77 (2017). ↑

- .Helen A. Garten, A Political Analysis of Bank Failure Resolution, 74 B.U. L. Rev. 429, 445 (1994). ↑

- .For key insights into the tensions that naturally exist between the bank and bankruptcy frameworks, see Sarah Pei Woo, Simultaneous Distress of Residential Developers and Their Secured Lenders: An Analysis of Bankruptcy & Bank Regulation, 15 Fordham J. Corp. & Fin. L. 617, 664–76 (2010). ↑

- .See Thomas W. Joo, Who Watches the Watchers? The Securities Investor Protection Act, Investor Confidence, and the Subsidization of Failure, 72 S. Cal. L. Rev. 1071, 1105 (1999) (“SIPA’s goals are very different. It is concerned primarily with the health of the securities industry. SIPA does not attempt to maximize the debtor’s estate . . . but only liquidation procedures.”). ↑

- .Staff of H. Comm. on Fin. Servs., 114th Cong., The Financial CHOICE Act: A Republican Proposal to Reform the Financial Regulatory System 26 (Comm. Print 2016), http://financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/financial_choice_act_comprehensiveoutline.pdf [https://perma.cc/3HU3-Y4F8]. ↑

- .Melissa B. Jacoby, Federalism Form and Function in the Detroit Bankruptcy, 33 Yale J. on Reg. 55, 69 (2016). ↑

- .See Anna Gelpern, Common Capital: A Thought Experiment in Cross-Border Resolution, 49 Tex. Int’l L.J. 355, 356 (2014) (“Like the public-policy functions, government commitments permeate the bank balance sheet. Central-bank liquidity support, deposit insurance, regulatory valuation of assets and liabilities, and resolution procedures all represent government commitments that shape the way in which a bank does business.”). ↑

- .See Donald F. Turner, The Scope of Antitrust and Other Economic Regulatory Policies, 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1207, 1233 (1969) (“In short, if banking is peculiar in that bank failures pose a particularly serious problem, it is also peculiar in that competition in lending performs a uniquely valuable function.”). ↑

- .Kristin N. Johnson, Things Fall Apart: Regulating the Credit Default Swap Commons, 82 U. Colo. L. Rev. 167, 185 (2011). ↑

- .See Adam J. Levitin, Safe Banking: Finance and Democracy, 83 U. Chi. L. Rev. 357, 361 (2016) (discussing ways in which banks’ lending practices aid in wealth creation). ↑

- .Money Stock & Debt Measures-H.6 Release, Fed. Res. Sys., https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h6/current/default.htm [https://perma.cc/FL8L-EBFM]. ↑

- .See Dan Awre & Kristin van Zwieten, The Shadow Payment System, 43 J. Corp. L. (forthcoming 2018) (manuscript at 31–32), http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2843772 [https://perma.cc/7LUQ-3XBA] (making this argument with regard to shadow payment systems). ↑

- .See Steven L. Schwarcz, Systemic Risk, 97 Geo. L.J. 193, 198 (2008) (explaining the wide-ranging economic consequences of failed financial institutions and the resultant need to account for systemic risk). ↑

- .See Saule T. Omarova, Bankers, Bureaucrats, and Guardians: Toward Tripartism in Financial Services Regulation, 37 J. Corp. L. 621, 627 (2012) (“Thus, financial crises directly implicate virtually every area of public concern, including housing, education, health care, labor markets, and environmental protection.”). ↑

- .See Melissa B. Jacoby, What Should Judges Do in Chapter 11?, 2015 U. Ill. L. Rev. 571, 580–81 (chronicling the widespread nature of “active case management” by judges in chapter 11 proceedings). ↑

- .Cf. Samuel L. Bufford, Coordination of Insolvency Cases for International Enterprise Groups: A Proposal, 86 Am. Bankr. L.J. 685, 692 (2012) (discussing the application of the pari passu principle to international insolvency cases); Christoph G. Paulus, The Interrelationship of Sovereign Debt and Distressed Banks: A European Perspective, 49 Tex. Int’l L.J. 201, 205 (2014) (highlighting the negative consequences of failing to follow the pari passu principle in international bankruptcy proceedings). ↑

- .Troy A. McKenzie, Judicial Independence, Autonomy, and the Bankruptcy Courts, 62 Stan. L. Rev. 747, 773–74 (2010). ↑

- .See Jonathan C. Lipson, Against Regulatory Displacement: An Institutional Analysis of Financial Crises, 17 U. Pa. J. Bus. L. 673, 710 (2015) (arguing that financial institution insolvencies are regulated to achieve the policy goals of legislative bodies and regulatory agencies). ↑

- .12 U.S.C. § 5382(a)(1)(A)(iv) (2012). ↑

- .E.g., id. §§ 5382(a)(1)(B), 5388, 5390(a)(9)(D). ↑

- .Financial CHOICE Act of 2017, H.R. 10, 115th Cong. Sec. 122, §§ 1181–1192 (2017) (as passed by the House June 8, 2017), https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/10/text/eh? [https://perma.cc/Y6EN-YU5H]. ↑

- .Id. § 1186. ↑

- .Id. § 1186(d). ↑

- .Id. § 1186(a)(1). ↑

- .Id. § 1185. ↑

- .Id. § 1186(a)(2). ↑

- .The regulators are given general standing to appear before the bankruptcy court. Id. § 1184. ↑

- .12 U.S.C. § 1841(b) (2012) (excluding any trust with terms of less than twenty-five years from the definition of “company,” resulting in such trusts not being subject to BHCA regulation). Presumably the bankruptcy court, particularly if asked by regulators, could order compliance with the BHCA when transferring estate assets to the trust. ↑

