IP’s Pluralism Puzzle

Introduction

At the core of intellectual property (IP) law lies a fundamental question of political philosophy: Can any argument justify the state’s grant of private property rights in intangibles?[1] To this question, scholars have responded that IP rights can be justified by natural rights,[2] efficiency,[3] personality,[4] autonomy,[5] or good consequences, such as strengthening democracy.[6] Although offering different justifications, scholars in this canon share a “monist” theoretical approach, which attempts to justify IP rights by appealing to a single theory or value.

Monist arguments for IP are intuitive, but each faces serious objections. Economic rationales lack the empirical support necessary to show that welfare is higher with, rather than without, IP.[7] Lockean arguments struggle to explain how it is “natural” to own intangible public goods,[8] or why mixing one’s labor with the commons results in ownership of the resource rather than simply the alienation of one’s effort.[9] Democratic theories, like other consequence-sensitive arguments, share with economic theories a difficulty grappling with both the incentive-access trade-off and the paucity of empirical evidence showing how better consequences are achieved in a world with IP than in one without it.[10] And while personality and autonomy may plausibly provide a good argument for personal rights in relation to intangibles (for example, rights of attribution and integrity),[11] they provide scant reason why an author should enjoy property rights (such as the economic right of reproduction) after publication: Why does investing one’s personality in a work justify control of copying?[12] Given these objections, some conclude that there simply is no good argument for IP rights.[13] Others find the objections, while not necessarily conclusive, sufficient to instill a sense of existential worry in the heart of IP law.[14]

Not all IP lawyers, however, are monists. A central contention of this Essay is that there exists a growing—albeit somewhat vague and under-examined—feeling that IP rights are best justified on pluralist grounds. What we call “IP pluralism” is the view that a congeries of principles or values, rather than just one, can justify intellectual property.[15] Lying behind such pluralism is a frustration at the problems facing monist arguments but also a sense that IP in a liberal democracy should, in some respects, be pluralistic.

This Essay is the first to critically evaluate pluralist arguments for IP rights. In so doing, it identifies “IP’s pluralism puzzle”: Despite a reasonably common belief that a good pluralist argument for IP rights exists, no such argument can be found in literature. Indeed, this Essay identifies only four scholars who have explicitly attempted such an argument. This is itself surprising given how pluralism forms a central part of modern private law theory.[16] And, even more worrying, said pluralist arguments all face their own significant objections.

There is, therefore, a gap between the very commonly held beliefs of the IP community, and what beliefs can be reasonably and rationally defended. This gap is puzzling and calls out for some explanation. We offer three potential explanations for the puzzle’s persistence: apathy toward theoretical coherence, casual borrowing of pluralism from other areas of law, and conceptual ambiguity about “IP.”

The Essay unfolds in four parts. Part I distinguishes explanatory and interpretive pluralism from our main concern in this Essay: justificatory pluralism. Part II identifies the few existing pluralist arguments for IP provided by David Resnik, Michael Edward Kenneally, Robert Merges, and Justin Koo. Part III critically evaluates those arguments, highlighting the objections to them. Tellingly, these arguments share a general problem: Despite offering prima facie pluralist justifications, they frequently devolve back into monist arguments, with all the stock objections.[17] Finally, Part IV formally defines the puzzle and asks whether it can be solved or explained.

I. Justificatory Pluralism

This Part sets the scene for what is to follow by explaining the different types of theoretical inquiries and types of pluralism. Because our concern is with justification, subpart A distinguishes justificatory pluralism from explanatory and interpretive pluralism. Subpart B then introduces Professor Aditi Bagchi’s taxonomy of pluralist arguments in contract law, which we use in Part II to explain the existing pluralist arguments for IP.

A. Justification

Justification of law is separate and distinct from either explanation or interpretation of it. A justification provides normative reasons for having some form of law and is the domain of political and legal philosophy.[18] An explanation seeks to provide reasons for why we have a body of law as a positive and descriptive matter and is primarily the domain of legal history.[19] Both justification and explanation should be distinguished from interpretation, which provides arguments regarding the best interpretation of a doctrine or area of law, taking into account both historical social facts and practices, and the normative values that underlie them.[20]

To illustrate the differences between these distinct theoretical inquiries, consider the story of the early law and economics movement. In the 1970s, some in this community saw their work as primarily explaining how the common law incrementally developed over time to become an efficient body of rules.[21] However, when that positive explanatory claim was critiqued, leaders of the movement reconceived their project as primarily normative and justificatory. Rather than claim the common law was efficient, the movement shifted to claim that it ought to be efficient and reforms may be necessary.[22] That normative claim, however, was critiqued by Ronald Dworkin, who first argued that wealth is not a value.[23] Subsequently, Dworkin shifted the nature of the debate again, this time away from efficiency and towards the best interpretation of the law. Viewing the law in its “best light,” he contended, requires interpreting it as providing security for individual rights rather than the achievement of efficiency.[24]

We emphasize the separateness of these inquiries because our concern here is justificatory IP pluralism. The different strands of inquiry tend to become blurred in the IP pluralist literature. Because we are interested in evaluating only the justification for IP, we do not evaluate arguments that seek to explain why we have IP law as it exists or to provide the best interpretation of it. It is entirely plausible that different values have shaped IP’s direction or can be found within existing doctrine,[25] but that fact says nothing about whether we ought to have IP rights.

Lastly, we exclude from this analysis certain theoretical positions that incorporate plural values as part of an evaluative framework while not seeking to offer any justification for IP rights.[26] Our object of study is only those who seek to offer an explicit justification for IP rights.

B. Pluralism

In recent years, pluralism has become a central concern in private law theory. In reviewing the contract literature, Aditi Bagchi helpfully categorizes pluralist arguments into three camps: horizontal, vertical, and democratic.[27]

Both horizontal and vertical pluralist arguments are organized around structural principles. Horizontal pluralism “holds that distinct features of contract law . . . are animated by distinct principles and normative commitments.”[28] For example, “efficiency theories might explain and justify adjudicatory outcomes while autonomy theories explain and justify judicial reasoning.”[29] Contract law is, therefore, a patchwork of different doctrines, all justified by different but equally important normative commitments. Vertical pluralists, by contrast, “generally look to autonomy theories of contract to justify contract law at a high level but look to welfare analysis to justify specific doctrines.”[30] For example, contract law may be justified writ large by one value, but individual rules and principles, like promissory estoppel, may be justified by a separate value (e.g., efficiency).

Lastly, democratic pluralism is not organized around structural principles. Democratic pluralists instead seek to “legitimat[e] contract and contract law as social instruments and coercive state action.”[31] The question for such theorists is not necessarily how different values fit together within contract law, but instead how contract law fits into a modern democratic and pluralist state. Such theorists frequently make use of the idea of “overlapping consensus” popularized by John Rawls.[32] To Rawls, liberal democracies are surprisingly stable, despite the very significant differences between people: Although our citizens hold incompatible values, we do not see the same sort of tumultuous overthrowing of governments that many non-liberal democracies routinely do.[33] This surprising result occurs, according to Rawls, because enough citizens share a consensus regarding the basic features of our political state (e.g., that legislators make laws, the role of judicial review, etc.). While we arrive at this consensus through different means—a Christian fundamentalist may have different reasons for supporting this political entity than a progressive atheist, for example—we manage to reach some form of consensus anyway.

