Seeing the Dead: Marks, Meaning and the Haunting of American Trademark Law

[Introduction]

The retirement of trademarks such as “Uncle Ben” and “Aunt Jemima” during the fulcrum of the Black Lives Matter movement prompted scholars to reconsider how trademark law protected various marks that perpetuated images built on a terrifying scaffold of racist imagery.[1] In many ways, though, this reckoning stopped without a full accounting of trademark’s fraught relationship with social identities of race and caste in the United States.

Indeed, if we simply sit with the vocabulary of trademarks, we can see the ghosted remnants of trademark law’s relationship with enslavement. We “brand” ourselves as enslaved people were “branded” by an iron.[2] We “pass off” the goods of another as a person could “pass” from one race to another.[3] We “register” a mark today as enslaved people then received a new name and had their new name “registered” on a ship register.[4]

The “haunting” of trademark law, though, does not rise simply from the remnants of an older order glimpsed through this vocabulary. What we understand as trademark law was formed in the fulcrum of what I term the “enslavement economy,”[5] which describes the political, economic, and social order produced by the process of enslavement imposed throughout the Atlantic World.[6] As Roberto Saba notes:

Slave labor was central to the making of the modern world. It gave Europeans the means to occupy and develop the Americas. The trade in slaves helped merchants accumulate capital that was reinvested in agriculture, industry, and infrastructure. Slave plantations produced the sugar, cotton, and coffee that propelled the industrial revolution in the North Atlantic countries.[7]

Trademark law is an ideal place to consider the relationship of intellectual property to the political, social, and economic system of enslavement. Trademarks, which protect the commercial signs associated with the goods and services of its users, seem to be intimately connected to the economic practices of enslavement, either because a slave market would advertise its services in selling enslaved individuals using trade names[8] or because goods like sugar or cotton produced by enslaved persons would be trademarked.[9]

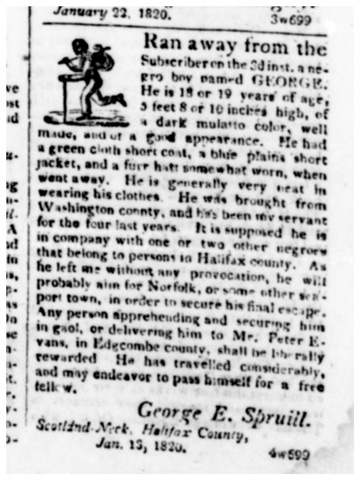

I use fugitive slave advertisements—advertisements placed in colonial and antebellum newspapers that sought the return of an enslaved person to their enslaver—to explore the relationship of trademark law and the construction of race and caste in the United States. Fugitive slave advertisements[10] are understood to be a crucial part of the social,[11] cultural,[12] and economic history of enslavement.[13] Figure 1 depicts an example of a fugitive slave advertisement placed by George Spruill in the Edenton Gazette and the North Carolina General Advertiser, in Halifax, North Carolina in 1820, seeking the return of George, an 18- or 19-year-old enslaved person.[14]

Figure 1

This advertisement[15] contains hallmarks of the fugitive slave advertisement: a stylized picture of an escaping individual, a description of the individual, and indeed, a claim that the individual sought to “pass himself for a free fellow.”[16]

This Essay adds to a substantial, interdisciplinary literature on fugitive slave advertisements. Uniquely, I read them as though they are a legal source, much like a legal opinion.[17] Jonathan Bush has identified what remains a significant problem in the study of the law of enslavement, that is, its reliance on the public law embodied in criminal law, rather than through private mechanisms, such as tort and contract law.[18] Overlooking these private law mechanisms results in a paucity of legal opinions. This paucity of legal source is intensified because the law of England did not offer sufficient analogues to the experience of Atlantic slavery,[19] thus making it difficult to incorporate into pre-existing legal doctrines.

Bush’s critique of “sourcing” the law of enslavement could extend to the specific development of trademark law as well. Indeed, as early as 1925, Frank Schechter identified a key problem in understanding the development of trademark law: that it is difficult “to . . . determine[] the actual point of contact between the fragmentary law of trade-marks as developed in the guilds and the modern common law and equitable doctrines of trade-mark law.”[20] Fugitive slave advertisements are also useful for a practical reason: they are now more accessible given recent efforts to successfully digitize these advertisements. In this Essay, I will be relying on two databases, the North Carolina Runaway Slave Notices Project, which has fully digitized images associated with fugitive slave advertisements,[21] and the Freedom on the Move Project, which has crowdsourced information about more than 33,000 fugitive slave advertisements (although its images are not transferable from the website).[22]

Fugitive slave advertisements offer us one way to explore how the legal framework of both enslavement and trademark law were created, in light of the sparseness of “official” texts like legal opinions or statutes during the colonial and antebellum period. In this Essay, I use fugitive slave advertisements to examine how “the haunting of trademark law” helps us comprehend two fundamental elements of the legal history of trademark law. First, in Part I, I explore how trademarks operate as both information forms and information systems in the construction of the social process of market exchange. Second, in Part II, I explore how the informational content of the fugitive slave advertisement helps us to retrieve the “ghost texts” and the “haunted texts” of trademark law. In highlighting the historical methods associated with Atlantic history and diasporic studies, I explore how the fugitive slave advertisements and enslavement economy visualized the status marks that sought to bridge local, regional, and national slave markets in the colonial and antebellum United States.

[“Haunt: Habit, wont, custom, usage”][23]

Ironically, the earliest use of the term “haunt” has a meaning connected to trademark law: a haunt was a place that a person used.[24] Of course, the pragmatic justification of trademark is its use in commerce.[25]

Part I of this Essay ties the trademark intellectual property law to a broad interdisciplinary field of information theory.[26] In my previous work on this subject, I made two interlocking claims about the relationship of information theory and intellectual property as a discrete sub-field. First, adopting Michael Buckland’s definition of information as a “thing” that conveys information,[27] I outlined what can constitute a “thing” as either an information form—that is, a tangible or intangible object or site—or an information system—a system of social relations “built around an information object that is produced by and link[s] together specific social actors within a specific social system.”[28] Second, I examined the way that the law “culls” a broad universe of information through the act of instantiation (deciding what information receives protection), the action of relation (deciding how to foster the discursive relationships within particular social systems), and the act of meaning (deciding to assign authoritative meaning to protect information forms and systems).[29]

A singular trademark—like other informational forms—is experienced as an informational object in an intangible form.[30] A singular trademark, by itself, can disclose information. J. Shahar Dillbary notes that a singular trademark placed on a consumer good can convey two types of information:

First, [trademarks] provide consumers with information that helps them identify and choose the product they want to purchase from a set of competing products. Trademarks serve this inter-brand function by giving a product a name (its trademark) which denotes to the public a single source of sale or manufacture.

