A Cautionary Tale Out of West Virginia: A Call for Robust Federal Financial Assurance Requirements for Hardrock Mining

Introduction

Extracting minerals from the earth is necessarily disruptive to the environment. Modern mining has tried to limit this disruption by using more efficient extraction methods and—as is the focus of this Note—by remediating and reclaiming mine areas once extraction is no longer commercially viable. Reclamation and remediation necessarily present a challenge because these activities take money—and lots of it. If a mine has been struggling to remain commercially viable for some time, operators are not likely to have a lot of cash on hand. Moreover, incentives to comply with local regulators and to maintain good relationships with local citizens are not effective when a firm is ready to skip town. For many years, these incentive mismatches led to a spate of abandoned mines across the country.

In 1977, Congress enacted legislation that addressed this concern for surface (strip) coal mining, mandating that applicants for these permits provide financial assurance that they would be able to successfully remediate the site upon closure.[1] Federal regulations also mandate that applicants for underground coal mines provide financial assurance sufficient to remediate the surface portion of their operations.[2]

Although the federal government has statutory authority under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) to mandate financial assurance that meets closure requirements for hardrock mines, as of yet it has chosen to defer to the states on this matter, excepting mines on federal land.[3] During the Obama Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA or the Agency) proposed a rule requiring hardrock miners to demonstrate financial ability to fund site remediation.[4] However, one year later the EPA issued a determination that further investigation in light of the comments received revealed that federal regulation was not necessary.[5] In 2020, the D.C. Circuit upheld that decision as being neither an arbitrary nor a capricious exercise of the Agency’s discretion.[6] The EPA’s determination by no way closes the door on a rule proposal in the future. As a law firm blog summarized the issue: “[T]he ultimate outcome . . . lies in the hands of the next administration.”[7]

And, indeed, there are some signs that the federal government may be reexamining the issue, as environmentalists and the mining industry are in rare alignment on the need to extract hardrock minerals to support the “Energy Transition.”[8] Both President Trump and President Biden promulgated executive orders supporting the domestic supply chain of critical minerals.[9]

In February 2022, President Biden reaffirmed his commitment “to build a clean energy supply chain stamped ‘Made in America’ . . . using products, parts, and materials, as well as minerals, right here that are in the United States of America.”[10] In this same address, President Biden announced federal investment in various lithium projects but warned that “[w]e have to ensure that these [mined] resources actually benefit folks in the communities where they live . . . so we can avoid the historical injustices that too many mining operations left behind in American towns.”[11]

Yet, even as President Biden seeks to signal his support for the Energy Transition and thereby appease those that longed for the Green New Deal, he must also make sure not to alienate those same voters when the realities of mining become manifest.[12] As such, the Administration promulgated the “Biden-Harris Administration Fundamental Principles for Domestic Mining Reform.”[13] This short document lays out a plan for “expanding domestic production in a timely manner” while abiding by “strong environmental, sustainability, safety, Tribal consultation and community engagement standards.”[14] It is unclear the extent to which the vision extends beyond federal land; the preamble emphasizes the need to update outdated laws for mining on federal land, but the rest of the document does not otherwise limit any of its proposals. Instead, the document only mentions the need for a “[f]ully [f]unded [h]ardrock [m]ine [r]eclamation [p]rogram.[15] Concurrently, the Department of the Interior announced a “new interagency working group on reforming hardrock mining laws.”[16]

The dangers of ineffective regulation are evinced by the scores of abandoned mines—deserted without proper remediation—crisscrossing the landscape of the United States. However, the threat does not remain in the past; as we sit poised at the precipice of a potential surge in domestic hardrock mining, Appalachian state governments are struggling to cover the costs of mine remediation that bankrupt mines are unable to shoulder.

This Note uses recent West Virginia litigation as a cautionary tale of state capture to argue that robust financial assurance requirements for mine closures must be regulated on the federal level. It does so in three parts. Part I provides a brief theoretical and factual background about negative-value property, and mine remediation in particular. Part II examines CERCLA, the statutory basis for the EPA’s authority to regulate hardrock mine closures. Finally, Part III provides a deep dive into West Virginia’s current mine-remediation crisis, using ERP Environmental Fund Inc.’s (ERP) bankruptcy to examine how state regulators were unable to sufficiently regulate the industry.

I. Remediation: Theory and Practice

A. Explanation of Terminology

At the outset, it is important to clarify the distinctions this Note will and will not be making between types of mining. For the most part, this Note elides the differences between different types of mines. A strip mine extracting coal in Kentucky is going to pose different environmental risks than a copper pit mine in Montana; moreover, their remediation processes will be different. Because this is not a technical paper, it suffices to note that both types of mines will have remediation costs. In other words, although remediation is a site-specific process, the central issue of how to ensure payment for remediation costs upon mine closure is common to all sites.

However, this Note does draw distinctions between coal and hardrock mines because they are covered under different legal regimes. The EPA defines hardrock mining as the “extraction and beneficiation of rock and other materials from the earth that contain a target metallic or non-fuel non-metallic mineral.”[17]

B. Theoretical and Factual Background

Mine remediation is an expensive process. Although responsible operators try to remediate the mine environment as they work—a process called concurrent reclamation—some remediation will necessarily take place at the time of closure. As any home cook knows, there is always a mess to clean up even if you try to clean as you go. However, to torture the metaphor further, home cooks are naturally incentivized to clean up in a way that mine operators are not: home cooks clean to protect the value of their home. Mine operators looking to close up shop do not want to spend millions of dollars on property that they are hoping to leave. Professor Bruce Huber uses the example of used-up mines to demonstrate how challenging it is to regulate good stewardship of “negative-value property.”[18] Huber writes that environmentally minded folks have looked to property rights as a solution to the well-known tragedy of the commons.[19] Vesting someone with an asset normally incentivizes the new owner to improve or at least maintain its value. This normal assumption does not hold for the extractive industry; the value of the land on which a mine sits is derived from the amount of desired minerals it contains, and to a mine owner, ownership of the land is incidental to ownership of the minerals to be taken from that land. Moreover, the remediation of that land after it has been disturbed is often extremely expensive, and there are likely to be few purchasers for even the best-remediated mine land.

As Professor Huber writes, the mine owner’s “incentives point to land depletion, not land protection.”[20] In short, absent regulation, a mine operator has no real incentive to remediate the land and is likely to simply abandon it. Even with regulation, operators may be able to “display boundless creativity” to “escape [cleanup] obligations altogether via a kind of functional abandonment.”[21] When that abandonment is successful, Professor Huber dubs the liability that is then imposed on the state as “temporal spillover, an externality foisted across time rather than space.”[22]

Indeed, the costs of rehabilitating mine land can stretch far into the future. For example, a defunct pit copper mine in Butte, Montana, filled with groundwater after operations ceased and the pumps were shut off.[23] Metal ore is often full of sulfides that can react with water to form sulfuric acid. The pit became the subject of news coverage when 342 migrating geese died after landing on the pond.[24] As a result, the EPA put in place a waterfowl mitigation plan consisting of “[g]unfire and electronic noisemakers” meant to “frighten birds away from the water and a house boat” meant to “‘haze’ any remaining birds.”[25] In addition to the costs associated with this annual waterfowl mitigation plan, the former mine operators settled to build a water treatment plant designed to purify and discharge enough of the water to ensure that the pit does not overflow.[26] Absent the design of a new remedial system, this plant will need to run in perpetuity.[27]

Who should pay for this kind of huge liability stretching forward forever? How can regulators incentivize internalization of these kinds of environmental liabilities in order to incentivize minimally intensive mining methodologies?