II. Pluralist Arguments for IP

In this Part, we use the framework from Part I to explain and categorize pluralist arguments for the existence of IP rights. Despite the seemingly common belief that there is a good pluralist justification for IP rights, the literature contains few explicit arguments for it. Indeed, we identify only four sources that come close to offering such an argument: one by David Resnik, a second by Michael Kenneally, a third by Robert Merges, and a fourth by Justin Koo. Subparts A, B, C, and D review each of these arguments, all of which tend to blend elements of horizontal, vertical, and democratic pluralism.

A. David Resnik

David Resnik seeks to provide a pluralist “account” of IP.[34] While at times that account has some interpretive qualities, it can also be understood as a justificatory pluralist argument. We are here only concerned with the justificatory claims. Using Bagchi’s terminology, we understand Resnik’s argument as primarily an example of horizontal pluralism, albeit with some elements of democratic pluralism.

Resnik’s horizontal pluralism acknowledges that no one single value can justify the vast array of IP rights. Rather, IP is a patchwork of different doctrines, all of which are justified by different, but equally important, values. On Resnik’s view, different arguments can justify distinctive aspects of contemporary IP and, therefore, the system as a whole. For example, he takes the view that there is generally a good utilitarian argument for many types of IP because “[m]any different studies document that IP promotes scientific discovery, technological innovation, and economic development.”[35] He acknowledges, however, that the utilitarian argument for moral rights—particularly the right of attribution—is speculative and, therefore, requires a non-utilitarian justification.[36] Similarly, Resnik also claims that while labor may provide a good reason for granting property rights in intangibles that require substantial efforts, rights in less time-consuming intangibles must be justified by an alternative argument.[37] Resnik’s approach reflects a horizontal, as opposed to vertical, structuring because he explicitly argues that different values may assume different levels of priority depending on context.[38]

Resnik offers two arguments for his horizontal pluralist account. First, because they all face objections, monistic approaches provide an “inadequate account of IP.”[39] As Resnik acknowledges, this is a “negative” reason for IP pluralism rather than a positive one. But he buttresses that argument with a second, more positive reason: IP is “highly diverse because there are many different ways of controlling and taking an interest in information.”[40] He cites interests in privacy, freedom, and authorship as interests other than economic ones that IP law might protect.

Lastly, Resnik offers a third argument for pluralism and, in so doing, introduces an element of democratic pluralism. Citing Rawls, Resnik contends that pluralism is attractive because “modern democratic societies are pluralistic,” and IP ought to reflect the diverse concerns of its citizens.[41] Pluralism enables IP law to respond to these varying interests by using a number of different values rather than a single one.

B. Michael Kenneally

Moving somewhere between horizontal and vertical pluralism, Kenneally claims small pockets of IP may be justified by natural rights claims, but vast swaths of contemporary IP law require a “social convention-type” (or “functionalist”) justification.[42] While the former focuses on the interests of IP owners, the latter “draw[s] attention to [and is supported by] interests that are shared widely throughout society.”[43] On his account, the core of IP is justified because it provides society with new inventions and works that would otherwise not exist.[44]

Beginning with natural rights, Kenneally argues that such claims “do support a few specific aspects of our intellectual property laws, but these are relatively few in number and modest in scope.”[45] Relying on a particular interpretation of Locke, Kenneally finds that individuals have interests in “obtaining material benefits through our labors” that ought to be protected against “wrongful interference.”[46] However, to make this idea defensible against the withering critiques of Robert Nozick and Jeremy Waldron regarding the “spooky metaphysics” associated with mixing labor,[47] he articulates this point very narrowly. In Kenneally’s interpretation, a laborer is merely entitled to a claim-right against wrongful interference with the laborer’s ability “to gain what is necessary or convenient for life.”[48] Applied to IP, the only wrongful interference Kenneally envisions is where the defendant uses the creation in such a way that would “lur[e] willing buyers away from the owner by charging a lower price.”[49] Ultimately, he continues, this may justify some aspects of trademarks, but Locke’s theory “does not offer a natural rights-type justification for . . . paradigmatic cases of copyright and patent infringement.”[50] Similarly, he also argues that autonomy interests justify only certain moral rights concerns.[51]

Because such arguments are quite restricted, “the core of patent and copyright law . . . are justified not by natural rights arguments . . . but by more functionalist lines of thought.”[52] Designers of an IP institution, on this view, should be “keenly aware” of overall welfare effects “but [should not be] utilitarians.”[53] Utilitarianism is unattractive for Kenneally because no one can agree about the nature of welfare or wellbeing (i.e., the utility produced by different types of copyrighted works), which creates unresolvable ranking problems.[54] Imagine, for example, two different worlds with two different types of national IP systems—systems A and B—that encourage the production of different types of creative works. System A produces more Hollywood movies and more Billboard 100 singles than independent works, while system B does the reverse. Kenneally argues that we cannot rank systems A and B in any meaningful way because different utilitarians disagree on (how to measure) the utility produced by Hollywood movies and independent works.[55]

The ranking problem leads Kenneally to articulate a rather modest idea about what would amount to a good functionalist justification for IP rights. This account’s central plank is a rejection of what he calls “comparative reasons”: reasons that are evaluated relative and superior to other reasons.[56] On some accounts, such as economic ones, we cannot justify adopting system A rather than system B unless we have a good reason to believe system A is better than system B. But Kenneally thinks that justifications need not depend on comparative reasons. For example, there are an infinite number of ways to cut a cake, and we might not know which cutting method is the best, but we also don’t need to: All we need is a reason “that support[s] [our] choice to cut the cake.”[57] In his words, “we should not presume that [an action supported by reasons] is something less than justified until we can show that it is more justified than alternatives.”[58]

Applying this mentality to IP, Kenneally argues that we don’t need to know what constitutes the best IP system to justify it as an institution. All we need are good reasons for having it. By setting aside questions about “whether it is as good as it could be,” we can instead ask a more basic question: Do copyright and patents “provid[e] the relevant incentives to produce the relevant sorts of intellectual goods [in a way that] furthers the interests of many”?[59] He gives the example of fair use and parody, where we might have normative reasons to favor the parodist over the copyright owner. Crucially, to determine whether parody is infringement, we do not need to calculate all the benefits and costs of allowing parody as fair use; instead, all we need to determine is whether there are good reasons to allow the parodist to make use of the original work and whether there are compelling reasons contrary to that rule. Decisions about allowing certain kinds of uses, like parodic uses, then, are not trapped by the ultimate value that justifies the basic institution.

With this conception of justification in place, Kenneally finally argues that “innovators, artists, and others who invest in creative endeavors would be reluctant to devote their resources to developing and commercializing inventions and expressive works in absence of special encouragement,” and therefore, copyright and patents are “largely justified by the widely shared interests of the members of a society in the availability of new inventions and creative works, not by the interests of inventors or artists themselves.”[60] With some qualifications, then, IP is justified by an incentive framework similar to, but not identical with, the general utilitarian framework.