. . . .

Second, trademarks often provide information about the product itself (intra-brand information).[31]

To add to this complexity, the meaning of the singular trademark can also be experienced in other modalities. The meaning of the trademark can be amplified because we experience it as an informational object in a tangible, physical environment (i.e., as a specific sign placed on a tangible object like a shoe or within a specific location such as a mall).[32] I refer to this process as materiality, a lawmaking process that helps us to distinguish between an intangible object and an object located in a physical site.[33] Materiality functions to protect different modalities between the object and site and to “manage the relationship between an actual physical space, place and community, and its abstracted, legally protected information form.”[34] Mark Lemley and Mark McKenna have explored what they term “trademark spaces”: The ways in which a trademark examiner approaches an item as either a product configuration or a product design (such as trade dress or packaging) often work as trademark’s secret step zero, “a preliminary framing function, determining whether courts recognize the features as trade dress that therefore must be categorized as product design or as packaging.”[35] I add to Lemley and McKenna’s insight by stressing that these “trademark spaces” work to create meaning in the mark by “materializing” in the informational form of the trademark.

In addition to the trademark’s status as an informational object, that same trademark is also part of larger information systems that build larger meanings associated with the informational object. Frank Schechter’s lasting insight as a trademark historian was in his methodological insight that the “germs of our modern trademark” lay in the “great mass of records of the organizations of merchants and craftsmen themselves.”[36] Trademark law, consequently, is tied to what I have identified in my work as “sociality” of information.[37] The sociality of information refers to the ways in which “information is deeply embedded in the cultural, political, and social environment of a temporally bound community.”[38] Trademark law itself intersects specifically with what sociologists Neil Fligstein and Luke Dauter identify as:

[O]ne kind of social exchange, that of markets, and to the structuring of that kind of social exchange, under the conditions we call capitalist. This focus includes the study of firms, product markets, and labor markets as well as their broader linkages to suppliers, workers, and states and the role of local cultures (i.e., local in the sense of belonging to a particular market), systems of meanings insofar as they influence what products are, and the role of morality in the generation of particular kinds of markets.[39]

Trademark law reflects this sociality of the market in two ways. First, trademark law protects how different communities speak, what Laura Heymann has identified as the naming functions that manage the relationships between the actors within a particular commodity market.[40] These naming functions can become a code for the community of competitors. Hannah Farber has suggested that within commercial contexts during the colonial era:

In order for marks to function, there had to be widespread agreement about the codes used to interpret them. The history of marks thus shows us how collaboration and even consensus was a prerequisite for individualistic profit-seeking behavior. We can here conceive of at least two different communities: the narrower group that generated codes (e.g., cask-makers, legislators) and the broader one made up of those who were capable of reading marks according to the appropriate code. Thus the study of marks, which were entirely capable of crossing imperial boundaries, offers us new ways of understanding the contours of Atlantic commercial space. A study of “Anglo-American” marks would not necessarily be broad enough.[41]

Seeing the trademark in its informational form and as an information system provides a way to track how “meaning” in marks is built over time and scale: that is, a mark is a historically contingent form of information that can change over time. In a descriptive sense, trademark law engages with this issue all the time; for instance, a mark can start off as a way to describe a discrete product within a narrow geographic location (e.g., the use of the term “sake” in Japan) but then change meaning as the product moves into another market (e.g., the use of the term “sake” in the United States).[42]

In a normative sense, trademarks themselves are signals of, or are embedded in, markets of exchange that themselves change over time. Martin Bruegel has examined how the market in rural communities changed in the antebellum United States, contending that what we understand as “market society” and “market culture” develops over time.[43] He notes: “Rather than relying on the market as a heuristic theory concerning abstract functions and unchanging . . . individuals,” it is better to examine “the emergence of a market society and culture as the genesis of social rules and conventions that were themselves the result of struggles, hesitations, and compromises among historical actors.”[44]

The struggle to build meaning in a mark is difficult because the materialization of information objects and sites is contingent, shaped, for example, by a shift in methods of capital accumulation[45] or by a shift in how we view the political salience of a mark.[46] We see trademarks as information objects operating simultaneously in many different modalities: as a mark on a paper or good that needs to be read by a consumer or a competitor or as a sign on a store at the mall. Trademarks of many kinds existed in the enslavement economy. A trademark could be on a good; a significant example of this are trademarks placed on cotton goods sold by textile manufacturers in England.[47] A trademark could also reflect its status as an information system in an enslavement economy. For instance, as Hannah Farber explains, “the panoply of marks made on slaves allows us to trace the political geographies of the Atlantic slave trade” through the different marks on enslaved persons, which could reveal the origins of enslaved persons or mark where they were sent.[48] Farber notes, for instance:

The South Sea Company branded slaves with the name of the American port to which they were bound, while in Guinea slaves received the mark of the local factor . . . . These marks revealed the overlapping spheres of authority that impinged on the enslaved person: dealer and owner, vessel and port, sovereign, corporation, the church. Each of these was part of the code.[49]

[“A Spirit Supposed to Haunt a Place: A Ghost”][50]

The collective text of fugitive slave advertisements helps to center us on how trademarks function as information objects and information systems, by providing us with a substantial dataset that changes over time. However, fugitive slave advertisements are not ideal historical sources; for instance, the text of fugitive slave advertisements often reflected the bias of those who drafted the text since the genre operated as “an address from a white slaveholder to a (usually) white audience aimed at the practical goal of identifying and apprehending a particular individual.”[51]

As legal sources, fugitive slave advertisements have flaws as well. Fugitive slave advertisements—unlike legal opinions—are not directed towards standard legal actors like lawyers or legislators, nor do they attempt to explain the law to an expert or even a lay audience. Their utility as legal sources primarily emerge from their ability to convey details of the mechanisms of the law of enslavement such as the fact that return of fugitive slaves would often take place at the local jail,[52] or when directed specifically to trademark law, that enslaved individuals could be branded or marked by their owner.[53]

Moreover, any study of fugitive slave advertisements must contend with silence and erasures; indeed, Saidiya A. Hartman encourages us to “read them against the grain in order to write a different account of the past, while realizing the limits imposed by employing these sources, the impossibility of fully recovering the experience of the enslaved and the emancipated, and the risk of reinforcing the authority of these documents.”[54] To help us to explore the relationship of the enslaved economy to trademark law, we should read the fugitive slave advertisements to see whom and what has been erased or silenced. Fugitive slave advertisements help us to see through what I term the “ghost text” and the “haunted text.” The ghost text shows us the wide world of marks that composed the visual landscape of the enslavement economy. The haunted text reinforces the way in which trademarks and brands reinforced the dispossession and caste status of enslaved individuals.