II. CERCLA Powers

A. Current Use of CERCLA in the Hardrock Context: Posterior Liability

Currently, there are no federal requirements to prospectively ensure environmentally responsible hardrock mine closure for facilities not located on federal land. Instead, federal action is limited to retrospective actions after problems have already arisen. These actions are promulgated under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, legislation intended “to promote the ‘timely cleanup of hazardous waste sites’ and to ensure that the costs of such cleanup efforts were borne by those responsible for the contamination.”[28] These retrospective actions can be accomplished either through an administrative order compelling responsible parties to clean up the site under CERCLA § 106 or through recovery from responsible parties of costs already incurred by the government to remediate the site under CERCLA § 107(a).[29] In addition to using cost-recovery suits, the government finances cleanup programs though CERCLA’s Hazardous Substance Superfund (the Superfund).[30]

The scale of such Superfund cleanup efforts can be staggering. In the above copper pit example, the EPA invoked CERCLA to impose liability on the former mine operators after the pit closed.[31] As of 2006, the EPA had completed or overseen remediation of seventy-four hardrock mining sites under CERCLA.[32] These sites had an average cleanup cost of around $22 million—almost $33 million in today’s dollars.[33] The same report stated that the average cleanup cost for “non-mega” hardrock mining sites (defined as sites costing less than $50 million to remediate) was “more than double the average cost of non-mega sites in other industries.”[34] During bankruptcy proceedings, one large company “estimated the total environmental claims filed against it to have been in excess of $5 billion.”[35] At one of their sites, the EPA and DOI had combined claims of over $2 billion.[36]

Although CERCLA does impose liability on a mine operator if it fails to remediate the land, it is hard to extract money from an entity to pay for a property that is no longer profitable. Moreover, the mine operator itself is often insolvent, and asserting a CERCLA claim in bankruptcy can be troublesome. As summarized in a 2005 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), the “EPA faces further challenges when companies file for bankruptcy, stemming from the differing goals of the bankruptcy code and federal environmental laws, the complexities of bankruptcy procedures and environmental cleanup programs, and EPA’s many information needs when dealing with bankruptcies.”[37]

State regulators have largely tried to control for this temptation by imposing financial assurance requirements on hardrock mine operators. These requirements vary in their severity from state to state. There is no federal oversight to ensure their sufficiency. Indeed, the GAO reported that in the fiscal years of 2008 through 2017, the federal government spent about $2.9 billion to “identify, clean up, and monitor hazards at abandoned hardrock mines,” but it had only recouped approximately $1 billion from responsible parties.[38]

B. Applying CERCLA Section 108(b) for a Federal Hardrock Financial Assurance Program

When it enacted CERCLA, Congress realized that certain kinds of facilities might need to provide proof of financial assurance sufficient to clean up their sites and mitigate the risk of hazardous discharges at the front end because the risk of unfunded cleanup was too high. Section 108(b) reflects these concerns:

Beginning not earlier than five years after December 11, 1980, the President shall promulgate requirements . . . that classes of facilities establish and maintain evidence of financial responsibility consistent with the degree and duration of risk associated with the production, transportation, treatment, storage, or disposal of hazardous substances. Not later than three years after December 11, 1980, the President shall identify those classes for which requirements will be first developed . . . .

The level of financial responsibility shall be . . . adjusted to protect against the level of risk which the President in his discretion believes is appropriate . . . .[39]

The December 11, 1983 deadline for class identification came and went. Decades passed. In 2005, the GAO urged the EPA to use its § 108(b) authority to require financial assurances for hardrock mining operators, citing a 1997 study showing that state requirements were insufficient.[40] Frustrated by the federal inaction, environmental groups sued the EPA three years later for its failure to identify classes of facilities deserving § 108(b) financial assurance requirements.[41] The California district court denied the EPA’s motion for summary judgment.[42] Soon after, the EPA issued a notice in the Federal Register identifying the hardrock mining industry as containing classes of facilities deserving of § 108(b) financial assurance regulation.[43]

Because § 108(b) “does not spell out a particular methodology by which the identification is to be made,” the EPA felt that the “repeated references to the concept of ‘risk’” within the section were fundamental.[44] The Agency then broke down risk into eight different factors meant to capture both the magnitude of an industry’s potential environmental liability and the probability of companies within the sector shirking their remediation obligations.[45] These considerations all weighed in favor of establishing classes of facilities within the hardrock mining industry as deserving of federal financial assurance requirements.

However, by 2014 the EPA had failed to promulgate any draft financial assurance rules, prompting another suit by environmental groups to compel the Agency to act, including—as the D.C. Circuit noted with perhaps a degree of amusement—some of the same petitioners that had sued years earlier in California.[46] The resolution of the suit set deadlines for the EPA to take action.[47]

In response, the EPA issued a draft rule days before a change in administration.[48] In its draft promulgation, the Agency wrote that it had considered and rejected a “more traditional financial responsibility . . . ‘closure plan’ alternative.”[49] This alternative would have required the EPA to promulgate “a set of technical engineering requirements” to identify “the engineering controls necessary to comp[l]ete a CERCLA-style clean up at a facility where the owner or operator had walked away and failed to complete reclamation and closure activities.”[50] These requirements and site-specific considerations would serve as the basis to determine the amount of financial assurance required.[51] This alternative approach would in effect provide a minimum standard for financial assurance accounting. As the Agency wrote, the approach would have “allow[ed] for more consistency among financial responsibility requirements nationally, as the CERCLA § 108(b) amount would in concept, fill in any gaps EPA identified under other programs.”[52]

Rejecting this alternative as presenting a “significant regulatory burden on the Agency,” potentially stepping on other federal and state programs with “expertise with mining regulation,” and being perhaps incompatible with the case-by-case retroactive nature of CERCLA, the Agency decided—instead of filling in the gaps with other programs—to impose an additional supplementary requirement on regulated industries to address the potential of CERCLA liability.[53] Unlike closure plans issued under permitting regimes, the proposed rule would not require extensive site-specific cost calculation. Instead, the amount of financial assurance required would be calculated based on a variety of prespecified variables (e.g., type of mining, number of shafts). The EPA acknowledged that this sort of broad-based cost calculation would presumably result in inaccurate calculations on a given site but allowed that across sites the averages would hold.[54]

Unsurprisingly, hardrock mining operators were unenthused by the proposition that they would potentially have to set aside additional financial assurance in addition to any assurances required at the state level. The proposed rule generated many comments and a variety of predictably colorful headlines from trade media.[55]

Ultimately, the EPA decided to withdraw the proposed rule, finding that federal and state programs and modern mining practices sufficiently reduced the risk that the CERCLA Superfund would have to finance remediation for currently operating hardrock mines.[56] In 2020, the D.C. Circuit upheld the EPA’s final rule as being neither arbitrary nor capricious.[57] In its decision, the court recognized that the statute provided wide latitude to the Executive Branch for determining the level of risk.[58]

Given the wide discretion afforded to the Executive by the statute as well as the background judicial deference given to agency decisions, the court’s upholding of the EPA’s decision not to regulate hardrock mines under § 108(b) makes sense. Indeed, there are many parts of the EPA’s initial rule proposal that do seem puzzling and unnecessarily onerous on mine operators. It does not make sense, as the EPA seemed to propose, to promulgate redundant financial assurance obligations on hardrock miners; miners should not have to obtain surety insurance or set aside collateral for both state and federal obligations looking to protect against the same risk of abandonment. However, the federal government is better positioned to regulate financial assurance than states are. The federal government should not duplicate state regulation, but instead preempt it by mandating a minimum degree of coverage across the industry.

This was the model that was attempted under the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act; however, states were able to satisfy this minimum degree too easily. Part III shows how state-run financial assurance programs can fail, as states are unable to spread risk and politicians seek to support local industry.