C. Robert Merges

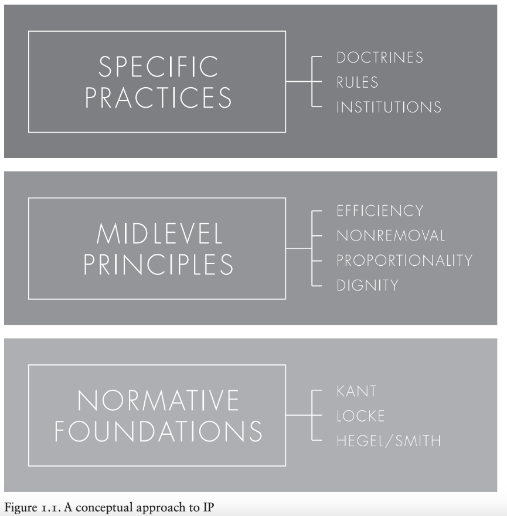

Unlike the prior two authors, Merges’s argument has clear features of “vertical structuralist pluralism.” Similar to the authors identified by Bagchi, Merges offers a hierarchical structure. In articulating a pluralist framework, he distinguishes between “normative foundations,” “midlevel principles,” and “specific practices” (see Figure).[61]

For Merges, normative foundations are the theoretical justifications of intellectual property law, such as those supplied by utilitarianism, deontology, or natural law.[62] Midlevel principles are concepts, like proportionality or efficiency, that are common across IP law and can be shared by those without identical normative commitments.[63] Finally, there are specific doctrines or practices in law that respond to practical problems.[64]

A conceptual approach to IP (Merges)

Merges is particularly interested in the distinction between the normative foundations based on autonomy, natural rights, and liberal distributive justice and the midlevel principle of efficiency. In an interesting parallel to vertical pluralists in contract law, utilitarianism and efficiency are pushed to the level of justifying certain practices and doctrines while non-utilitarian arguments provide the “high level” justification for the rights in the first place. This stands in contrast to Resnik’s horizontal pluralist approach, which justifies IP doctrines à la carte.

Merges’s account, however, also draws on democratic pluralism. Building on Rawls’s idea of overlapping consensus, Merges writes that the “great virtue of pluralism” is that it enables one to “engage in a meaningful way with those who are already convinced of the utilitarian account, those who hold firmly to deontological rights, and those who place their faith in other foundations altogether.”[65] Therefore, we all share some consensus that IP rights are broadly justified, although we do so for different foundational reasons. But the fact that we disagree on those foundational reasons does not prevent us from engaging with day-to-day IP law and policy.

D. Justin Koo

Like Merges, Justin Koo argues for a justification that blends elements of horizontal and democratic pluralism.[66] For Koo, the monist arguments all face significant objections.[67] Because of these objections, Koo asserts that “[c]opyright law has moved beyond the debate of whether a property right should be granted or not,” and accordingly, there is a need for a new kind of justification, one that “accounts for all of [copyright’s] nuances, diverse interests[,] . . . stakeholders[,] and competing considerations.”[68] In other words, Koo argues for a horizontal pluralism: Copyright can be justified by multiple values or interests because copyright responds to a variety of different concerns. As the nature of copyrighted works changes, copyright must respond by “be[ing] flexible and ready to adapt . . . to changes that reflect” current and future conditions.[69]

A “flexible” justification of copyright has two important effects, both of which suggest Koo’s pluralist justification is also democratic. First, to the extent that it responds to a broad array of interests, individuals will be more likely to perceive copyright law as legitimate than they would if copyright responded to a narrow array of interests.[70] Second, a pluralist and “flexible” justification is “important for developing copyright frameworks that are embracing hybridity.”[71] Pluralism is important here because it can provide justification for copyright systems that borrow from multiple jurisdictions.

III. Evaluation of Pluralist Arguments

This Part evaluates the pluralist justifications for IP offered by Resnik, Kenneally, Merges, and Koo. While these arguments have attractive features, each also faces important objections.

A. David Resnik

The objections to Resnik are fivefold.[72] First, Resnik arguably exaggerates how pluralist his account is. Recall that a central plank of his argument is that there is “good evidence” from “[m]any different studies” to support the utilitarian argument for IP rights.[73] This premise allows him to justify the core features of IP rights while using other values to justify some of the more marginal features of IP law (e.g., moral rights protections).

We are, however, less convinced of the existence of many different studies that provide a good utilitarian argument for IP rights. Rather, like Merges, we find the evidence “maddeningly inconclusive.”[74] While there certainly are arguments that support the case that IP rights promote creativity and innovation, the overall utilitarian calculation of all the costs and benefits that IP rights bring is far from clear. As a result, there is a long list of studies that bring the utilitarian argument into question.[75] Without strong evidentiary support, the utilitarian case for IP is not an obvious, or even likely, winner. Tellingly, if this central plank of Resnik’s argument fails, then there is very little left in the article that justifies the core and central feature of IP (i.e., ownership of intangibles).

Second, if Resnik is correct that there is a good utilitarian argument that justifies the core features of IP rights, that—somewhat paradoxically—actually undercuts the importance or need for a pluralist justification at all. At least from our perspective, if there is a good utilitarian argument that is theoretically and empirically grounded, then the debate is more or less over.[76]

Third, while we broadly agree with the claim that the monist accounts alone are inadequate, that premise does not logically entail the conclusion that a good pluralist account exists. Resnik seems to assume that this argument exists, and his job is to find it. But this assumption is defective because it concerns the truth of the very issue up for debate––namely, the justification of IP rights. Instead, we argue that if monism’s inadequacy is concerning, pluralism is a better option only if one can make a positive argument for it—one that is better than the accounts provided by monists.[77]

Fourth, while we agree with Resnik that IP is “highly diverse because there are many different ways of controlling and taking an interest in information,”[78] we disagree that this constitutes an argument for pluralism. Instead, we think this is better characterized as an argument against a broad definition of IP. In other words, if there is information in which we have privacy interests, we may protect those interests with laws relating to privacy (or something else), rather than property ownership. Pluralism is attractive here only if you think IP ought to account for interests like privacy. Many argue, we think rightly, it should not.[79]

Finally, Resnik’s argument from democratic pluralism does not supply sufficient normative justification of IP. Not all interests of citizens in a democracy are legitimate.[80] There is a long list of interests that democracies do not give protection in law, from hate speech to tax avoidance. If law should not reflect illegitimate concerns, neither should IP reflect all the “diverse concerns” identified by Resnik.[81] For example, simply preferring IP on the grounds it will make one rich does not seem to us like a legitimate interest, particularly if it makes many others substantially worse off. As the example shows, the whole point about pluralist societies is that people have different interests, and trade-offs need to be made: There will always be winners and losers. What is required is a normative argument (whether efficiency, natural rights, or other) that provides reasons to favor one set of interests over another. Simply pointing to the fact that pluralism is a reality fails to get us to the normative ought of justification.

B. Michael Kenneally

Many of the criticisms of Resnik apply to Kenneally. First, Kenneally’s argument faces similar evidentiary problems as other consequentialist accounts. If the “core” of IP is justified on the grounds that it produces incentives for creativity and innovation, then one might reasonably demand some good evidence that there are more creative works and inventions in a world with IP than in one without it. We have already explained how the evidence is decidedly mixed, if not dour, on that question. If that is true, then it is unclear why IP is justified even on Kenneally’s account. Secondly, and conversely, if there are good reasons to believe that there are more creative works and inventions in the world with IP, it is unclear why we should abandon monism in favor of pluralism.