My comparison of the ghost text and the haunted text draws on hauntology, the literary study of haunting.[55] Colin Davis, in reviewing the work of French literary theorists, tells us that two types of ghost stories exist: the spectre and the phantom.[56] The spectre, a concept derived from the political theory of Jacques Derrida, haunts us because of something in the text that is buried or going unacknowledged within the terms of the text.[57] Consequently, Colin Davis notes that “Derrida calls on us to endeavour to speak and listen to the spectre, despite the reluctance inherited from our intellectual traditions.”[58] The ghost texts of the fugitive slave advertisements, then, help us to uncover the ways in which the development of trademark law is implicated in the enslavement economy.

By contrast, the phantom, which Colin Davis describes as a concept derived from the psychoanalytical framework of Nicolas Abraham and Maria Torok, does not deliver information that frees us to see or acknowledge a hidden presence.[59] Rather, the phantom is a ghost story that results from an intergenerational trauma; the ghost comes not to “return from the dead in order to reveal something hidden or forgotten, to right a wrong or to deliver a message that might otherwise have gone unheeded,” but to express the “encrypted, unspeakable secrets of past generations.”[60] The haunted text speaks to trademark law’s relationship to terror and caste, what Christopher Parsons Wolcott, the Attorney General of Ohio, referred to as “another incident” of slave ownership—the ability of a slave owner “to brand the slave or slit his ears to mark him as his property.”[61] The haunted text’s legacy speaks to an idea that we do not often confront in intellectual property: Sometimes, by rather simply serving a creative incentive to inform to a consumer, an intellectual property good can foster real direct harm to an individual’s construction of identity.

What do the ghost texts of trademark law teach us about the development of trademark law in the United States? Runaway advertisements are windows into what I referred to as the materiality of legal information; that is, the runaway advertisements offer ways to comprehend the visual landscape of the enslaved economy. The visual landscape of the enslaved economy contains many different marks, some of which do not resemble what we would consider modern marks. For example, one type of mark that was referenced in runaway advertisements during the colonial era was referred to as the “country mark.”[62]

The country mark operated as a source identifier of origin, a mark that referenced the “place of origin, original names, patterns of scarification, and so on.”[63] Country marks could perform positive functions; Michael Gomez argues that they performed an important function in the formation of the identity of the Black political community in the United States.[64] Gomez notes that “[w]ithin the context of ethnicity and the formation of the African-based community, it is highly significant that not only Africans recognized their differences, but others did as well.”[65] Country marks could also reinforce an enslaved person’s status in the enslavement economy. Aldair Rodrigues, in his discussion of body marks in the colony of Brazil, noted that “[r]itual scars or other body marks were used to verify whether the inspected slave had been registered” in registers called livros de matricula that tracked whether a slave had been properly taxed or if a registered enslaved person escaped, died, or was sick.[66]

An example of a country mark was included in an advertisement contained within The New York Gazette and the Weekly in 1776:

TEN DOLLARS Reward. RUN-away last Thursday from the Subscriber, at Newark, a certain Negro Fellow named Jack, about 25 years old, a square well-built Fellow, pretty black, Guiney born, and spoke bad English: He took with him several Sorts of Cloths, his Master’s Gun, and a Grenadier’s Sword, with Brass Mountings: He is supposed to have had on a good Beaver Hat cocked in the Fashion, a light coloured fine Cloth jacket, without Sleeves, and may wear a Blanket Coat, he has a Scar right down his Forehead to his Nose, his country Mark, can handle a File, and understands the Brass Founder’s Business. Whoever takes up the said Fellow, and delivers him to Mrs. Wilkins, near Ogden’s Furnace, in Newark, shall have the above reward; or in New-York, to JACOB WILKINS.[67]

Jack’s country mark operates in three ways throughout the advertisement. First, the advertisement notes that he is “Guiney born,” thus indicating his “origin” within the text of the advertisement and operating like a designation of origin.[68] Second, Jack’s country mark operates as a way to identify the good: Jack himself.[69] And note the other marks used throughout the advertisement that do not have do with Jack at all: the term “Brass Founder’s Business” identifies the type of work that Jack was engaged in at the time of his escape and the term “Ogden’s Furnace” describes the location of a small business in Newark, New Jersey.[70] Jack’s fugitive acts speak to the complexity of naming in colonial America: Social actors spoke different languages (Jack speaks “bad English”) and had to navigate a world of status signals (Jack stole his Master’s Gun and had a “Beaver Hat cocked in the Fashion”).[71] The rich text of this fugitive slave advertisement opens a window into a trademark history—the history of small businesses that operated locally—that is not well understood in the relevant scholarly literature, which has focused on the operation of corporations.[72]

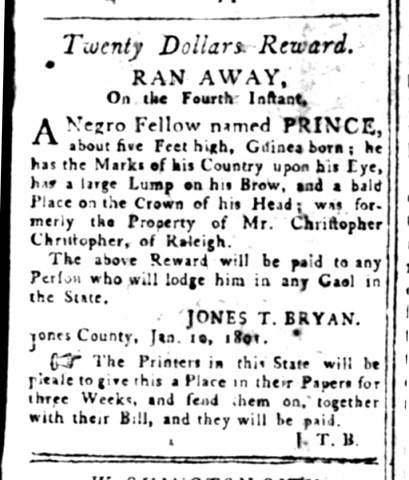

Seeing the country mark as a modern trademark can be difficult. At a practical level, it is hard to find a visual representation of a country mark itself. Fugitive slave advertisements were text-dependent and while, as I will discuss below, they contained stylized images of an enslaved person, a majority of these advertisements contained no visualized images. Rather, the majority of images were like the one depicted in Figure 2, which described the country mark in written form.[73]

Like the written advertisement for Jack, described above, the fugitive slave advertisement describes Prince’s country of origin (“Guinea born”) and describes “the Marks of his Country upon his Eye.”[74]

Like the written advertisement for Jack, described above, the fugitive slave advertisement describes Prince’s country of origin (“Guinea born”) and describes “the Marks of his Country upon his Eye.”[74]

Figure 2

What is also clear, though, is that our knowledge of country marks is limited in ways important for understanding the development of trademark law. The drafters of this advertisement knew its (white) readers would either know what a Guinea county mark looked like or at minimum could identify a country mark, if not that specific country mark; thus, they did not need to include a visual signifier as to what a mark looked like in the advertisement. Moreover, the lack of a visualized depiction of any country marks suggests the technological limits[75] of colonial and antebellum newspapers’ ability to depict multiple visual forms; a saturated trademark environment in which media could convey sophisticated visual information may have had to wait for a more sophisticated media culture that emerged in the late nineteenth century.