- .See generally Anat Admati & Martin Hellwig, The Bankers’ New Clothes: What’s Wrong with Banking and What To Do About It (2013) (arguing that despite superficial reforms in the wake of the recent recession, the banking industry still practices risky financial behaviors that reflect a fragile banking system). ↑

- .See Arthur E. Wilmarth, Jr., The Dodd-Frank Act: A Flawed and Inadequate Response to the Too-Big-to-Fail Problem, 89 Or. L. Rev. 951, 1023–24 (2011) (arguing that Dodd-Frank fails to eliminate the incentive for large banks to rely on federal bailout programs when considering risky activities). ↑

- .Henry T.C. Hu, Misunderstood Derivatives: The Causes of Informational Failure and the Promise of Regulatory Incrementalism, 102 Yale L.J. 1457, 1463 (1993); cf. Frank Pasquale, Law’s Acceleration of Finance: Redefining the Problem of High-Frequency Trading, 36 Cardozo L. Rev. 2085, 2114 (2015) (describing “the bleak realities at resource-starved agencies”). ↑

- .See Helen A. Garten, Regulatory Growing Pains: A Perspective on Bank Regulation in a Deregulatory Age, 57 Fordham L. Rev. 501, 536–37 (1989) (describing different capital-regulation approaches aimed at motivating banks to avoid risk-taking behavior). ↑

- .But see Jonathan R. Macey & Geoffrey P. Miller, Bank Failures, Risk Monitoring, and the Market for Bank Control, 88 Colum. L. Rev. 1153, 1157 (1988) (“Despite the surface plausibility of this theory, it is unlikely that a generalized bank panic like that which occurred during the Depression would occur today.”). ↑

- .See Edward J. Janger, Treatment of Financial Contracts in Bankruptcy and Bank Resolution, 10 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. 1, 4–5 (2015) (highlighting the disorderly outcome of non-FDIC-administered resolutions in comparison to the predictable and prompt process of bank insolvency proceedings). ↑

- .See Robert R. Bliss & George G. Kaufman, U.S. Corporate and Bank Insolvency Regimes: A Comparison and Evaluation, 2 Va. L. & Bus. Rev. 143, 176–77 (2007) (concluding that “[r]educing uncertainties surrounding the bank-insolvency-resolution process would further reduce the adverse externalities from bank insolvencies” and “may also reduce the incentives for banks to engage in excessive risk taking and moral hazard”). ↑

- .Kenneth J. Caputo, Customer Claims in SIPA Liquidations: Claims Filing and the Impact of Ordinary Bankruptcy Standards on Post-Bar Date Claim Amendments in SIPA Proceedings, 20 Am. Bankr. Inst. L. Rev. 235, 243 n.48 (2012). ↑

- .Cf. Andrea M. Corcoran, Markets’ Self-Assessment and Improvement of Default Strategies After the Collapse of Barings, 2 Stan. J.L. Bus. & Fin. 265, 291 (1996) (asserting that flexibility in financial emergencies should not be compromised). ↑

- .Irit Mevorach, Beyond the Search for Certainty: Addressing the Cross-Border Resolution Gap, 10 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. 183, 213 (2015). ↑

- .Stephen J. Lubben, A New Understanding of the Bankruptcy Clause, 64 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 319, 409 (2013). ↑

- .See John Crawford, Lesson Unlearned?: Regulatory Reform and Financial Stability in the Trump Administration, 117 Colum. L. Rev. Online 127, 140 (2017) (“The CHOICE Act would repeal Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act and replace it with a new subchapter of the Bankruptcy Code, chapter 11, subchapter V.”). ↑

- .See Anna Gelpern, Financial Crisis Containment, 41 Conn. L. Rev. 1051, 1102–06 (2009) (reviewing the policies, procedures, and decisions evaluated in bankruptcy considerations). ↑

- .Hirsch Braver, Liquidation of Financial Institutions: A Treatise on the Law of Voluntary and Involuntary Liquidation of Banks, Trust Companies, and Building and Loan Associations § 501 (1936). ↑

- .See Hester Pierce, Eliminating Dodd-Frank’s Overrated Escape Hatch, RealClear Markets (May 25, 2017), https://www.realclearmarkets.com/articles/2017/05/25/eliminatingdodd-franksoverratedescapehatch102707.html [https://perma.cc/BN5V-W4AG] (calling bankruptcy “a predictable, time-tested, transparent mechanism”); see also Chadwick Welch, Dodd-Frank’s Title II Authority: A Disorderly Liquidation of Experience, Logic, and Due Process, 21 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 989, 992 (2013) (arguing that bank insolvency procedures “muddl[e] what should be a framework of transparent rules”). ↑

- .See Arthur E. Wilmarth, Jr., The Financial Industry’s Plan for Resolving Failed Megabanks Will Ensure Future Bailouts for Wall Street, 50 Ga. L. Rev. 43, 57–58, 58 n.57 (2015) (discussing the benefits of a Wall Street proposal to private actors). ↑

- .See Stephen J. Lubben, No Big Deal: The GM and Chrysler Cases in Context, 83 Am. Bankr. L.J. 531, 531, 536 (2009) (discussing governmental involvement in the Chrysler and General Motors chapter 11 bankruptcies). ↑

- .See Recent Case, State Nat’l Bank of Big Spring v. Lew, 795 F.3d 48 (D.C. Cir. 2015), 129 Harv. L. Rev. 835, 839 (2016) (describing future OLA litigation concerns). ↑