Kenneally’s argument also suffers from a defect that others’ arguments do not: It uses a thin, and we think unjustified, approach to justification. Kenneally argues that a justified IP system need not be optimal or even demonstrably better than the alternatives. He rests this contention on an analogy to cutting cake, where there are equally plausible reasons for cutting the dessert in different ways.[82] However we cut the cake is likely justified—there is no winner-take-all reason to cut the cake in a particular way.[83] Deciding whether IP is justified, he claims, is like cutting a cake.

Justifying an IP system, however, is not like cutting a cake. Here Kenneally confuses justification among a set of justified options with justification of a set of justified options. Unlike the cake-cutting example, with IP we are trying to justify a set of justified options among which we can choose based on practical deliberation.[84] Among the set, it may not be possible to show which is the optimal system. But justifying a set of justified options requires showing that one or more options are better than the alternatives. To put things in Kenneally’s terms, IP is the cake. We are interested in determining whether there are any good reasons for baking the IP cake in the first place, not whether to slice it into moral rights or fair use.

A more plausible formulation of the argument is this: Once IP as an institution is justified, there are a range of justified options among which we can choose based on practical deliberation.[85] In Kenneally’s terms, once there are good reasons to bake the IP cake, we may be justified in deciding precisely what kind of IP cake we make and how we slice it up. But this does not seem to be true, even under Kenneally’s account, since there is little empirical evidence to justify the IP system on either a utilitarian or functionalist account.

C. Robert Merges

To begin, take Merges’s vertical structural pluralism, where arguments derived from Locke, Kant, and Rawls provide the “normative foundation” to the midlevel principles and doctrine.[86] Here is not the place to rehash all the objections to those arguments. Merges does an excellent job of producing the most plausible arguments for IP rights based on natural rights, autonomy, and distributive justice. Yet, the objections raised in the Introduction to those arguments remain: Lockean arguments rely on the rather strained claim that the ownership of intangible public goods is “natural”; autonomy provides a plausible argument for moral rights in said goods but very little reason why those goods need to be owned; and it is plausible that our world would contain a more just distribution of resources without IP rights rather than with them. Readers can simply decide whether they find the arguments, or objections to them, more persuasive.

Of course, if any of these arguments are good on their own, then Merges runs into one of the core problems facing Resnik and Kenneally: Why do we need pluralism? If the natural rights–labor argument, for example, is a good one, then the debate is, again, more or less over. That said, the importance of pluralism truly emerges only if we acknowledge that there is something objectionable about each of the quasi-Lockean, -Kantian, and -Rawlsian accounts. If so, then pluralism might actually do some important work. The question, in this case, is whether combining those arguments—particularly in the vertical way proposed by Merges—makes them stronger. Can they be more than the sum of their parts?

On its face, the answer would seem to be no. Combining two weak arguments does not add up to one strong argument absent some other argument. As an abstract example, consider that argument A faces objection X, and argument B faces objection Z. Adding argument A and B (i.e., A + B) does not negate the objections (i.e., X + Z), but simply replicates them in a new form. The addition of the arguments does not result in A + B – X – Z, but A + B + X + Z. Or, in less abstract terms, adding a Lockean argument facing significant objections to a rather limited-in-scope Kantian argument does not change the fact that the Lockean argument faces objections and the Kantian argument is limited in scope. Furthermore, this is also the case when seeking to combine two or more plausible arguments. Even if one takes the view that there is a plausible Lockean argument, a plausible utilitarian argument, and a plausible personality argument for IP rights, combining said arguments does not obviously result in a stronger argument; it merely results in another plausible one. A pluralist, then, must do more than simply combine weak normative arguments. He must produce some sort of argument as to why, when combined, the underlying arguments result in something more than the sum of their parts.

The idea of overlapping consensus does not do that job because when properly construed, the idea of overlapping consensus has very little to do with justification at all. In Political Liberalism, Rawls posed two questions: one about legitimacy (how is it legitimate to force some people to obey the law against their wishes?) and a second about stability (how is it that liberal democracies are relatively stable and not regularly overthrown in violent uprisings?). Rawls answered each question differently. Liberal democracies are legitimate—that is, justified—by a “political conception” of justice.[87] Put simply, it is legitimate to force some citizens to put up with law they do not agree with because, in some situations, it is just to do so. The idea of “overlapping consensus” plays no role in assessing whether states are justified in forcing citizens to obey its laws. It is, instead, about the stability question. That is, democracies are surprisingly stable because generally their citizens agree—all for their own individual reasons—to obey the law, even when doing so is not in their interest. Put differently, legitimacy addresses the theoretical question of justification while overlapping consensus addresses the practical question of stability.

In the context of IP, this means that it certainly would be nice to have an overlapping consensus, but its existence doesn’t justify the institution. If we all share an agreement that IP is justified—albeit for different reasons—then as a community we will find common ground, speak to one another with a sense of shared understanding, and quite probably be nicer to one another! While all of these outcomes are good, they still fall short of a justification. While this overlapping consensus would explain why IP laws exist and why they are not whimsically abolished by one government only to be reinstated by another, it would not tell us much about whether there are good normative justifications for IP which, in turn, would make it a legitimate institution.

D. Justin Koo

Koo’s arguments face significant objections—some of which also plague Resnik, Kenneally, and Merges. First, perhaps more than any other article, Koo’s does not even seek to offer a justification. In arguing that copyright has “moved beyond the debate of whether a property right should be granted or not,” Koo quite explicitly gives up attempting to offer any justification for property rights.[88] Instead, he moves toward some form of explanatory-interpretive “account” of existing copyright law.[89] Second, like Resnik, Koo offers a negative reason against monism but no positive convincing reason for pluralism. His negative argument that monist justifications all face significant problems does not constitute a positive argument that a pluralist justification is better. Third, Koo’s positive argument for pluralism gets things backward. Why start from the premise that IP, in its current form, is justified, and all that is left to do is find the right justification? The more interesting and important question is the prior one: Can IP be justified in the first place? Fourth, Koo’s arguments about legitimacy and hybrid legal systems, like Merges’s arguments on overlapping consensus, are not arguments about justification; they are about political stability. Therefore, they are not relevant to the question of whether IP is normatively justified.

One final point bears mentioning. Koo also argues that justification serves a limiting function. Since justification should, in principle, affect the application and development of the law, justification provides an important check against inappropriate doctrinal expansion.[90] Although we agree with this claim, we find it a curious one. Precisely because Koo’s objective is to justify current copyright law, it seems implausible that pluralism would constrain copyright law. To the contrary, if the goal is to provide a flexible and adaptable set of justifications for existing law, pluralism is likely to encourage, rather than constrain, the growth of law.

IV. Solving the Puzzle?

So far, we have made the following statements:

S1: There is a reasonably common belief among IP

scholars that a pluralist justification for IP rights exists.

S2: At present, the literature does not contain a good

pluralist justification for IP rights.

Those statements, on their own however, do not generate a puzzle. To generate a puzzle, or even a paradox, we need to add the following statement:

S3: Our beliefs about IP justifications are based on reason.

If these statements are all, on their face, true, then a puzzle emerges. If we cannot justify IP pluralism (S2) based on reason (S3), then why do many IP lawyers commonly believe one exists (S1)?

Subpart A addresses how to solve the puzzle. It finds each of the proposed solutions unsatisfying. Subpart B then tries to provide three competing explanations for why the puzzle remains despite our inability to solve it.