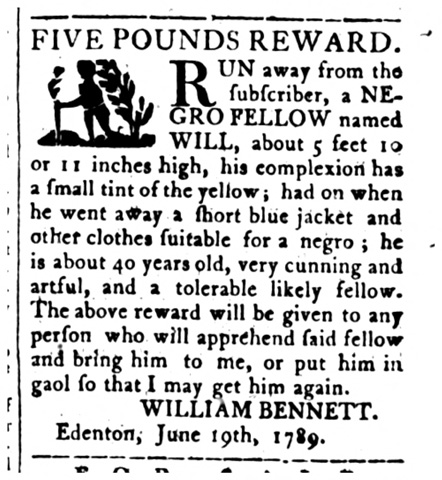

The ghost texts of fugitive slave advertisements help us understand how the American consumer was taught to read a mark connected to a text published in a type of media. We can see what we understand to be a modern trademark used on the page of the runaway advertisement itself, as a type of service mark employed by the newspaper. The advertisement depicted in Figure 2 is typical for the type of text-based fugitive slave advertisement. These depictions, however, began to change in the 1780s, as a stylized figure began to be used in the fugitive advertisement. For instance, beginning in 1789, the State Gazette of North Carolina began to use stylized images at the beginning of each ad to signal the beginning of the ad.[76] The image conveyed to the reader a way to identify the service offered by the newspaper. [77]

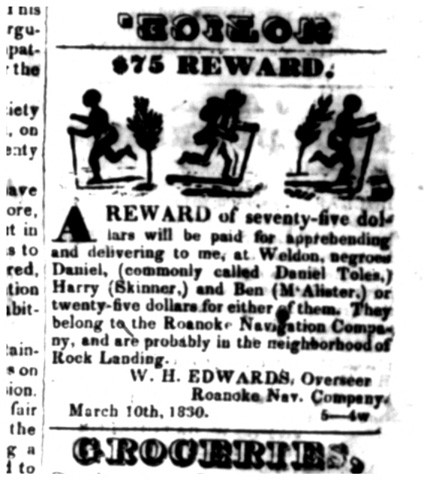

Although fugitive slave advertisements often remained text-based, by the 1830s, fugitive slave advertisements became more sophisticated. For instance, the fugitive slave advertisement outlined in Figure 4, [78] published in the Roanoke Advocate in 1830, contained three different visual images, three different types of fonts, and a visualized separation from other parts of the newspaper.[79]

Figure 4

Figure 3

These stylized images depicted in Figure 3 and Figure 4 performed two functions in the enslavement economy. As Marcus Wood notes, the juxtaposition of the stylized imagery with the more particularized details of individual fugitives operated as a type of “semiotic inertia” that lessened the humanity of enslaved people.[80] Equally important, however, from the standpoint of legal scholarship, these stylized images performed a different function: identifying to the consumer a “service” provided by the newspaper—the service of locating a fugitive slave.[81]

The other haunting of the American trademark law is tied to the haunted text, a text suffused with the legal subordination necessary to the enslavement economy. The haunted text differs from the ghost text because it forms a way to map trademark law’s relationship to what I have referred to in my other work as despotic information, which speaks to the reality that an “intellectual property good, like a copyright or trademark, can be implicated in systems of inequality, which can reinforce social identities, and promote discrimination and violence based on that social identity.”[82]

We can trace the haunted mark in two respects: the enslaved brand and the status brand. The enslaved brand speaks to the ability of the enslaver to physically mark or brand a slave. A basic search of the term “brand” on the Freedom on the Move database indicates that at least 665 advertisements of the 33,000+ advertisements recorded in the database contain the term.[83] For example, runaway advertisements included descriptions of brands such as “branded on the right breast IB,”[84] “branded on the shoulder in the West Indies with the letters G.M.K.,”[85] and “has lost her fore teeth, and has a small brand on her breast in the form of U.”[86] The brand functioned to serve as a visualized mark of an enforced caste status. Notably, within the ongoing discussion of whether we understand the origins of trademark as residing in competition law or property law, the existence of the enslaved brand suggests a darker origin story: the enslaved brand reinforced the commodified status of the branded person.

The status brand was another component of the enslavement economy that suggests an ongoing relationship between brands, marks, and the property economy. The status brand speaks to the state laws that prohibited certain categories of groups from engaging in the act of branding animals. A prototypical example of this type of statute is Sections 1–3 of the Cattle, Horses and Other Stock Act, which set forth the marking requirements in the state of Alabama in 1833.[87] Section 1 of the statute required every person in the state to have and register a brand and ear mark to cattle, horses and other stock, and further required that “no brand or mark similar to [an existing] brand or mark” could be recorded.[88] Section 2 of the Cattle, Horses and Other Stock Act then permitted disputes over the trademark to be resolved in front of the local justice of the peace.[89] Section 3 of the Cattle, Horses and Other Stock Act then required:

[N]o person whosever, shall send or permit any slave or Indian to go into any of the woods or ranges in the territory, to brand or mark any horse, mare, colt, mule, ass, cattle, hog, or sheep, under any pretence [sic] whatsoever, unless the said slave be in company, and under the direction of some reputable white person” and if the preceding act did occur the animal would be forfeited.[90]

Similar statutes were also enacted in Mississippi.[91]

The status brand demonstrates the connection of the act of branding to the preservation of caste status within the antebellum South. This speaks to the act of branding’s importance in maintaining social relationships within agricultural communities that were in the process of shifting modes of commodification. This status brand also indicates more complex informational origins of trademark law in the United States than is typically understood. The status brand indicates that intellectual property regimes were enmeshed in the enslavement economy and indeed worked to maintain the caste status of Native Americans and Blacks within American society. Notably, the existence of the status brand suggests a broader relationship between a public law of trademark and a public order of intellectual property law.

[Conclusion]

What does the haunting of American trademark law teach us? Initially, the ghost text speaks to what is very often absent in our understanding of the development of trademark law in the United States: its origins in, and relationship to, the system of enslavement that endured in the Atlantic World until Brazil abolished slavery and emancipated enslaved African communities in 1888.[92] I foreground how an enslavement economy built on visualized marks of status sought to bridge local, regional and national markets of enslavement. It seems to me the ghost text demonstrates how trademark law, given its ongoing relationship with other forms of commercial law, is an ideal place to consider the relationship of intellectual property and the political and economic system of enslavement. Trademarks—which protect the commercial signs associated with the goods and services of its users—is intimately connected to the economic practices of enslavement.