III. Current West Virginia Remediation Crisis

A. Statutory Framework: Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA)

Although early coal mining was done in deep underground shafts, surface mining became the dominant means of coal extraction in the twentieth century as technological improvements and workplace safety concerns made surface extraction more widely used.[59] The ugliness of resource extraction that had previously been hidden in mineshafts now stretched across mountaintops. Aside from the added visibility of surface mining, the additional surface area of rock exposed to air and water increased the occurrence of acid mine drainage, where uncovered sulfides oxidize to sulfuric acid.[60] Professor Huber quotes a “prescient economic analysis” from 1939 concluding that strip mining would eventually lower land value, consequentially lowering local revenue and hampering local institutions.[61] By the mid-nineteenth century, strip mining underwent national scrutiny as environmentalists found in Appalachia a cause celebrated for their nascent movement.[62] Concerned about the rise of strip mining and the potential for an environmental “race to the bottom” between states eager for coal mining revenue, Congress enacted the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act in 1977 (SMCRA).[63]

The SMCRA was intended to “strike a balance between the nation’s interests in protecting the environment from the adverse effects of surface coal mining and in assuring the coal supply essential to the nation’s energy requirements.”[64] Congress found that improvements both in surface mining technology and reclamation technology meant that “effective and reasonable regulation of surface coal mining operations by the States and by the Federal Government . . . is an appropriate and necessary means to minimize so far as practicable the adverse social, economic, and environmental effects of such mining operations.”[65] Two of the stated purposes of the Act were to “establish a nationwide program to protect society and the environment from the adverse effects of surface coal mining operations” and to “assure that surface mining operations are not conducted where reclamation as required by [the Act] is not feasible.”[66]

The Act also aimed to prohibit the kind of abandonment issues already seen by introducing an affirmative reclamation requirement backed up by some financial assurance on operating surface coal mines. Successful reclamation would restore mined land to “a condition capable of supporting the uses which it was capable of supporting prior to any mining.”[67] The SMCRA requires mine owners to submit a reclamation plan before starting extraction.[68] To protect against the threat of insolvency or abandonment, the SMCRA requires coal companies to post bonds “sufficient to assure the completion of the reclamation plan if the work had to be performed by the regulatory authority.”[69]

Congress indicated that it hoped for all coal-mining states to be the primary administrators of their own programs because local regulators would be best positioned to understand local geographies and threats. Because estimating the size of a given site’s reclamation cost ex ante is such a fact-intensive inquiry, it adds significant efficiency to the system if administrators are aware of baseline facts common to geographies in the area. As such, Congress cited the “diversity in terrain, climate, biologic, chemical, and other physical conditions,” as reason to place “the primary governmental responsibility for developing, authorizing, issuing, and enforcing regulations for surface mining and reclamation operations” on the states.[70]

However, under the Act the default administrator was the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSM) (housed under the Department of the Interior) until a state enacted its own federally approved program.[71] Once the OSM grants approval, however, the “the state administers the SMCRA independently and maintains ‘exclusive jurisdiction’ over the enforcement of the SMCRA minimum permitting standards.”[72] As of 2017, twenty-three of the twenty-five states with active coal mining had attained primary jurisdiction over the SMCRA regulatory scheme.[73]

This cooperative federalism structure is common to many environmental laws, but there is a surprising twist within the SMCRA. Many federal statutes require that states who obtain primary jurisdiction must enact regulations that are “at least as protective” as the federal minimums.[74] However, the SMCRA actually appears to allow for some broader latitude at the state level than it does at the federal. As stated above, the default federal model requires that a permittee provide financial assurance “sufficient to assure the completion of the reclamation plan.”[75] Although there have been criticisms that some of the ways that companies can demonstrate financial assurance do not adequately provide said assurance (most notably, self-bonding), at least in theory the federal model requires that permittees demonstrate that they are able to pay the full amount that each site will require to be remediated.

States can choose to relax that requirement. Under 30 C.F.R. § 800.11, the OSM may approve an alternative bonding system (ABS) but only if the ABS will achieve the dual aims of the bonding program: to ensure that the regulatory agency has “available sufficient money to complete the reclamation plan for any areas which may be in default at any time” and to “provide a substantial economic incentive for the permittee to comply with all reclamation provisions.”[76] In other words, an ABS can shift the requirement from a permittee needing to provide full assurance for the site in question to the state regulatory agency, so long as the state regulatory agency is able to remediate any sites that may be in default at any given time.

B. Bankruptcies Illustrate the Insufficiency of the State’s Financial Assurance Program

The current crisis in West Virginia provides a cautionary tale for the potential issues associated with allowing a state government to regulate one of its primary industries. The federal government approved West Virginia’s SMCRA program in 1981.[77] Although the basic model for reclamation bonds is to require a company to put aside or guarantee the full amount required for a given site’s reclamation, SMCRA allows states to use alternative bonding systems that include funds pooled across sites that may be drawn upon by contributors to the pool.

First, those applying for permits must post financial assurance for site-specific reclamation, which is capped at $5,000 per acre.[78] Notably, this cap has not been adjusted for inflation since it was set in 2001.[79] Moreover, the

cost of reclamation has just gotten more expensive over time; the Special Reclamation Fund Advisory Council found that reclamation costs for coal projects increased by 45% between 2013 and 2019, primarily due to higher water treatment costs.[80] Historical analysis indicates that these bonds have “historically covered 10% of actual reclamation cost.”[81]

Second, the state pays the shortfall out of the Special Reclamation Fund and Special Water Reclamation Trust Fund if the reclamation ends up costing more than the cap.[82] These funds are supported by a tax—currently 27.9 cents per ton of coal mined in state.[83] The combination of site-specific bonds and the Special Reclamation Fund is meant to be sufficient to “complete the reclamation plan[s] for any areas which may be in default at any time.”[84]

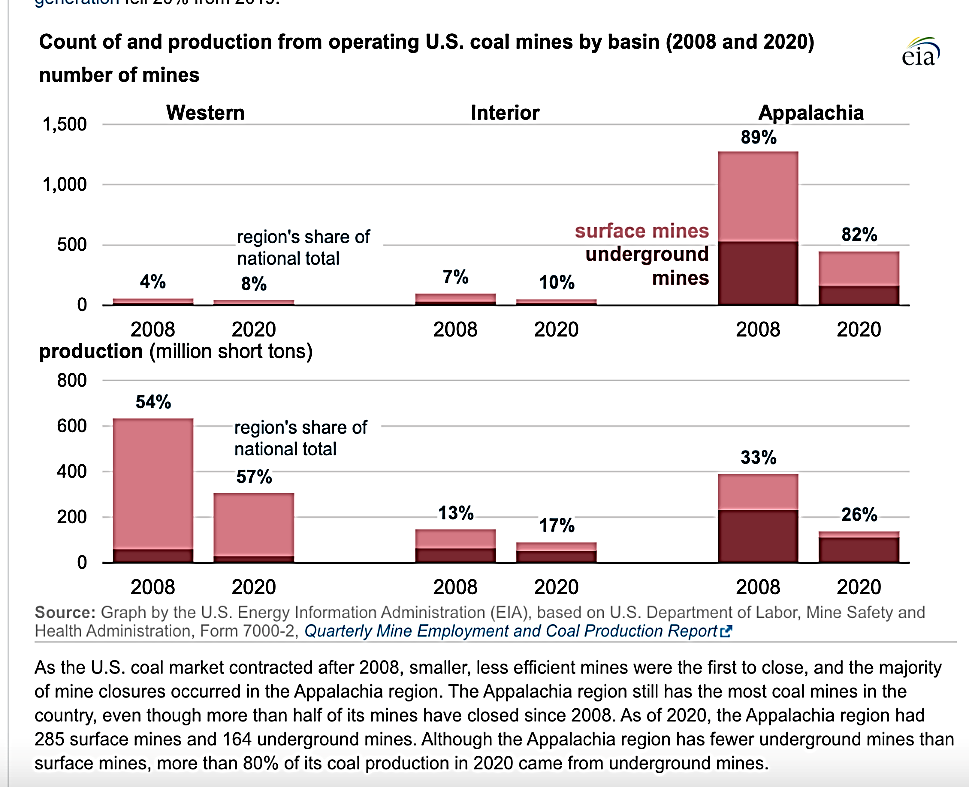

The recent decline of coal has shown how wrong that assessment is. The Special Reclamation Fund has been decimated on all sides in recent years; declining coal production in the state has led to both decreased money going into the Fund and an ever-increasing need for remediation as coal mines shutter operations.[85] As seen in Figure 1, more than half of Appalachia’s mines closed between 2008 and 2020 as coal production dwindled.