A. Possible Solutions to the Puzzle

Could the puzzle be solved? It could in three ways. First, one might disagree with S1. That is, perhaps we have exaggerated how commonly held a belief in IP pluralism is. Of course, it is difficult to support S1 with evidence or citations because much of our point is that such belief has not enjoyed sustained written consideration. Readers will need to make a judgment about whether they share our sense or not. But if S1 is wrong, then no puzzle exists: There is no particularly compelling justificatory pluralist argument, and generally that view is agreed with. Given our conversations with lawyers and academics, however, there are at least some who believe that S1 is correct.

A second way to solve the puzzle is to reject S2. If S2 is false, then once again, no puzzle exists: A general belief in pluralism (S1) is supported by good arguments (S2) that justify it based on reason (S3). Alternatively, even if existing written justifications face critical objections, one might argue (correctly) that such objections to existing arguments do not necessarily foreclose the existence of a different, more convincing pluralist justification. For example, S1 might reflect an intuition that a pluralist argument is out there, just waiting to be given written expression. While possible, the aim of this Essay is not to locate this theoretical unicorn. And, without it, we think that it is a mistake to guide institutional design choices with mere intuitions.

Lastly, but least plausibly, we could disagree with S3: that our beliefs are not the product of reason. And, to a certain extent, some have argued for this point.[91] We doubt, however, that many are willing to give up on reason just yet. And we count ourselves among them.

B. Possible Explanations for the Puzzle’s Persistence

Alternatively, if all statements are true, then the puzzle remains. In this subpart we present three explanations for the puzzle’s persistence: apathy, casual borrowing, and conceptual ambiguity.

By apathy, we mean that scholars may not care very much about whether IP is justified. Scholars may be understandably unmotivated for several reasons. Perhaps political philosophy and questions about the state’s actions are simply not things lawyers feel are within their domain. Rather than worrying about such philosophical questions, perhaps it is simply worth getting on with more concrete matters. IP is clearly a fixed feature of the legal landscape, and perhaps it is more practical, or simply more within the lawyer’s role, to worry about how existing IP rules could be best shaped to particular ends through doctrinal maneuvering. Finally, scholars may think that it simply does not matter what anchors IP because the decisions themselves are unlikely to be decided based on the doctrine’s underlying justification.

Besides apathy, scholars may also view pluralism as viable because they casually borrow pluralism from other areas where the approach is more defensible. Other areas of law are plausibly over-determined in the sense that many different justifications for them could persuasively be offered. From our perspective, for example, we think that there are many different justifications for tangible property rights, any of which on their own may be sufficient to justify some existence of property. For example, property rights might promote efficient use of resources or enable individuals to live meaningfully self-determined lives.[92] Similarly, some form of tort law may be plausibly justified on the grounds that it provides redress for wrongs, that it deters inefficient conduct, or both.[93] While we would not suggest these arguments are without objections, they are, in our minds, broadly supportive of the need for some form of property and tort law in a liberal democracy. Academic debate concerning such laws, therefore, tends to be more sympathetic to pluralist justifications, even if debate remains about how different values may conflict when embedded within legal doctrine. Looking at this debate, IP scholars may likewise think that the main question for IP is not justification, but simply pluralistic institutional design.

Finally, changes to IP doctrine and how it is discussed may make pluralism appear more attractive. Over the past fifty years, talk of IP has been invaded by ever-expanding concepts and rights from domains that do not match the criteria of patents and copyrights. The invasion has been both doctrinal and rhetorical. Doctrinally, for example, copyright has expanded in subject matter and scope.[94] And even core IP doctrines may be discussed or framed by reference to a multiplicity of values or concepts, like personhood, dignity, and autonomy. Rhetorically, trademarks, trade secrets, rights of publicity, and even rights of privacy have been discussed as “IP.”[95] All the while, the rhetoric of IP is supplemented by doctrinal expansions in areas like trademarks, which have ballooned in scope, encompassing broad, new rights that include merchandising, false endorsement, and dilution.[96] With such an expansive and inclusive view of IP, it is not hard to see why scholars would think pluralism could justify it.[97]

We find each of these explanations plausible but ultimately quite upsetting. Political apathy is not a good trait in any citizen, let alone lawyers. And even if IP is a fixed feature of our landscape, that does not mean thinking critically about the question is worthless or has no effect. As argued by Oren Bracha and Talha Syed in this volume, the decision to use an unrestrained market to channel the direction of creative and innovative activity results in the obvious “rights creep” that has characterized IP’s history.[98] As our normative values are “disembed[ded]” from the doctrine, said doctrine becomes increasingly incapable of any plausibly defensible social policy.[99] Such a process is, in our minds, even more likely when IP lawyers become apathetic about what values—if any—justify IP rights.

Casual adoption of pluralism is also worth worrying about. Unlike other areas of law, property in intangibles is not over-determined. Compared to property in tangibles or tort law, the arguments for intangible property rights are much more open for debate. If casual borrowing leads scholars to think that the main question of academic interest is merely institutional design, then the result is IP scholars misunderstanding what makes IP a unique and interesting area of law to think about—namely, the curious decision to grant private property rights in non-rivalrous resources. IP rights, unlike tangible property rights, is under-determined, not over-determined, and necessarily the type of debate around IP will be somewhat different to arguments in other areas of private law.

Finally, the expansion of IP may explain pluralism’s persistence, but we think it is a reason to resist rather than accept it. Defining IP means excluding certain content from its subject matter. Areas of law that do not meet the definition, such as privacy and rights of publicity, do not need any justification as IP. Broadening IP to areas other than copyright and patent manufactures a need to justify disparate regimes under one legal umbrella. Pluralism addresses this need, though it is a mistake to assume the need is genuine. One can see this misstep by starting with IP’s unexpanded justification and asking whether this justification warrants including other areas, such as privacy. The point can be made more broadly by asking a slightly different question: If IP includes a diverse and relatively unconnected set of legal rights, then what is IP? Expansion of IP to include too many concepts, in other words, renders it unintelligible: If IP is everything, then IP is nothing. If this is right, then our explanation for why pluralism persists only highlights why it should not.

Conclusion

Pluralist arguments for IP rights are intuitively attractive to many. By using a multiplicity of values to justify IP, rather than just one, such arguments might be useful to avoid the worst problems associated with each of the monist theories. Alas, for the most part, such pluralist arguments do not obviously escape the objections facing the monist arguments. Indeed, perhaps the biggest problem with the arguments of at least three IP pluralists—Resnik, Kenneally, and, to a more limited extent, Merges—is that, when stripped to their essentials, they are surprisingly monist. Both Resnik and Kenneally suggest the main argument for the core of IP is that it satisfies some form of consequentialist cost–benefit analysis—a claim we do not find convincing. Merges, somewhat similarly, marshals a pluralist justification primarily by binding together several monist arguments, each of which faces its own significant objections. The fourth pluralist, Justin Koo, appears to shy away from a normative justification almost entirely.

And yet, faith in some form of pluralist argument for IP persists. Why? This, in a nutshell, is IP’s pluralism puzzle. We tried, on the one hand, to solve this puzzle and, on the other, to explain it. One can solve the puzzle by rejecting our claims that IP pluralism is common, that no good written arguments for it exist, or that justifications for IP are based on reason. But since we find these rejections unconvincing, the best we can do is try to explain the persistency of the puzzle. Possible explanations can be found in an apathetic attitude to political philosophy, casual borrowing of ideas from other debates that are not similarly situated, and trading on an ambiguity about what is or is not “IP.” Such explanations are upsetting for a range of reasons: from their ability to contribute to “rights creep,” to their misunderstanding of what makes IP unique and intellectually interesting in the first place, and to the lack of faith in reasoned critical analysis.