Likewise, the “haunting” of American trademark law by the haunted mark also widens the scope of our understanding of how trademark law developed in the United States by focusing on the ways in which trademark law was embedded in the public regulation of colonial and antebellum markets. For example, Mississippi’s 1822 An Act Concerning Strays and Drovers, Horses, Cattle, and Other Stock, and Directing Stock Brands and Marks to be Recorded not only designated who could engage in act of branding (“the act of status branding”) but also required “any horse, cattle or other stock” to have a “brand and ear mark different from the brand and ear mark of every other person in the same county,” “required ear mark and brand shall be recorded in the office of the clerk,” and resolved “any dispute shall arise respecting the brand or mark.”[93] Debates over the development of trademark law have typically focused on the private law of trademark by tracing its histories through tort actions between competitors.[94] However, the status brands suggest a public law of trademark,[95] where trademark law functioned as way to control the social meaning of visualized works. Further work in this area may help us to understand the consolidation of trademark law in the United States in the late nineteenth century.

To conclude, the ghost text and the haunted text offer us two ways to further understand the law of enslavement in the United States. First, regarding fugitive slave advertisements as legal sources offers us a way to trace the informal and formal mechanisms of a legal system dedicated to enslavement. Fugitive slave advertisements were written by enslavers (with the potential support of newspaper staff), and thus offer a way to map non-elite opinion on the status of enslaved persons within the colonial and antebellum United States. Runaway advertisements described enslaved individuals as property, reflecting common conceptions of legal statute.[96] Indeed, considered study of runaway slave advertisements can be seen as a sustained counternarrative to the types of legal narratives seen in the published opinions of elite judges.[97]

Second, both the ghost mark and haunted mark help us contemplate the relationship of intellectual property to broader values within a democratic society. The ghost text helps us to comprehend how the visual landscapes developed during the colonial and antebellum United States. Rebecca Houze describes the visual landscapes as a way to navigate a “built environment” in which “we encounter many images and objects, which are both strange and familiar. They are part of a shared language, a visual vocabulary of the collective imagination.”[98] Runaway slave advertisements allow us to “reconstruct” the visual landscapes of colonial and antebellum United States, which permits us to trace how modern commercial relations, and its accompanying signs, shaped the markets, farms, waterways, and plantations of the modern United States (and elsewhere). Understanding how the visual landscape of the United States developed, trademark law is situated to answer broader questions of political economy—that place where political and economic structures intertwine to produce social meaning in information. For example, seeing anew—the country mark—and the ways in which it served as both a mark of origin and a political identity helps us to understand how the modern trademark seeks to police self-identity.[99]

The haunted mark speaks to another dynamic within a political culture: the relationship of law to the political subordination of specific groups within a society. I have argued elsewhere that intellectual property law needs to engage and explore how it enforces social hierarchies of “race” or “gender” by “defining a status, by reinforcing a status, and by drawing boundaries between different statuses.”[100] Katrina H.B. Keefer refers to the branding of an enslaved person as simultaneously an “act of violence” that was also an “act of industry and capitalism” that allowed “slaveholders and slave traders to mark those they believed to be their property; it was a fundamental commodification of the human body.”[101] The enslaved brand was a central act of enslavement; it marked “a transition from human to commodity.”[102] The pervasive marking of the human bodies glimpsed in runaway slave advertisements defined the status of an enslaved person by providing a visible indicia of a subordination. The markings reinforced that status through the sheer horror of physically defiling the face or body of that person, ultimately offering a visualized boundary between a person and non-person, a citizen, and what Roger Taney referred to Black Americans in Dred Scott v. Sandford as mere “ordinary article[s] of merchandise.”[103]

- . See, e.g., Deborah R. Gerhardt, The Last Breakfast with Aunt Jemima and Its Impact on Trademark Theory, 45 Colum. J.L. & Arts 231, 232 (2022) (arguing that consumer investment theory offers a more powerful explanation about what is deserving of trademark protection than a law and economics perspective); Fady J.G. Aoun, The Belated Awakening of the Public Sphere to Racist Branding and Racist Stereotypes in Trademarks, 61 IDEA 545, 589, 625 (2021) (examining the emergence of Black and Indigenous counterpublics in the termination of racist trademarks); Jon J. Lee, Racism and Trademark Abandonment, 91 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 932, 938 (2023) (examining how trademark law may not permit the warehousing of formerly racist trademarks to prevent use in the marketplace). An earlier work in this area is Malte Hinrichsen, Racist Trademarks: Slavery, Orient, Colonialism & Commodity Culture (2012). ↑

- . See Jennifer M. Whitmer, You Are Your Brand: Self-Branding and the Marketization of Self, Socio. Compass, 2 (Jan. 21, 2019), https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12662 [https://perma.cc/W4YL-35EU] (“The popularization of self-branding as a mode of self-presentation is a product of a particular set of economic, social, and cultural influences which have led to the valorization of individualism, reflexivity, self-promotion, entrepreneurialism, and self-governance.”). ↑

- Elaine K. Ginsberg, Introduction: The Politics of Passing, in Passing and the Fictions of Identity 1, 2–3 (Elaine K. Ginsberg ed., 1996) (“The genealogy of the term passing in American history associates it with the discourse of racial difference . . . . As the term metaphorically implies, such an individual crossed or passed through a racial line or boundary—indeed trespassed—to assume a new identity . . . and access[] the [accompanying] privileges and status . . . .”). ↑

- . See, e.g., Henry B. Lovejoy, The Registers of Liberated Africans of the Havana Slave Trade Commission: Transcription Methodology and Statistical Analysis, 38 Afr. Econ. Hist. 107, 115–23 (2010) (examining the transcription method used by historians to examine naming practices on ships of enslavement); Richard Anderson, Alex Borucki, Daniel Domingues da Silva, David Eltis, Paul Lachance, Philip Misevich & Olatunji Ojo, Using African Names to Identify the Origins of Captives in the Transatlantic Slave Trade: Crowd-Sourcing and the Registers of Liberated Africans, 1808–1862, 40 Hist. in Afr. 165, 168–73 (2013) (examining the registers of enslaved individuals who were liberated after the closure of the slave trade in the British Empire). ↑

- . The term “enslavement economy” is drawn both from the political theory of racial capitalism, see, e.g., Jodi Melamed, Racial Capitalism, 1 Critical Ethnic Stud. 76, 76–77 (2015) (discussing the history and framework of racial capitalism) and the historical method of economic historians, see Trevon D. Logan, American Enslavement and the Recovery of Black Economic History, J. Econ. Persps., Spring 2022, at 81, 83–85 (examining the waves of economic history that have addressed the emergence of enslavement as a mechanism of capitalism). ↑