Figure 1[86]

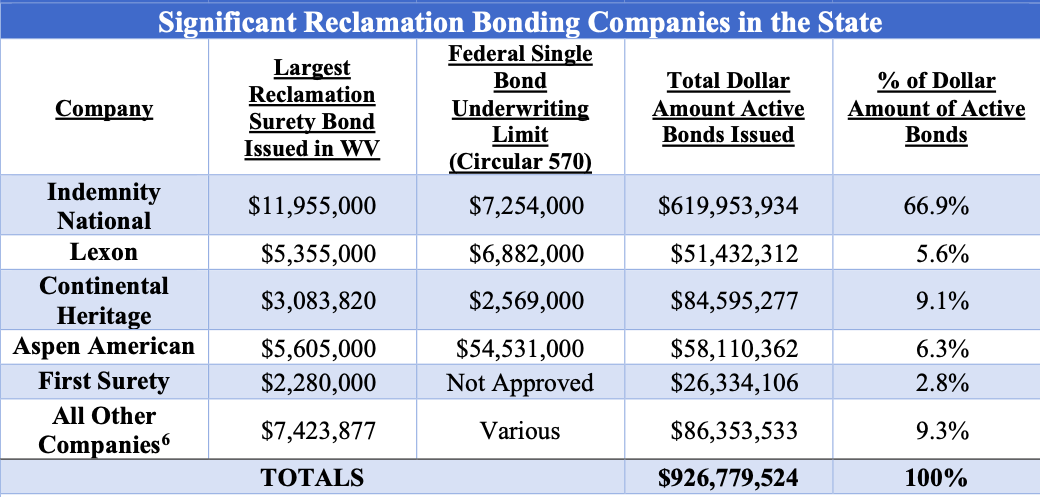

These twin pressures have led to a mine remediation crisis for the state. Too few funds are being spread too thin. A state audit report found that the balance at the time of the report ($190 million) covered “less than 40% of the projected 20-year liability” within the state.[87] This crisis has been exacerbated by another funding crisis; a 2021 report stated that 66.9% of active bonds are provided by a single surety company: Indemnity National.[88] Indeed, as Figure 2 demonstrates, more than 90% of the coal bonds in West Virginia are insured by just five insurers.

Figure 2[89]

This crisis came to a head in early 2020, when a company holding more than 100 mining permits fired all of its employees, stopped mining operations, and told the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (the WVDEP) that it did not have available funds to continue operation.[90] The company’s insolvency is worth a deeper investigation not only for the crisis that it provoked but also for its deeply dysfunctional history. In short, the circumstances of ERP Environmental Fund’s decline provide a concise window into some of the issues presented in allowing a state to police its own reclamation funds.

As is the case for all-too-many owners of mines at the end of their economic lives, ERP was not an experienced or particularly well-financed operation. The CEO was not an experienced coalminer; instead, he looked to operate the permits in a novel sort of way by combining the “reclamation and reforestation” of some permits with “[c]ontinued mining” at others.[91] This combination “bundles reforestation carbon credits with coal sales, effectively reducing carbon emissions” to meet the new emissions standards required by the permits.[92]

Initially, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection opposed the transfer of the permits to the relative newcomer with an ambitious scheme.[93] However, there were not many good alternatives. The 100 permits were only available because of Patriot Coal Corp.’s (Patriot) 2015 bankruptcy.[94] Moreover, they did not represent the best sites available due to Patriot’s bankruptcy; Patriot sold its valuable West Virginia assets to another firm, although this firm ultimately declared bankruptcy in 2019.[95] At the time of the transfer, the WVDEP estimated the costs of reclamation at $230 million.[96] Ultimately, the WVDEP dropped its opposition; it is hard to oppose a company that promised to remediate thousands of acres of liability-ridden land and increase employment in the area, as ERP did.[97]

When it acquired these unattractive properties, ERP met its financial assurance requirements largely through $115 million in surety bonds backed by insurance company Indemnity National.[98] The ambitious scheme struggled from the start, but the WVDEP was unable to do much to help right the capsizing ship. Instead, it just sent the company notice after notice of permit violation. Altogether, the WVDEP issued 160 notices of violations followed by 118 failure-to-abate cessation orders in an attempt to remedy the violations that were not addressed.[99] Then, when there were still remaining unabated violations, WVDEP issued “forty-one orders to show cause why the related permits should not be revoked.”[100]

In desperation, WVDEP allowed ERP to take $1 million from a collateralized remediation account that ERP had acquired as part of its purchase of the low-value mine sites in order to continue reclamation on its sites.[101] In exchange, ERP gave the WVDEP security interests in certain property and pledged to deposit all net proceeds from asset sales directly into the reclamation fund.[102] However, the WVDEP alleged that these assets were not only never sold but also further encumbered in order to secure debts to a law firm and as part of a forbearance agreement to settle litigation by environmental groups.[103]

When ERP laid off its employees in 2020,[104] WVDEP had limited options. ERP clearly did not have the cash to remediate the land covered by its more than a hundred permits. Indemnity insured $115 million of ERP’s bond obligations; WVDEP did not believe that Indemnity would be able to handle such a payout. The program was in crisis. More than 100 permits with millions in liability would be added to the list of the state’s liabilities, and the bond sureties did not look like they would be able to be collected.

WVDEP took to the courts in an effort to place ERP under receivership to allow the department to realize some portion of its debt from the company’s assets and to keep the permits from becoming the state’s responsibility. In its complaint, WVDEP alleged that ERP was frittering away its remaining valuable assets and sought to place the company under receivership to devote those resources to reclamation.[105] To support the claim that receivership was necessary, the Director of the Division of Mining and Reclamation and Deputy Secretary of the WVDEP, Harold Ward, voiced concern that any other alternative would have dire state-wide consequences. Ward stated that, in the case of continued default in the absence of an appointed receivership to satisfy ERP’s environmental obligations, the state would have to revoke all of ERP’s permits, transfer them to the state’s Reclamation Fund, and collect the $115 million pledged by the surety company.[106] On behalf of WVDEP, Ward expressed concern about the insurance company’s ability to actually pay up a $115 million lump sum.[107] Additionally, he stressed that transferring the 100 permits—and their estimated reclamation liability of $230 million in land remediation alone—would “overwhelm the [state-reclamation] fund both financially and administratively, with the result that the actual reclamation and remediation of the ERP mining sites could be delayed.”[108]

Ward’s strong words may have helped the court to grant the WVDEP’s request for receivership, but they also formed the basis for litigation against the department. In July 2020, environmental organizations brought suit against the WVDEP under the citizen-suit provision of the SMCRA alleging that the WVDEP had violated its nondiscretionary duty to report significant changes in the state’s SMCRA program to the OSM.[109] Section 732.17(b) of the Code of Federal Regulations requires administrators of federally approved state programs to “promptly notify the Director [of the OSM], in writing, of any significant events or proposed changes which affect the implementation, administration or enforcement of the approved State program.”[110] The Code then lists certain changes that state programs can make that would definitely require prompt federal notification, including “[s]ignificant changes in funding or budgeting relative to the approved program.”[111]