- . IP law here refers to copyrights, patents, and design rights. Such rights share broadly similar conceptual and normative attributes, which can be discussed together. ↑

- . See generally Wendy J. Gordon, A Property Right in Self-Expression: Equality and Individualism in the Natural Law of Intellectual Property, 102 Yale L.J. 1533 (1993) (arguing that “a properly conceived natural-rights theory of intellectual property would provide significant protection for free speech interests.”). ↑

- . See generally William M. Landes & Richard A. Posner, The Economic Structure of Intellectual Property Law (2003) (explaining that intellectual property law is largely shaped by “efficiency considerations” and can be better understood through economic analysis). ↑

- . See generally Justin Hughes, The Philosophy of Intellectual Property, 77 Geo. L.J. 287 (1988) (presenting a “personality theory” of intellectual property as the “main alternative to a labor justification”); Neil Netanel, Copyright Alienability Restrictions and the Enhancement of Author Autonomy: A Normative Evaluation, 24 Rutgers L.J. 347 (1993) (presenting a theory of intellectual property that regards “literary and artistic works as inalienable extensions of the author’s personality.”); Neil Netanel, Alienability Restrictions and the Enhancement of Author Autonomy in United States and Continental Copyright Law, 12 Cardozo Arts & Ent. L.J. 1 (1994) (comparing the Continental European theory of personality in copyright law with the traditional American theory of property in copyright law); Justin Hughes, The Personality Interest of Artists and Inventors in Intellectual Property, 16 Cardozo Arts & Ent. L.J. 81 (1998) (arguing that personhood interests can be used to justify intellectual property rights). ↑

- . See generally Abraham Drassinower, What’s Wrong with Copying? (2015) (arguing that copyright law is justified “as an affirmation of the author’s autonomy as a speaking being.”); Laura Biron, Public Reason, Communication and Intellectual Property, in New Frontiers in the Philosophy of Intellectual Property (Annabelle Lever ed., 2012) 225 (stressing the “need for copyright scholars to focus on the true relevance of Kantian autonomy”); Anne Barron, Kant, Copyright and Communicative Freedom, 31 Law & Phil. 1 (2012) (applying Kant’s theory of moral autonomy to copyright law). ↑

- . See generally Neil Weinstock Netanel, Copyright and a Democratic Civil Society, 106 Yale L.J. 283 (1996) (arguing that copyright law’s fundamental role is supporting democratic institutions). ↑

- . See Robert P. Merges, Justifying Intellectual Property 3 (2011) (noting the lack of “verifiable data showing that people are better off with IP law than they would be without it.”); Mark A. Lemley, Faith-Based Intellectual Property, 62 UCLA L. Rev. 1328, 1338 (2015) (criticizing those who respond to this lack of empirical economic data by retreating from utilitarian theories of IP to a “new religion” of faith-based theories that treat “IP as an end in itself”). ↑

- . See Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Isaac McPherson (Aug. 13, 1813), https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-06-02-0322 [https://perma.cc/3FAC-F4KE] (criticizing the theory that “inventors have a natural and exclusive right to their inventions”). ↑

- . See Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia 174–75 (1974) (“But why isn’t mixing what I own with what I don’t own a way of losing what I own rather than a way of gaining what I don’t?”); Jeremy Waldron, From Authors to Copiers: Individual Rights and Social Values in Intellectual Property, 68 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 841, 879–80 (1993) (arguing that “modern law shatters the connection between author and work,” which undermines Lockean arguments that authors should own what they produce); Patrick R Goold, Intellectual Property’s Faith-Based Empiricism, 25 Green Bag 289, 294 (2022) (questioning the assumption that “joining something [a person] owns to something he does not own give[s] him ownership of the combined outcome?”); see generally Seana Valentine Shiffrin, Lockean Arguments for Private Intellectual Property, in New Essays in the Legal and Political Theory of Property 138 (Stephen R. Munzer ed., 2001) (challenging “the claim that Lockean foundations straightforwardly support most strong natural rights over intellectual works”). ↑

- . See generally Oren Bracha & Talha Syed, Beyond Efficiency: Consequence-Sensitive Theories of Copyright, 29 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 229 (2014) (describing the similar weaknesses between efficiency and democratic theories, while providing arguments to overcome the trade-off). ↑

- . Cf. David A. Simon, Copyright’s Missing Personality, Hous. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2025) (manuscript at 36–38) (exploring the theoretical weaknesses in personality justifications of copyright law but acknowledging that a “personality-based justification on a deflated version of personality is possible”). ↑

- . See Mala Chatterjee, Presentation at the University of Cambridge (draft on file with author). For that matter, why does investing one’s personality in a work justify control of anything else? See generally Simon, supra note 11 (questioning whether a moral rights theory of copyright law can properly be based on the concept of personality). But see sources cited supra note 4 (arguing in favor of a personality-based justification of copyright). ↑

- . The European patent abolitionist movement of the nineteenth century provides a good example of such arguments. See generally Mark D. Janis, Patent Abolitionism, 17 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 899 (2002) (recounting the history of the nineteenth-century patent abolitionism movement in Britain and drawing similarities to the modern U.S. patent reform debate); Stef van Gompel, Patent Abolition: A Real-Life Historical Case Study, 34 Am. U. Int’l L. Rev. 877 (2019) (explaining the circumstances that led to the abolition of patents in the Netherlands in 1869). Fewer make this argument today, although some come close. See generally James Bessen & Michael J. Meurer, Patent Failure: How Judges, Bureaucrats, and Lawyers Put Innovators at Risk (2008) (highlighting the failures of the American patent system and raising doubts about proposed reforms); Michele Boldrin & David D. Levine, Against Intellectual Monopoly (2008) (arguing that “intellectual property is an unnecessary evil”). ↑

- . See Patrick R. Goold, Intellectual Property Absurdism or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love IP, 87 Mod. L. Rev. 761, 779–84 (2024) (exploring the “absurdity of loving IP” despite its “dubious normative foundations”). ↑

- . In this Essay, the term pluralism relates only to the justification of a particular legal regime. It does not refer to “innovation policy pluralism,” which conceives of IP as one of many tools that could be used to promote a country’s innovative output. See generally, e.g., Daniel J. Hemel & Lisa Larrimore Ouellette, Innovation Policy Pluralism, 128 Yale L.J. 544 (2019) (arguing that “pluralism,” or the combination of IP and non-IP policies, “provides a more descriptively accurate account of the innovation policy landscape than those that dominate the existing literature.”); Michael J. Burstein, Toward Pluralism in United States Intellectual Property, in Improving Intellectual Property: A Global Project 484 (2023) (articulating and defending “a vision of IP pluralism . . . that recognizes that IP and non-IP innovation incentives can and should exist side-by-side”). Nor does it refer to “international IP pluralism,” which is concerned with whether different countries should enjoy flexibility to derogate from international IP norms for their own socio-economic policy reasons. See generally, e.g., Is Intellectual Property Pluralism Functional? (Susy Frankel ed., 2019) (presenting diverse international perspectives on the “challenges and opportunities of pluralism in intellectual property.”). ↑