- . The term “Atlantic World” is drawn from the historical method, which explores the common political, economic, and social ties between North, Central, and South America. See Bernard Bailyn, The Idea of Atlantic History, 20 Itinerario, no. 1, 1996, at 19, 28–29 (contrasting the society of Atlantic civilization with that of the “old continent”); Benita Sampedro Vizcaya, Engaging the Atlantic: New Routes, New Responsibilities, 89 Bull. Hisp. Stud. 905, 910 (2012) (examining the expansion of Atlantic history to South and Central America); Alison Games, Atlantic History: Definitions, Challenges, and Opportunities, 111 Am. Hist. Rev. 741, 743–44 (2006) (examining three primary methods of Atlantic historical inquiry). ↑

- . Roberto Saba, American Mirror: The United States and Brazil in the Age of Emancipation 1 (2021). ↑

- . See Maurie D. McInnis, Mapping the Slave Trade in Richmond and New Orleans, Bldgs. & Landscapes, Fall 2013, at 102, 107 (describing the visual landscape of antebellum Richmond, including “storefronts and signs to advertise [slave traders’] businesses,” as evidence of their “participat[ion] in the modern urban commercial culture”). ↑

- . See John E. Crowley, Sugar Machines: Picturing Industrialized Slavery, 121 Am. Hist. Rev. 403, 427–28 (2016) (discussing the visual signs placed on hogshead barrels); see also Donica Belisle, Anti-Black Racism in Food Advertising: Rogers’ Golden Syrup and the Imagery of White Supremacy in the Canadian West, Gastronomica, Summer 2021, at 14–15 (examining the use of trademarks that depicted Black manual labor on sugar plantations by one company in Canada). ↑

- . Fugitive slave advertisements have been the subject of significant historical digitization efforts. See, e.g., Elizabeth Hopwood, Review, Freedom on the Move: A Digital Archive, 33 Eighteenth-Century Fiction 145, 146 (2020) (describing the design process and organization of the Freedom on the Move database). ↑

- . See, e.g., Jonathan Prude, To Look upon the “Lower Sort”: Runaway Ads and the Appearance of Unfree Laborers in America, 1750–1800, 78 J. Am. Hist. 124, 126 (1991) (examining the social conditions of appearance associated with working class individuals as described in runaway advertisements); Patricia Hunt-Hurst, “Round Homespun Coat & Pantaloons of the Same”: Slave Clothing as Reflected in Fugitive Slave Advertisements in Antebellum Georgia, 83 Ga. Hist. Q. 727, 730 (1999) (examining runaway advertisements to discuss the clothing options of enslaved individuals); Laura F. Edwards, Textiles: Popular Culture and the Law, 64 Buff. L. Rev. 193, 203–04 (2016) (examining the relationship between textiles and the legal acts of enslaved persons). ↑

- . David Waldstreicher, Reading the Runaways: Self-Fashioning, Print Culture, and Confidence in Slavery in the Eighteenth-Century Mid-Atlantic, 56 Wm. & Mary Q. (3d ser.) 243, 248–49 (1999) (examining the cultural position of slaves through runaway advertisements); Jordan E. Taylor, Enquire of the Printer: Newspaper Advertising and the Moral Economy of the North American Slave Trade, 1704–1807, 18 Early Am. Stud. 287, 290 (2020) (examining the relationship of eighteenth-century print culture to the proximity to enslavement and freedom in colonial America). ↑

- . Simon Middleton, Runaways, Rewards, and the Social History of Money, 15 Early Am. Stud. 617, 620 (2017) (examining the use of “rewards” for the return of enslaved people within the public administration of the economy in colonial and antebellum society). ↑

- . George E. Spruill, [Untitled Advertisement], Edenton Gazette, N.C. Gen. Advertiser, Jan. 25, 1820, North Carolina Runaway Slave Notices, NC.CHO.45.18200125.3.1919, https://dlas.uncg.edu/notices/notice/1919 [https://perma.cc/53BM-7S9U]. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . See Jonathan A. Bush, Free to Enslave: The Foundations of Colonial American Slave Law, 5 Yale J.L. & Humans. 417, 417 (1993) (describing other legal scholars’ reliance on traditional legal sources, such as “cases, statutes, probate inventories, and records of debtors’ sales”). ↑

- . Id. at 419. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Frank I. Schechter, The Historical Foundations of the Law Relating to Trade-Marks 126 (1925). ↑

- . North Carolina Runaway Slaves Notices, 1750–1865, Digital Library on American Slavery, https://dlas.uncg.edu/notices/ [https://perma.cc/6T4W-EXAQ]. ↑

- . Freedom on the Move, https://database.freedomonthemove.org [https://perma.cc/Q2YF-J8F8]. ↑

- . Haunt, 7 Oxford English Dictionary (2d ed. 1989). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . 15 U.S.C. § 1127 (definition of the term “trademark”). ↑

- . See Kali Murray, Infrostructure(s): Administering Information, 71 Buff. L. Rev. 625, 628–32 (2023) (describing the interdisciplinary approach taken to fully capture information theory). ↑

- . Michael K. Buckland, Information as Thing, 42 J. Am. Soc’y for Info. Sci. 351, 351 (1991). ↑

- . Murray supra note 26. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Barton Beebe, applying semiotic theory to trademark law, identifies a trademark’s triadic form: that is, a trademark must be “a word, name, symbol, or device or any combination” (the signifier), refer to a good or service (the referent), and “‘identify and distinguish’ its referent” (the signified). Barton Beebe, The Semiotic Analysis of Trademark Law, 51 UCLA L. Rev. 621, 646 (2004) (quoting J. Thomas McCarthy, McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition § 3.1 (4th ed. 2002)). ↑

- . J. Shahar Dillbary, Getting the Word Out: The Informational Function of Trademarks, 41 Ariz. St. L.J. 991, 992–94 (2009) (emphasis omitted) (footnote omitted). ↑

- . See Akila Sankar McConnell, Making Wal-Mart Pretty: Trademarks and Aesthetic Restrictions on Big-Box Retailers, 53 Duke L.J. 1537, 1550–55 (2004) (examining the application of 15 U.S.C. § 1121(b), which prohibits municipal regulation of signs, and how courts have applied it to retail spaces). ↑

- . Murray, supra note 26, at 645–46 (discussing the major functions of materialization). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Mark A. Lemley & Mark P. McKenna, Trademark Spaces and Trademark Law’s Secret Step Zero, 75 Stan. L. Rev. 1, 7 (2023). ↑