The environmental organizations’ complaint used Ward’s affidavit to show ERP’s ongoing permit violations,[112] WVDEP’s uncertainty about the $115 million in surety bonds,[113] and especially, Ward’s concern that transferring the permits to the state would “overwhelm the fund.”[114] The complaint alleges that WVDEP’s funds would be unable to adequately remediate the land even if the surety bonds were paid out in full because the fund’s $174 million would be almost fully wiped out by the $115 million remaining in land remediation, and the cost to address water issues would likely be more than $59 million.[115] Moreover, it alleges that the Special Receiver acknowledged that its $1 million budget was “insufficient” to address both earth remediation and water-discharge mitigation.[116] Lastly, the complaint also cites the bankruptcy or likely impending bankruptcy of three other major mining operators in the state.[117]

Indeed, WVDEP did try to walk back Ward’s strong claims in an attempt to cut off federal interference into its program. The environmental organizations alleged in their complaint that after they provided both WVDEP and the OSM notice of their intent to sue, WVDEP sent a letter to OSM denying “that any significant events had occurred.”[118] In denying WVDEP’s motion for summary judgment of the environmental organizations’ suit, the court cited a portion of WVDEP’s letter to the federal agency in which WVDEP again attempted to distance itself from its previous characterization of ERP’s insolvency by stating, “[s]ome allegations in the pleadings were to inform the Court of the possibility of a worst-case scenario such as the instantaneous melt down of ERP.”[119] The court noted in response that WVDEP’s statement was not clear, given that ERP was in material default under its permits and reclamation agreement, “does not have any employees or assets, and has ceased all operations.”[120] Additionally, in denying WVDEP’s motion to dismiss on Eleventh Amendment grounds, the court stressed that “whether a duty has been triggered is a factual question that is distinct from the issue of whether a duty is discretionary once it is triggered. . . . The use of the word ‘shall’ [in § 732.17(b)] indicates that it is a nondiscretionary duty.”[121] The court ultimately found that there was a plausible claim because the “alternative bonding system is an important source of funding for the state’s SMCRA program and may be significantly impacted when a major permit holder becomes insolvent.”[122]

This particular litigation ended with the environmental groups suing the OSM for failing to timely respond to the notice that they had provided to the federal agency about ERP’s insolvency threatening to “overwhelm” the West Virginian bond pool.[123] Ultimately, the OSM issued a formal declaration that West Virginia’s program required amendments to assure compliance.[124] First, the OSM required West Virginia to develop better tracking systems to keep permitting liability information up to date.[125] Second, the OSM requested that West Virginia provide it “with information necessary to demonstrate that its penal bond limits fulfill[ed] the requirements of 30 C.F.R. § 800.11(e).”[126] New legislation that became effective on June 6, 2022, addresses this first prong by “develop[ing] and maintain[ing] a database to track existing reclamation liabilities.”[127]

However, these fixes do not seem likely to remedy the situation that is acutely in crisis. Even after Ward worried in his affidavit that collecting on Indemnity’s pledged bonds would bankrupt the company and in turn render the Special Reclamation Funds insolvent, the WVDEP allowed Indemnity to underwrite an additional $170 million in mining reclamation bonds.[128] In humorously understated language, a recent report concluded: “[T]he Legislative Auditor questions the prudence of allowing surety companies to issue reclamation bonds without limitations on both the aggregate and single bond amounts.”[129] In less circumspect words, it was plainly illogical for the WVDEP to approve Indemnity’s additional underwriting when it was already concerned about the company’s ability to pay for the liabilities it had previously incurred. By placing ERP into receivership, the WVDEP was able to delay the inevitable insolvency of Indemnity, the state’s unofficial coal insurer,[130] and keep the party going for just a little longer. Clearly, however, it is aware that it is merely prolonging the inevitable check from coming due; how else to explain its approval of Indemnity’s underwriting of additional debt?

A 2021 legislative audit report publicized the dire state of West Virginia’s coal insurers, prompting the swift proposal and passage of a bill to create a new private mining mutual insurance company with a $50 million loan from the state’s general revenue fund.[131] This payment is, in theory, a noninterest loan which will be recouped in reclamation credits as projects are completed.[132] In practice, however, the dire state of the surety bond business does not provide much confidence that this money will be recouped. Rather, it seems like another attempt to prolong the inevitable.

Notably, a coal magnate signed the bill into legislation.[133] West Virginia Governor Jim Justice is presumably quite sympathetic to the dying industry; one newspaper article on the new legislation wryly observed that Forbes removed the governor from its list of billionaires in 2021 due to accumulation of corporate debt in connection to his own coal business.[134] Even more on the nose, a local activism group estimated that Governor Justice and his children owned nearly 34,000 acres requiring some degree of environmental cleanup.[135] Perhaps more objectively, in November 2021, a Kentucky state court found Governor Justice and his son personally liable for $2.9 million in environmental reclamation costs after failing to adhere to an earlier settlement order.[136]

The fact that the Governor happens to be a coal magnate troubled by environmental issues is just a fortuitous example of the dangers inherent in allowing for total state control of an issue that pits industry against environment. The capitol building in Charleston may be too far away from the coal mines to feel their environmental impact, but it certainly feels their financial impact. As illustrated in the ERP example, states do not have much leverage to deal with the liabilities associated with dying industries. WVDEP did not want to transfer the mining permits to ERP, but it had no other potential takers. When an industry is dying, any taker is better than none. Similarly, the West Virginia example shows how impossible it can be for a state to enforce its regulations when doing so would cripple a powerhouse industry. In other words, states are too tied to their mines to enforce closing liabilities when they are needed. As mines close, states are struggling too. On a federal level at least, there is a more diversified risk across the geographies and more diverse lobbying pressure. Moreover, a robust federal floor for financial assurance would reduce the risk of states racing to the bottom in order to attract investment in new hardrock mines.

Conclusion

West Virginia is a dramatic example of a phenomenon occurring all over Appalachia, as small mines shutter their operations and the state’s bonding regimes are put to the test. A 2018 GAO report found that operators forfeited over 450 financial assurances between July 2007 and June 2016 in thirteen of the twenty-five coal-country states, with the most forfeitures occurring in Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia.[137] The same report found that forfeiture bonds had only successfully completed reclamation in 52% of the cases nationally.[138]

At the very least, the panoply of coal bankruptcies over the past few years has shown that financial assurance bonding mechanisms are often inadequate to ensure proper mine reclamation. Although coal mining financial assurance programs operate under the shadow of national legislation, they are functionally run by the states. West Virginia illustrates that state governments have little ability (and possibly little incentive) to extract money out of a dying but still powerful industry. Conceivably, states are also ill-positioned to ensure the coal industry sets aside adequate money today to internalize future externalities, while also trying to maximize current employment and tax revenue.[139]

Looking at the fate of coal country’s reclamation funds in bust times should make us cautious about adequately funding reclamation for hardrock mines in this time of potential boom. More to the point, it should make us leery of the EPA’s conclusion that a final rule was not warranted partially because “site-specific assessments by on-the-ground [state] regulators” are “likely to better reflect actual response costs” than estimates by federal formulas.[140] It is true that state hardrock financial assurance methodologies instituted in the past few decades seem to be functioning well.[141] However, the final analysis must come in times of market decline, like in Appalachia today, when annual reclamation costs and liabilities dwarf profits. It is during those times of mass bankruptcy when state regulations, and regulators, will really be put to the test. To assure compliance with remediation commitments throughout a mine’s life, the EPA should establish a national framework that sets forth robust baseline standards.

In short, the federal government should exercise its CERCLA authority to institute a rigorous mandatory minimum of financial assurance coverage and ensure that state politicians do not succumb to the siren allure of prioritizing today’s campaign contributions and political power over tomorrow’s environmental security.