- . See generally, e.g., Hanoch Dagan, Autonomy, Pluralism, and Contract Law Theory, 76 Law & Contemp. Probs. 19 (2013) (advocating for a structurally pluralist theory of contract law); see also Hanoch Dagan & Michael Heller, The Choice Theory of Contracts 7 (2017) (noting contract law theory’s “familiar, autonomy-based commitment to pluralism.”); Nathan Oman, Unity and Pluralism in Contract Law, 103 Mich. L. Rev. 1483, 1488–503 (2005) (book review) (presenting a theory of “principled pluralism” in contract law). ↑

- . See infra Part III. ↑

- . We are not concerned in this paper with justifying law as such or explaining what law is—the domain of jurisprudence. ↑

- . See generally, e.g., Morton J. Horwitz, The Transformation of American Law 1870–1960: The Crisis of Legal Orthodoxy (1992) (tracing the historical struggle between two theoretical foundations to explain how American law has developed over the years). ↑

- . See generally Ronald Dworkin, Law’s Empire (1986) (presenting an interpretive analysis of the law). ↑

- . See Richard A. Posner, Economic Analysis of Law 6 (1972) (explaining that the common law “bear[s] the stamp of economic reasoning.”); Paul H. Rubin, Why Is the Common Law Efficient?, 6 J. Legal Stud. 51, 53–57 (1977) (providing an alternative explanation for how the common law has evolved towards efficiency); see generally Richard A. Posner, Utilitarianism, Economics, and Legal Theory, 8 J. Legal Stud. 103 (1979) (responding to critics of using economic theory to explain the common law). ↑

- . The normative view was most persuasively articulated by Guido Calabresi in The Costs of Accidents, which he published two years before Posner’s Economic Analysis of Law. See generally Guido Calabresi, The Costs of Accidents: A Legal and Economic Analysis (1970) (providing a normative analysis for why accident law ought to be efficient). ↑

- . Ronald M. Dworkin, Is Wealth a Value?, 9 J. Legal Stud. 191, 196 (1980). ↑

- . See generally Dworkin, supra note 20 (providing an interpretive analysis of the law). ↑

- . See generally Patrick R. Goold, Unbundling the “Tort” of Copyright Infringement, 102 Va. L. Rev. 1833 (2016) (explaining that “copyright protects multiple interests from different types of injury”); David Fagundes, The Plural Tort Structure of Copyright Law, Jotwell (Aug. 4, 2016), https://ip.jotwell.com/the-plural-tort-structure-of-copyright-law/ [https://perma.cc/N6AP-5D35] (reviewing Goold’s article); see also Wendy J. Gordon, Copyright Owners’ Putative Interests in Privacy, Reputation, and Control: A Reply to Goold, 103 Va. L. Rev. Online 36, 41 (2017) (critiquing Goold’s article while acknowledging that various interests underlie copyright law). ↑

- . See generally, e.g., Bracha & Syed, supra note 10 (evaluating consequence-sensitive theories of copyright that adopt plural values). ↑

- . Aditi Bagchi, Pluralism, in Research Handbook on the Philosophy of Contract Law (Mindy Chen-Wishart & Prince Saprai eds., 2025) (forthcoming Apr. 2025) (manuscript at

2–3). ↑ - . Id. at 2. ↑

- . Id. at 11. ↑

- . Id. at 12. ↑

- . Id. at 3. ↑

- . See John Rawls, A Theory of Justice 340 (rev. ed. 1999) (referring to the notion that “considerable differences in citizens’ conceptions of justice” can lead to “similar political judgments.”). ↑

- . See id. at 340–42 (explaining how “overlapping consensus” makes civil disobedience the “reasonable and prudent form of political dissent” in democracies). ↑

- . D.B. Resnik, A Pluralistic Account of Intellectual Property, 46 J. Bus. Ethics 319, 319 (2003). ↑

- . Id. at 324. ↑

- . Id. at 325. ↑

- . Id. at 322–23. ↑

- . See id. at 331 (explaining, for example, that “utility should have the highest priority in disputes about patents,” whereas “utility should have a much lower priority in disputes about privacy”). ↑

- . Id. at 330. ↑

- . Id. at 330–31. ↑

- . Id. at 331. ↑

- . Michael Edward Kenneally, Intellectual Property Rights and Institutions: A Pluralist Account 14 (May 5, 2014) (Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University) (ProQuest). ↑

- . Id. at 15. ↑

- . Id. at 183. ↑

- . Id. at 14. ↑

- . See id. at 17, 37 (analyzing the “Lockean right against interference with labor” and what qualifies as “wrongful interference”). ↑

- . See Nozick, supra note 9, at 174 (critiquing the Lockean argument based on mixing labor); Waldron, supra note 9, at 879–80 (same); see also Kenneally, supra note 42, at 23 (acknowledging Nozick and Waldron’s critiques). ↑

- . Id. at 25. ↑

- . Id. at 52–53. Kenneally claims, for example, that if A replicates a cart made by B, and A sells the replicas, she has not interfered wrongfully with B’s property. If one’s intended consequences are to have people purchase carts, then A is disrupting those consequences. Those intentions, however, are not reasonable or justified unless IP exists. If this analysis is correct, IP’s subject matter makes it ill-equipped for justification under Locke’s theory. See id. at 53–54. Kenneally acknowledges that IP itself may shape these expectations if implemented. See id. at 176–77 (stating that IP law provides “an additional opportunity for material gain beyond what is found in the state of nature.”). ↑

- . Id. at 53–55. ↑

- . See id. at 101–06 (analyzing Kant’s view on natural rights and agreeing that the rights of attribution and release are justified by autonomy interests). ↑

- . Id. at 183. ↑

- . Id. at 110. ↑

- . See id. at 126–29 (arguing that “whether one [IP institution] makes a person better off than another may be indeterminate.”). ↑

- . See id. at 131–32 (“The essential point is that the heterogeneity of the pleasurable feelings that alternative sets of copyrightable works would produce . . . not infrequently makes it hard to believe one bundle [is] better [sic] overall than an alternative.”). ↑

- . Id. at 143–45. ↑

- . Id. at 143–44. ↑

- . Id. at 145. ↑

- . Id. at 146. ↑

- . Id. at 183. ↑

- . Merges, supra note 7, at 14. ↑

- . Id. at 13. ↑

- . Id. at 10. ↑

- . See id. at 16 (paralleling “actual institutions and social practices” to “the practical”). ↑

- . Id. at 10. ↑

- . See Justin Koo, A Justificatory Pluralist Toolbox: Constructing a Modern Approach to Justifying Copyright Law, 42 Eur. Intell. Prop. Rev. 469, 479–80 (2020) (explaining that a pluralist justification for copyright law is attractive given the competing interests of various individuals). Koo’s argument is specific to copyright, but it could easily be adapted to patent law. ↑

- . See id. at 470–74 (arguing that the traditional justifications of copyright—Lockean labor theory, Hegelian personality theory, and utilitarianism—are “ill suited to the modern context.”). ↑

- . Id. at 474. ↑

- . Id. at 477. ↑

- . Id. at 479–80. ↑

- . Id. at 477. ↑

- . Later in this Part we show that some of these objections apply to other pluralists as well. ↑