- . Schechter, supra note 20, at 16. ↑

- . Murray, supra note 26, at 653. ↑

- . Id. My understanding of “sociality” is an interdisciplinary approach that draws on two discrete subfields. First, as discussed in more detail elsewhere, I draw on information technologists such as Paul Duguid and John Seely Brown and information historians such as Robert Darnton who have examined how asocial actors interacted with the early modern institutions associated with print objects. For examples of such examinations, see generally John Seely Brown & Paul Duguid, The Social Life of Information (2000), and Robert Darnton, A Literary Tour de France: The World of Books on the Eve of the French Revolution (2018). Second, I view sociality within the context of the work of Jürgen Habermas, who understands the development of political sociality through discursive publics. See Murray, supra note 26, at 634, 653–54 (discussing how information systems rely on sociality to produce a constitutive relationship between the government and regulated entities); Kali Murray, Justifying the Public Law of Patents, in Improving Intellectual Property: A Global Project 437, 442 (Susy Frankel, Margaret Chon, Graeme B. Dinwoodie, Barbara Lauriat, Jens Schovsbo eds., 2023) (“[P]olitics as publics . . . claims that the discourse over regulatory decision-making builds institutional legitimation.”); see also Aoun, supra note 1, at 599–601 (discussing discursive publics within debates over racism and trademarks). ↑

- . Neil Fligstein & Luke Dauter, The Sociology of Markets, 33 Ann. Rev. Socio. 105, 106 n.1 (2007); see also Neil Fligstein, Markets as Politics: A Political‐Cultural Approach to Market Institutions, in Readings in Economic Sociology 197, 202–04 (Nicole Woolsey Biggart ed., 2002) (examining the social actions that inform the political economy of markets). ↑

- . Laura Heymann outlines the three naming functions in trademark law: (1) the denotative function, in which the trademark serves as a “shorthand” reference between parties; (2) the connotative function, in which the trademark communicates “characteristics about a person or good”; and (3) the associative function, in which the trademark “communicate[s] relationships between or among entities through a shared name.” Laura A. Heymann, Naming, Identity, and Trademark Law, 86 Ind. L.J. 381, 391–92 (2011). ↑

- . Hannah Farber, American Commercial Property Marks: Reading According to Code, and Beyond, 57 Early Am. Literature 43, 47–48 (2022). ↑

- . See Alan L. Durham, Trademarks and the Landscape of Imagination, 79 Temp. L. Rev. 1181, 1183 (2006) (examining the use of symbolic trademarks in the description of geographic markets, including in those moments when the geographic location describes a place other than where the product was manufactured or sold). For commentary about the use of the term “sake” in America, see Peter H. Kang & Brian E. Mitchell, Foreign Language Trademarks under U.S. Trademark Law, 3 J. World Intell. Prop. 373, 377–80 (2000) (outlining dispute over sake in the United States). ↑

- . Martin Bruegel, Farm, Shop, Landing: The Rise of a Market Society in the Hudson Valley, 1780–1860, at 7 (2002). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . I note in a previous work that this process is called innovative disruption. Kali Murray, Constitutional Patent Law: Principles and Institutions, 93 Neb. L. Rev. 901, 912 (2015). ↑

- . I note in a previous work that this process is called social disruption. Id. at 914; see also Anjali Vats, Temporality in a Time of Tam, or Towards a Racial Chronopolitics of Intellectual Property Law, 61 IDEA 673, 681–83 (2021) (identifying the procedural delay in trademark litigation over scandalous and disparaging marks as a type of racialized chronopolitics that undermines Indigenous claims that trademarks harm their social identities). ↑

- . For instance, David Higgins has identified two textile companies that had trademarks in textiles (including cotton) for at least 60 years or more before their trademark registration after the passage of the Trademark Act of 1875. David M. Higgins, “Forgotten Heroes and Forgotten Issues”: Business and Trademark History During the Nineteenth Century, 86 Bus. Hist. Rev. 261, 266 n.15 (2012). ↑

- . Farber, supra note 41, at 58. ↑

- . Id. at 59. ↑

- . Haunt, 7 Oxford English Dictionary (2d ed. 1989). ↑

- . Hannah Walser, Under Description: The Fugitive Slave Advertisement as Genre, 92 Am. Literature 61, 62–63 (2020) (analyzing the fugitive slave advertisement as a genre like a novel). ↑

- . A search on the Freedom on the Move database indicates a reference to the term “jail” in more than 12,000 advertisements. See search results for “jail” in Freedom on the Move, supra note 22, https://database.freedomonthemove.org/ [https://perma.cc/RQ36-HZTK]. ↑

- . See infra text accompanying notes 95–103. ↑

- . Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-making in Nineteenth-Century America 10–11 (1997); see also Edlie L. Wong, Storytelling and the Comparative Study of Atlantic Slavery and Freedom, Social Text, Dec. 2015, at 109, 113 (2015) (“[E]pistemic violence . . . [marks] the complexly imbricated archives of the Atlantic slave trade and Asian indenture; it marks the complex relational practices of silencing to which colonized and enslaved persons were subjected.”). ↑

- . See Colin Davis, États Présent, Hauntology, Spectres and Phantoms, 59 French Stud. 373, 373 (2005) (introducing hauntology as coined by Derrida). ↑

- . Id. at 376. ↑

- . See id. at 377 (explaining that the spectre exposes the reader to the quality of unknowing within the text). ↑

- . Id. at 376. ↑

- . Id. at 373–74. ↑

- . Id. at 374. ↑

- . Ex parte Bushnell, 9 Ohio St. 77, 149 (1859). ↑

- . Michael A. Gomez, Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South 39 (1998). ↑

- . Id. at 5. ↑

- . Id. at 39. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Aldair Rodrigues, African Body Marks, Stereotypes and Racialization in Eighteenth-Century Brazil, 42 Slavery & Abolition 315, 322 (2021). ↑

- . Jacob Wilkins, N.Y. Gazette, Wkly. Mercury, June 24, 1776, Freedom on the Move, https://database.freedomonthemove.org/advertisements/17088ffd-527c-44fe-b33e-e67a9af1a1ab?advertisements%5Bquery%5D=%22country%20mark%22 [https://perma.cc/L7UG-H93M]. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . See, e.g., Higgins, supra note 47, at 263–64 (discussing how successful trademarks throughout the nineteenth century have developed into large corporations today). ↑