- . See generally Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, 30 U.S.C. §§ 1201–1328 (providing the requirements for reclamation plans in response to congressional findings that many surface coal mines were never remediated). ↑

- . 30 C.F.R. § 800.17 (2021). ↑

- . See Braden Murphy, Financial Assurance for Hardrock Mining: EPA and CERCLA, 94 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1855, 1856–57 (2019) (discussing how financial assurances for hardrock mining have been a matter of state regulation, even though CERCLA § 108(b) mandates federal promulgation of financial assurance requirements for especially high-risk “classes of facilities” (quoting 42 U.S.C. § 9608(b))). Note though, that the federal government has established reclamation requirements for hardrock mines on federal land. E.g., U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-19-436R, Hardrock Mining: BLM and Forest Service Hold Billions in Financial Assurances, but More Readily Available Information Could Assist with Monitoring 1–2 (2019). ↑

- . Financial Responsibility Requirements Under CERCLA § 108(b) for Classes of Facilities in the Hardrock Mining Industry, 82 Fed. Reg. 3388, 3388–89 (proposed Jan. 11, 2017) (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. pt. 320). ↑

- . Financial Responsibility Requirements Under CERCLA Section 108(b) for Classes of Facilities in the Hardrock Mining Industry, 83 Fed. Reg. 7556, 7556 (Feb. 21, 2018) (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. pt. 320). ↑

- . Idaho Conservation League v. Wheeler, 930 F.3d 494, 505 (D.C. Cir. 2019). ↑

- . Matthew Z. Leopold, Jennifer MikoLevine & Gregory R. Wall, EPA Declines to Impose CERCLA Financial Assurance Requirements on Three Industry Sectors, Nickel Rep. (Dec. 7, 2020), https://www.huntonnickelreportblog.com/2020/12/epa-declines-to-impose-cercla-financial-assurance-requirements-on-three-industry-sectors/#_ftnref7 [https://perma.cc/RP57-PN3U]. ↑

- . See Nikos Tsafos, Safeguarding Critical Minerals for the Energy Transition, Ctr. Strategic & Int’l Stud. (Jan. 13, 2022), https://www.csis.org/analysis/safeguarding-critical-minerals-energy-transition [https://perma.cc/KA7Z-SB5W] (“The transition from fossil fuels to low-carbon energy sources will depend on critical minerals.”). ↑

- . See Exec. Order No. 13953, 3 C.F.R. 451 (2021) (discussing minerals that “serve ‘an essential function in the manufacturing of a product, the absence of which would have significant consequences for our economy or our national security’”); see also Exec. Order No. 14017, 3 C.F.R. 521 (2022) (commanding the Secretary of Defense to identify risks in the supply chain for critical minerals and to describe and update work done pursuant to President Trump’s Executive Order No. 13953). ↑

- . Joe Biden, President of the United States of America, Remarks at a Virtual Event on Securing Critical Minerals for a Future Made in America (Feb. 22, 2022), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/02/22/remarks-by-president-biden-at-a-virtual-event-on-securing-critical-minerals-for-a-future-made-in-america/ [https://perma.cc/G333-BFVA]. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . See Ernest Scheyder & Steve Holland, Biden Voices Support for New U.S. Mines, If They Don’t Repeat Past Sins, Reuters (Feb. 22, 2022, 5:17 PM), https://money.usnews.com/investing/news/articles/2022-02-22/biden-set-to-tout-u-s-progress-on-critical-minerals-production [https://perma.cc/9G9K-CZH6] (describing President Biden’s address as an attempt “to boost U.S. output of lithium . . . and other strategic minerals while balancing opposition from environmental and indigenous groups”). ↑

- . Dep’t of Interior, Biden-Harris Administration Fundamental Principles for Domestic Mining Reform 1 (2022), https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/biden-harris-administration-fundamental-principles-for-domestic-mining-reform.pdf [https://perma.cc/7JBA-FL7A]. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. at 2. ↑

- . Press Release, Dep’t of Interior, Interior Department Launches Interagency Working Group on Mining Reform (Feb. 22, 2022), https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/interior-department-launches-interagency-working-group-mining-reform [https://perma.cc/UZ7H-U77R]. ↑

- . Financial Responsibility Requirements Under CERCLA § 108(b) for Classes of Facilities in the Hardrock Mining Industry, 82 Fed. Reg. 3388, 3390 (proposed Jan. 11, 2017) (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. pt. 320). ↑

- . Bruce R. Huber, Negative-Value Property, 98 Wash. U. L. Rev. 1461, 1471 (2021). ↑

- . Id. at 1462; see also id. at 1470 (“Although the assertion may seem counterintuitive, the key to land conservation is to bestow upon living persons property rights that extend perpetually into the future.” (quoting Robert C. Ellickson, Property in Land, 102 Yale L.J. 1315, 1369 (1993))). For an applied example of environmentalist-backed privatization of the commons, see generally Anna M. Birkenbach, Martin D. Smith & Stephanie Stefanski, Taking Stock of Catch Shares: Lessons from the Past and Directions for the Future, 13 Rev. Env’t Econ. & Pol’y 130 (2019). ↑

- . Huber, supra note 18, at 1471. ↑

- . Id. at 1465. ↑

- . Id. at 1466. ↑

- . Id. at 1475–76. ↑

- . Id. at 1475. ↑

- . Id. at 1475 n.61. Huber notes that these mitigation efforts failed in 2016, when at least 3,000 geese died from landing in the pond after a snowstorm disrupted their normal migration route. Id. A 2019 update listed the use of “drones, fireworks, lasers, and a sonic cannon” as new measures to prevent wildlife from landing in the toxic water. A Quick Look at Superfund in Butte, Montana, U.S. Env’t Prot. Agency, https://semspub.epa.gov/work/08/100006199.pdf [https://perma.cc/7VYN-JYJT]. ↑

- . Huber, supra note 18, at 1476; see also Nora Saks, Butte Reaches Superfund Milestone, Releasing Berkeley Pit Water into Silver Bow Creek, Mont. Pub. Radio (Oct. 1, 2019, 7:03 PM), https://www.mtpr.org/montana-news/2019-10-01/butte-reaches-superfund-milestone-releasing-berkeley-pit-water-into-silver-bow-creek [https://perma.cc/4CS5-A6SJ] (reporting on the treatment and release of water from Berkeley Pit). ↑

- . Huber, supra note 18, at 1476. ↑

- . Burlington N. & Santa Fe Ry. Co. v. United States, 556 U.S. 599, 602 (2009) (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting Consol. Edison Co. of N.Y. v. UGI Util., Inc., 423 F.3d 90, 94 (2d Cir. 2005)). ↑

- . Cooper Indus., Inc. v. Aviall Servs., Inc., 543 U.S. 157, 161 (2004). ↑

- . 42 U.S.C. § 9611(a). ↑

- . See A Quick Look at Superfund in Butte, Montana, supra note 25 (“Investigation and cleanup continues to be completed by the Atlantic Richfield Company and Montana Resources under EPA oversight.”). ↑

- . Jonathan L. Ramseur & Mark Reisch, Cong. Rsch. Serv., RL33426, Superfund: Overview and Selected Issues 17 (2006). ↑

- . Id. Consumer price index (CPI) conversion was calculated from January 2006 to September 2022 using the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ CPI Inflation Calculator. CPI Inflation Calculator, Bureau Lab. Stat., https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm [https://perma.cc/ZTE2-VCVE]. ↑

- . Ramseur & Reisch, supra note 32, at 17. ↑

- . Identification of Priority Classes of Facilities for Development of CERCLA Section 108(b) Financial Responsibility Requirements, 74 Fed. Reg. 37213, 37218 & n.49 (July 28, 2009) (discussing Asarco, LLC’s 2009 bankruptcy filing). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-05-658, Environmental Liabilities: EPA Should Do More to Ensure That Liable Parties Meet Their Cleanup Obligations 25 (2005) [hereinafter GAO-05-658]. ↑

- . U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-20-238, Abandoned Hardrock Mines: Information on Number of Mines, Expenditures, and Factors That Limit Efforts to Address Hazards 22 (2020). ↑