- . Resnik, supra note 34, at 324. ↑

- . Merges, supra note 7, at 3. ↑

- . See, e.g., Arnold Plant, The Economic Theory Concerning Patents for Inventions, 1 Economica 30, 39–40 (1934) (exposing holes in the utilitarian assumption that patents are responsible for innovation); Fritz Machlup, Subcomm. on Pats., Trademarks, and Copyrights, 85th Cong., An Economic Review of the Patent System 77–79 (1958) (concluding that “[n]one of the empirical evidence . . . either confirms or confutes the belief that” patents promote innovation and productivity); Stephen Breyer, The Uneasy Case for Copyright: A Study of Copyright in Books, Photocopies, and Computer Programs, 84 Harv. L. Rev. 281, 322 (1970) (agreeing with Machlup’s conclusion); K.J. Arrow, Economic Welfare and the Allocation of Resources for Invention, in 2 Readings in Industrial Economics: Private Enterprise and State Intervention 219, 220, 227–30 (Charles K. Rowley ed., 1972) (“It is shown that all three of the reasons given above for a failure of the competitive system to achieve an optimal resource allocation hold in the case of invention.”); George L. Priest, What Economists Can Tell Lawyers about Intellectual Property: Comment on Cheung, 8 Rsch. L. & Econ. 19, 19–21 (1986) (admitting that “economists know almost nothing about the effect on social welfare of the patent system or [other IP systems].”); Josh Lerner, The Empirical Impact of Intellectual Property Rights on Innovation: Puzzles and Clues, Am. Econ. Rev., May 2009, at 343, 347 (finding a “lack of a positive impact of strengthening of patent protection on innovation”); Adam B. Jaffe & Josh Lerner, Innovation and Its Discontents: How Our Broken Patent System Is Endangering Innovation and Progress, and What to Do about It 8–9, 13–18 (2004) (exploring how the current patent system creates inefficient incentives); James Bessen & Michael J. Meurer, Patent Failure: How Judges, Bureaucrats, and Lawyers Put Innovators at Risk 84–88, 92–93 (2008) (concluding that the “empirical evidence . . . strongly rejects” the argument that “patents universally spur innovation and economic growth”); Michele Boldrin & David K. Levine, The Case Against Patents, 27 J. Econ. Persp. 3, 4–7 (2013) (explaining that studies show little to no evidence linking patents to innovation or productivity); see also Stuart J.H. Graham, Robert P. Merges, Pam Samuelson & Ted Sichelman, High Technology Entrepreneurs and the Patent System: Results of the 2008 Berkeley Patent Survey, 24 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 1255, 1283 (2009) (“[I]n general, the technology startup executives responding to our survey report that patents offer relatively mixed to weak incentives to engage in innovation.”). ↑

- . Cf. Patrick Goold & David A. Simon, On Copyright Utilitarianism, 99 Ind. L.J. 721, 767–68 (2024) (defending a specific form of utilitarian justification for copyright despite “our current inability to measure copyright’s utility”). ↑

- . Resnik argues that his approach is preferable because it is practically workable, unlike utilitarian theories, because it allows the decision-maker to “balanc[e]” the values of justice, autonomy, and utility against one another “in light of the facts and circumstances of the case.” Resnik, supra note 34, at 332. But this balancing seems at least as hard as measuring utility and no less predictable or reliable. ↑

- . Id. at 330–31. ↑

- . See, e.g., Gordon, supra note 25, at 45–47 (arguing that “doctrinal development, demands of internal consistency, and copyright policy” indicate that privacy is not a legitimate copyright concern). ↑

- . See, e.g., Joseph Raz, On the Nature of Rights, 93 Mind 194, 208 (1984) (describing the difference between rights and interests, which suggests that not all interests support rights). ↑

- . The argument for legitimate political interests is distinct from the argument for a justification of a legal regime, institution, or right. ↑

- . Kenneally also references the philosophical example of Buridan’s Ass and makes the same conclusion. Kenneally, supra note 42, at 144. ↑

- . We could, for example, decide not to cut the cake and let people use their hands or forks to eat it. The example itself is also rigged in favor of the result because cutting cake seems to have a non-controversial built-in justification. But many decisions about what to do cannot reach the stage of equally plausible choices without first engaging in a winner-take-all battle. ↑

- . At times, Kenneally seems to gesture at this, including in his discussion of parody, mentioned above. See id. at 147 (suggesting that fair use doctrine is justifiable because the alternative would be “insufficiently attentive” to parodists’ and society’s interests). ↑

- . Even here, however, the structure of the rules must eventually bottom out in something measurable. IP incentives must still ensure the “availability of new inventions and creative works.” Id. at 183. ↑

- . Merges in some sense attempts to reconcile competing normative foundations by reference to consistent principles in doctrine. This is a variant of the “convergence strategy.” See Jody S. Kraus, Reconciling Autonomy and Efficiency in Contract Law: The Vertical Integration Strategy, 11 Phil. Issues 420, 420–21 (2001) (“[Convergence strategy] attempts to demonstrate that efficiency and autonomy contract theories happily converge in their normative assessment of most contract doctrines, even though they do so on logically incompatible grounds.”). On whether he is successful, see generally David H. Blankfein-Tabachnick, Intellectual Property Doctrine and Midlevel Principles, 101 Calif. L. Rev. 1315 (2013). ↑

- . See Rawls, supra note 32, at 171 (explaining that the “principles of justice” define a “workable political conception” that justifies constitutional democracies). ↑

- . Koo, supra note 66, at 474. ↑

- . See id. at 474 (expressing the need for an approach that “accounts for all of [copyright’s] nuances, diverse interests and stakeholders and competing considerations.”). ↑

- . Id. at 477. ↑

- . See generally Goold, supra note 9 (arguing that “empirical arguments in IP . . . are not rational.”); Lemley, supra note 7 (exposing the irrationality of “trusting in theory” when the empirical evidence is ambiguous at best). ↑

- . See Harold Demsetz, Toward a Theory of Property Rights, Am. Econ. Rev., May 1967, at 347, 348–49, 356 (explaining how property rights guide incentives toward efficient use of resources); Margaret Jane Radin, Property and Personhood, 34 Stan. L. Rev. 957, 957 (1982) (arguing that property rights provide individuals with the “control over resources in the external environment” necessary for “proper self-development”). ↑

- . See Richard Posner, A Theory of Negligence, 1 J. Legal Stud. 29, 31–33 (1972) (positing that “the dominant function of the fault system” is to create rules that will generate the most efficient level of accidents and safety); see generally John C.P. Goldberg & Benjamin C. Zipursky, Recognizing Wrongs (2020) (asserting that tort law is generally designed around the idea of “a victim’s right to redress as against a wrongdoer”). ↑

- . See Oren Bracha & Talha Syed, A Law and Economy of Intellectual Property, 103 Texas L. Rev. (forthcoming 2025) (manuscript at 31–32) (outlining the expansion of IP rights). ↑

- . See, e.g., Peter S. Menell, Mark A. Lemley, Robert P. Merges & Shyamkrishna Balganesh, Intellectual Property in the New Technological Age 2 (2023) (including trade secret and trademark in “the principal modes of intellectual property protection”). ↑

- . Id. at 936, 1047 (describing the expansion of trademark law and the “broad range of liability concepts” it now encompasses). ↑

- . See, e.g., Resnik, supra note 34, at 319 (arguing that “a pluralistic approach provides the best account for IP” in part because “there are many different types of IP”). ↑

- . Bracha & Syed, supra note 94, at 3. ↑

- . Id. ↑