- . Jones T. Bryan, Twenty Dollars Reward, Raleigh Reg., N.C. Wkly. Advertiser, Feb. 10, 1801, North Carolina Runaway Slave Notices, NC.WAK.124.18010210.3.893, https://dlas.uncg.edu/notices/notice/893/ [https://perma.cc/P2S9-UJ7M]. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . See generally Roger Mellen, The Press, Paper Shortages, and Revolution in Early America, 21 Media Hist. 23 (2015) (examining the technological challenges that confronted printers in the colonial United States). ↑

- . E.g., Dennis Dawley, Thirty (Silver) Dollars Reward, State Gazette N.C., Jan. 29, 1789, North Carolina Runaway Slave Notices, NC.CRA.141.17890129.3.1262, https://dlas.uncg .edu/notices/notice/1262/ [https://perma.cc/X2X5-QR3V]. This stylized image depicted a figure walking in front of a tree with a staff in the hand. ↑

- . William Bennett, Five Pounds Reward, State Gazette N.C., June 25, 1789, North Carolina Runaway Slave Notices, NC.CRA.141.17890625.3.1052, https://dlas.uncg.edu/ notices/notice/1052/ [https://perma.cc/PCL3-FNRJ]. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . W.H. Edwards, $75 Reward, Roanoke Advoc., Apr. 1, 1830, North Carolina Runaway Slave Notices, NC.HAL.126.18300401.3.354, available at https://dlas.uncg.edu/notices/notice/354/ [https://perma.cc/7KEX-8UVT]. ↑

- . Marcus Wood, Blind Memory: Visual Representations of Slavery in England and America, 1780–1865, at 92 (2000); see also Sarah Blackwood, Fugitive Obscura: Runaway Slave Portraiture and Early Photographic Technology, 81 Am. Literature 93, 100–01 (2009) (discussing Wood’s observations on the stylizing of fugitive slave advertisements). ↑

- . See 15 U.S.C. § 1127 (defining the term “service mark” in the Lanham Act). ↑

- . Kali Murray, Intellectual Property Liberation: An Essay (Revised), 18 U. Saint Thomas L.J. 546, 550, 552 (2022). ↑

- . Search results for “brand”, Freedom on the Move, https://database .freedomonthemove.org [https://perma.cc/F6K5-M2H7]. ↑

- . Johnson and Wylly, Ga. Gazette, Aug. 15, 1764, Freedom on the Move, https://database.freedomonthemove.org/advertisements/1c5a4adb-879c-4010-8ec8-c358ee8e7f87 [https://perma.cc/P6EV-H8HU]. ↑

- . George M’kenzie, St. Gazette N.C., Feb. 20, 1794, Freedom on the Move, https://database.freedomonthemove.org/advertisements/bff948bf-5056-47e2-93b5-a5dc7c01b09e? advertisements%5Bquery%5D=branded%20on%20the%20shoulders%20in%20the%20West%20Indies%20 [https://perma.cc/6CRL-F256]. ↑

- . Josiah Pendarvis, City Gazette, Aug. 28, 1793, Freedom on the Move, https://database.freedomonthemove.org/advertisements/36d689c6-7b6d-43f7-a349-c85e0ddf36b5 ?advertisements%5Bquery%5D=brand%20on%20her%20breast%20in%20the%20form%20of%20U.”%20%20%20 [https://perma.cc/N64N-WCJV]. ↑

- . Cattle, Horses, & Other Stock Act, §§ 1–3, Digest of the Laws of the State of Alabama 79–80 (1833). ↑

- . Id. § 1, at 79. Hannah Farber also describes the same type of sponsorship relationship in the marking of hogshead barrels. See Farber, supra note 41, at 50–51 (describing the marking requirements for barrels in Virginia in order to indicate who was responsible for creating them). ↑

- . Cattle, Horses, & Other Stock Act, § 2, Digest of the Laws of the State of Alabama 80 (1833). ↑

- . Id. § 3, at 80. ↑

- . See, e.g., Strays, Stock, Droves, Party-Fences, Enclosures, Water-craft, Etc. Act, ch. 12, art. 1, §§ 15–17, Code of Mississippi 276–77 (1848) (containing statutes discussing recording brands, brand disputes, and disallowing slaves and Indians from branding stock). ↑

- . Brazil was the last country in the Western Hemisphere to eliminate slavery. Forced Labour in Brazil: 120 Years After the Abolition of Slavery, the Fight Goes On, Int’l Lab. Org. (May 13, 2008), https://www.ilo.org/resource/article/forced-labour-brazil-120-years-after-abolition-slavery-fight-goes#:~:text=On%20May%2013th%201888%2C%20Brazil,in%20this%20South% 20American%20country [https://perma.cc/2LBQ-Y436]. ↑

- . Strays, Stock, Droves, Party-Fences, Enclosures, Water-craft, Etc. Act, ch. 12, art. 1, §§ 15–17, Code of Mississippi 276–77 (1848). ↑

- . See Mark P. McKenna, Property and Equity in Trademark Law, 23 Marq. Intell. Prop. L. Rev. 117, 120 (2019) (outlining early trademark infringement actions in equity); César Ramirez-Montes, A Re-Examination of the Original Foundations of Anglo-American Trademark Law, 14 Marq. Intell. Prop. L. Rev. 91, 123–32 (2010) (outlining the development of early trademark theories of recovery in trademark and property law). ↑

- . Paul Duguid, Early Marks: American Trademarks Before US Trademark Law, 60 Bus. Hist. 1147, 1151–53 (2018) (examining public regulation of trademarks in California in the 1850s and 60s). ↑

- . A search on Freedom on the Move indicates a reference to the term “my property” on twenty-one advertisements. Search results for “my property”, Freedom on the Move, https://database.freedomonthemove.org/?advertisements%5Bquery%5D=%22my%20property%22 [https://perma.cc/D5JZ-D8Q6]. ↑

- . Alfred Brophy, The World Made by Laws and the Laws Made by the World of the Old South, in Signposts: New Directions in Southern Legal History 219, 221 (2012) (identifying historical work that centers Southern jurists as intellectuals during the antebellum era). ↑

- . Rebecca Houze, New Mythologies in Design and Culture: Reading Signs and Symbols in the Visual Landscape 1 (2016). ↑

- . See William McGeveran, Selfmarks, 56 HOUS. L. REV. 333, 333 (2018) (defining “selfmarks” as “branded personal identifiers that can be protected as trademarks” and analyzing how trademark law has evolved with these selfmarks). ↑

- . Murray, supra note 82, at 552. ↑

- . Katrina H.B. Keefer, Marked by Fire: Brands, Slavery and Identity, 40 Slavery & Abolition 659, 660 (2019). ↑

- . Id. at 664. ↑

- . Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393, 407 (1856). ↑