- . 42 U.S.C. § 9608(b)(1)–(2). The President delegated various presidential functions under CERCLA to the EPA. Exec. Order No. 12580, 3 C.F.R. 193 (1988). ↑

- . GAO-05-658, supra note 37, at 5 (“By its inaction on [§ 108(b)], EPA has continued to expose the [CERCLA] program, and ultimately the U.S. taxpayers, to potentially enormous cleanup costs at facilities that currently are not required to have financial assurances for cleanup costs, such as many gold, lead, and other hardrock mining sites . . . .”); id. at 36 n.68 (citing Off. Inspector Gen., EPA Can Do More to Minimize Hardrock Mining Liabilities, E1DMF6-08-0016-7100223 1, 11 (1997)). ↑

- . See Sierra Club v. Johnson, No. C-08-01409, 2009 WL 482248, at *1 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 25, 2009) (noting defendant EPA’s concession that “they have not carried out the actions required by Section 108(b),” including to “publish notice of the classes of facilities for which financial responsibility requirements would be required”). ↑

- . Id. at *6. ↑

- . Identification of Priority Classes of Facilities for Development of CERCLA Section 108(b) Financial Responsibility Requirements, 74 Fed. Reg. 37213, 37213 (July 28, 2009). ↑

- . Id. at 37214. ↑

- . See id. (listing factors, including the “extent of environmental contamination,” “projected clean-up expenditures,” and “corporate structure and bankruptcy potential”). ↑

- . In re Idaho Conservation League, 811 F.3d 502, 507 (D.C. Cir. 2016). ↑

- . See id. (“[T]he parties filed a joint motion for an order on consent establishing an agreed upon . . . timetable by which EPA would determine whether to engage in financial assurance rulemaking . . . .”). ↑

- . Financial Responsibility Requirements Under CERCLA § 108(b) for Classes of Facilities in the Hardrock Mining Industry, 82 Fed. Reg. 3388 (proposed on Jan. 11, 2017) (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. pt. 320). ↑

- . Id. at 3401. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . See id. (explaining that the proposed formula “aggregates . . . cost levels” across facilities but acknowledging inaccuracies in individual cost components). ↑

- . See, e.g., NMA Notes Growing Criticism of EPA’s Redundant Bonding Rules for Miners, Int’l Mining (Aug. 12, 2016), https://im-mining.com/2016/08/12/nma-notes-growing-criticism-of-epas-redundant-bonding-rules-for-miners/ [https://perma.cc/4UD4-ULNA] (“Now EPA is hearing criticism from every quarter. . . . All warn of a costly regulatory approach based on a superficial analysis that does not support the need for a redundant bonding requirement to ensure reclamation and other post-mining activities . . . .”); EPA Declines to Impose Unnecessary, Duplicative Financial Assurance Requirements on Mining Industry, Nat’l Mining Ass’n (Dec. 1, 2017), https://nma.org/2017/12/01/epa-declines-impose-unnecessary-duplicative-financial-assurance-requirements-mining-industry/ [https://perma.cc/Z3RA-LGVK] (“The National Mining Association (NMA) today welcomed the [EPA] decision that new, duplicative financial responsibility requirements for the hardrock mining industry are unnecessary.”). ↑

- . Financial Responsibility Requirements Under CERCLA Section 108(b) for Classes of Facilities in the Hardrock Mining Industry, 83 Fed. Reg. 7556, 7556 (Feb. 21, 2018) (to be codified at 40 C.F.R pt. 320). ↑

- . Idaho Conservation League v. Wheeler, 930 F.3d 494, 500 (D.C. Cir. 2019). ↑

- . Id. at 500, 504. ↑

- . See Robert F. Munn, The Development of Strip Mining in Southern Appalachia, 3 Appalachian J. 87, 90 (1975) (discussing the technology and equipment developments that made strip mining possible “in areas so rugged as to have been inaccessible a few years earlier”); Huber, supra note 18, at 1477 n.71 (“noting that surface mining accounted for 45% of U.S. coal production in 1970 and 59% by 1980” (citing Neal Shover, Donald A. Clelland & John Lynxwiler, Enforcement or Negotiation: Constructing a Regulatory Bureaucracy 17–18 (1986))). ↑

- . See Huber, supra note 18, at 1477. ↑

- . Id. at 1478. ↑

- . Munn, supra note 59, at 91 (“For the first time in decades, Appalachia was considered good copy by the media. . . . [S]urface mining provided an extremely attractive target, and the environmentalists made the most of it. By 1965 the surface mining industry was clearly on a collision course with public opinion.”). ↑

- . Ryan M. Yonk, Josh T. Smith & Arthur R. Wardle, Exploring the Policy Implications of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, Resources, Mar. 2019, at 2; see also 30 U.S.C. § 1201(g) (“[National] standards are essential in order to insure that competition in interstate commerce among sellers of coal produced in different States will not be used to undermine the ability of the several States to improve and maintain adequate standards on coal mining operations within their borders.”). ↑

- . Bragg v. W. Va. Coal Ass’n, 248 F.3d 275, 288 (4th Cir. 2001) (citing 30 U.S.C. § 1202(a), (d), (f)). ↑

- . 30 U.S.C. § 1201(e). ↑

- . Id. § 1202(a), (c). ↑

- . Id. § 1265(b)(2). ↑

- . Id. § 1258(a). ↑

- . Id. § 1259(a); 30 C.F.R. §§ 800.11, 800.14 (2021). ↑

- . 30 U.S.C. § 1201(f). ↑

- . Ohio Valley Env’t Coal. v. Caperton, 500 F. Supp. 3d 488, 492 (S.D. W. Va. 2020). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-18-305, Coal Mine Reclamation: Federal and State Agencies Face Challenges in Managing Billions in Financial Assurances 6 (2018) [hereinafter GAO-18-305] (“Of the 25 states and four Indian tribes that [OSM] identified as having active coal mining in 2017, 23 states had primacy, and [OSM] manages the coal program in 2 states and for the four Indian tribes.”). ↑

- . E.g., 15 U.S.C. § 2684(b)(1); 42 U.S.C. §§ 6945(d)(1)(C), 7543(b)(1). ↑

- . 30 U.S.C. § 1259(a); 30 C.F.R. §§ 800.11(e)(1), 800.14(b) (2021). ↑

- . 30 C.F.R. § 800.11(e) (2021). ↑

- . Id. § 948.10. ↑

- . Ohio Valley Env’t Coal. v. Caperton, 500 F. Supp. 3d 488, 493 (S.D. W. Va. 2020) (citing W. Va. Code § 22-3-11(a)). ↑

- . Joint Comm. on Gov’t & Fin. W. Va. Off. Leg. Auditor, WV Department of Environmental Protection Division of Mining & Reclamation – Special Reclamation Funds Report 13, 43 (2021) [hereinafter Special Reclamation Funds Report], https://www.wvlegislature.gov/legisdocs/reports/agency/PA/PA_2021_722.pdf [https://perma.cc/2VKW-Y24K]. ↑

- . Id. at 16. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id.; W. Va. Code § 22-3-11(g)(1)–(2) (2022). ↑

- . Special Reclamation Funds Report, supra note 79, at 14. For conciseness, I refer to funds derived from the tax simply as the Special Reclamation Fund, although a small portion of the fund is earmarked to address water contamination. See W. Va. Code § 22-3-11(m) (2022) (directing that revenue from the tax be deposited “to the credit of the Special Reclamation Fund and Special Reclamation Water Trust Fund”). ↑

- . Ohio Valley Env’t Coal. v. Caperton, 500 F. Supp. 3d 488, 493 (S.D. W. Va. 2020) (quoting 30 C.F.R. § 800.11(e)(1)). ↑

- . Special Reclamation Funds Report, supra note 79, at 14. ↑

- . The Number of Producing U.S. Coal Mines Fell in 2020, U.S. Energy Info. Admin. (July 30, 2021), https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=48936 [https://perma.cc/3YVM-AR7T]. ↑

- . Special Reclamation Funds Report, supra note 79, at 16. ↑

- . Id. at 19. ↑

- . Id. at 18. ↑

- . Erin Savage, “Environmentalist” Tom Clarke Abandons Mines in West Virginia, Appalachian Voices: Front Porch Blog (Apr. 3, 2020), https://appvoices.org/2020/04/03/tom-clarke-abandons-mines-in-west-virginia/ [https://perma.cc/8GXC-SCTC]; WVDEP Files Suit Against ERP Environmental Fund, W. Va. Dep’t Env’t Prot. (Mar. 27, 2020), https://dep.wv.gov/news/Pages/WVDEP-files-suit-against-ERP-Environmental-Fund.aspx [https://perma.cc/79AU-QUM3]. ↑

- . Patriot Coal Corp., Patriot Coal Enters into Agreement to Sell Certain Assets to Virginia Conservation Legacy Fund, PR Newswire (Aug. 17, 2015, 10:27 AM), https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/patriot-coal-enters-into-agreement-to-sell-certain-assets-to-virginia-conservation-legacy-fund-300129236.html [https://perma.cc/7JKG-TV9K]. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Affidavit of Harold D. Ward in Support of Plaintiff’s Motion for Temp. Restraining Ord. & Prelim. Injunc. & Temp. & Prelim. Appt. of a Special Receiver at 6, Ward v. ERP Env’t Fund, Inc., No. 20-C-282 (W. Va. Cir. Ct. Mar. 26, 2020) [hereinafter Ward Aff.], https://www.appvoices.org/resources/minereclamation/Ward_Affidavit_ERP_03262020.pdf [https://perma.cc/B6WH-F74N]. ↑

- . Id. at 4. ↑

- . Id. at 6; Special Reclamation Funds Report, supra note 79, at 15. ↑

- . Ward Aff., supra note 93, at 5; see also Patriot Coal Corp., supra note 91 (“VCLF/ERP is assuming liabilities in excess of $400 million in connection with Patriot’s workers’ compensation, state black lung and environmental obligations.”). ↑

- . Patriot Coal Corp., supra note 91. ↑

- . Ward Aff., supra note 93, at 11. Other funds for remediation came from a settlement agreement with the seller of the troubled assets. Id. at 6–7. ↑

- . Id. at 2. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. at 9. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. at 10. ↑

- . Zachary R. Mider, The Green Dreamer Who Became Big Coal’s Fall Guy, Bloomberg (Oct. 19, 2022, 5:00 AM), https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2022-west-virginia-coal-mining-tom-clarke/ [https://perma.cc/7375-T9A3]. ↑

- . Complaint at 2–3, Ward v. ERP Env’t Fund, Inc., No. 20-C-282 (W. Va. Cir. Ct. Mar. 26, 2020), https://appvoices.org/resources/minereclamation/WVDEP_ERP_complaint_03262020.pdf [https://perma.cc/J8BK-337Y]. ↑

- . Ward Aff., supra note 93, at 11. ↑

- . See id. (“DEP is concerned that forfeiting $115 million in surety bonds at more or less the same time could be problematic.”). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Ohio Valley Env’t Coal. v. Caperton, 500 F. Supp. 3d 488, 492–93 (S.D. W. Va. 2020); see also 30 U.S.C. § 1270(a)(1) (establishing the cause of action). ↑

- . 30 C.F.R. § 732.17(b) (2021). ↑

- . Id. § 732.17(b)(6); see also id. § 732.17(b)(7) (requiring notification for “[s]ignificant changes in the number or size of coal exploration or surface coal mining and reclamation operations in the State”). ↑

- . Complaint for Dec. & Injunc. Relief at 7, Ohio Valley Env’t Coal. v. Caperton, 500 F. Supp. 3d 488 (S.D. W. Va. 2020) (No. 3:20-cv-00470). ↑

- . Id. at 8. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. at 9. ↑

- . Id. at 9–10. ↑

- . Ohio Valley Env’t Coal. v. Caperton, 500 F. Supp. 3d 488, 497 (S.D. W. Va. 2020) (quoting the complaint). ↑

- . Id. at 498 (alteration in original) (citing the Ward Affidavit). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. at 502–03 (citing Sierra Club v. U.S. Army Corps of Eng’rs, 909 F.3d 635, 645 (4th Cir. 2018)). ↑

- . Id. at 497. ↑

- . Complaint at 1, 8, Ohio Valley Env’t Coal. v. Owens, No. 3:21-cv-00301, 2021 WL 2003868 (S.D. W. Va. filed May 17, 2021). ↑

- . Letter from Glenda H. Owens, Deputy Director, Off. of Surface Mining Reclamation & Enf’t, to Harold Ward, Secretary, West Virginia Dep’t of Env’t Prot. (Aug. 23, 2021), https://drive.google.com/file/d/1IRg6UyoQR0XnaZNuHPMa_QJFgYJ5cz5y/view [https://perma.cc/PXQ2-F46G]. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . W. VA. Code § 22-3-11 (2022). ↑

- . Special Reclamation Funds Report, supra note 79, at 21. ↑

- . Id. at 22. ↑

- . See Leslie Kaufman & Will Wade, The Tiny Insurance Company Standing Between Taxpayers and a Costly Coal Industry Bailout, Bloomberg (Nov. 8, 2022, 4:00 AM), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-11-08/the-tiny-insurance-company-standing-between-taxpayers-and-a-costly-coal-industry-bailout [https://perma.cc/R3M3-CT5M] (reporting that in West Virginia, Indemnity “holds 67% of the total, or $620 million” of the coal surety bonds “guaranteeing some of the cost of reclamation”). ↑

- . Mike Tony, Gov. Justice Signs Bill Establishing Mining Mutual Insurance Company with $50 Million in Taxpayer Money into Law, Charleston Gazette-Mail (Mar. 29, 2022), https://www.wvgazettemail.com/news/legislative_session/gov-justice-signs-bill-establishing-mining-mutual-insurance-company-with-50-million-in-taxpayer-money/article_c92b337e-ca7d-54c1-8486-4c4bdc0e1da1.html [https://perma.cc/LTU9-8RRW]. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Willie Dodson, Cleaning Up Mines Owned by Gov. Justice and His Family Would Create Hundreds of Jobs, Appalachian Voices: Front Porch Blog (Nov. 18, 2021), https://appvoices.org/2021/11/18/mine-reclamation-jim-justice-jobs/ [https://perma.cc/3VHL-8XAS]. ↑

- . Brandon Roberts, Judge Orders West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice to Pay $2.9M for Failure to Clean Up Eastern Kentucky Coal Mines, Spectrum News 1 (Nov. 11, 2021, 4:01 PM), https://spectrumnews1.com/ky/louisville/news/2021/11/11/judge-orders-wv-governor-to-pay–2-9-million-in-fines [https://perma.cc/M3E2-7AN5]. ↑

- . GAO-18-305, supra note 73, at 13 & n.24. ↑

- . Id. at 13. ↑

- . See Philip Peck & Knud Sinding, Financial Assurance and Mine Closure: Stakeholder Expectations and Effects on Operating Decisions, 34 Res. Pol’y 227, 232 (2009) (“Governments may be more interested in revenue than in total welfare. . . . It is conceivable that governments may be either indifferent about regulating externalities or enforcing regulations (or both) in order to prevent erosion of the tax base.”). ↑

- . Financial Responsibility Requirements Under CERCLA Section 108(b) for Classes of Facilities in the Hardrock Mining Industry, 83 Fed. Reg. 7556, 7568 (Feb. 21, 2018) (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. pt. 320). ↑

- . See id. (noting Nevada’s absence of taxpayer-funded remediation efforts since revisions to its remediation regulations in 1991). ↑